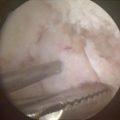

Fig. 17.1

True anteroposterior (AP) (Grashey) X-ray demonstrating preservation of the glenohumeral joint space without evidence of arthrosis

Fig. 17.2

Axillary radiograph demonstrating the glenohumeral joint is located

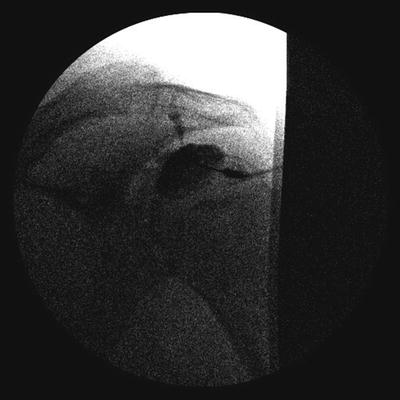

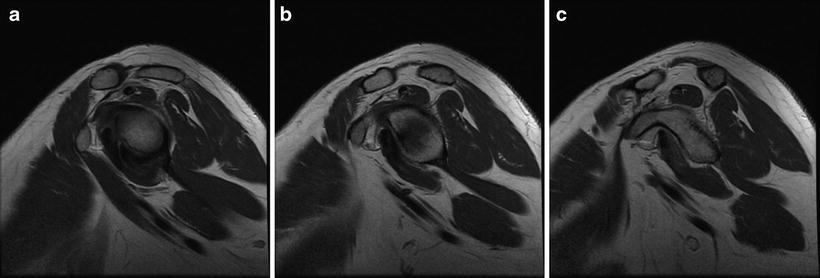

An MRI was also available for review, having been ordered by the patient’s primary care physician. MRI of the left shoulder was performed in the axial plane and in the long and short axes of the supraspinatus muscle and tendon with spin density technique without and with fat suppression as well as T1-weighted and T2-weighted techniques. Sequential T2 fat-saturated BLADE coronal oblique images are shown in Fig. 17.3a–c.

Fig. 17.3

(a–c) Sequential T2 fat-saturated BLADE coronal oblique images demonstrating significant thickening and loss of definition of the inferior capsule

MRI findings are subtle in frozen shoulder. To be certain, frozen shoulder is a clinical diagnosis, and there are no specific direct signs that are pathognomonic for frozen shoulder. Described direct signs suggestive of frozen shoulder include:

Thickening of the glenohumeral joint capsule along the axillary pouch

Thickening of the coracohumeral ligament

Obliteration of the subcoracoid fat triangle

Rotator interval synovitis

In the present patient, Fig. 17.3a–c demonstrates significant thickening and loss of definition of the inferior capsule. The supraspinatus tendon has mild thinning and increased signal consistent with tendinosis.

Management

Given the patient’s symptoms of insidious onset of pain and a physical examination where active and passive range of motion were equal, a clinical diagnosis of frozen shoulder was established. Radiographs failed to demonstrate arthritic change to account for the loss of motion, and there was no evidence of posterior shoulder dislocation. As such, the diagnosis was confirmed. Findings at MRI failed to demonstrate a secondary cause for frozen shoulder, such as concomitant rotator cuff tear. The decision was made to proceed with nonoperative management.

The patient was sent for supervised physical therapy with a structured home exercise program. An evidence-based program of pendulum circumduction, combined with passive shoulder stretching exercises in forward elevation, external rotation, horizontal adduction, and internal rotation, was initiated. An overhead pulley was supplied, and the home exercise program performed five times daily.

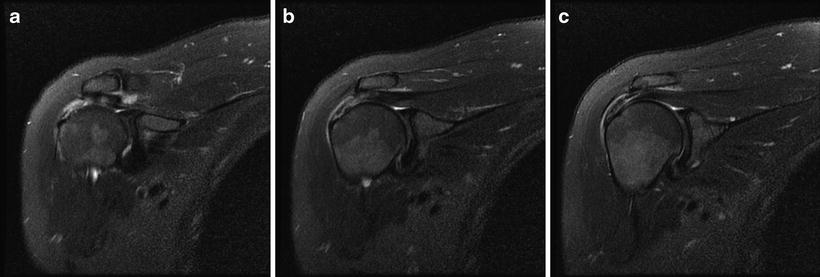

The patient returned 6 weeks later with little improvement. Range of motion had increased by only 5–10° in each plane of motion. The pain was slightly diminished. At that juncture, the decision was made to proceed with intra-articular glenohumeral corticosteroid injection. Given the significant capsular contraction and thickening, we prefer not to inject patients in the office. Rather, intra-articular injection achieved via arthrographic confirmation is our recommended technique. As demonstrated in Fig. 17.4, there is a complete lack of capsular filling, particularly in the inferior axillary recess.

Fig. 17.4

Fluoroscopic image from image-guided glenohumeral corticosteroid injection. There is a complete lack of capsular filling, particularly in the inferior axillary recess

The patient returned to the orthopedic clinic approximately 5 weeks later and had near complete resolution of his pain. His forward elevation was now 140°, and passive external rotation was 45°. At 3 months post-injection, he had complete resolution of his symptoms with full range of motion.

Discussion

Nonspecific findings of MRI for frozen shoulder

Nonoperative management of frozen shoulder

Case 2

A 54-year-old right-hand dominant woman presented to the orthopedic clinic with a 3-month history of right shoulder pain. Her pain began suddenly after a ground level mechanical fall onto her right side. Since that time, she has had progressively worsening shoulder pain that has particularly bothered her at night. However, over the last 3 weeks, she states that her pain has somewhat abated. She has taken an over-the-counter anti-inflammatory with some relief. She has not done any physical therapy. Her previous medical history is notable for hypothyroidism for which she takes levothyroxine. She has seen a different orthopedic surgeon who referred her after obtaining an MRI.

On physical examination, she is well and in no obvious distress. Examination of the cervical spine does not reveal any pathologic findings. General inspection is normal. Palpation reveals tenderness over the greater tuberosity. Evaluation of range of motion demonstrates 80° of forward elevation both actively and passively, 0° of active and passive external rotation, and 35° of pure passive abduction. Manual muscle strength testing reveals 4+/5 supraspinatus strength and 5/5 internal and external rotation strength. Neer and Hawkins signs are unable to be elicited secondary to lack of motion.

Imaging

A standard radiographic series was obtained, and this demonstrated a preserved glenohumeral joint space without evidence of arthrosis. There was no evidence of posterior glenohumeral dislocation.

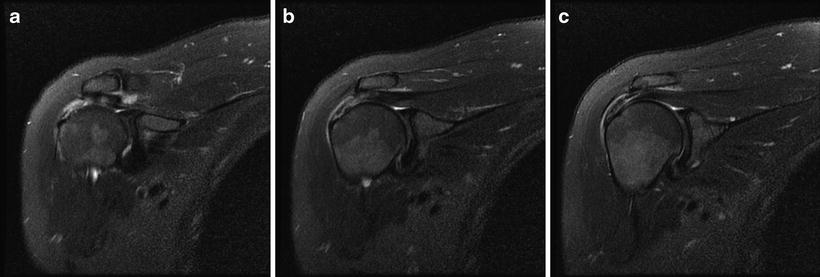

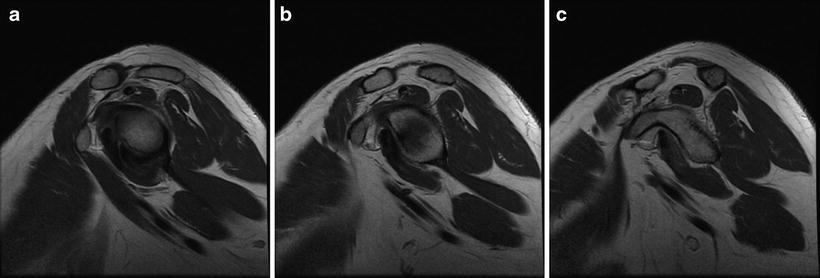

Standard MRI sequences without contrast arthrography were obtained. Proton density (PD) (intermediate-weighted) fat-suppressed coronal oblique images are shown in Fig. 17.5a–c. Proton density (intermediate-weighted) sagittal oblique images are shown in Fig. 17.6a–c. Figure 17.5a–c demonstrates the anterior aspect of the supraspinatus tendinous insertion into the greater tuberosity. There is severe tendinopathy at the insertion with suggestion of a full-thickness tear of approximately 13 mm anterior-to-posterior and 10 mm medial-to-lateral. There was no evidence of fatty atrophy of the supraspinatus muscle belly. On sagittal oblique imaging shown in Fig. 17.6a–c, there is partial obliteration of the subcoracoid fat triangle. The subcoracoid fat triangle is a radiologic space defined anterosuperiorly by the coracoid process, superiorly by the coracohumeral ligament, and posteroinferiorly by the joint capsule. Partial or complete obliteration of this fat triangle is highly suggestive of adhesive capsulitis.

Fig. 17.5

(a–c) Sequential proton density (PD) (intermediate-weighted) fat-suppressed coronal oblique images demonstrating severe tendinopathy suggestive of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear

Fig. 17.6

(a–c) Sequential proton density (intermediate-weighted) sagittal oblique demonstrating partial obliteration of the subcoracoid fat triangle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree