6 Gallbladder

Organ Boundaries

Organ Boundaries

KEY POINT

The aorta and splenic vein provide landmarks for identifying the pancreas.

LEARNING GOALS

Locate the gallbladder.

Locate the gallbladder.

Define the gallbladder in its entirety.

Define the gallbladder in its entirety.

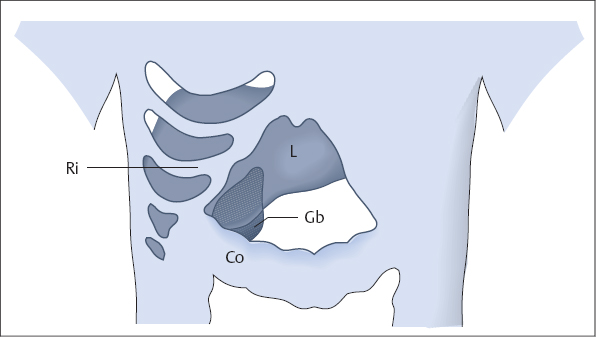

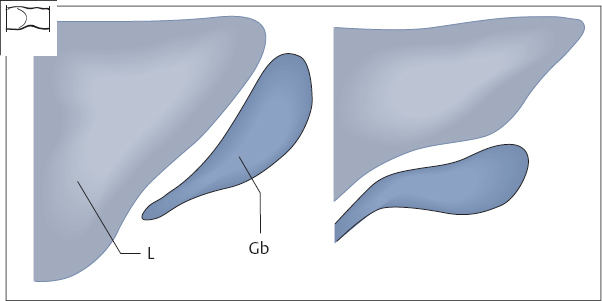

The gallbladder lies beneath the right costal arch, where it is covered mainly by the liver. Just caudal to it are the transverse colon and right colic flexure. These three structures—the liver, costal arch, and colon—form the anatomical framework within which the gallbladder is scanned. The liver is used as an acoustic window, while the colon and costal margin act as barriers. The acoustic windows that are available for scanning the gallbladder are relatively narrow (Figs. 6.1, 6.2).

Fig. 6.1 Anterior approach to the gallbladder (Gb). The colon (Co) and ribs (Ri) are barriers to scanning, while the liver (L) provides an acoustic window.

Fig. 6.2 Lateral approach to the gallbladder. Again, the colon (Co) and costal arch are barriers while the liver provides an acoustic window.

Locating the gallbladder

Barriers to scanning

Every beginner has difficulty locating the gallbladder. Beside lack of experience, there are patient-related factors that can make the gallbladder difficult to find.

The gallbladder has a small cross section.

The gallbladder has a small cross section.

It may be hidden by bowel gas.

It may be hidden by bowel gas.

It may be contracted.

It may be contracted.

It lies behind the costal margin.

It lies behind the costal margin.

Optimizing the scanning conditions

KEY POINT

The sonographic characteristics of the gallbladder are: smooth margins, absence of internal echoes, and posterior acoustic enhancement.

The gallbladder is examined in the fasted patient. This includes abstinence from coffee and nicotine (which stimulate contraction). As in the liver, scanning conditions are improved by having the patient raise the right arm above the head. It is also helpful to scan at full inspiration.

Organ identification

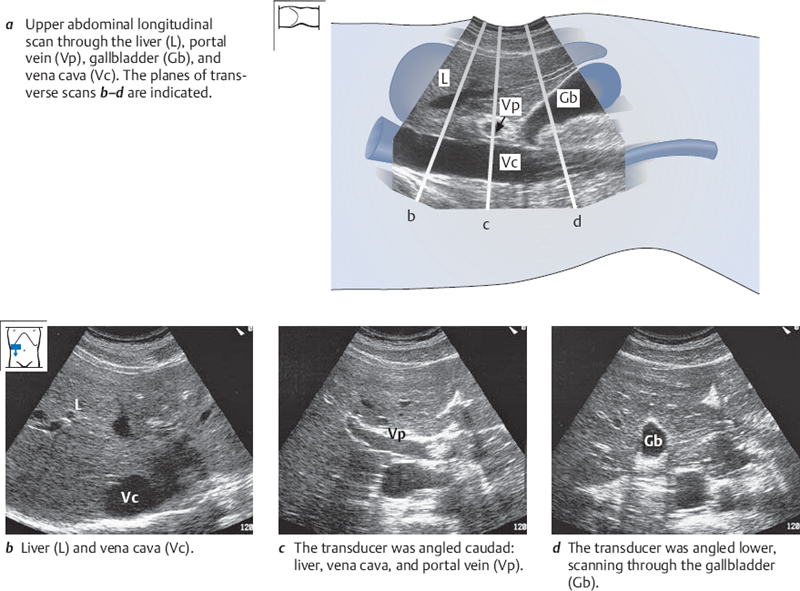

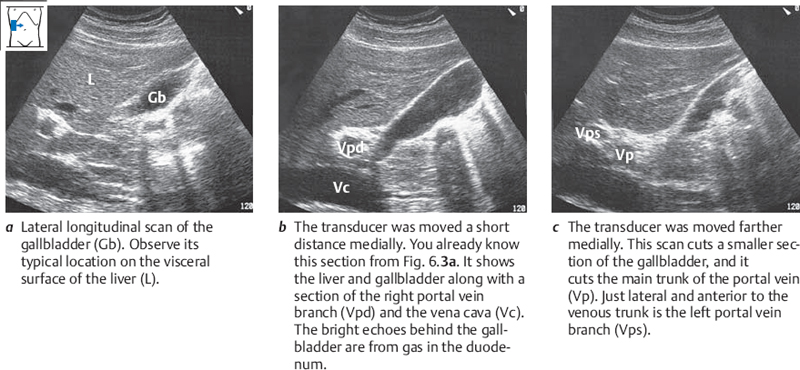

Place the probe transversely on the right costal arch, approximately at the midclavicular line. Scan up into the liver at a steep angle (Fig. 6.3b), then slowly angle the transducer downward. First you will see the portal vein (Fig. 6.3c). Next the gallbladder will appear as an echo-free organ with smooth margins and posterior acoustic enhancement (Fig. 6.3d). The longitudinal scan in Fig. 6.3a indicates the position of the three transverse scans in the figure.

Imaging the entire gallbladder

You will learn below how to scan the entire gallbladder systematically using parallel upper abdominal transverse scans, upper abdominal longitudinal scans, and intercostal flank scans.

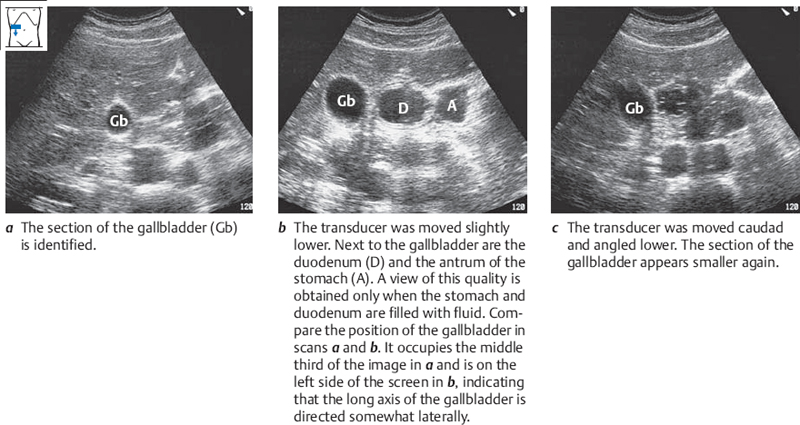

Defining the gallbladder in upper abdominal transverse scans

Image the gallbladder in an upper abdominal transverse scan, positioning it slightly to the left of the midline on the screen. Pause briefly, then scan all the way down the gallbladder in parallel transverse sections (Fig. 6.4).

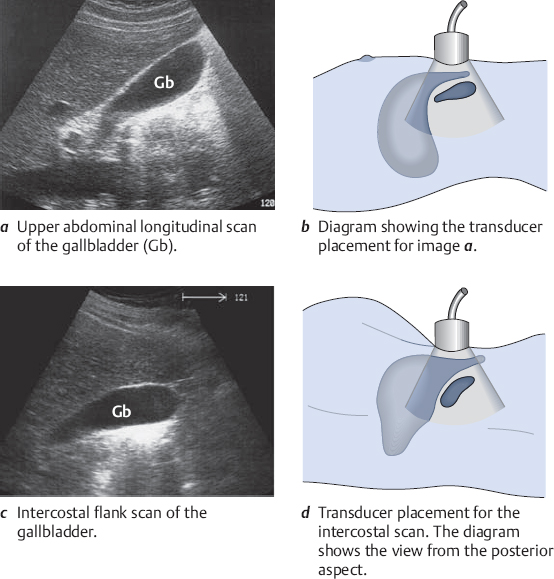

Defining the gallbladder in upper abdominal longitudinal scans

Obtain a transverse section of the gallbladder that displays its largest diameter. Then rotate the probe 90° while watching the screen. Observe how the rounded shape of the gallbladder assumes the elliptical shape of a longitudinal section (Fig. 6.5a). Move the transducer to the right in small increments until the gallbladder disappears (Fig. 6.5b,c). Scan from the right to the left side of the gallbladder.

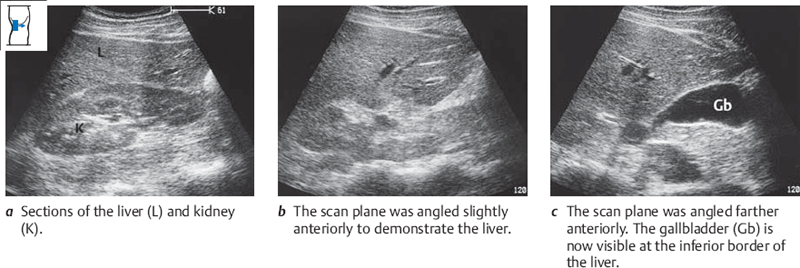

Locating and defining the gallbladder with intercostal flank scans

The third scanning approach to the gallbladder is the lateral approach through the intercostal spaces. The intercostal approach can be challenging initially, but with proper technique it can provide excellent views of the gallbladder.

Place the transducer in a lower intercostal space at the midaxillary line. Direct the beam between the ribs, and define a caudal section of the liver. Sweep the scan from posterior to anterior in a fan-shaped pattern. If necessary, move the transducer to a more anterior intercostal space and repeat the scan. Figure 6.6c illustrates a typical intercostal view of the gallbladder.

The image in Fig. 6.6c requires some explanation. The view obtained with an intercostal flank scan is somewhat similar to an upper abdominal longitudinal scan. Figure 6.7 shows how the viewing angles differ.

Variable position of the gallbladder

In typical cases the long axis of the gallbladder is directed laterally downward at an oblique angle. But it may also follow the long axis of the body, and occasionally it runs somewhat medially (Fig. 6.8).

The fundus of the gallbladder is usually located anteriorly, lying directly upon the inferior border of the liver (Fig. 6.9). In other cases it is located deep beneath the liver.

Fig. 6.9 Position of the gallbladder fundus in relation to the inferior hepatic border.

L = liver, Gb = gallbladder.

Nonvisualization of the gallbladder

There can be many reasons why the gallbladder is not seen with ultrasound. The most common reason for beginners is a simple lack of experience. The illustrations in this book were taken from cases with favorable scanning conditions, but the actual practice of gallbladder scanning can be more difficult. The most common examiner-independent causes of poor gallbladder visualization are listed in Table 6.1.

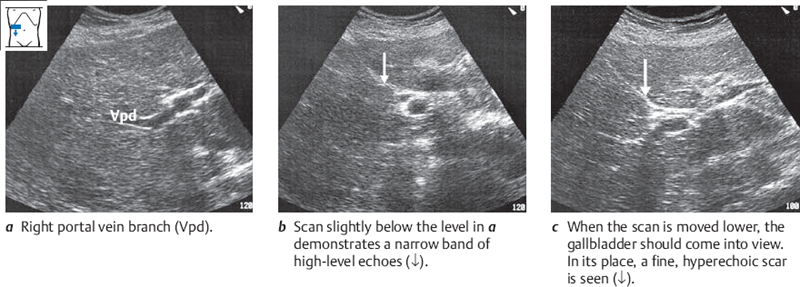

Prior cholecystectomy. Naturally, the gallbladder is not found in patients who have had a cholecystectomy. Elderly patients may have forgotten the operation, and subtle scars are easily overlooked in the dark examination room. You should specifically look for a cholecystectomy scar if the gallbladder is not found and the patient is unsure about his or her surgical history. If the organ has been removed, a very echogenic scar can usually be found in the gallbladder bed.

In obese patients, a limited assessment of the gallbladder can be made by scanning from the flank and using the liver as an acoustic window.

Even coffee or nicotine can cause the gallbladder to contract.

The series of images in Fig. 6.10 illustrate a systematic search for the gallbladder or cholecystectomy scar, analogous to Fig. 6.3.

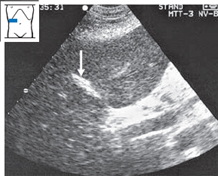

The width of a cholecystectomy scar is highly variable (Fig. 6.11).

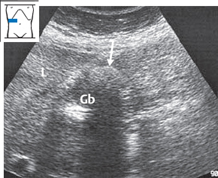

Obesity. Marked obesity can make it very difficult to visualize the gallbladder in subcostal scans (Fig. 6.12). Limited views of the gallbladder can often be obtained in these cases with flank scans using the liver as an acoustic window.

Postprandial contraction. After meals the gallbladder may contract to the size of the portal vein lumen. When asking the patient whether he or she has eaten, remember that coffee or nicotine use can also cause the gallbladder to contract (Fig. 6.13).

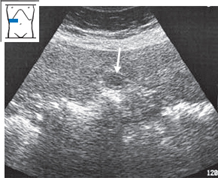

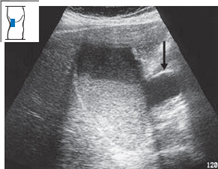

Fig. 6.11 Previous cholecystectomy. Scan demonstrates a bright, rhomboid-shaped scar in the former gallbladder bed (↓).

Fig. 6.12 Obesity and gallstones. The liver contours are indistinct, and the gallbladder wall is poorly demarcated from the outline of the liver (L). The gallbladder shows a small residual lumen with a stone (↓). Gb = gallbladder.

Shrunken gallbladder. The gallbladder may shrink from chronic inflammation. The bile becomes viscid and sludge or gallstones may form, causing loss of the fluid-filled lumen. It can be very difficult in these cases to delineate the gallbladder from the duodenum (Figs. 6.14–6.16).

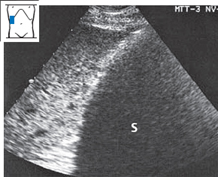

Fig. 6.14 Gallstones. The gallbladder is completely filled with stones, which cast a large, uniform acoustic shadow (S). The gallbladder lumen is not visualized.

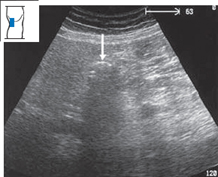

Fig. 6.15 Shrunken gallbladder. The gallbladder lumen is obliterated by small stones and debris (↓). The gallbladder is poorly delineated from surrounding structures.

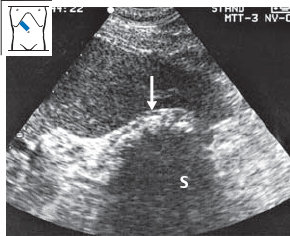

Fig. 6.16 Shrunken gallbladder. The gallbladder lumen is obliterated by stones and debris (↓), which cast a dense acoustic shadow (S).

Organ Details

Organ Details

KEY POINTS

The normal gallbladder is 9–11 cm in length. The normal transverse width is 4 cm or less.

Gallbladder volume = length × width × depth × 0.5 cm.

LEARNING GOALS

Identify the gallbladder regions in the sonogram.

Identify the gallbladder regions in the sonogram.

Determine the dimensions of the gallbladder.

Determine the dimensions of the gallbladder.

Evaluate the gallbladder wall.

Evaluate the gallbladder wall.

Evaluate the gallbladder contents.

Evaluate the gallbladder contents.

Recognize artifacts in gallbladder scanning.

Recognize artifacts in gallbladder scanning.

Regions of the gallbladder

The gallbladder consists of a fundus, body, neck, and infundibulum.

Sonographic identification of the gallbladder regions

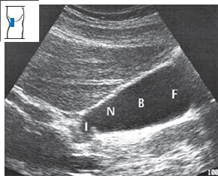

Image the gallbladder in longitudinal section. Try to obtain an optimum view of the gallbladder regions in one image, and study that view (Fig. 6.17).

Size of the gallbladder

Reports of normal gallbladder size vary because the dimensions of the organ are highly variable. The gallbladder may be up to 12 cm in length. Most authors state a range of 9–11 cm for gallbladder length, with a transverse diameter up to 4 cm.

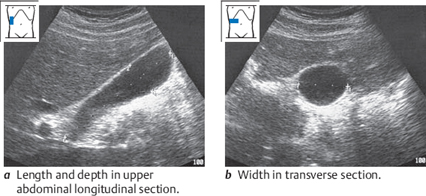

Sonographic determination of gallbladder size

The length and depth of the gallbladder are measured in an upper abdominal longitudinal scan, and the width is measured in a transverse scan. The volume of the gallbladder is then calculated using a simplified formula: length (cm) × width (cm) × depth (cm) × 0.5 (Fig. 6.18).

Enlargement of the gallbladder

Large gallbladders can occur as morphologic variants (Figs. 6.19, 6.20), especially in older patients and diabetics. Prolonged fasting also leads to a large gallbladder that may contain sludge.

If the transverse diameter of the gallbladder exceeds 4 cm, a pathologic condition should be suspected.

A normally distended gallbladder is distinguished from a hydropic gallbladder by its relatively lax appearance. In hydrops, the gallbladder is markedly distended due to an outflow obstruction, usually caused by a cystic or common duct stone (Fig. 6.21). The normal gallbladder is comparable to a water-filled balloon that is not under pressure, whereas the hydropic gallbladder is like a balloon that has been tightly inflated with an equal volume of air.

Table 6.2 reviews the causes of a large gallbladder.

| Morphologic variant |

| Fasting |

| Atony (diabetes mellitus) |

| Advanced age |

| Hydrops |

| Empyema |

Fig. 6.20 Enlargement of the gallbladder due to obstructed outflow by a carcinoma of the pancreatic head.

Fig. 6.21 Distended gallbladder filled with sediment in a patient with pancreatic head carcinoma. The distended CHD (↓) is also visible.

Variable shape of the gallbladder

The assessment of gallbladder shape is more useful than measuring its dimensions. With practice, you will gain an appreciation of the variability of normal gallbladder shapes. Frequently the gallbladder is pear-shaped (Fig. 6.22a). It may also be round, elongated, or angulated (Fig. 6.22b,c

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree