Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

- ◼

The stomach is anatomically subdivided into the cardia, fundus, body, and antrum, with inflow regulated by the lower esophageal sphincter and outflow by the pyloric sphincter.

- ◼

The incisura angularis represents the acute angle formed on the lesser curvature, which marks the transition from body to antrum.

- ◼

- ◼

The gastric wall is composed of four layers: the mucosa (containing the epithelium and lamina propria), the submucosa (containing vascular, lymphoid, and nervous tissue), the trilaminar muscularis externa, and the serosa.

- ◼

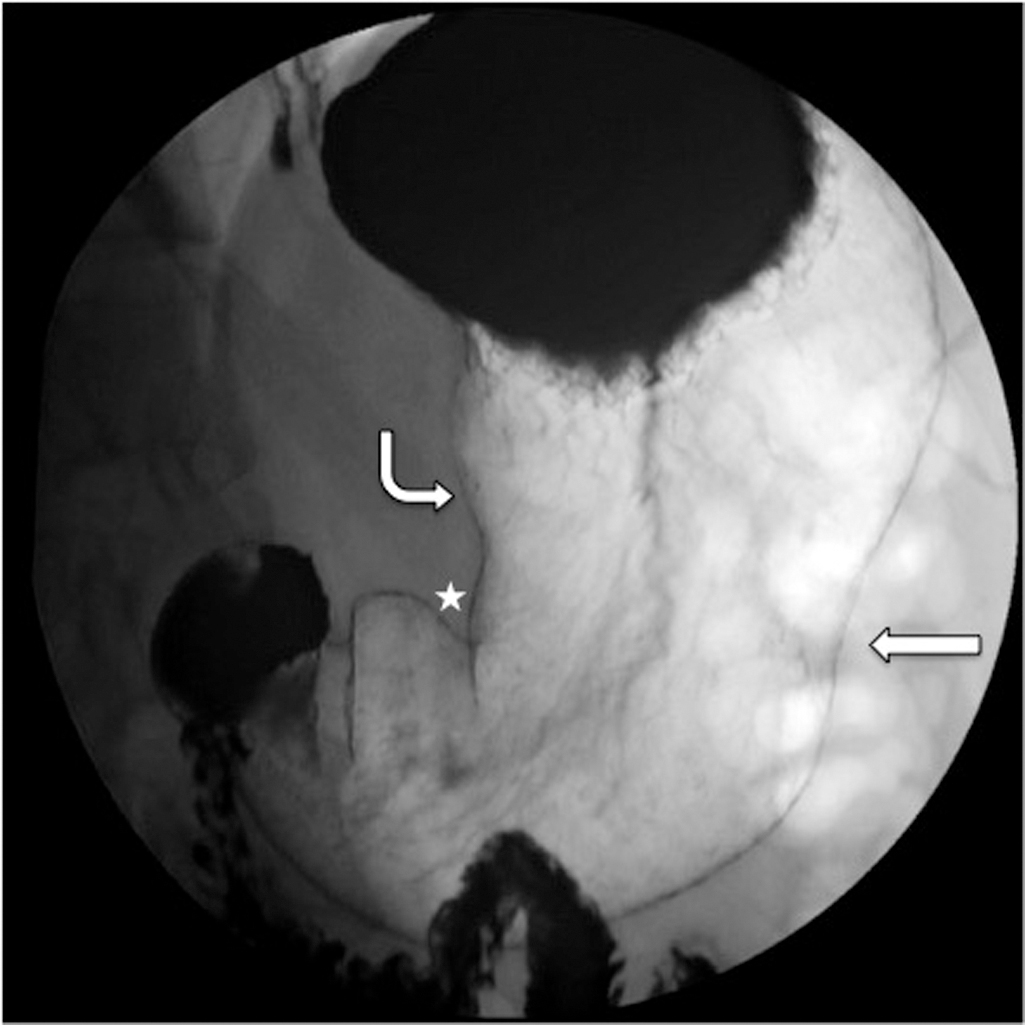

The areae gastricae represent the normal reticular mucosal pattern in a well-distended stomach, with rugal folds becoming more prominent in a nondistended stomach ( Fig. 3.1 ).

Fig. 3.1

Areae gastricae representing a normal mucosal pattern.

- ◼

It is bounded by the lesser omentum attached along the lesser curvature, and greater omentum attached to the greater curvature.

- ◼

The right and left gastric arteries supply blood to the lesser curvature, whereas the gastroepiploic and short gastric arteries supply the greater curvature and fundus, respectively.

- ◼

Venous drainage is provided by the gastric veins that drain into the portal vein, the short gastric and left gastroepiploic veins that drain into the splenic vein, and right gastroepiploic vein that drains into the superior mesenteric vein.

- ◼

Techniques

Fluoroscopy

- ◼

Even in the modern age of fast and accessible cross-sectional imaging, fluoroscopy has remained a prominent modality for assessing the stomach because of its superior spatial resolution and dynamic nature.

- ◼

Double contrast technique: preferred method for evaluation of the gastric mucosa. The patient is given effervescent granules to distend the stomach followed by a barium suspension to coat the mucosa.

- ◼

Single contrast technique: less commonly performed, but useful for assessment of peristalsis, gastric outlet obstruction, postoperative patients, or suspected perforation.

Computed tomography

- ◼

Better for depiction of extraluminal disease and associated complications.

- ◼

May use water or positive oral contrast.

Protocols

Fluoroscopy

- ◼

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) double contrast technique:

- ◼

To obtain adequate distension of the stomach, the patient should be given a dose of effervescent crystals at the start of the examination. Instruct the patient to resist belching.

- ◼

Most evaluations of the stomach are preceded by upright imaging of the esophagus with a thick barium solution. When completed, the patient should be lowered into the supine position, as to retain barium within the dependent fundus.

- ◼

The patient should then complete a 540 degree rotation to the left to coat all surfaces of the stomach, with final right anterior oblique (RAO) positioning.

- ◼

Image the contrast opacified duodenal bulb as barium exits the stomach.

- ◼

Rotate the patient into the right posterior oblique (RPO) position to obtain views of the anterior and posterior walls of the stomach.

- ◼

Rotate the patient into the supine position to obtain images of the lesser and greater curvatures ( Fig. 3.2 ).

Fig. 3.2

Anterior-posterior view of the stomach demonstrating the greater ( arrow ) and lesser ( curved arrow ) curvatures. The incisura angularis is seen along the lesser curvature ( asterisk ).

- ◼

Rotate the patient into the left posterior oblique (LPO) position to obtain air-contrast images of the antrum and duodenal bulb.

- ◼

If further images of the esophagus are required in the prone position, these should be obtained at this time, followed by assessment for reflux, and a full field of view image of the opacified bowel.

- ◼

- ◼

Upper GI single contrast technique:

- ◼

If there is question of GI leak, the examination should first be performed with water-soluble contrast before proceeding to barium.

- ◼

Obtain a scout image of the abdomen to assess for free air. In postoperative patients, scout imaging also serves as a baseline comparison.

- ◼

Using thin barium, first obtain upright views of the esophagus in the LPO position. The patient should drink enough to fill the stomach.

- ◼

Obtain upright views of the gastric body and antrum in the LPO, anteroposterior (AP), and RPO positions. Use compression when possible.

- ◼

Bring the table to the horizontal position and take an image of the fundus in the supine position. As the fundus is often positioned beneath the ribcage, it cannot be compressed.

- ◼

Image the contrast-filled antrum and duodenal bulb in the RAO position. Compression may be performed from underneath.

- ◼

Finish by obtaining an overhead film of the stomach and small bowel.

- ◼

- ◼

The aforementioned protocols are only to serve as a guide. Evaluation of gastric pathology requires prompt identification and real-time adjustment to obtain the best images possible while limiting radiation exposure.

Specific disease processes

Benign versus malignant ulcers

Fluoroscopy

- ◼

Benign ulcers (95%):

- ◼

Pooling of barium within a smooth, sharply defined mucosal defect that projects beyond the stomach contour.

- ◼

Radiating folds reach the edge of the ulcer ( Fig. 3.3 ).

Fig. 3.3

Benign ulcer with smooth borders and radiating folds reaching the ulcer edge ( arrows ).

- ◼

More common on lesser curvature, antrum, and posterior wall.

- ◼

Giant ulcers over 3 cm are almost always benign.

- ◼

Hampton line: Thin radiolucent line between the gastric lumen and the ulcer seen on profile view representing a layer of mucosa overhanging the ulcer edge.

- ◼

- ◼

Malignant ulcers (5%):

- ◼

Irregular shape not extending beyond the stomach contour.

- ◼

Asymmetric radiating folds that do not reach the ulcer’s edge.

- ◼

More common on greater curvature.

- ◼

Carmen Meniscus sign: Radiolucent raised border convex toward the lumen surrounding the ulcer on profile view.

- ◼

Computed tomography

- ◼

Used to assess for complications, such as perforation, involvement of surrounding structures, and metastases.

- ◼

Depicts wall thickening, submucosal edema, and luminal narrowing.

Focal masses

Polyps

- ◼

Hyperplastic:

- ◼

Most common benign epithelial neoplasm of the stomach.

- ◼

Seen with chronic gastritis, no malignant potential.

- ◼

More likely in fundus or body.

- ◼

Smooth, sessile or pedunculated, smaller than 1 cm.

- ◼

- ◼

Hamartomatous:

- ◼

Peutz-Jeghers and Cronkhite-Canada syndromes.

- ◼

No malignant potential.

- ◼

Clustered broad-based polyps.

- ◼

- ◼

Adenomatous:

- ◼

Increased risk of malignancy, although higher risk of coexisting gastric cancer than of malignant transformation.

- ◼

Familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome.

- ◼

More likely in antrum and body.

- ◼

Single, lobulated or cauliflower-like, over 1 to 2 cm.

- ◼

- ◼

Fluoroscopy:

- ◼

Seen as radiolucent filing defects if dependent.

- ◼

Rim of barium creating ringed shadows if nondependent ( Fig. 3.4 ).

- ◼