Introduction

Imaging Techniques and Anatomy

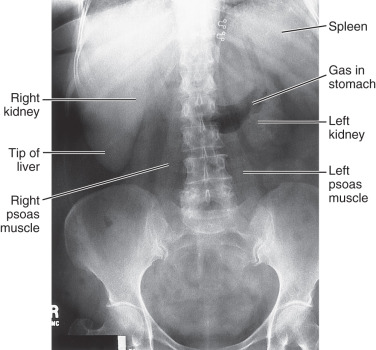

The most common imaging study of the abdomen is referred to as a KUB, or plain image of the abdomen. The term KUB is historical nonsense. It stands for k idney, u reter, and b ladder, none of which is usually seen on a regular x-ray of the abdomen; nevertheless, the term remains widely used. A KUB is usually done with the patient supine ( Fig. 6.1 ). When examining this image, you should look at the bony structures, the lung bases, and then the soft tissue and gas patterns ( Box 6.1 ). The soft tissue pattern analysis should include evaluation of the lateral psoas margins. Whether you see them bilaterally, only faintly, or throughout their length depends on the shape of the psoas and the amount of retroperitoneal fat in that individual. It is all right if you do not see the psoas margin on either side. If you see the psoas margin on one side but not on the other, this is most commonly due to normal anatomic variation. In about 25% of cases, however, pathology will be found on the side of the obscured psoas margin.

Even though they are difficult to see, you should look for the outlines of the kidneys. Again, if you cannot see the outlines, you should not be terribly concerned, because they are often obscured by overlying bowel gas and fecal material. The liver is seen as a homogeneous soft tissue density in the right upper quadrant. The spleen can sometimes be seen as a smaller homogeneous density in the left upper quadrant. Although you will be able to appreciate massive enlargement of either one of these organs, minimal to moderate enlargement is very difficult to ascertain, and you should think twice before you suggest it. Clinical palpation and percussion are at least as accurate as x-rays in this situation.

Evaluation of the gas pattern also is important ( Box 6.2 ). Because people routinely swallow air and drink lots of carbonated beverages, the stomach almost always has some gas in it. When a person is lying on his or her back, the air will go to the most anterior portion of the stomach, which is the body and antrum. This is seen as a curvilinear air collection, just along the left side of the upper lumbar spine ( Fig. 6.2 ). If the person has swallowed a lot of air, you may see gas bubbles within the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract, extending from the stomach to the rectum. The origin of almost all these bubbles is swallowed air and not gas produced by intestinal bacteria. You should be able to identify the air patterns in the stomach, small bowel, colon, sigmoid, and rectum. Gas in the small bowel usually can be identified because small bowel mucosa has extremely fine lines that cross all the way across the lumen. Most small bowel gas is located in the left midabdomen and the lower central abdomen. The colon often can be traced from the cecum in the right lower quadrant to both the hepatic and splenic flexures and down to the sigmoid. The cecum and the colon often have a bubbly appearance, representing a mixture of gas and fecal material. Colonic air often has a somewhat cloverleaf-shaped appearance caused by the haustra of the colon. The normal small bowel diameter should not exceed 3 cm, and the colon should not exceed 6 cm. The cecum can normally be somewhat larger than the rest of the colon and may be up to 8 cm in diameter.

Collections Normally Present

Look for dilatation of structure and assessment of wall or mucosal thickness in stomach, small bowel, colon, and rectosigmoid

Collections Not Normally Present

Free air under the diaphragm (upright image)

Free air on supine radiograph (double bowel wall sign)

Right upper quadrant: portal vein (peripheral in liver), biliary system (central in liver)

Small bubbles in an abscess

Emphysematous cholecystitis, pyelonephritis, or cystitis

In addition to a supine abdominal image, a three-way view of the abdomen is often obtained. The additional two views are an upright posteroanterior (PA) chest x-ray and a view of the abdomen taken with the patient standing upright. The PA view of the chest is taken to look for chest pathology that may be mimicking or causing abdominal symptoms, as well as to look for free air underneath the hemidiaphragms. The reason for the standing view of the abdomen is to look at the air-fluid levels within the bowel to differentiate between an obstruction and an ileus.

A common variant is called colonic interposition (also called Chilaiditi syndrome ). In this normal variant, the hepatic flexure of the colon can slip up between the superior aspect of the liver and the dome of the right hemidiaphragm ( Fig. 6.3 ). This should not be mistaken for free air. When colonic interposition occurs, you can almost always see the haustral markings of the colon.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the most common procedure used to image abdominal pathology. The visualization of the solid organs, peritoneum, and retroperitoneum that is obtained with CT means that CT is being ordered as much as or more than plain abdominal radiographs. CT anatomy is presented in Fig. 6.4 . With new scanners, the entire pelvis and abdomen can be imaged in a few seconds. For evaluation of the solid organs, imaging may be done with or without iodinated intravenous (IV) contrast agents. For evaluation of suspected pathology in the stomach, small intestine, colon, or rectum, the lumen can be differentiated by using orally administered contrast agents, either dilute barium or just water.

Patients commonly prepare by drinking oral contrast about 1 to 3 hours before the examination. If pelvic pathology is suspected, rectal contrast is occasionally given at the time of the examination.

With CT virtual colonoscopy, a three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the abdomen is generated, and the computer is used to create images that track the inside of the colon. This technique requires that the colon be well cleaned so that small bits of fecal material are not mistaken for polyps. True colonoscopy has the advantage that if a lesion is seen, a biopsy can be performed.

Ultrasound examination is used primarily to image the liver, kidneys, gallbladder, common bile duct, and, to a much lesser extent, pancreas and appendix. Ultrasound is often limited by the inability of the sound to penetrate air and by large loops of bowel that may obscure underlying pathology. Ascites is easily detected and localized for paracentesis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is being used more frequently than in the past for both abdominal and pelvic pathology. It tends to be more useful in adults than children and for solid organs that have little motion during the examination. As with ultrasound, there is an advantage because neither uses ionizing radiation. Often it is necessary to use IV contrast (such as gadolinium). Imaging of the bowel is often less than satisfactory.

Nuclear medicine scans provide physiologic information that is often not available using other imaging techniques. They are often used to quantitate gastroesophageal reflux and gastric emptying times, diagnose acute cholecystitis and bile leaks, determine the site of GI bleeding, and stage tumors.

Pneumoperitoneum

It is easiest to identify small amounts of free air in the peritoneal cavity by doing an upright chest x-ray. In this manner, as little as 3 or 4 mL of air may be visualized ( Fig. 6.5A ). An upright abdominal radiograph is usually not especially useful to look for free air because the domes of the diaphragms are often off the upper edge of the image. It is extremely difficult to appreciate even relatively large amounts of free air within the peritoneal cavity by looking at a supine (KUB) view of the abdomen. If a lot of free air is present, you may be able to see the bowel wall outlined by air (see Fig. 6.5B ). If the patient is too sick to stand and you suspect a small pneumoperitoneum, order a left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen. In this manner, with the patient lying on the left side (for 10–15 minutes), small amounts of air can be seen tracking up over the lateral aspect of the right lobe of the liver. Tiny amounts of free air can be detected on CT scans (see Fig. 6.5C ).

Intra-Abdominal Abscesses and Fever of Unknown Origin

Air can be seen within some, but by no means all, abscesses. Although an extremely large abscess may be appreciated on a plain radiograph, it is often difficult to tell whether you are looking at air in the bowel or in some other structure. For this reason, the imaging test of choice when an abdominal or pelvic abscess is suspected is a CT scan ( Fig. 6.6 ). It is important that under these circumstances you order a CT scan with GI contrast so that the entire bowel can be filled with contrast. If this is not done, it may be difficult, even on a CT scan, to differentiate a collection of bowel that has air and fluid in it from an abscess.

The imaging workup of a patient with a fever of unknown origin usually begins with a chest x-ray. Most infectious processes of the chest are quite obvious. Once intrathoracic pathology has been excluded, the next place to look is the abdomen and pelvis. Assuming that the physical examination of the abdomen and pelvis is negative, a CT scan is usually ordered.

Feeding Tubes

As mentioned in Chapter 3 , feeding tubes and nasogastric tubes are particularly recalcitrant medical devices. Not only can they inadvertently be passed into the trachea and major bronchus, but also they love to coil in the pharynx and stomach. On the plain radiograph, a well-placed enteric (Dobbhoff) feeding tube can be seen coming down the esophagus, passing in an arc through the stomach toward the right of midline, and then progressing downward in a reverse arc through the duodenum, back to the left, and across the vertebral column. It is best to have the tips of these feeding tubes near the junction of the duodenum and jejunum (ligament of Treitz; Fig. 6.7 ). An unacceptable position of a feeding tube tip is in the esophagus or at the gastroesophageal junction ( Fig. 6.8 ). If you feed patients with a tube in these positions, esophageal reflux and the potential for aspiration can occur.

Abdominal Calcifications

Abdominal calcifications are quite common, and you should be familiar with them so that you know which are important and which to discount ( Box 6.3 ). Fortunately, most of them have some characteristics that make this task relatively easy. Calcifications in the right upper quadrant are usually gallstones or kidney stones. If the calcifications are multiple, are close together, and lie outside the normal expected area of the kidney, you can be reasonably sure that they are gallstones ( Fig. 6.9 ). A single calcification in the right upper quadrant may be due to either a kidney stone or a gallstone. A simple way to tell the difference is to take a right posterior oblique view. A gallstone will rotate anteriorly and will not move with the outline of the kidney. Another way to tell the difference is to order a right upper quadrant ultrasound study, on which gallstones are easily identified ( Fig. 6.10 ). In addition, if the patient has right upper quadrant pain or jaundice, the ultrasound image will allow you to assess whether the common bile duct is dilated and look at the internal architecture of the liver and pancreas.

Right Upper Quadrant

Gallstones

Renal calculus, cyst, or tumor

Adrenal calcification

Right Midabdomen or Right Lower Quadrant

Ureteral calculi

Mesenteric lymph node

Appendicolith

Left Upper Quadrant

Splenic artery

Splenic cyst

Splenic histoplasmosis (multiple and small)

Renal calculus, cyst, or tumor

Adrenal calcification

Tail of pancreas

Central Abdomen

Aorta or aortic aneurysm

Pancreas (chronic pancreatitis)

Calcified metastatic nodes

Pelvis

Phleboliths (low in pelvis)

Uterine fibroids (popcorn appearance)

Dermoid

Bladder stone

Calcifications in buttocks from injections

Prostatic (behind symphysis)

Vas deferens (diabetic)

Iliac or femoral vessels

Left upper quadrant calcifications are essentially always related to the spleen. Multiple small punctate calcifications are the result of histoplasmosis ( Fig. 6.11 ). Serpiginous or rounded calcifications in the left upper quadrant usually are related to splenic artery calcification or a splenic artery aneurysm ( Fig. 6.12 ).

With chronic pancreatitis, calcification of the pancreas often is found. This can be seen as spotted or mottled calcification, usually lying in a somewhat horizontal distribution over the vertebral bodies of L1 and L2 extending to the left. Remember, however, that on a plain abdominal x-ray, most persons with chronic pancreatitis do not have visible calcifications. CT scanning can identify calcifications much more easily than can a standard x-ray ( Fig. 6.13A ), but you should rely on the clinical and laboratory history, not on a CT scan (see Fig. 6.13B ), for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis.

Calcification of mesenteric lymph nodes can occur as a result of previous infections. These are usually seen as somewhat rounded or popcorn-shaped calcifications in the right midabdomen. A tip-off is the significant downward movement of these calcifications on the upright views because the mesentery is very mobile ( Fig. 6.14 ).

In a patient who has right lower quadrant pain, look carefully in this area for calcifications. A stone within the appendix (appendicolith) often projects over the right side of the sacrum ( Fig. 6.15 ) and can be difficult to see unless you look carefully. An appendicolith is present in approximately 10% of patients with appendicitis and, if you see an appendicolith, a high probability of appendicitis exists. Other signs of appendicitis are a bubbly gas collection (appendiceal abscess) in the right lower quadrant or a focal ileus (dilatation) of the nearby small bowel caused by the inflammatory reaction.

In adults, it is common to see rounded calcifications in the lower half of the pelvis. These almost always are 1 cm or less in diameter, and they are phleboliths (calcifications within pelvic venous structures). They are easy to identify because they often have a lucent or dark center ( Fig. 6.16 ). They can occasionally be confused with stones in the distal ureter and, if a patient has symptoms of renal colic or obstruction, it is often necessary to perform a noncontrast CT to determine which of the calcifications in the lower pelvis may be phleboliths or calculi.

Uterine fibroids can often be calcified. This type of calcification is similar to the popcorn type seen in the mesenteric lymph nodes. The difference is that fibroids are located in a suprapubic position and centrally in the pelvis. On occasion, these can be quite large and spectacular ( Fig. 6.17 ).

Two special types of calcification can be seen in the male pelvis. The first, prostatic calcifications, are found immediately behind the symphysis pubis. They are quite common and are the result of benign inflammatory disease. They are not associated with prostate cancer ( Fig. 6.18 ). The second and rarer type of calcification looks like a little set of antlers in the middle of the pelvis, projecting slightly above the symphysis pubis. This represents calcification of the vas deferens and almost always indicates that the patient has diabetes ( Fig. 6.19 ).

Acute Abdominal Pain

Acute atraumatic abdominal pain requires urgent evaluation. Evaluation of the location, onset, progression, and character of abdominal pain is necessary to begin developing a reasonable differential diagnosis. A thorough medical history and physical examination are necessary because abdominal pain may be associated with GI, genitourinary, cardiovascular, or respiratory disorders. An electrocardiogram may be necessary to exclude myocardial causes. In addition to a physical examination of the chest and abdomen, pelvic and rectal examinations also may yield useful information. Sudden onset of pain is often associated with bowel perforation, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cyst, aneurysm, or ischemic bowel. Gradually increasing and localizing pain is more common in appendicitis, cholecystitis, and bowel obstruction.

After the patient has been assessed clinically, a reasonable approach to imaging can be formulated. In most cases of acute abdominal pain, the best initial imaging study is an upright PA chest x-ray and a supine and upright view of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast (the so-called three-way abdomen). CT scanning is used when an abscess, aneurysm, or retroperitoneal pathology is suspected. Ultrasound is the best initial examination if a gallbladder, obstetric, or gynecologic cause is suspected.

Abdominal Trauma

The imaging done in cases of abdominal trauma depends largely on whether the trauma is blunt or penetrating and whether the patient is stable or unstable and how soon surgery may need to be done. If the patient is unstable, usually chest, abdomen, and pelvis radiographs are done. These can show free air, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, fractures, and metallic foreign bodies. This can be followed by f ocused a bdominal s onography for t rauma (so-called FAST ultrasound) to look for pericardial, pleural, and free peritoneal fluid. If the FAST scan is positive, surgery often follows. If there is penetrating trauma and the FAST scan is negative, surgery may still be necessary. If the patient is hemodynamically stable, a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast may be done. If there is significant hematuria, this should be followed with CT cystogram.

Acute Gastroenteritis

A diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis is made on the basis of clinical history and the presence of diarrhea. The patient also may have vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain. Dehydration is a common complication. The only procedure recommended is flexible sigmoidoscopy if blood is present in the stool.

Abdominal Masses

Palpable abdominal masses can arise from any organ or structure in the peritoneal space, retroperitoneum, aorta, bowel, pelvis, or abdominal wall. As a general rule, most abdominal masses do not grow down into the pelvis, but pelvic masses (being largely confined) often grow up into the abdomen. The initial imaging study should be a three-way view of the abdomen to look for associated thoracic pathology (such as metastases or effusions), abnormal gas collections, displacement of the bowel, renal outlines, or associated calcification. Although ultrasound imaging can be used to characterize an abdominal mass, in adults, CT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis with IV and oral contrast is usually obtained. Ultrasound is preferred for initial imaging in children.

Esophagus

Anatomy and Imaging Techniques

The appropriate initial imaging study for a number of suspected clinical problems is shown in Table 6.1 . Imaging of the esophagus for many problems is best done by direct visualization (endoscopy). Because this is a major procedure requiring sedation, many physicians begin by ordering an upper GI examination or contrast esophagogram. In addition to barium, other water-soluble contrast materials can be used. If a tear or perforation of the esophagus is suspected, it is best initially to use water-soluble contrast material rather than barium. If aspiration is suspected, barium is used because water-soluble contrast can irritate the lung.

| Suspected Clinical Problem | Imaging Study |

|---|---|

| Gastroesophageal reflux | |

| Mild or transient | Medical therapy |

| Severe or persistent | Endoscopy with biopsy |

| Esophageal obstruction or dysphagia | Barium swallow (biphasic esophagogram) |

| Esophageal tear | Meglumine diatrizoate (Gastrografin) swallow |

| Bowel perforation or free air | Upright chest and supine abdominal plain radiograph; supine and left lateral decubitus, if patient is unable to stand |

| Hematemesis | Endoscopy (less preferred, contrast UGI series) |

| Gastric or duodenal ulcer | Test for Helicobacter pylori ; if medical therapy fails, endoscopy or double-contrast UGI series |

| Trauma, blunt or penetrating | If patient unstable, chest, abdomen, and pelvis x-ray, US of abdomen and pelvis for free fluid; if stable, CT of abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast |

| Palpable abdominal mass | CT of abdomen with IV contrast or MRI of abdomen with and without IV contrast |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Supine and lateral view of abdomen, then US or CT with IV contrast |

| Acute pancreatitis (stable patient, first episode) | US of abdomen |

| Pancreatitis (critically ill) | CT of abdomen with contrast |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst follow-up | CT or US |

| Acute nonlocalized abdominal pain with fever (suspect abscess) | CT of abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast; US or MRI for pregnant patient |

| Liver lesion | MRI of abdomen with and without IV contrast |

| Acute cholecystitis | US or nuclear medicine hepatobiliary scan |

| Chronic cholelithiasis | Right upper quadrant US |

| Common duct obstruction | Right upper quadrant US |

| Jaundice | |

| Painful | US or CT with and without IV contrast |

| Painless, suspect biliary obstruction | CT with IV contrast, US of abdomen or MRI of abdomen with and without contrast with MCRP |

| Painless, suspect liver | US |

| Suspected bile leak | Nuclear medicine hepatobiliary study |

| Small bowel stricture or polyp | CT enterography |

| Intestinal obstruction | Supine and upright radiograph of abdomen as initial study, followed by those listed below: |

| Esophagus or stomach obstruction | UGI and small bowel series or endoscopy |

| Small bowel obstruction | CT of abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast |

| Distal small bowel or colon obstruction | Barium enema |

| Crohn disease | CT with IV contrast or CT enterography |

| Right upper quadrant pain | US of abdomen |

| Appendicitis | |

| Adults | CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast (US for pregnant female) |

| Children < 14 years | US-graded compression; CT of abdomen and pelvis with contrast if negative or equivocal US |

| Left lower quadrant pain, suspected diverticulitis | CT of abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast |

| Suspected pelvic abscess | CT with IV contrast or US |

| Ulcerative colitis | Colonoscopy (see text for screening); if incomplete or unavailable, barium enema |

| Ischemic colitis | CT with IV contrast |

| Suspected renal or ureteral stone | Noncontrast CT |

| Pelvic pain (female) | US |

| Bladder pathology | Cystoscopy; if not available, CT cystogram |

| Uterine or ovarian pathology | US |

| Abdominal tumor | CT with IV contrast |

| Colon cancer | Colonoscopy (see text for screening); if incomplete, double-contrast barium enema |

| Acute diverticulitis (left lower quadrant pain) | CT with IV contrast |

| Rectal Bleeding (obvious) | |

| Dark red | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; if not available, UGI series |

| Bright red | Colonoscopy |

| Unknown source or colonoscopy nondiagnostic | Nuclear medicine bleeding study |

| Positive fecal occult blood test | |

| > 40 years | Colonoscopy |

| < 40 years with GI symptoms | Helicobacter pylori test, therapeutic trial; if this fails, endoscopy or UGI series |

The normal esophagus has a rather smooth lining. Two indentations, due to impressions by the aortic arch and the left main stem bronchus, can be seen along the left side ( Fig. 6.20 ). Normally, a peristaltic wave, initiated by swallowing, propels food down the esophagus. You should not diagnose a stricture on the basis of one image alone because you may be looking at a normal area of peristaltic contraction. Sometimes, in the distal portion of the esophagus, a Z line can be seen going across the esophagus. This represents the junction between the mucosa of the esophagus and the stomach ( Fig. 6.21 ).

Dysphagia and Odynophagia

Initially, it is important to differentiate dysphagia (difficulty swallowing or sticking of food) from odynophagia (pain with swallowing). The most common cause of dysphagia is a hiatal hernia with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Patients with mild dysphagia do not need imaging or endoscopy but they should have a trial of GERD medical therapy. Patients with severe symptoms should be investigated with endoscopy or barium swallow.

Many patients 60 to 80 years of age have dysmotility and do not pass food properly. They generally have vague symptoms. A barium swallow is indicated to exclude other pathology. Patients who complain of food getting stuck often have a benign or malignant stricture. These usually require endoscopy with biopsy.

Difficulty swallowing can also be the result of central nervous system pathology. Pharyngeal paresis with ineffective constriction of muscles may be due to abnormalities involving cranial nerves IX and X, stroke, or degenerative changes. In these patients, failure to close the glottis often results in aspiration.

Odynophagia is usually due to an infection or medication that produces esophagitis. In these patients, a barium swallow can visualize ulcerations or other characteristic mucosal patterns (such as herpes). Endoscopy also can be used, with the advantage of a biopsy of visualized abnormalities.

Esophageal Diverticula

In the lower cervical region, sometimes a pharyngeal diverticulum (Zenker diverticulum) projects posteriorly. Food can be caught in this, causing dysphagia ( Fig. 6.22 ). In the middle of the esophagus (near the carina), a traction diverticulum may be caused by scarring from mediastinal granulomatous disease. Just above the stomach, a pulsion diverticulum can sometimes be found. The two latter types are rarely symptomatic.

Presbyesophagus

As a function of aging, tertiary deep contractions may develop within the esophagus. These are usually disordered and can interfere with the normal peristaltic process and swallowing. These tertiary contractions are easily visualized as multiple transverse or ringlike contractions of the esophagus ( Fig. 6.23 ). No specific therapy is indicated for this condition, and it is common in persons older than 60 years.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree