Chapter 29 Gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract has traditionally been examined using radiography, barium sulphate suspension (commonly referred to as ‘barium’ and used interchangeably) and gas as a double-contrast agent. Accessory organs of the tract (Chapter 30) have traditionally been examined using iodine-based contrast agents. However, the rapidly changing field of medical imaging, with the development of faster image acquisition, higher resolution, better computing power and improvements in post-processing software, now sees the tract examined by a variety of methods, some of which supersede conventional contrast radiography.1,2 Recent advances in the technology of multidetector computed tomography (CT) systems have increased the use of CT in the diagnosis of the small bowel.3 CT enterography and magnetic resonance (MR) enterography are now proving accurate in defining the extent and severity of small bowel inflammation and neoplasms, and detecting extraluminal pathology. Capsule endoscopy is another developing imaging modality used to examine the GI tract. It is highly sensitive but has a lower specificity, and there is also the risk of capsule retention.4–6 Virtual colonoscopy, primarily using CT (although MR may be used), is another advancing technology.7 Endoscopic ultrasound and positron emission tomography are also emerging supplementary technologies that may find a role in imaging of the GI tract.8,9 Some of these newer imaging techniques are complementary as opposed to alternatives to traditional barium studies.10 The use of videofluoroscopy or the ‘modified barium swallow’ is, however, a barium examination that has increased in popularity.

Notes on position terminology for fluoroscopic examination

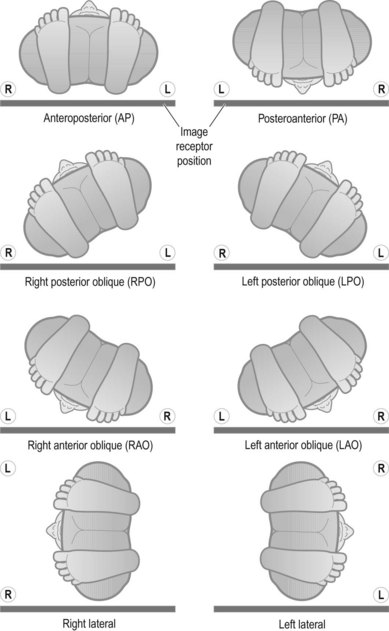

For example, if a patient is initially supine on a conventional radiography examination table (over-couch tube, under-couch IR) and their right side is then raised, the position is described as a left posterior oblique (LPO), as the patient is oblique with the posterior aspect of their trunk still in contact with the table-top (Fig. 29.1); on a fluoroscopy table with under-couch tube and over-couch receptor, this same body position is usually described as a right anterior oblique (RAO) as the right anterior aspect of the body is nearest the IR. Simpler projections such as anteroposterior (AP) change to posteroanterior (PA) with over-couch receptor and under-couch tube. Students in particular become very confused by this, and many radiographers resort to describing the positions as ‘right side raised’ or ‘left side raised’ to avoid confusion.

For the purpose of this chapter and to avoid this confusion, the authors have decided to use the traditional under-couch receptor and over-couch tube descriptor, identical to that used for general under-couch IR over-couch tube radiography. Figure 29.1 identifies the positions in full. We hope that this proves less confusing than using the traditional fluoroscopy description technique.

Upper GI tract

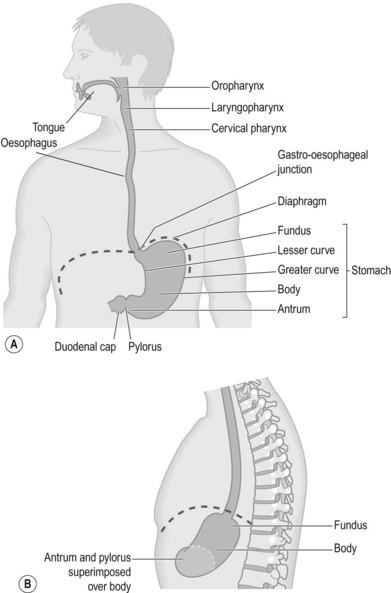

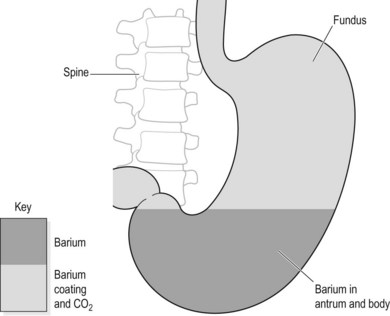

The upper GI tract consists of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, oesophagus, stomach and first part of the duodenum (for a general appraisal of the layout of this part of the GI tract see Figure 29.2). The aim of a contrast examination is to outline these structures in single and/or double contrast to obtain optimum visualisation. The most common contrast agent used is a barium sulphate suspension, although ionic and non-ionic contrast agents can be used.

Most patients who have upper GI symptoms are referred primarily for oesophagogastric duodenoscopy (OGD), but this may be used in conjunction with other tests so that a ‘gold standard’ approach is applied.11 For some symptoms there is, as yet, no acknowledged standalone gold standard.12 There are, however, sometimes reasons why contrast-enhanced X-ray studies are required: for example when patients cannot tolerate an OGD due to medical constraints; when patients simply refuse an OGD procedure; or when their symptoms persist after OGD results are found to be negative. Contrast examinations are the examination of choice in suspected cases of high dysphagia (above the sternal notch) and when motility issues such as achalasia are suspected.13

Patient preparation – all examinations of the upper tract

The patient should be starved for at least 6 hours before the examination,14 but 5 hours has been considered adequate.15 It is suggested that this should be the case even if only a barium swallow is indicated, in case views of the stomach are found to be required; this avoids the patient having to return for a second examination. However, medications must be taken as normal. This is because some diseases affect the swallowing process and effective medication often improves the mechanism of swallowing. One example of this is in the case of Parkinson’s disease. If drug therapy is suspended, swallowing may be compromised, resulting in inadequate imaging of the swallowing process.

• The patient should cease smoking for 6 hours. Smoking can increase the amount of stomach secretions, which can prevent the barium sulphate from coating the stomach mucosa adequately

• All jewellery or artefacts (e.g. hearing aids) should be removed

• Patient clothing should be removed and a radiolucent gown should be worn

• The patient should then be informed of the procedure (they should have received information with their appointment prior to attending) so they can give their consent

• Compliance with instructions on the starvation period should be checked

Barium swallow and meal

Upper (‘high’) barium swallow

Technique

If there is any query that the patient may aspirate the contrast agent, the initial swallow is best carried out using a water-soluble contrast, although aspiration of barium sulphate has been considered by some to be relatively harmless.14 Aspiration may not be suspected but unsuspected ‘silent aspiration’ may be found. Otherwise use the following technique (ensure that you have understood the notes on fluoroscopic examination positioning descriptors earlier in this chapter before considering technique descriptors):

• The patient is initially asked to stand erect in the AP position on the fluoroscopic table and hold the cup of barium sulphate in their hand, usually the left, as further turning of the patient is usually to the left. The arm will then lie clear of the trunk, without the patient having to negotiate its movement around the intensifying screen carriage.

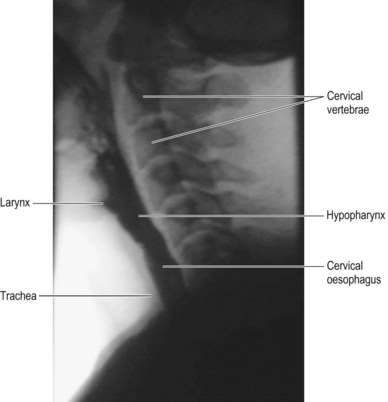

• The patient is turned into the left lateral position in order to commence with routine assessment of possible aspiration. They are asked to take a ‘normal’ (for them) mouthful of the liquid and hold it in their mouth until asked to swallow. This is to give the operator a chance to centre on the area of interest, the pharynx, and optimise the collimation. This view allows the posterior wall of the hypopharynx to be optimally viewed (Fig. 29.3). It also clearly shows the larynx and trachea, thereby allowing demonstration of laryngeal penetration and/or aspiration should it occur.

• If the radiographic equipment allows, a frame rate of 3 per second is suggested as an initial choice; modern digital equipment can allow recording of the screened image. This offers a reduction in radiation dose by allowing retrospective and repeated study of the patient’s swallowing action without returning to rescreen missed actions, and also allows a more real-time assessment to take place.

• The patient is then asked to swallow and the exposure is initiated. Real-time recording (exposure) is terminated when the barium bolus passes beyond the screened image or point of interest. This lateral pharynx view is then repeated, as some pathologies such as cricopharyngeal spasm may be transient and may not occur on every swallow.

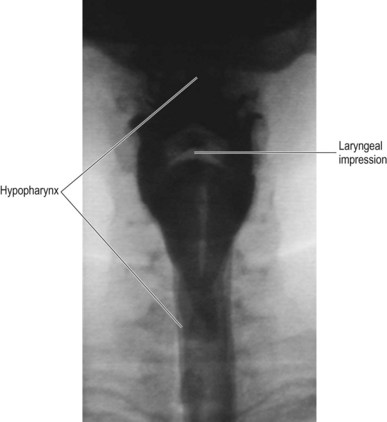

• The patient is then turned back to AP, ideally standing with their chin raised so that their symphysis menti is superimposed over the occiput. The AP view is the optimum for hypopharyngeal anatomy;16 it will be seen in both single- and double-contrast images (Fig. 29.4). This view may be repeated at least once more to ensure there is consistency in the images, making it easier to definitively identify pathology.

• Depending on the patient’s history and the individual imaging department protocols, the examination may be terminated at this point, or the lower oesophagus may be imaged with a check for reflux. Some lower oesphageal pathologies such as hiatus hernia and GOR may mimic ‘high’ pathology such as globus (see barium swallow and reflux assessment below).

The most common abnormalities in the pharynx are persistent cricopharyngeal impressions or diverticula, the most common diverticulum type being Zenker’s; this occurs in the mid-hypopharynx and is more common in the older population. They are quite often termed hypopharyngeal pouches.16 The pouches can become quite large, often causing patients to be referred because of regurgitation of undigested food some time after they have eaten. They are also often difficult to endoscope, as the scope enters the pouch and cannot be passed further; the barium swallow can thus quite often be the most appropriate test for confirming the presence and extent of this pathology.

Oesophageal webs are also best seen on the lateral projection, shown on the anterior wall, although they are best viewed with rapid imaging sequences; they have been noted in 1–5% of asymptomatic patients and 12–15% of dysphagia patients.16

Barium swallow and reflux assessment

Patients for this type of study often present with clinical symptoms of GOR. They often have a feeling of retrosternal discomfort and no other symptoms. Although pH monitoring is an effective way of evaluating GOR, there is not as yet a gold standard test.12 The barium study can still be useful as an adjunct to other tests, as some GOR patients may have small hiatus hernias that are not seen on endoscopy. These patients may have mucosal changes in the distal third of the oesophagus, such as oesophagitis or Barrett’s oesophagus. Barrett’s oesophagus is a premalignant condition known to be caused by GOR,17 so the swallow is used to view the region closely and observe the fundus to check for herniation.

Technique

• AP and lateral projections can be taken of the hypopharynx and upper oesophagus as previously described for the barium swallow

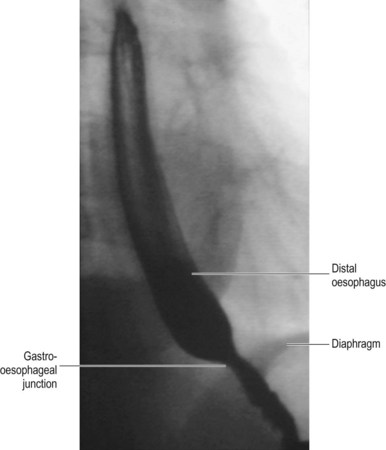

• A more useful view of the mid and distal thirds of the oesophagus is provided by the erect left posterior oblique, taken after the patient is asked to swallow. In this position the oesophagus does not lie over the thoracic spine and the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) is opened out, thereby ensuring clearer visualisation. The barium bolus is imaged as a column and spot films are taken to show the distal third of the oesophagus. This allows mucosal rings and peptic strictures to be shown well.16 As the column passes and the mucosa relaxes, spot films can be taken; this may show oesophagitis

• The patient is then asked to take the effervescent granules (either dry or mixed with a small amount of water if dry is too difficult) or other effervescent aid, followed by the citric acid. It is important to impress on the patient that these will produce gas in the stomach and may give them the feeling that they need to belch; it is imperative they do not succumb to temptation, and the best way to avoid this is to tell them to keep swallowing. Advance explanation of this, giving reasons for its importance, will maximise compliance

• The patient is then asked to swallow another mouthful of barium while in the LPO position (Fig. 29.5) and images can be taken of the lower oesophagus (either spot image recording or 1 frame per second is likely to be adequate). This will give a double-contrast examination of the oesophagus, allowing a good view of mucosal detail

• To detect signs of a hiatus hernia (if one has not been noted so far) or GOR, the fluoroscopic couch is then placed horizontally and the patient turned to their right to assess reflux. Spot images of the area are taken

• A prone swallow may also be undertaken at this point. The patient lies either completely prone with their head turned to one side or in the RAO position, which throws their oesophagus away from their spine. The patient then drinks some barium through a straw and the barium bolus is screened as it travels along the oesophagus. Spot films are also taken. This view maximises oesophageal distension and can also produce well-coated double-contrast views of the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction. It is a particularly good view to demonstrate oesophageal varices. A prone swallow must never be attempted if aspiration or laryngeal penetration is evident when erect

• The patient is then asked to rotate through 360° at their own pace; this will ensure that all aspects of the gastric mucosa are coated ready for assessment of the stomach. Ideally the patient turns to the left: this helps to prevent the barium from spilling into the duodenum before the stomach is coated and obscured by barium-filled small bowel. While they are performing this movement it is best to screen periodically in case any additional lower oesophageal pathology is noted so that a spot image of the lower oesophagus and GOJ can be taken. On completing this manoeuvre, further images of the stomach are taken at key stages:

• To show reflux actually occurring, the patient can be tilted head downwards (Trendelenburg position) as this mimics stress reflux, but as this is an artificial position it may have limited bearing on the accuracy estimation of the true extent of reflux. The patient can also be asked to cough while turning on to their right side, again to mimic reflux

• If reflux is demonstrated the freedom with which it occurs and the level it attains should be noted (e.g. free reflux to the cervical region), as this will be an aid to the clinician in the assessment of the patient. It is noted, however, that reflux may only occur in about a third of symptomatic patients5

Barium meal

This examination is performed to show the stomach and duodenum. It is becoming less frequently requested owing to the increase in the use of endoscopy as the front-line examination, and is recommended for use in a very limited number of circumstances. These include: if endoscopy proves negative and symptoms persist; after (healed) surgery to assess afferent loop, narrowed anastamoses, and closed loops or internal hernias,18 or to assess complications after bariatric surgery.19 It therefore can be seen that the barium meal can still be useful for those patients who are not considered fit for, or refuse, OGD.

Contrast agents and pharmaceutical aids for the examination

• Barium sulphate suspension 250% w/v

• Effervescent granules and citric acid, or other gas-producing agent

• An antispasmodic agent such as hyoscine-N-butyl bromide (Buscopan) may be used intravenously. These help to reduce peristalsis in the stomach and prevent rapid progress of the barium into the small bowel14

Technique

• The patient is asked to stand on the step of the fluoroscopic couch and then the procedure for ingesting the gas-producing agent is explained. The importance of keeping the gas in the stomach is emphasised, and an explanation of a strategy to prevent belching (dry swallowing) is given

• The patient is given the effervescent agent (dry, or mixed with a small amount of water if this is more tolerable for the patient); they are then asked to drink the citric acid, to produce carbon dioxide and distend the stomach

• The patient is turned slightly to their left and asked to swallow a mouthful of the barium; the barium column is screened and spot images are taken of the distal oesophagus with single and double contrast

• After three or four reasonable mouthfuls of barium have been ingested, the table is tilted horizontally and the patient asked to rotate (at least once) through 360° to enable the barium to coat the stomach mucosa. A prone swallow may also be undertaken at this point. Periodic screening during this movement allows for images to be taken if the radiographer feels it is necessary, especially if a small hiatus hernia or GOR are noted. This also enables the operator to note which positions show the anatomy most effectively, in preparation for other spot images. Quite often the most difficult region to image well can be the duodenal cap, owing to the peristaltic action of the small bowel (which can occur even after administration of intravenous muscle relaxant); therefore, if the duodenal cap is well visualised during the patient’s initial movements, there may be an opportunity to obtain the spot images required

• Once the patient has completed their rotation and good mucosal coating and distension of the stomach have been noted, it is possible to obtain the spot images. If coating is poor, give the patient more barium or ask them to perform another 360° rotation; if distension is inadequate then repeat the dose of effervescent agent. Because this is a dynamic investigation it is best to take the spot images as quickly as possible, and if the chance arises and an area is well shown while moving the patient, take the opportunity

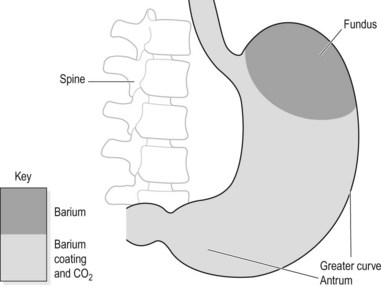

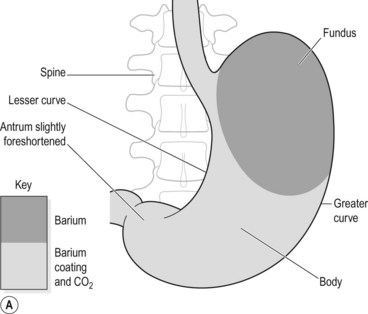

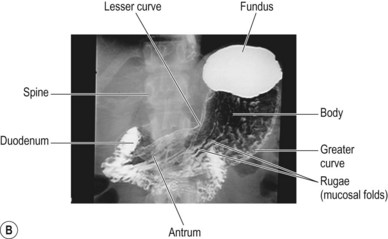

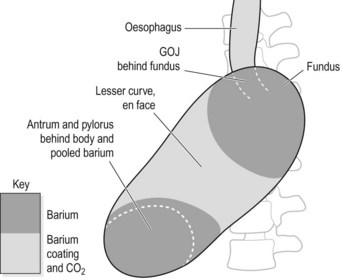

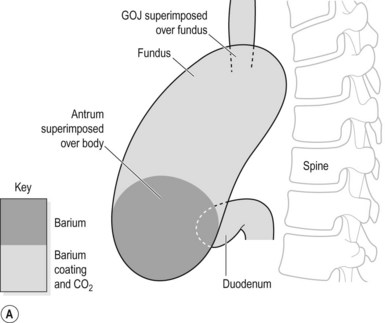

• The following positions are a general guideline to how best to show the anatomy of the stomach and duodenum in double contrast:

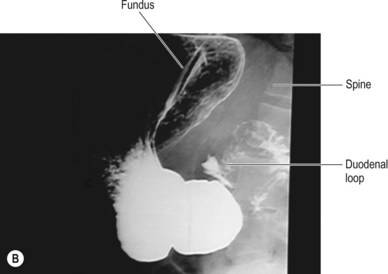

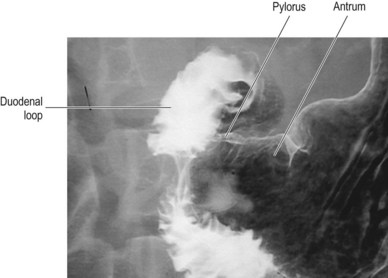

• A combination of the following positions will help to best demonstrate the duodenal loop and duodenal cap. It may be necessary to use magnification at this point to optimise the view:

• The patient can then be tilted erect and turned slightly to the left to show the fundus (Fig. 29.11). If visualisation of the duodenal cap has been poor during the earlier (table horizontal) stages of the examination, turning the patient in both directions (while they are standing) may provide better views of the duodenal cap

Aftercare

• A damp tissue should be provided for the patient to clean their mouth

• The patient should be informed that their stools will be paler or white for a few days, and to keep their fluid intake up to reduce any chance of constipation. Encourage a high-fibre diet for several days

• Ensure that the patient knows how to obtain their results

• If a muscle relaxant is used, the patient must remain in the department until any blurring of their vision has passed