Abstract

The gastrointestinal tract poses challenges for interpretation on FDG PET/CT, as esophagus, stomach, small and large bowel may all demonstrate physiologic FDG avidity, and physiologic FDG avidity may be even more intense than a coexisting malignancy. An important concept is to define the GI tract FDG avidity as focal or nonfocal. Another important concept is to correlate the FDG avidity in the GI tract with corresponding findings on the CT images. Identifying focal versus nonfocal FDG avidity and corresponding wall thickening or masses on CT will help distinguish benign from malignant FDG avidity in the gastrointestinal tract.

Keywords

FDG, PET/CT, gastrointestinal tract, esophagus, stomach, small bowel, large bowel, colon

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract poses challenges for interpretation on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT). The esophagus, stomach, and small and large bowel may all demonstrate physiologic FDG avidity, and physiologic FDG avidity may be even more intense than a coexisting malignancy. The areas of physiologic FDG avidity on imaging at one time point may not be the same as the areas of physiologic FDG avidity at another time point. Benign inflammatory etiologies such as esophagitis and gastritis may also be FDG avid. Medications, such as metformin, may induce substantial FDG benign avidity in the colon. These sources of benign FDG avidity may obscure underlying FDG-avid malignancy and may also be mistaken for malignancy.

The differential diagnosis of lesions along the GI tract is similar for the different organs, although the frequency of each type of malignancy will vary at the different organ sites. The differential diagnosis of a malignancy includes primary tumors, lymphoma, and metastases. Primary malignancies of the GI tract include squamous and adenocarcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoid), and mesenchymal malignancies (GI stromal tumors [GISTs] or rare leiomyosarcomas). Involvement of multiple sites along the GI tract, as well as corresponding widespread nodal enlargement, favors lymphoma. Lymphoma may also be suggested by “aneurysmal dilation” of bowel lumen, rather than narrowing of the lumen, which is more typical with other genitourinary (GU) tract malignancies. Benign lesions of the GI tract which may be FDG avid include esophagitis and gastritis from stomach acid, infections, ischemia, radiation inflammation, and idiopathic bowel diseases (Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis).

An important concept is to define the GI tract FDG avidity as focal or nonfocal. Another important concept is to correlate the FDG avidity in the GI tract with corresponding findings on the CT images. Small focal FDG avidity in the GI tract without a CT correlate may be physiologic or represent a lesion which is occult on CT, and thus further evaluation may be warranted. If a small focus of FDG avidity corresponds with a polyp or mass on CT, a lesion is confirmed and further evaluation is warranted. Nonfocal FDG avidity (such as large segments of FDG-avid GI tract), without CT correlate, are probably physiologic. Large segments of FDG avidity in the GI tract associated with wall thickening or mass on CT are abnormal, and further evaluation is warranted.

Oral contrast will help to distend the lumen of the GI tract, which helps to visualize wall thickening and masses. Oral contrast is a valuable component of CT and PET/CT studies when the GI tract is a focus of investigation and should be included whenever possible. Some investigators also include intravenous contrast because contrast enhancement will help to visualize enhancing bowel wall masses as well as distant metastases.

Esophagus

The most common malignancies of the esophagus are squamous and adenocarcinomas. Endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound are the most accurate means of staging a primary esophageal malignancy. On CT the primary esophageal cancer may be visualized as wall thickening or a focal mass. If the malignancy causes obstruction, then the esophagus may be dilated proximal to the malignancy. If advanced, the mass may demonstrate direct invasion of structures adjacent to the esophagus. Both squamous and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus usually demonstrate high FDG avidity; however, mucinous and signet ring histologies often have lower FDG avidity. A primary esophageal malignancy may be visualized on FDG PET, CT, or both. Small primary esophageal malignancies may not be visible on either FDG PET or CT.

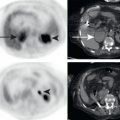

Esophageal cancer demonstrates lymphatic spread to local lymph nodes, usually in the mediastinum for upper esophageal malignancies and also in upper abdominal nodes for lower esophageal malignancies. FDG PET/CT has demonstrated value for the detection of local subcentimeter nodal metastases from esophageal cancer which may be overlooked on anatomic imaging. Nodal metastases in the mediastinum may involve the vagus or recurrent laryngeal nerves, resulting in vocal cord paralysis ( Fig. 16.1 ).

Hematogenous spread to any site is possible, with the most common hematogenous metastases being seen in the liver. Contrast-enhanced CT is the standard imaging modality for evaluation of distant metastases; however, FDG PET/CT may demonstrated unsuspected distant metastases not visualized on anatomic imaging, resulting in upstaging of malignancy and alterations in therapeutic management.

Following therapy of esophageal cancer, FDG PET/CT may help to visualize therapy response ( Fig. 16.2 ). It is important to realize that treatment response in solid tumor such as esophageal cancer cannot be compared with treatment response in lymphoma. For lymphoma, residual FDG avidity below liver background is considered treated disease. For solid tumors such as esophageal cancer, reduction of FDG avidity correlates with treatment response, but complete response cannot be distinguished from partial response. Low-volume residual malignancy may be present, despite reduction to background FDG avidity. Tissue sampling would be needed to distinguish partial from complete pathologic response.

The most common malignancies of the esophagus are primary esophageal squamous and adenocarcinomas; however, it is important to remember that the differential for malignant esophageal masses also includes less common esophageal neuroendocrine tumors, mesenchymal tumors, lymphoma, and metastases.

The esophagus may demonstrate physiologic or inflammatory FDG avidity, which must be distinguishing malignancy. In some cases, corresponding CT can help to distinguish benign from malignant esophageal FDG avidity. Small focal areas of FDG avidity may represent esophageal malignancy even without any CT correlate. However, larger segmental areas of FDG avidity are usually accompanied by wall thickening or mass on CT if they are malignant. Larger segmental areas of FDG avidity in the esophagus, without corresponding CT abnormality, are often physiologic or inflammatory. For example, this may be seen with postradiation esophagitis ( Fig. 16.3 ).

If FDG avidity is associated with wall thickening or mass on CT, the FDG avidity is not physiologic. These findings may be malignant or benign (e.g., inflammatory conditions such as Barrett esophagus) ( Fig. 16.4 ). Barrett esophagus is a chronic inflammatory condition secondary to gastric reflux. Endoscopy and biopsy may be needed for workup of incidental FDG avidity in the esophagus to distinguish between benign and malignant etiologies.

Stomach

Adenocarcinomas are the most common malignancies of the stomach. Endoscopy and biopsy are the most accurate means for diagnosis of a primary gastric malignancy. On CT, the primary gastric malignancy may be visualized as wall thickening or focal mass. An undistended stomach may seem to have gastric wall thickening or a mass which actually does not exist, and these “pseudotumors” must be distinguished from true masses. In a stomach distended with gastric contents or oral contrast, the evaluation of wall thickening or focal masses is more reliable. On FDG PET, focal FDG avidity may be seen at the site of the primary malignancy; however, FDG PET is not sensitive for the detection of a primary gastric malignancy. This is particularly true for mucinous and signet ring histologies, which demonstrate lower FDG avidity. Overall, primary gastric malignancy may be visualized on FDG PET, CT, or both, whereas small primary gastric malignancies may not be visible on either FDG PET or CT.

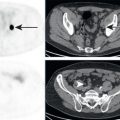

Gastric malignancies demonstrate lymphatic spread to local lymph nodes, usually beginning with perigastric nodes, then extending of the regional nodes along the celiac artery and its branches. FDG PET, like CT, has demonstrated low sensitivity for the detection of gastric lymph node metastases; thus a lack of FDG-avid or enlarged nodes on FDG PET/CT does not exclude regional nodal metastases. FDG PET has relatively higher specificity for detection of nodal metastases within draining nodal basins and may identify subcentimeter nodes suspicious for metastases which are overlooked on anatomic imaging ( Fig. 16.5 ). Nodal drainage to the thoracic duct may result in left supraclavicular nodal metastases, which are considered distant metastases.

Hematogenous spread to any site is possible, with the most common hematogenous metastases being seen in the peritoneum and liver. Contrast-enhanced CT is the standard imaging modality for evaluation of distant metastases from primary gastric malignancies. The value of FDG PET/CT in the initial systemic staging of gastric malignancy has not been proven.

Following therapy, FDG PET/CT may help to visualize therapy response. FDG PET may be able to distinguish responders from nonresponders following chemotherapy or radiation therapy. FDG PET cannot distinguish complete pathologic response from partial pathologic response in gastric malignancies. This is due to physiologic and inflammatory FDG avidity in the stomach, as well as inability for FDG PET to sensitively visualize small-volume residual malignancy.

Gastric adenocarcinomas are aggressive with high rates of recurrence. The most common sites of recurrence for gastric malignancies are at the resection margins, peritoneum, and liver. There may be value for FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of recurrent gastric malignancy.

The most common malignancy of the stomach is adenocarcinoma; however, it is important to remember that the differential for gastric masses also includes less common gastric carcinoids, GISTs ( Fig. 16.6 ), lymphoma, and metastases ( Fig. 16.7 ). In some cases, FDG PET/CT may demonstrate gastric wall thickening without significant FDG avidity. Thus gastric wall thickening may be the only sign of a gastric malignancy ( Fig. 16.8 ). Endoscopy and biopsy may be needed for workup of incidental focal FDG avidity or wall thickening in the stomach.

The stomach may demonstrate physiologic or inflammatory FDG avidity, which must be distinguished from malignancy ( Fig. 16.9 ). In some cases the corresponding CT can help to distinguish benign from malignant gastric FDG avidity. Small focal areas of FDG avidity may be benign ( Fig. 16.10 ) or represent a gastric lesion which is occult on CT. Larger segmental areas of FDG avidity in the stomach are normally accompanied by wall thickening or mass on CT if malignant. Larger segmental areas of FDG avidity without corresponding CT abnormality are probably benign. If FDG avidity is associated with wall thickening or mass on CT, then the FDG avidity is not physiologic. Unfortunately, the PET/CT findings of benign and malignant gastric processes demonstrate substantial overlap. Endoscopy and biopsy may be needed to distinguish between benign and malignant etiologies of gastric FDG avidity or wall thickening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree