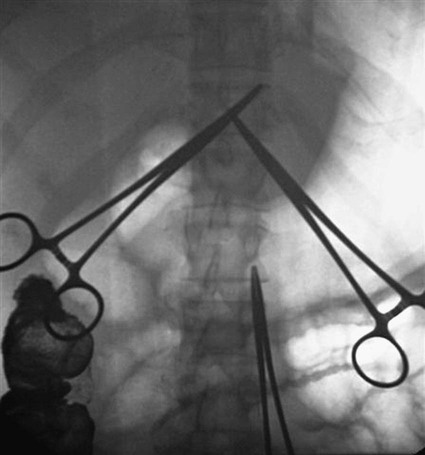

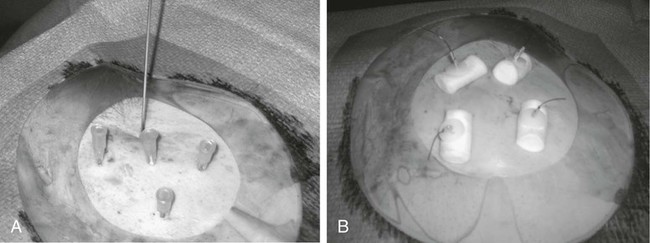

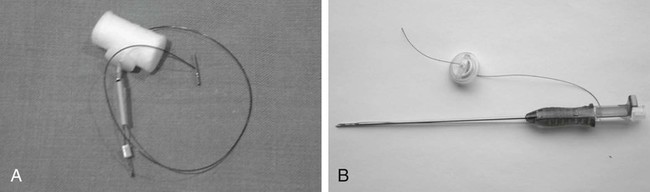

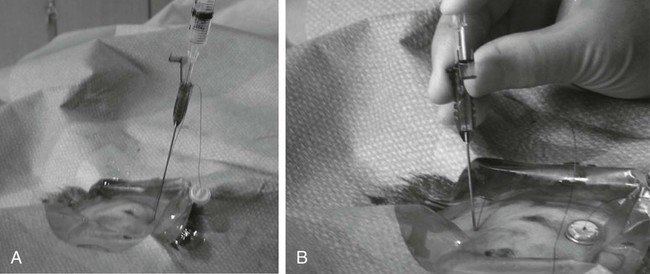

Traditionally, enteral feeding tubes were placed by surgical or endoscopic techniques, but the interventional radiologist now plays a central role in providing patient enteral nutrition by placing gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy tubes. The first successful placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) was described in 1979 by Gauderer and Ponsky.1 This was followed 2 years later by the first percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy (PRG) performed under fluoroscopic guidance by Preshaw.2 PRG is a well-tolerated procedure that provides nutritional support where required. The procedure is associated with low morbidity and mortality,3 with recent technical advances improving the long-term patency of enteral catheters.4 The advantage of PRG is the relative simplicity of the technique, facilitating enteral feeding in either the hospital or home environment. PRG is indicated in a wide range of patients who cannot maintain their nutrition orally. The most common patient subgroups are those with neurologic impairment resulting in absent gag reflex or disorders of swallowing, and esophageal or head and neck malignancy.3–6 Indeed, PRG is particularly advantageous in these patient subgroups, since it can be performed with minimal sedation, thereby decreasing the risk of aspiration,7,8 and avoidance of endoscopy, which is often precluded by upper tract stenosis in the case of malignancy.9 Other patient groups who benefit from gastrostomy placement and enteral feeding include those with intestinal malabsorption secondary to small bowel pathology such as Crohn disease, radiation enteritis, and scleroderma; patients who require supplementary enteral support, such as those with cystic fibrosis or significant burns; and patients with psychological ailments such as eating disorders or profound depression.10,11 Less commonly, gastrostomy is placed for decompression of gastrointestinal (GI) obstruction.3,11–13 Patients with diabetes-related gastroparesis can benefit from dual-lumen cannulation13; one lumen decompresses the stomach while a distal limb is placed beyond the ligament of Treitz for feeding. When not feeding during the day, the two loops are attached, obviating the need for a drainage bag.10 Difficulties with percutaneous access to the stomach, such as interposition of the colon between the stomach and anterior abdominal wall, or a large/low-lying liver are considered relative contraindications. In the case of colonic interposition, an infracolic approach is possible.14,15 Previously it was thought that gastric fixation (gastropexy) should not be performed with this approach, owing to the increased potential for complications including colonic obstruction. However, more recently an infracolic approach with gastropexy has been described with no additional complications.14 In the presence of a low-lying or large liver, computed tomography (CT) and/or ultrasound can facilitate gastric cannulation.11 PRG placement can be challenging in patients with a high-lying stomach, often seen in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and due to diaphragmatic weakness; an intercostal approach may be required.7 Previous surgery (e.g., Billroth II gastroenterostomy, partial gastrectomy, or gastric pull-through surgery) is considered a relative contraindication owing to anatomic distortion.16 Balloon distension of the stomach remnant and/or CT-guided placement of the gastrostomy tube may render the procedure possible.17–19 In head and neck or esophageal malignancy, significant stenosis of the upper GI tract may preclude placement of the nasogastric tube required for gaseous distension of the stomach. In such cases, a small-diameter catheter and hydrophilic guidewire may be used to cross the stenosis9; alternatively, the stomach can be punctured under ultrasound20 or CT guidance.21 The presence of ascites is no longer considered an absolute contraindication to PRG placement,21 and most interventional radiologists will perform the procedure in the presence of mild ascites. In the case of significant ascites, preprocedural paracentesis and gastropexy is mandatory to reduce the risk of catheter looping in the peritoneal cavity, tube dislodgement, and peritubal leakage.11 It is also necessary to prevent reaccumulation of ascites post procedure, since the weight of fluid can result in separation of the stomach from the anterior abdominal wall despite gastropexy.22 Sonographic follow-up and repeated paracentesis should therefore be performed as required. Patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis require similar consideration. The presence of gastric varices, as in portal hypertension, remains one of the only absolute contraindications to PRG because of the associated risk of significant hemorrhage.11,12 The required equipment for PRG insertion is detailed in Table 132-1. TABLE 132-1 List of Equipment Required for Standard Gastrostomy Tube Insertion The procedure and potential complications are discussed with the patient, and informed consent is obtained. A coagulation study is performed and any abnormalities corrected. The patient is required to fast from the evening prior to the procedure, and a nasogastric tube (NG) placed. Approximately 200 mL of dilute barium suspension can be administered (orally or via NG) 12 hours prior to the procedure to help identify the colon so it can be avoided during PRG. However, similar to other investigators,23,24 we have discontinued routine use of barium in our unit because we find gas in the colon is usually a sufficient marker when lateral screening is used. If there is insufficient gas in the colon, a small amount of air can be insufflated per rectum. Although advocated by some, particularly in head and neck cancer patients,25 antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely administered in our unit unless a hybrid PEG/PRG procedure is planned, as described later. The following is a description of the technique for placing a standard gastrostomy tube with gastropexy under fluoroscopic guidance. Figures 132-1 through 132-6 illustrate various aspects of the insertion technique. Certain tube types, such as low-profile gastrostomies, require some modification of technique, and this is addressed later in the chapter with the discussion on tube types. An appropriate puncture site for gastrostomy is chosen using fluoroscopy and anatomic landmarks; we do not routinely use ultrasound to delineate the liver edge. The optimum insertion site is usually to the left of midline overlying the antrum or mid- to distal body of the stomach, equidistant from the greater and lesser curves to avoid gastric and gastroepiploic vessels, and lateral to the rectus muscle to avoid the inferior epigastric vessels.12,21 A curved artery forceps is placed over the planned puncture site under fluoroscopy to confirm the proposed gastropexy position (Fig. 132-1). Local anesthetic (5-10 mL 1% lignocaine) is infiltrated at the four corners of a 2-cm square surrounding the planned puncture site (Fig. 132-2, A), and the gastropexy is formed using four T-fasteners, one at each corner of the gastropexy square (Fig. 132-2, B). Traditional T-fasteners (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.) (Fig. 132-3, A) consist of a nylon suture with a metal T-bar, cotton pledget, two metal cylinders, and a plastic washer, and are inserted into the distended stomach using a slotted 18-gauge needle. A syringe containing sterile saline is attached to the slotted needle, and an intragastric position confirmed by aspiration of air into the syringe. A stylet is then passed through the slotted needle to deploy the T-fastener. Stylet and needle are subsequently removed, and the stomach is approximated to the anterior abdominal wall by gentle traction on the T-fastener suture. T-fasteners are then secured in position by crimping the small metal cylinders at the base of the nylon suture. Such T-fasteners require removal post procedure. More recently we have switched to using T-fasteners with an absorbable suture (Saf-T-Pexy T-fasteners, Kimberley Clark, Draper, Utah) (Fig. 132-3, B) that do not require postprocedure removal. Their insertion technique is described in Figure 132-4, A and B. Following gastropexy, the center of the square is anesthetized, an incision is made using a #11 blade, and the subcutaneous tissue dissected. An 18-gauge needle is inserted through the incision and into the stomach (Fig. 132-5). Usually the puncture needle is directed vertically downward or slightly toward the fundus, but if conversion to a gastrojejunostomy procedure is anticipated, the needle should be directed toward the pylorus.12 Again, aspiration of air confirms an intragastric position, and a 0.035-inch Amplatz Super Stiff guidewire (Boston Scientific) is introduced through the needle and coiled within the gastric lumen. The percutaneous tract is then dilated to a size 2F larger than the selected catheter, and each dilatation is monitored fluoroscopically. Previously we used a series of fascial dilators for tract dilatation. More recently we have switched to using a gastrostomy kit from Kimberley Clark that contains a serial telescoping dilator with an integrated peel-away sheath (Fig. 132-6). This eliminates the need for multiple dilators and a separate peel-away sheath and is available in a variety of sizes dependent on the French size of the gastrostomy tube. Alternatively, an angioplasty balloon can be used to dilate the tract.4,26 As noted earlier, if the T-fasteners used do not have an absorbable suture, they are removed 48 hours after tube placement. This is performed at the bedside by gently lifting each T-fastener away from the abdominal wall and cutting the suture, allowing the metal T-bar to fall into the gastric lumen. Traditionally, the recommended time for removal of T-fasteners was 7 to 12 days, but we advocate early removal of T-fasteners. In a study conducted in our unit, early removal of T-fasteners resulted in reduced postprocedural pain and superficial skin infection.27 Once the patient is discharged, regular review by trained personnel (e.g., public health nurse or dietician) should be performed. Skin excoriation due to peritubal leakage of gastric juices can be problematic to deal with, and neutralization of acid with standard antacids may be beneficial, along with local skin cleansing. Local superficial infections can be treated with topical antibiotic ointments, but systemic antibiotics are required should signs such as fever or raised white cell count develop.11 Potential complications of gastrostomy placement are discussed later in the chapter. Any complications relating to the gastrostomy placement should be referred to the interventional radiologist who performed the procedure.

Gastrostomy and Gastrojejunostomy

Indications

Contraindications

Equipment

Equipment

Comments

Nasogastric tube and air insufflation balloon

Placed prior to procedure

200 mL of dilute barium suspension

Optional; colonic air usually visible fluoroscopically

Noninvasive monitoring equipment

To monitor HR, BP, oxygen saturation

Paralytic agents

Hyoscine-N-butylbromide or glucagon hydrochloride

Local anesthetic

1% lignocaine

Medications for conscious sedation

Fentanyl citrate, midazolam

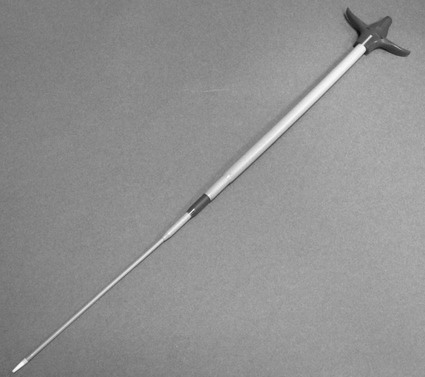

T-fasteners, slotted needle, and stylet

For gastropexy

10-mL syringe with 5-mL sterile saline

For gastropexy and gastric puncture

18-gauge needle

For gastric puncture

0.035-inch Amplatz Super Stiff guidewire

Serial fascial dilators or tapered dilator

Gastrostomy catheter of choice

Peel-away sheath

If balloon retention type catheter used

Contrast medium

To confirm placement

Gastrostomy

Patient Preparation

Technique

Postprocedural and Follow-up Care

Gastrostomy and Gastrojejunostomy