Genitourinary Diseases

NEPHROLITHIASIS (RENAL CALCULI)

SMALL RENAL MASS (RENAL CELL CARCINOMA)

OTHER SMALL RENAL MASSES (ANGIOMYOLIPOMA)

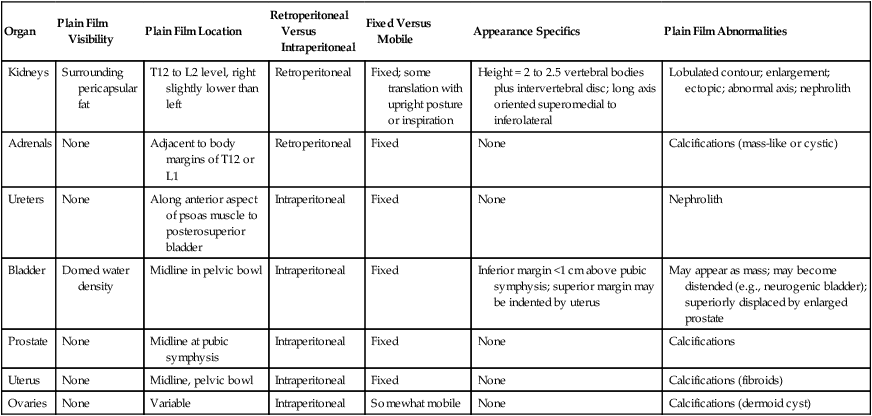

Portions of the genitourinary system are readily visible on plain film radiographs, which may aid in the localization of abnormal densities. This is a common site for concretions and some calcifying masses. Table 29-1 lists the common appearance of the genitourinary system and some of the abnormal findings that may be visible on plain film.

TABLE 29-1

GENITOURINARY PLAIN FILM ORGAN APPEARANCE

| Organ | Plain Film Visibility | Plain Film Location | Retroperitoneal Versus Intraperitoneal | Fixed Versus Mobile | Appearance Specifics | Plain Film Abnormalities |

| Kidneys | Surrounding pericapsular fat | T12 to L2 level, right slightly lower than left | Retroperitoneal | Fixed; some translation with upright posture or inspiration | Height = 2 to 2.5 vertebral bodies plus intervertebral disc; long axis oriented superomedial to inferolateral | Lobulated contour; enlargement; ectopic; abnormal axis; nephrolith |

| Adrenals | None | Adjacent to body margins of T12 or L1 | Retroperitoneal | Fixed | None | Calcifications (mass-like or cystic) |

| Ureters | None | Along anterior aspect of psoas muscle to posterosuperior bladder | Intraperitoneal | Fixed | None | Nephrolith |

| Bladder | Domed water density | Midline in pelvic bowl | Intraperitoneal | Fixed | Inferior margin <1 cm above pubic symphysis; superior margin may be indented by uterus | May appear as mass; may become distended (e.g., neurogenic bladder); superiorly displaced by enlarged prostate |

| Prostate | None | Midline at pubic symphysis | Intraperitoneal | Fixed | None | Calcifications |

| Uterus | None | Midline, pelvic bowl | Intraperitoneal | Fixed | None | Calcifications (fibroids) |

| Ovaries | None | Variable | Intraperitoneal | Somewhat mobile | None | Calcifications (dermoid cyst) |

Bladder Calculi

Background

Bladder outlet obstruction from prostatic disease remains the most common cause of bladder calculi in adults with the majority occurring in elderly men.11,20 Other factors predisposing to bladder stone formation are previous lower urinary tract surgery, metabolic abnormalities, upper urinary tract calculi, intravesicular foreign bodies, spinal cord injuries, and transplant surgery.11 The presence of bladder stones is associated with an increased incidence of carcinoma.20

Imaging Findings

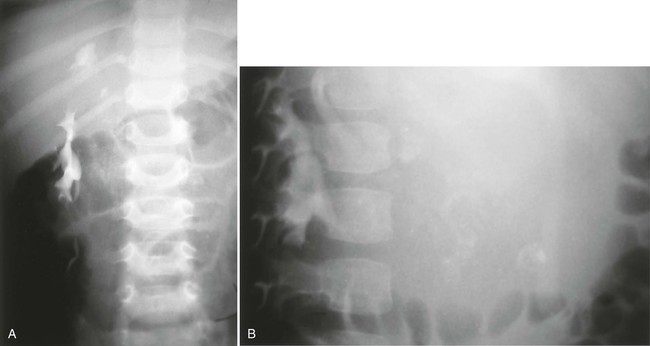

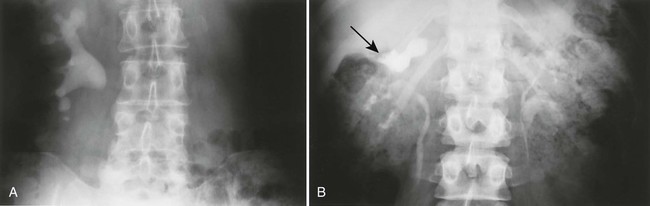

Bladder calculi often are nonopaque or only faintly opaque, allowing them to be frequently overlooked. Fecal material and gas in the rectosigmoid colon and the sacrum itself also overlie the area and may further obscure them. Bladder calculi usually are located centrally in the pelvis (Fig. 29-1). Those that are found more laterally may lie in a bladder diverticulum.20

Clinical Comments

The presentation of vesical calculi varies from completely asymptomatic to symptoms of suprapubic pain, dysuria, intermittency, frequency, hesitancy, nocturia, and urinary retention. Bladder calculi may abrade and irritate the mucosa and predispose to infection. Bladder infections are more difficult to treat when calculi are present. Ureteral or bladder outlet obstruction may also be present.20 Approximately 15% of patients with gout, as well as hyperuricemic patients, produce uric acid stones.20

Standard treatment of bladder stones consists of endoscopic visualization and fragmentation by electrohydraulic probe.46 Massive calculi may require open surgery.46

Nephroblastoma (Wilms Tumor)

Background

Nephroblastoma (Wilms tumor) is the most common abdominal malignancy in childhood.9,17 Overall, leukemia and lymphoma, brain tumors (astrocytoma and medulloblastoma), and neuroblastoma have a higher incidence in pediatric populations when other sites of the body are also considered.27 The highest incidence occurs in 3- and 4-year-old children, with 80% of Wilms tumors occurring in children 1 to 5 years old.3,6,27

Imaging Findings

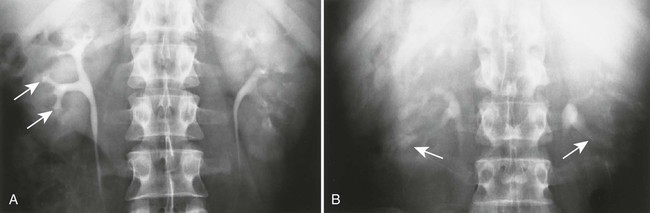

Wilms tumor appears radiographically as a complex renal mass (Fig. 29-2). Approximately 5% to 10% of these lesions show areas of calcification, but calcium, when seen in a mass in this area, is much more likely to be in a neuroblastoma of the adrenal or other similar tissue.27 Intravenous pyelography shows either a displaced or a nonfunctioning kidney. Ultrasonography typically reveals a well-defined tumor, often surrounded by a hyperechoic halo of compressed normal renal tissue.17,21 Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) usually reveals a large intrarenal mass of lower attenuation than the adjacent normal kidney. Cystic spaces or areas of tumor necrosis appearing as inhomogeneous, low-density areas are seen in most tumors.17

Clinical Comments

Patients with Wilms tumor present with an abdominal mass in more than 90% of cases.17 Approximately 50% of patients experience hypertension or fever. Hematuria is relatively uncommon.17,27 No male or female predominance is noted.17 Up to 30% with the rare condition of aniridia (congenital absence of the iris) develop nephroblastoma.27 A total of 4% to 5% of cases show bilateral tumors.27

Nephrocalcinosis

Background

Calcifications in the kidney are generally thought of as systemic conditions influenced by the concentration of a calcium, phosphate, oxalate, and on environment factors such as pH, osmolarity, and the concentration a variety of inhibitory molecules and proteins (e.g., citrate).39 Based on its location, calcification in the kidney can be classified broadly into two categories: calcification within the pyelocalyceal lumina, known as nephrolithiasis, and intraparenchymal calcification, termed nephrocalcinosis. Nephrocalcinosis also can be categorized with respect to its predominant location. A limited group of diseases, cortical nephrocalcinosis, may produce calcification confined to, or predominantly located in, the renal cortex. Other conditions, such as medullary nephrocalcinosis, spare the cortex and cause calcium salt deposition in the medulla, interstitium, or lumina of the nephrons.

Imaging Findings

Radiographically, cortical nephrocalcinosis can be differentiated from the medullary variety by the peripheral location of the calcification. Medullary calcification is typically that of bilateral, diffuse, fan-shaped clusters of stippled calcifications, primarily in the renal pyramids (Fig. 29-3). Although precipitating conditions are most often systemic, the presentation of calcification is not universally bilateral and symmetrical. Unilateral and focal presentations are common (Fig 29-4), suggesting that intrinsic factors, such as vascularity, may be involved.

Clinical Comments

The two most common etiologies of cortical nephrocalcinosis are acute cortical necrosis and chronic glomerulonephritis, although radiographically evident calcification is rare in both conditions. Persons on chronic dialysis may have similar calcifications.

Roughly 40% of cases of medullary nephrocalcinosis are attributable to primary hyperparathyroidism, another 20% to renal tubular acidosis, and the remaining 40% divided among many other causes.

Nephrolithiasis (Renal Calculi)

Background

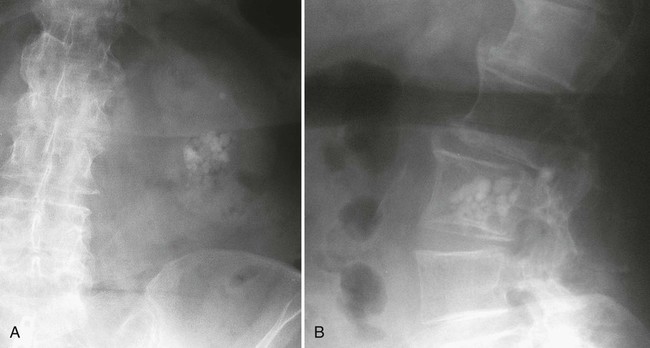

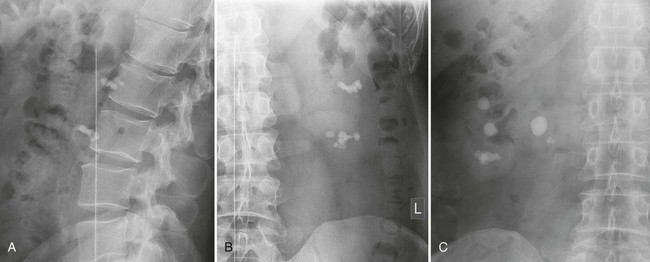

Whereas nephrocalcinosis is calcification in renal parenchyma, nephrolithiasis is concretion calcification in the luminal portion of the urinary tract (Figs. 29-5 and 29-6). The composition of renal stones varies with geography. In the United States, approximately 75% of renal stones are calcium oxalate. The remaining 25% of renal calculi are noncalcareous and are composed of uric acid, struvite, or cystine.

Imaging Findings

Ultrasonographically, most stones larger than a few millimeters show shadowing. However, ultrasonography is not the procedure of choice in diagnosis because too many false-negative studies exist. In intravenous pyelography, the radiolucent stones can be difficult to differentiate from blood clots or sloughed tissue. (All of these can obstruct drainage from the kidney.) With CT, all stones are denser than unenhanced renal parenchyma and urine.

Segments of the urinary tract proximal to the stone may show varying degrees of dilatation depending on the degree and chronicity of occlusion created by the stone (Fig. 29-7). Not all dilated drainage systems are from stones and other intrinsic filling defects; crossing bands of vessels or congenital narrowing can give the same appearance on intravenous pyelograms. Up to 90% of renal calculi are opaque enough to be seen on plain film radiographs.

Clinical Comments

Low urine volume and stasis contribute to formation of both calcareous and noncalcareous stones by increasing the urinary concentration of stone-forming constituents.

Renal calculi in the ureters cause renal colic, which has a dramatic clinical presentation, often with severe flank pain. Stones remaining in the renal pelvis may lead to obstruction. If they pass into the bladder, on unusual occasions, they may act as the nidus of a bladder calculus.

Ovarian Dermoid Cysts (Mature Cystic Teratoma)

Background

Mature cystic teratoma is the most common germ cell neoplasm and the most common childhood ovarian tumor comprising 10% to 25% of all ovarian tumors.42

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree