Chapter 27 Gynaecological cancer

Anatomy

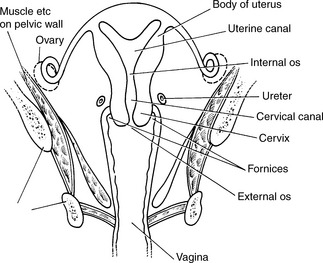

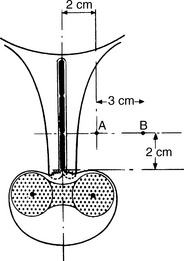

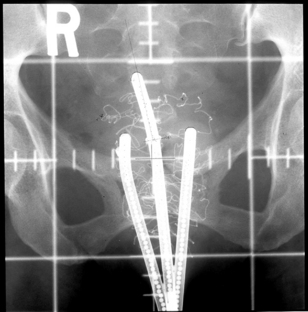

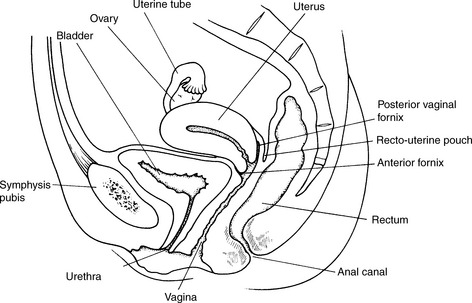

The female reproductive organs lie within the pelvis and are the vulva, vagina, uterus and fallopian tubes. These are represented in Figures 27.1 and 27.2.

Figure 27.1 Sagittal section of the uterus and its relations.

(Redrawn from Ellis, Clinical Anatomy, 5th edn, Blackwells, 1975).

Incidence of gynaecological cancer

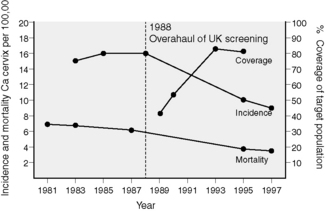

The incidence of gynaecological cancer in England in 2007 is shown in Table 27.1. The incidence of cervical cancer has declined markedly over the last 40 years. This falling trend has been accelerated by the success of the cervical screening programme (Figure 27.3). However, cervical cancer is the most important female cancer in much of the developing world including south Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and South America. In some parts of the USA and Canada, the incidence of carcinoma of body of uterus is more than double that seen in the UK. This may be associated with the epidemic of obesity in North America.

Table 27.1 Incidence of gynaecological cancer in UK in 2007 (CRUK)

| Site | Number of cases | Incidence per 100 000 |

|---|---|---|

| per annum | women | |

| Vulva | 1120 | 3.6 |

| Cervix | 2828 | 9.1 |

| Body of Uterus | 7214 | 23.2 |

| Ovary | 6537 | 20.9 |

Carcinoma of cervix

Pathology of cervical cancer

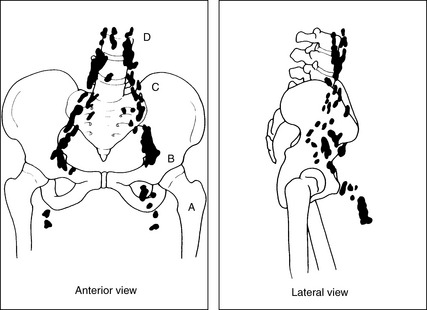

Carcinoma of cervix spreads predominantly by direct invasion and through the lymphatic system. Initially, the tumour spreads into the uterus or vagina and parametrium (the tissues around the uterus). Later, it can infiltrate bladder or rectum. The tumour spreads to the iliac and then para-aortic lymph nodes (Figure 27.4) Blood-borne spread is less common and this may lead to liver, lung and bone metastases.

Symptoms and investigations of cervical cancer

Patients with cervical cancer are staged clinically according to the FIGO staging system (Table 27.2). Accurate staging of cervical cancer is essential so that appropriate treatment can be planned. The cornerstone to staging is an examination under anaesthesia (EUA). The cervix and vagina are inspected and palpated for evidence of tumour. Rectal examination is essential to assess the degree of parametrial spread and to find if the tumour is fixed to the pelvic sidewall. This is usually accompanied by a cystoscopy and, if necessary, a proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy. Patients usually have a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen and pelvis looking for nodal spread and urinary obstruction. MRI scanning is a more effective method for imaging the primary tumour, although spiral CT scanning and MRI are probably equally effective in the evaluation of lymph node metastasis.

Table 27.2 FIGO 2009 staging: carcinoma of the cervix uteri

| Stage I | The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix (extension to the corpus would be disregarded) | |

| Ia | Invasive carcinoma which can be diagnosed only by microscopy. All macroscopically visible lesions, even with superficial invasion, are allotted to Stage Ib carcinomas. Invasion is limited to a measured stromal invasion with a maximal depth of 5.0 mm and a horizontal extension of not >7.0 mm. Depth of invasion should not be >5.0 mm taken from the base of the epithelium of the original tissue, superficial or glandular. The involvement of vascular spaces, venous or lymphatic, should not change the stage allotment | |

| Ia1 | Measured stromal invasion of not >3.0 mm in depth and extension of not >7.0 mm | |

| Ia2 | Measured stromal invasion of >3.0 mm and not >5.0 mm with an extension of not >7.0 mm | |

| Ib | Clinically visible lesions limited to the cervix uteri or preclinical cancers greater than stage 1a | |

| Ib1 | Clinically visible lesions not >4.0 cm | |

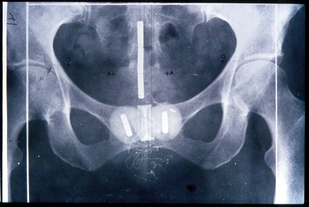

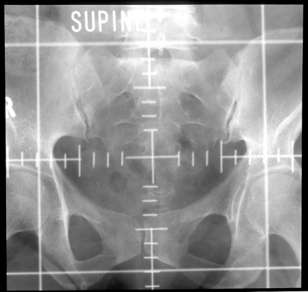

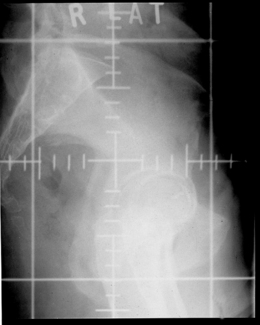

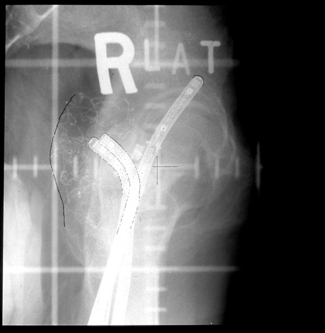

| Ib2 (Figures 27.5 and 27.6) | Clinically visible lesions >4.0 cm | |

| Stage II | Cervical carcinoma invades beyond the uterus, but not to the pelvic wall or to the lower third of the vagina | |

| IIa | No obvious parametrial involvement | |

| IIa1 | Clinically visible lesion ≤4.0 cm in greatest dimension | |

| IIa2 | Clinically visible lesion >4 cm in greatest dimension | |

| IIb (Figures 27.7 and 27.8) | Obvious parametrial involvement | |

| Stage III | The carcinoma has extended to the pelvic wall. On rectal examination, there is no cancer-free space between the tumour and the pelvic wall. The tumour involves the lower-third of the vagina. All cases with hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney are included, unless they are known to be due to other causes | |

| IIIa | Tumour involves lower-third of the vagina, with no extension to the pelvic wall | |

| IIIb (Figures 27.9 and 27.10) | Extension to the pelvic wall and/or hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney | |

| Stage IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis, or has involved (biopsy-proven) the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. A bullous oedema, as such, does not permit a case to be allotted to stage IV | |

| IVa (Figure 27.11 and Figure evolve 27.12 | Spread of the growth to adjacent organs | |

| IVb (Figure 27.13) | Spread to distant organs |

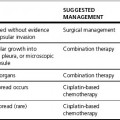

Treatment

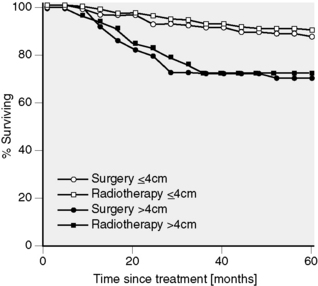

Stage is the most important factor related to outcome. However, tumour size is also an important prognostic feature. It is noteworthy that the survival figures in Table 27.3 relate to patients treated by radical surgery or radiotherapy rather than chemoradiotherapy, as combination treatment has only been given on a wide scale after 1999.

Table 27.3 Carcinoma of the cervix. Patients treated in 1990–92. Survival by FIGO stage (n = 11 945)

| Stage | Patients (n) | Overall 5-year survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ia1 | 518 | 95.1 |

| Ib2 | 384 | 94.9 |

| Ib | 4657 | 80.1 |

| IIa | 813 | 66.3 |

| IIb | 2251 | 63.5 |

| IIIa | 180 | 33.3 |

| IIIb | 2350 | 38.7 |

| IVa | 294 | 17.1 |

| IVb | 198 | 9.4 |

Treatment of stage I disease

The only large randomized trial of radiotherapy and surgery in operable cervical cancer showed equally good results for both modalities (Figure 27.14). The number of serious complications was higher in the surgical arm. However, complications of surgery are usually easier to rectify than the complications of radiotherapy.