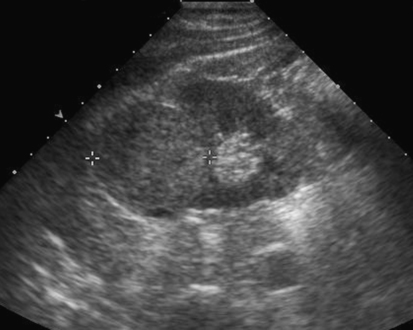

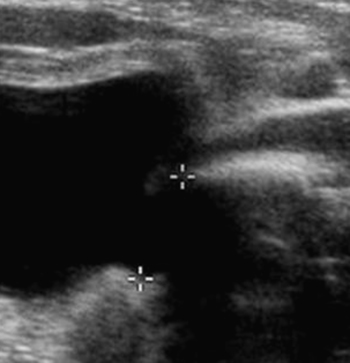

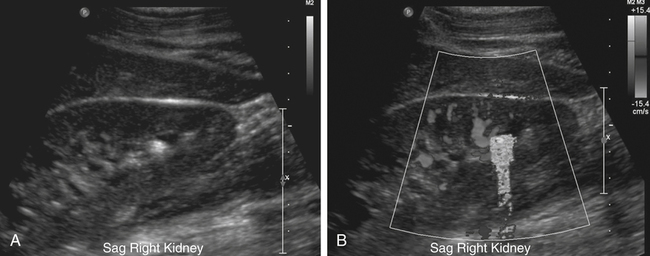

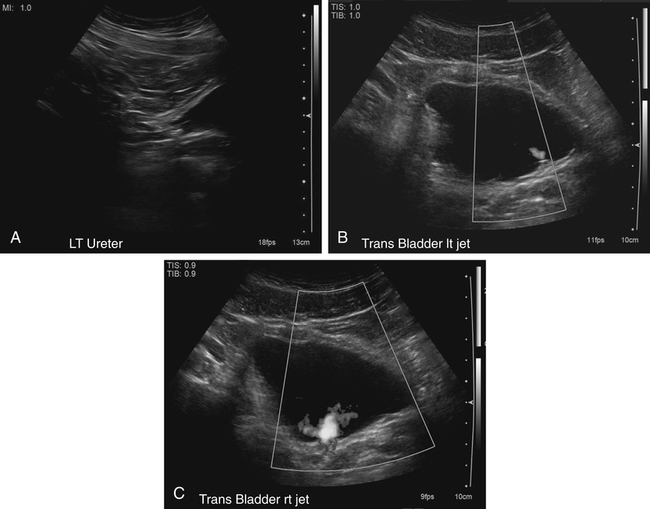

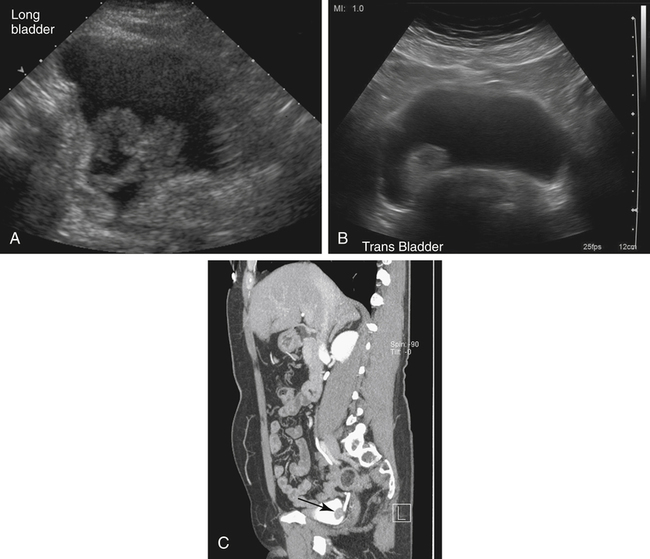

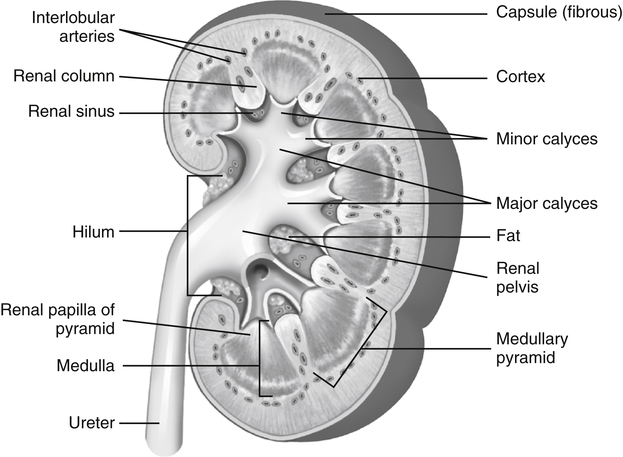

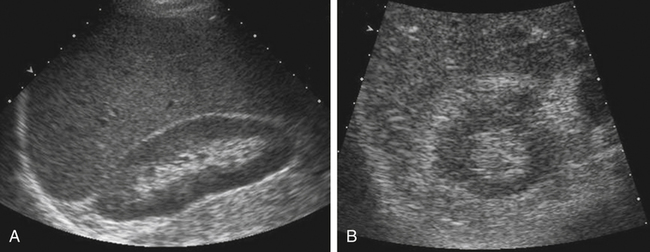

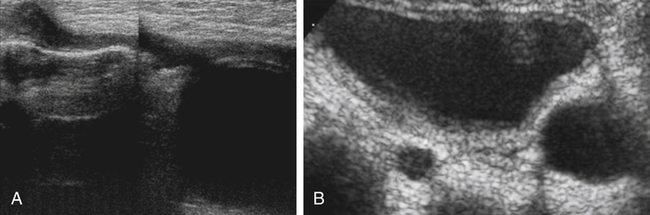

Kerry Weinberg and Kathryn Kuntz • Describe the sonographic appearance of the genitourinary system. • List the causes of hematuria. • Describe the sonographic appearance of urolithiasis. • Describe the sonographic appearance of common benign neoplasms of the kidney. • Describe the sonographic appearance of common malignant neoplasms of the kidney. • Describe the clinical signs and symptoms and laboratory tests associated with hematuria. Hematuria is often the first sign of a urinary tract problem. The cause of hematuria may be anywhere within the urinary system (kidney, ureters, bladder, or urethra) or outside the urinary system (enlarged prostate or gynecologic problem). The amount of blood in the urine can vary from gross (visible) hematuria to microscopic hematuria. Problems of the lower urinary tract (i.e., ureter or bladder) are more likely to have gross hematuria than are problems of the upper urinary tract (i.e., kidney). Patients presenting with gross hematuria are at a higher risk of having a malignancy than patients with microscopic hematuria.1 Hematuria is a nonspecific finding, and the most common causes are acute infection (see Chapter 6), stones within the urinary tract, or tumor. Other, less common causes include trauma, congenital anomaly, renal vein thrombosis, renal cysts, renal infarction, sickle cell disease, enlarged prostate (see Chapter 30), and bleeding disorders, or the cause may be unknown or undetected. In children, blunt or penetrating trauma is the most common cause of urinary tract injury. Hematuria in children may also be caused by nephroblastomas (see Chapter 9). In most cases of microscopic hematuria, imaging is not necessary unless there are associated injuries. Urinalysis is performed to confirm the presence of blood in the urine. A culture may also be performed to detect whether bacteria or tumor cells are present in the urine. Patients who are at high risk for significant renal disease have a history of smoking, have a history of occupational exposure to toxic chemicals and dyes, are older than age 40, have had prior urinary tract infections or symptoms of irritative voiding, or have had prior urinary tract disease. Patients who have abused analgesics or have had pelvic irradiation are also at a higher risk for microscopic hematuria. When hematuria is detected, a urologic consultation, cystoscopy, intravenous pyelogram (IVP) or excretory urography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), renal sonographic examination, or transurethral sonography may be performed to determine the pathology. The use of three-dimensional sonography and three-dimensional contrast-enhanced sonographic examinations has shown promise in differentiating between noninvasive and invasive tumors, especially in the case of bladder tumors.2 This chapter presents some conditions responsible for hematuria that can be evaluated sonographically. The inner anatomy of the kidney consists of the following three distinct sections: the renal parenchyma (cortex), medullary pyramids (which collect and transport urine to the collecting system), and renal sinus (which contains the collecting system, vessels, fat, and lymphatic tissue) (Fig. 5-2). Sonographically, the renal sinus is the echogenic oval region in the midportion of the kidney, the renal cortex has a midlevel echogenicity, and the medullary pyramids are less echogenic than the cortex. When the renal cortex is compared with the liver, it is hypoechoic (Fig. 5-3). The ureters are not usually imaged on a sonogram unless they are dilated. The ureters exit from the medial aspect of the kidneys and follow a vertical course anterior to the psoas muscle to the posterior-lateral aspect of the urinary bladder. When the ureter is dilated, it appears as a linear anechoic or sonolucent structure on a sagittal view (Fig. 5-4) and a round anechoic structure on a transverse view. The urinary bladder is visualized only when it is distended, and then it appears as a fluid-filled, anechoic, thin-walled, symmetric structure. Reverberations may be seen in the anterior portion of the fluid-filled urinary bladder. The urethra is a tubular structure that extends from the base of the urinary bladder to the outside of the body. The urethra in women is much shorter than in men. It is typically not imaged unless an obstruction exists at the urethral level. With sonographic imaging, the urethra appears as a short anechoic or sonolucent tubular structure (Fig. 5-5). Calculi appear sonographically as crescent-shaped, echogenic foci. The presence of posterior acoustic shadowing varies according to the size and composition of the stone. Very small stones may not have posterior acoustic shadowing, or shadowing may be difficult to demonstrate (Fig. 5-6, A). The use of tissue harmonics when small calculi are suspected increases the chance of seeing posterior acoustic shadowing. A color Doppler artifact, the twinkle sign (Fig 5-6, B; see Color Plate 7), may be seen with small stones and may be helpful when shadowing cannot be demonstrated. When seen, this artifact appears as rapidly changing color with a comet tail posterior to the stone. A calculus in the kidney may cause obstructive hydronephrosis (see Chapter 6). Stones that pass into the ureter may obstruct it, leading to ureteral dilation proximal to the site of the obstruction. A stone that causes a complete unilateral obstruction results in absence of a ureteral jet on the affected side (Fig. 5-7, A). A stone causing a partial ureteral obstruction may cause a weak ureteral jet (Fig. 5-7, B) or powerful jets of urine flow into the bladder, which has a color Doppler pattern that resembles a burning candle (candle sign) (Fig. 5-7, C). The sonographic appearance of bladder cancer varies and may have the same echogenicity as a benign neoplasm. Malignant neoplasms tend to appear as an echogenic, irregularly shaped mass projecting into the bladder lumen (Fig. 5-8). Hypervascular bladder wall thickness may also be present. The use of three-dimensional ultrasound imaging increases the distinction of the layers of the bladder wall to differentiate between noninvasive and invasive tumors.3 Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is also referred to as hypernephroma or adenocarcinoma. RCC accounts for most clinically relevant renal tumors. There is a significant predominance of men over women, with peak incidence occurring between age 60 and 70.4 Etiologic factors include lifestyle factors, such as smoking, obesity, and hypertension. Cigarette smoking is a definite risk factor for RCC. The roles of obesity and hypertension as risk factors for RCC have not been as definitively clarified. Chemical exposure (e.g., asbestos, cadmium), long-term kidney dialysis, and von Hippel-Lindau disease are also linked to the development of RCC. Some patients with RCC have hematuria. Other clinical signs include a palpable mass, flank pain, weight loss, fever, or hypertension. Because of the increased detection of tumors with the use of imaging, a growing number of incidentally diagnosed RCCs are found. These tumors are more often smaller and of lower stage. Today, more than 50% of RCCs are detected incidentally using noninvasive imaging for the evaluation of various nonspecific symptoms.4 The previously reported classic triad of flank pain, gross hematuria, and palpable abdominal mass is now rarely found. In addition, abnormal laboratory findings may be seen, such as erythropoietin blood level; red blood cells, white blood cells, and bacteria in the urine; and elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels. The tumor may spread throughout the kidney and perinephric fat, invade the renal vein, and travel to the inferior vena cava (IVC). Approximately one-third of patients have metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Metastasis to the regional lymph nodes, lungs, bone, contralateral kidney, liver, adrenal glands, and brain may occur. At the time of diagnosis, a very small percentage of RCCs are bilateral. Prognosis depends on the stage of the disease at diagnosis. RCCs can be staged using the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM (tumor, node, metastases) classification, as follows: • Stage 1 RCCs are 7 cm or smaller and confined to the kidney. • Stage 2 RCCs are larger than 7 cm but still confined to the kidney. • Stage 3 tumors extend into the renal vein or vena cava, involve the ipsilateral adrenal gland or perinephric fat or both, or have spread to one local lymph node. • Stage 4 tumors extend beyond Gerota’s fascia to more than one local node or have distant metastases.

Hematuria

Genitourinary System

Normal Sonographic Anatomy

Urolithiasis

Nephrolithiasis

Sonographic Findings

Bladder Neoplasms

Sonographic Findings

Malignant Neoplasms

Renal Cell Carcinoma

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine