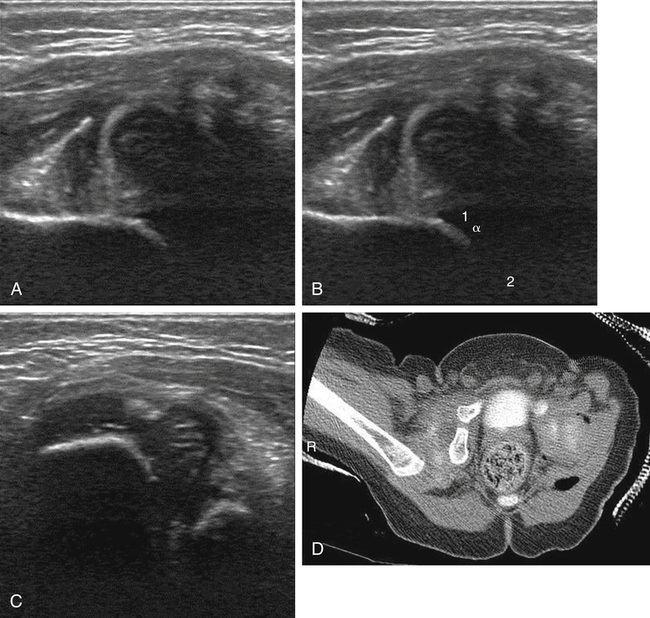

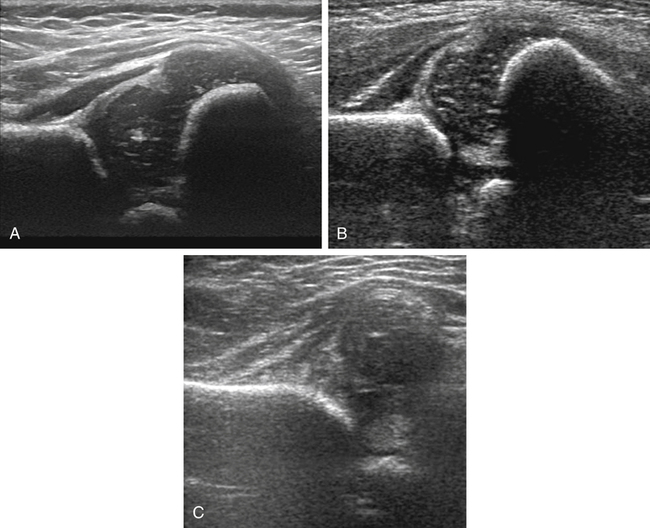

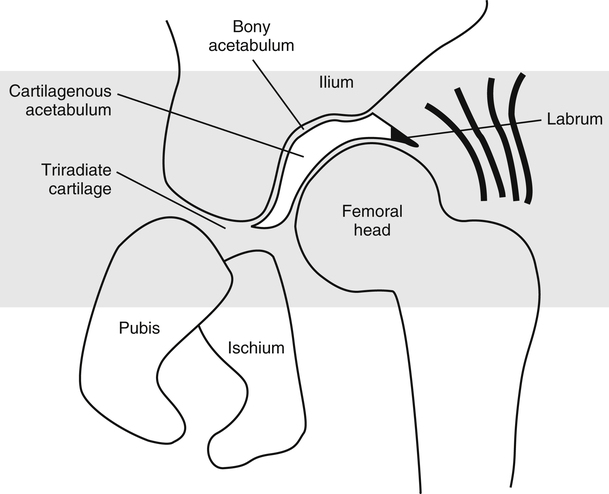

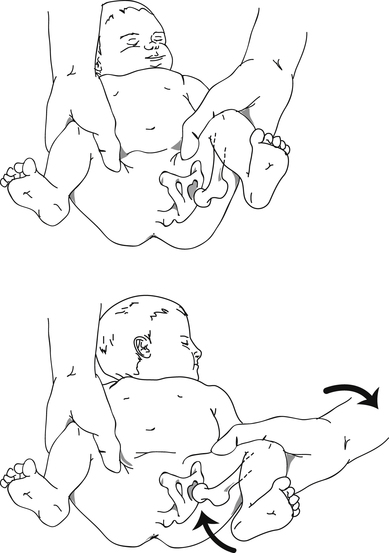

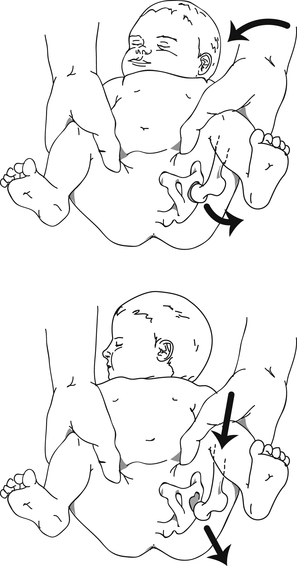

The hip comprises the femoral head and the acetabulum. The femoral head is cartilaginous at birth and begins to ossify between 2 and 8 months, with ossification occurring earlier in girls. The acetabulum comprises cartilage and bone. The bony acetabulum (Fig. 31-2) consists of the ilium, the ischium, and the pubis, which is joined by a growth plate known as the triradiate cartilage. The cartilaginous labrum is located at the acetabular rim and extends over the superolateral aspect of the femoral head. DDH describes a spectrum of abnormalities that involve an abnormal relationship of the femoral head to the acetabulum, which includes mild instability, subluxation, and frank dislocation. DDH also has been referred to as congenital hip dysplasia, although this is a misnomer because hip dysplasia may develop after birth. The incidence varies depending on whether or not the neonatal population is routinely screened, with a higher incidence in the screened population. In the United States, the incidence is 1.5:1000 to 15:1000 live births.1 There is also geographic and ethnic variability that may be secondary to environmental or genetic factors or both. An example of this variability is the lower incidence in native Africans versus African Americans; however, the incidence is lower in African Americans compared with the overall prevalence of DDH in the United States.1 Hip instability is associated with joint laxity and may be identified in newborns affected by maternal hormones. This laxity often resolves within the first few weeks of birth and necessitates no treatment. Unless there is a significant instability or dislocation, sonographic evaluation of the infant hip is not recommended before 3 to 4 weeks of age to avoid overtreatment in populations in whom the instability would spontaneously resolve.2 Subluxation of the hip refers to a femoral head that is shallow in location, allowing it to glide within the confines of the acetabulum. Hip dislocation is defined as a femoral head that is located outside of the acetabulum and may be reducible or irreducible. Hip dislocation can also be associated with congenital neurologic or musculoskeletal anomalies, including spina bifida, scoliosis, arthrogryposis, talipes, and numerous syndromes, and is referred to as teratologic hips.1,2 Many risk factors associated with DDH are related to the inability of the fetus or newborn to move freely. These conditions include pregnancies affected by oligohydramnios (including serious renal anomalies), breech presentation, first pregnancy (primigravida), high birth weight, and postmaturity. Other infants at risk include infants born in the cold seasons of the year, female infants, and infants with torticollis. There is an increase in infants born where swaddling is prevalent, including in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Japan as well as Navajo Indians.1 The left hip is affected more commonly than the right, and DDH is bilateral in 20% of cases.1 Family history is also an important factor in identification of infants at risk for development of DDH, especially when parents or siblings are affected. Evaluation for hip dysplasia is part of every newborn examination. The accuracy of the evaluation is affected by the experience of the physician. Infants in whom hip dysplasia does not develop until after birth may initially have a normal examination. Clinical findings associated with DDH include asymmetric skin folds of the thighs and one knee appearing lower than the other when the hips and knees are flexed. The subluxed or dislocated hip appears shorter (known as the Galeazzi or Allis sign). Also, limited abduction of the hip may be observed.3 Clinical maneuvers also can be used to detect hip instability and dislocation, but performance of these maneuvers may be difficult if the infant is not relaxed and are best performed in a warm room after feeding. The two maneuvers are performed with the infant’s hips and knees flexed, and one hip should be examined at a time. The Ortolani maneuver (Fig. 31-3) involves abduction of the thigh while the hip is gently pulled anteriorly. If the hip is dislocated, the hip may relocate into the acetabulum with a palpable (and possibly audible) “click.” The Barlow maneuver (Fig. 31-4) is performed with adduction of the hip with a gentle posterior push in an effort to solicit subluxation or dislocation in an abnormal hip.3 These maneuvers are similar to maneuvers performed in a dynamic sonographic evaluation. The technique for imaging the infant hip was initially described by Graf, who used a static approach. Harcke developed a dynamic approach to sonographic imaging. The two approaches were combined to develop a minimum standard examination.4 The imaging protocol should incorporate two orthogonal views with one view that includes stress views; this typically includes the coronal/neutral or coronal/flexion view and the transverse/flexion view. Additional views, including anterior views, and measurements are considered optional, although they may be dictated by institutional protocol.4 Particular care should be taken to image each view in the correct plane and with the appropriate anatomy identified because a minimal shift in the image may lead to an inaccurate diagnosis. This chapter defines the images for the minimum standard examination and describes normal and abnormal findings. The coronal/neutral view of the hip is obtained with placement of the transducer in a coronal plane at the lateral aspect of the hip. The hip is maintained in a physiologic neutral position with approximately 15 to 20 degrees of flexion. By slightly rotating the superior aspect of the transducer posteriorly, the image should demonstrate the midportion of the acetabulum, with the ilium appearing as a straight line parallel to the transducer. The junction of the ilium and triradiate cartilage should be clearly identified, and the cartilaginous tip of the labrum should be visualized.2 The femoral metaphysis is also seen in this plane, which differentiates this view from the coronal/flexion view. A normal hip (Fig. 31-5, A) shows the hypoechoic femoral head resting against the acetabulum. An abnormal hip (Fig. 31-5, B) migrates laterally and superiorly.

Hip Dysplasia

Anatomy of the Hip

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Risk Factors

Clinical Evaluation

Sonographic Evaluation of Infant Hips

Coronal/Neutral View

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Hip Dysplasia