, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

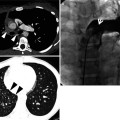

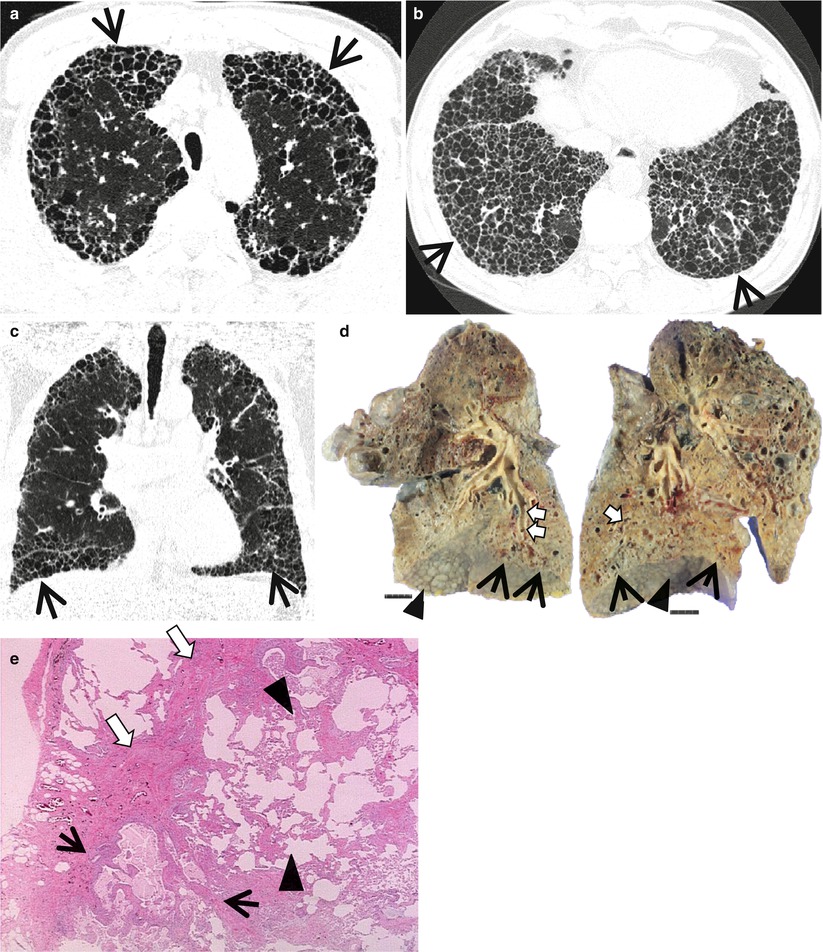

Pathologically, honeycombing (HC) represents destroyed and fibrotic lung tissue containing numerous cystic airspaces with thick fibrous walls [1] (Fig. 17.1). In addition, HC on pathology is characterized by cysts usually measuring <1 mm, often below the resolution of CT, and therefore not necessarily concordant with macroscopic HC seen on CT images. On thin-section CT (TSCT) scans, the appearance is of clustered cystic air spaces, typically of comparable diameters on the order of 3–10 mm but occasionally as large as 25 mm [2] (Fig. 17.1b). Some researchers may consider HC as a multilayer cluster of cysts with shared walls, but others may recognize a single layer cluster of cysts [3] (Fig. 17.1c).

Honeycombing with Subpleural or Basal Predominance

Definition

Pathologically, honeycombing (HC) represents destroyed and fibrotic lung tissue containing numerous cystic airspaces with thick fibrous walls [1] (Fig. 17.1). In addition, HC on pathology is characterized by cysts usually measuring <1 mm, often below the resolution of CT, and therefore not necessarily concordant with macroscopic HC seen on CT images. On thin-section CT (TSCT) scans, the appearance is of clustered cystic air spaces, typically of comparable diameters on the order of 3–10 mm but occasionally as large as 25 mm [2] (Fig. 17.1b). Some researchers may consider HC as a multilayer cluster of cysts with shared walls, but others may recognize a single layer cluster of cysts [3] (Fig. 17.1c).

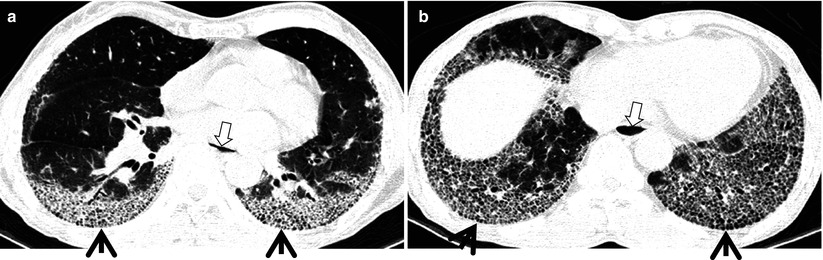

Fig. 17.1

Typical honeycomb cysts in a 50-year-old man with usual interstitial pneumonia. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of aortic arch (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show back-to-back cysts (arrows) in subpleural regions of both lungs. Cysts are at least two layers or more in both lungs. (c) Coronal reformatted image (2.0-mm section thickness) demonstrates subpleural honeycomb cysts (arrows) in both lungs. (d) Explanted lungs from a different patient who suffered from acute exacerbation of usual interstitial pneumonia depict consolidative lower lobes (arrowheads) through which honeycomb cysts (arrows) are visualized. Also note traction bronchiectasis (open arrows). (e) High-magnification (× 200) photomicrograph discloses combined findings of honeycomb cysts filled with mucus (arrows), interstitial fibrosis (open arrows), and inflammatory cell infiltration (arrowheads)

Diseases Causing the Pattern

Cystic structures of HC on transverse CT images consist of either dilated peripheral bronchioles or alveolar ducts, surrounded by several in-folded layers of thickened alveolar septa (a true HC cyst) or tangential view of traction bronchiectasis (TB). In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) (Figs. 17.1 and 17.2), cystic structures are mainly composed of true HC cysts in the peripheral portion of the lungs, while most cystic structures in patients with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) (Fig. 17.3) seem to be tangential views of TB [4]. Of course, even in patients with NSIP, main cysts of HC are the true HC cysts as in IPF/UIP. Honeycombing has been reported in up to 40 % of NSIP [5]. HC may be observed in approximately 10 % of patients with asbestosis (Fig. 17.4) along with findings of irregular interlobular septal thickening, intralobular interstitial thickening, subpleural dot-like or branching opacity, and ground-glass opacity (GGO), not to mention of pleural plaques [6].

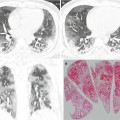

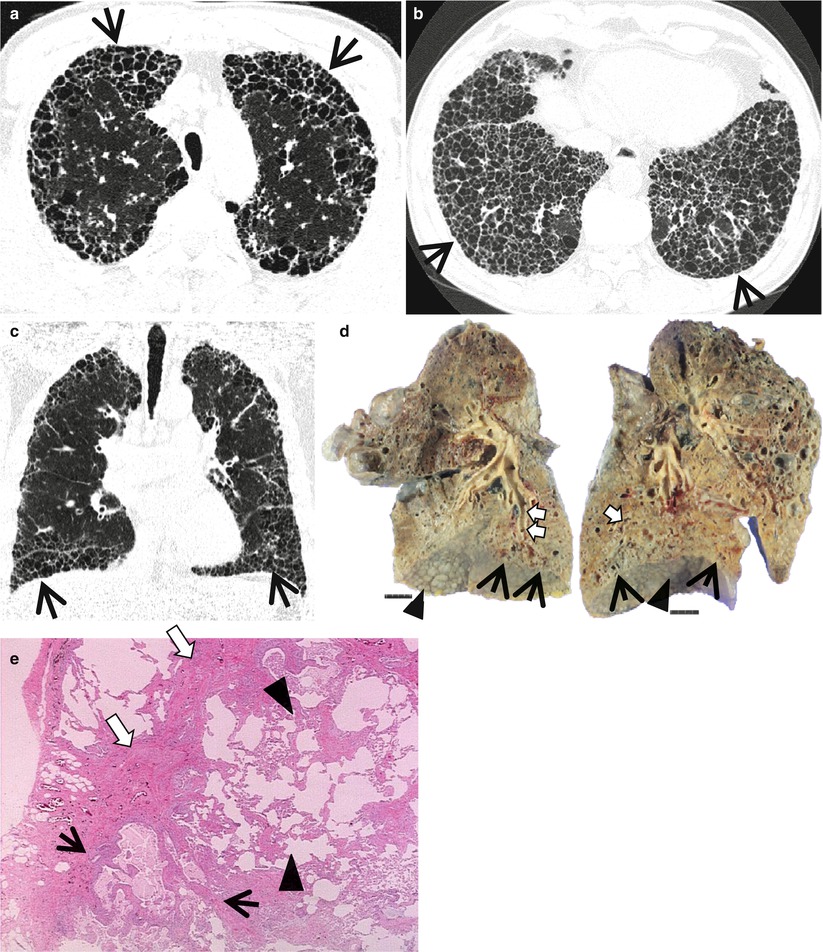

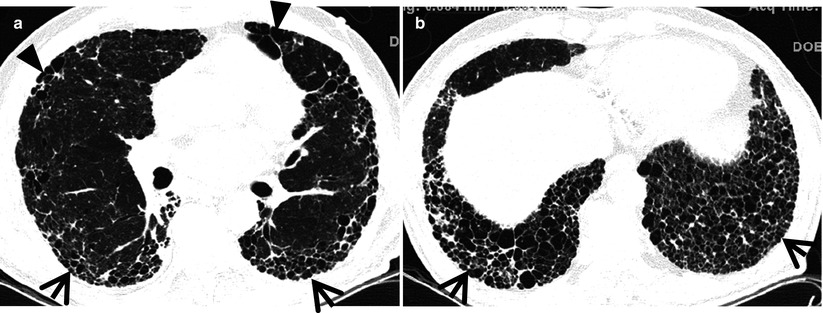

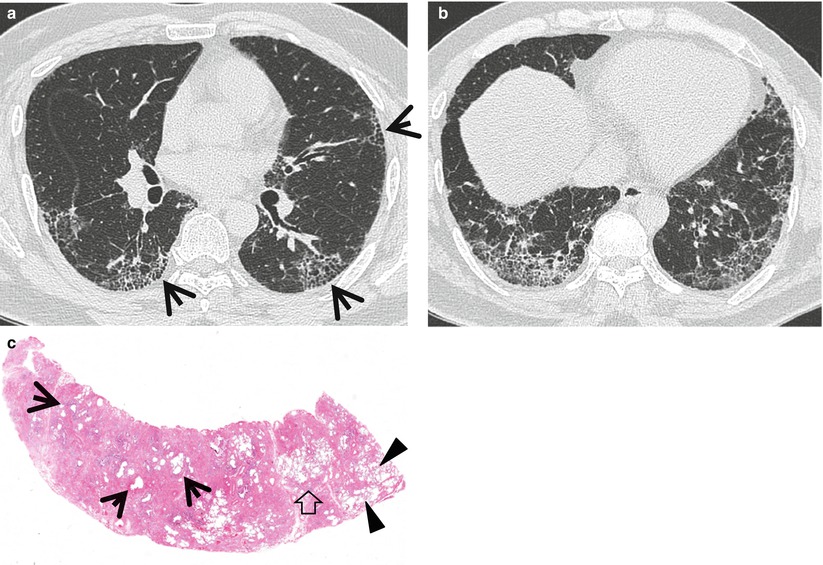

Fig. 17.2

Typical honeycomb cysts in a 58-year-old man with usual interstitial pneumonia. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of distal bronchus intermedius (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show back-to-back cysts (arrows) in subpleural regions of both lungs. Most cysts are at least two layers or more in both lungs. Also note some areas of pulmonary emphysema (arrowheads) in anterior lungs of the middle lung zones

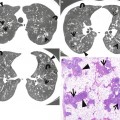

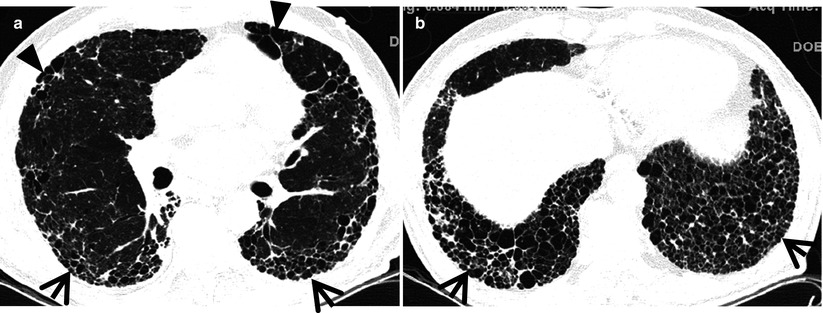

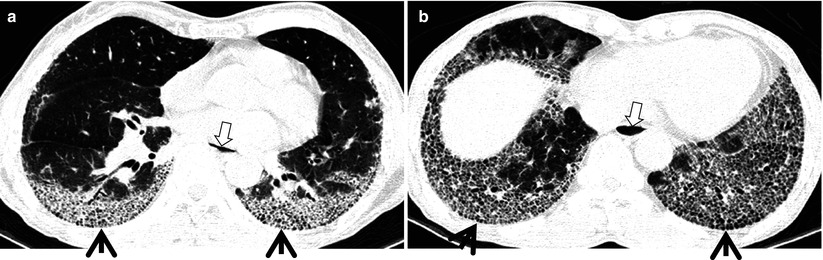

Fig. 17.3

Honeycomb cysts in a 67-year-old woman with progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS)-associated nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of inferior pulmonary veins (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show honeycomb cysts (arrows) seen through ground-glass opacity in bilateral lower lung zones. Patient had acute exacerbation of pulmonary fibrosis and, thus, had accompanying ground-glass opacity with background honeycomb cysts. Also note distal esophageal dilatation with air filling (open arrows) owing to esophageal involvement of PSS

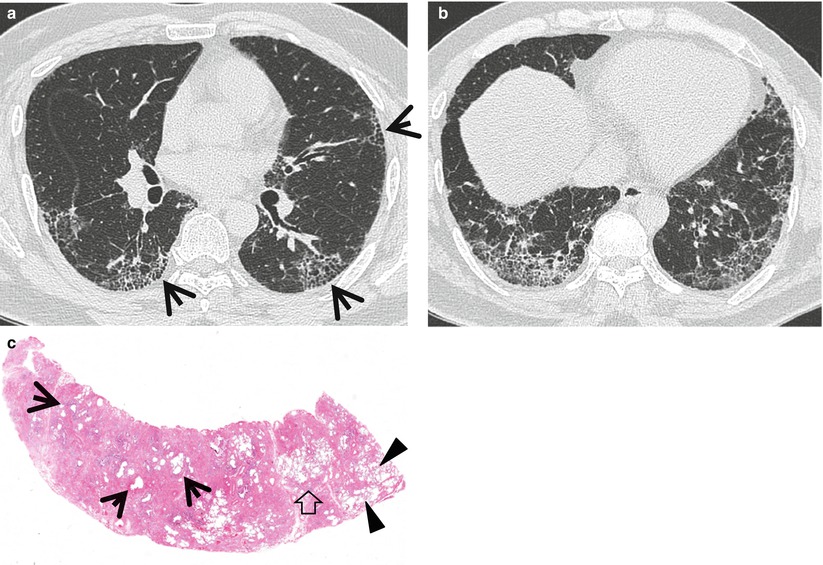

Fig. 17.4

Honeycomb cysts in a 39-year-old man with asbestosis who is working in a building demolition place. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.5-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of right middle lobar bronchus (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show reticulation and ground-glass opacity in subpleural regions of lower lung zones. Also note scattered areas of honeycomb cysts (arrows). (c) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen obtained from right lower lobe discloses pulmonary fibrosis of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern with large area of irregular interstitial fibrosis including microscopic honeycombing (arrows), few areas of chronic inflammatory cell infiltration (open arrow), and normal lung areas (arrowheads)

Distribution

In most diseases, lung abnormalities show lower lung zone and subpleural-distribution predominance. In NSIP, abnormalities may be located along the bronchovascular bundles and may demonstrate subpleural sparing [7].

Clinical Considerations

The identification of HC is essential for making the certain CT diagnosis of UIP and for predicting patient prognosis with fibrotic IIPs [8].

Even in cases of fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) with little HC, serial CT reveals an increase in the extent of HC and reticulation and a decrease in the extent of GGO. Overall extent of lung fibrosis on the baseline CT examination appears predictive of survival in fibrotic IIPs with little HC [9].

Measuring a fibrotic score (the extent of reticulation plus HC) at TSCT helps predict patient prognosis. In other words, patients with UIP or fibrotic NSIP who have a high fibrotic score determined at thin-section CT and a low DLco level have a high death risk [10].

HC mimickers at CT are paraseptal emphysema and TB of varying severity. NSIP may simulate UIP at CT in the presence of emphysema [11]. Any fibrotic interstitial pneumonia with concurrent emphysema may cause problems in CT interpretation [12].

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

Diseases | Distribution | Clinical presentations | Others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zones | ||||||||||||

U | M | L | SP | C | R | BV | R | Acute | Subacute | Chronic | ||

IPF/UIP | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

NSIP | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | Female predominance; subpleural sparing and along BV bundles | |||

Asbestosis | + | + | + | + | + | Exposure history and pleural plaques; with subpleural dot-like or branching opacity and subpleural lines | ||||||

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis/Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

In a typical case, the lungs are shrunken and firm when removed at autopsy or explanted. The lower lobes are most severely affected, with the pleura having a finely nodular “cobblestone” pattern, resembling that of a cirrhotic liver. Pleural fibrosis is uncommon, in contrast to asbestosis. The cut surface of the lung shows fibrosis and a variable degree of “honeycombing,” which is most marked beneath the pleura (Fig. 17.1). The cardinal features of UIP are subpleural and paraseptal predominance, patchy parenchymal involvement, fibrosis leading to loss of architecture, fibroblastic foci adjacent to the established fibrosis indicative of progressive disease, only mild to moderate chronic interstitial inflammation, and an absence of any causal feature such as inorganic dust, granulomas, or accumulations of Langerhans cells [13].

Symptoms and Signs

IPF occurs in middle-aged and elderly adults (median age at diagnosis 66 years, range 55–75 years) [14]. Dry cough and slowly progressive dyspnea on exertion are the cardinal symptoms of IPF. Systemic symptoms, such as fever and weight loss, are rare. Patients may be asymptomatic at the early stage of IPF. Finger clubbing is found in more than 50 % of the patients. Bibasilar fine inspiratory crackle, so-called Velcro-like rale, is heard on chest auscultation.

CT Findings

The characteristic HRCT findings of UIP consist of intralobular lines and honeycombing involving mainly the subpleural regions and lung bases [15] (Figs. 17.1 and 17.2). The intralobular interstitial thickening also results in the presence of irregular interfaces between the lung and pulmonary vessels, bronchi, and pleural surfaces. The bronchioles and bronchi in the areas of fibrosis are often dilated and tortuous (traction bronchiolectasis and bronchiectasis). Parenchymal involvement is typically patchy on HRCT, with areas of normal and markedly abnormal lung often present in the same lobe. Other findings of UIP on HRCT include irregular thickening of interlobular septa and patchy areas of GGO. On HRCT, the overall extent of fibrosis (reticulation and honeycombing) has been consistently shown to correlate with disease severity parameters on pulmonary function tests and prognosis [10]. Recently, the extent of honeycombing at baseline as well as its progression on sequential follow-up CT scan is demonstrated as an important prognostic determinant in patients of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia, including UIP and fibrotic NSIP [9].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Histologically, UIP shows a variable degree of interstitial inflammation and fibrosis [13]. As disease becomes more severe, alveoli are replaced by fibrous tissue. Contraction of this tissue results in the dilatation of respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts, leading to the formation of honeycombing cysts. The intralobular lines reflect the presence of interstitial fibrosis. Interlobular septal thickening reflects the presence of fibrosis in the periphery of the secondary lobules and patchy areas of GGO reflects areas of inflammation or fibrosis. Patchy parenchymal involvement on HRCT reflects histologic features of heterogeneous appearance in which areas of fibrosis with scarring and honeycombing alternate with areas of less affected or normal parenchyma.

Patient Prognosis

IPF is a chronic, progressive, irreversible, and usually fatal lung disease. There is no therapy proven to be effective [16]. Median survival has been reported to be 2–5 years. Lung transplantation remains the last therapeutic option.

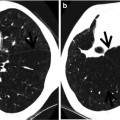

Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

It is a uniform-appearing, cellular interstitial pneumonia characterized by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the alveolar septa. Varying amounts of fibrosis consisting predominantly of collagen are admixed with the chronic inflammation, and cases can be divided into cellular and fibrotic variants. Patchy intra-alveolar macrophage accumulation and small foci of intraluminal fibrosis resembling BOOP may occur but are always overshadowed by the more extensive interstitial pneumonia [17].

Symptoms and Signs

Cough and dyspnea are the most common symptoms in patients with idiopathic NSIP [14]. The duration of respiratory symptoms is around 6 months, which is shorter than in IPF. Median age of NSIP is 52 years (range 26–73). Finger clubbing can be observed but is less frequent than in IPF.

CT Findings

The most common HRCT findings of NSIP consist of lower lobe, peripherally predominant, and GGO with reticular abnormality, traction bronchiectasis, and lower lobe volume loss [5]. Honeycombing and consolidation are relatively uncommon. The reported prevalence of honeycombing ranges from 0 to 44 % (Fig. 17.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree