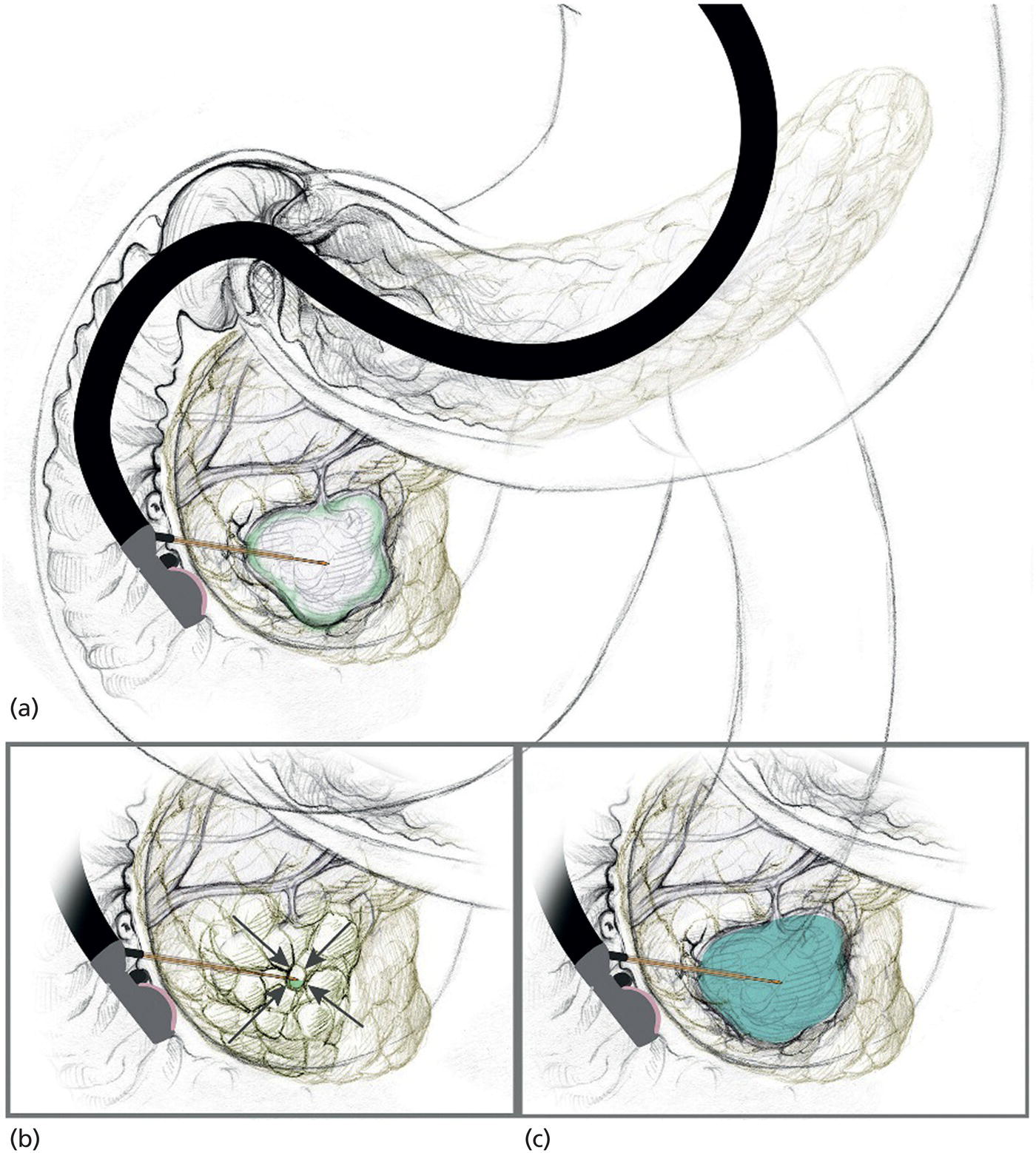

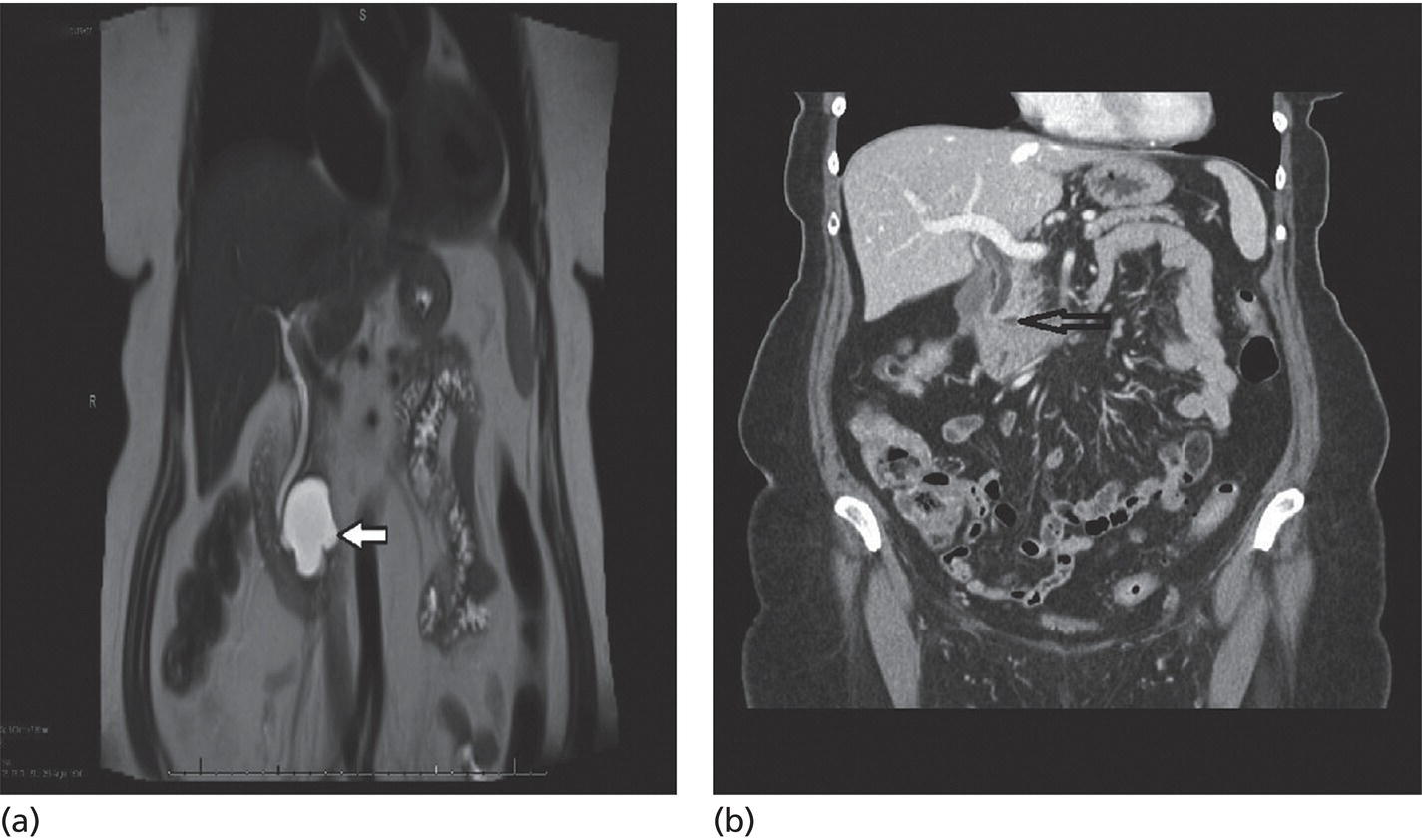

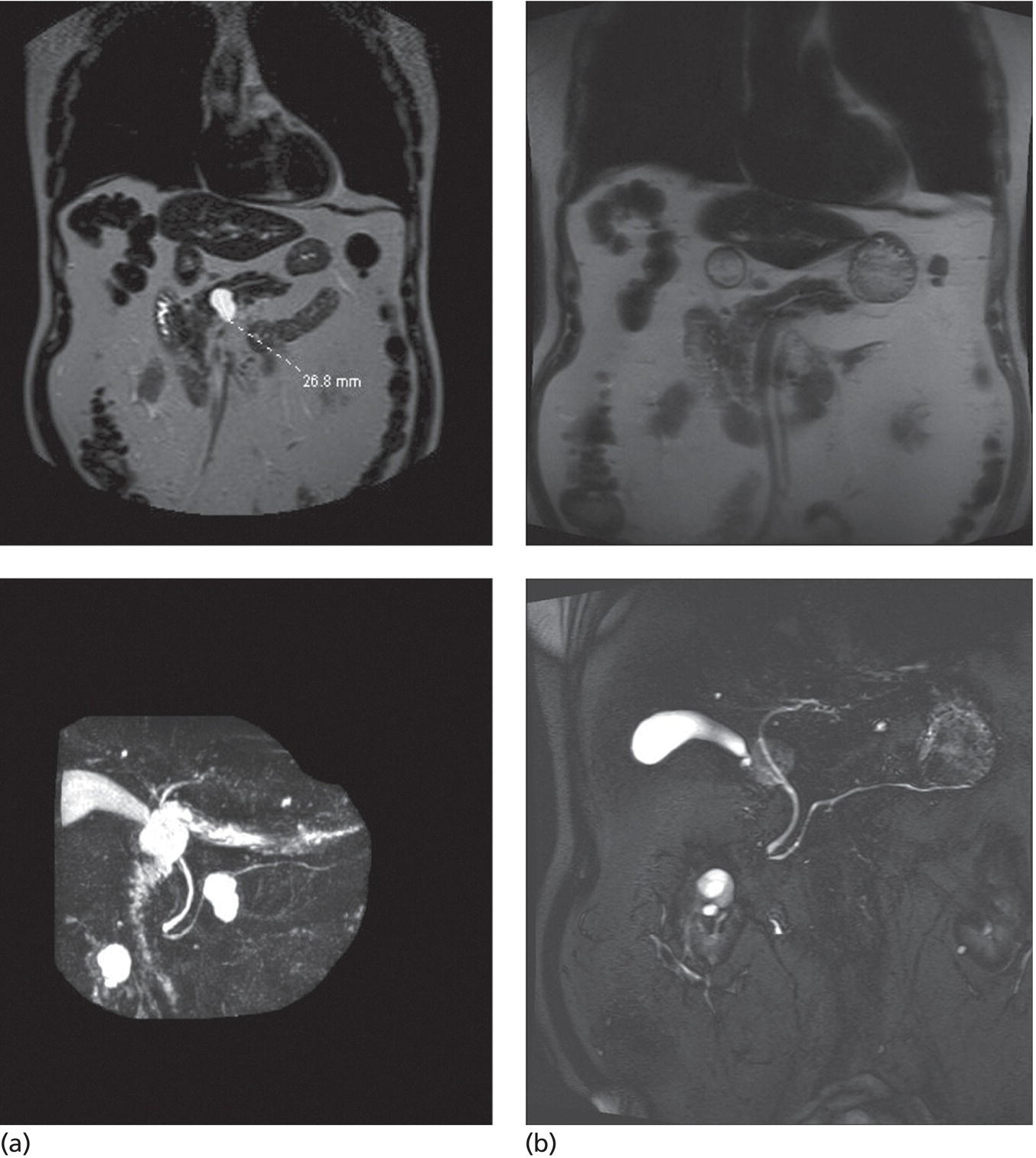

Matthew T. Moyer1 and John M. DeWitt2 1 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA, USA 2 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Indiana University Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN, USA Few areas in medicine are as controversial as the diagnosis and management of mucinous‐type pancreatic cysts. Guidelines on the subject are often discordant and based on expert opinion, with the 2017 Fukuoka and 2018 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines the most recent and generally the most widely accepted [1,2]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)‐guided pancreatic cyst chemoablation is a promising, rapidly evolving, and minimally invasive approach for the treatment of mucinous‐type pancreatic cysts. Here, we present a clinical and technical review of EUS‐guided ablationE with our recommendations on the indications, contraindications, and appropriate patient selection, and a technical review of the performance of the procedure as well as follow‐up. A lethal malignancy, pancreatic cancer carries a dismal five‐year survival rate of 8% and has the lowest survival rate of any major cancer. It is projected to surpass colorectal cancer as the second‐leading cause of cancer‐related death by 2030 unless breakthroughs in prevention and therapy occur, as we have seen in colorectal cancer [3–5]. The etiology of approximately 80% of pancreatic cancer is ductal adenocarcinoma; however, at least 20% of pancreatic cancer stems from the progressive degeneration of mucinous‐type pancreatic cysts [6]. Occurring in over 2% of US adults overall, the prevalence of pancreatic cysts has grown dramatically over the last 20 years due to an aging population and advances in imaging techniques, leading to a public health dilemma. The majority of pancreatic cysts are neoplastic and include mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) which carry significant potential for malignant transformation [4]. The overall risk of progression to malignancy for a mucinous cyst ranges from 1 to over 50% and is generally linked to its number of high‐risk features, per consensus criteria [1,2]. Identification of a mucinous pancreatic cyst requires the patient and clinician to choose between indefinite radiographic surveillance by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or surgical resection, both of which have considerable limitations. Radiographic surveillance is nontherapeutic and carries significant financial and psychological burdens, while surgical resection poses a substantial risk for serious adverse events (20–40%) and mortality (1–5%). In fact, a recent randomized controlled trial showed the mortality of Whipple surgery to be as high as 10%, even in high‐volume centers [7–10]. Moreover; subtotal pancreatectomy still requires postoperative and long‐term surveillance for IPMNs. This clinical dilemma presents a pressing need to develop a minimally invasive but effective and efficient approach for this patient population in desperate need of improved treatment options. In this respect, EUS‐guided pancreatic cyst chemoablation has emerged as an innovative and promising minimally invasive approach for the treatment of pancreatic cysts [11–13]. EUS‐guided pancreatic cyst ablation was first described using cyst lavage with dehydrated alcohol; however, cyst ablation using alcohol lavage alone was hampered by low efficacy and an adverse event rate of 2–24%, generally felt to be due to the inflammatory and toxic effects of the alcohol on pancreatic parenchyma and/or neighboring vessels. Consequently, the use of alcohol lavage alone for cyst ablation has largely been abandoned. The more contemporary approach of cyst ablation involves cyst aspiration followed by three to five minutes of alcohol lavage, followed by near‐complete aspiration and then instillation of paclitaxel 6 mg/ml, which is often partially diluted due its high viscosity. Complete ablation rates using this two‐step technique are reported at 50–79% and this significant increase in efficacy over alcohol alone has resulted in this combination therapy becoming the most widely reported approach for pancreatic cyst ablation over the last 10 years, offering complete ablation rates similar to that seen in other ablative strategies in gastroenterology. However, despite its increased efficacy, a significant limitation of alcohol lavage and paclitaxel injection continues to be serious adverse events of pancreatitis, peritonitis and venous thromboembolism, occurring in up to 10% of patients, again likely due to the potent inflammatory and toxic effects of alcohol on the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma and neighboring vessels. A summary of all studies using a prospective design and employing alcohol or alcohol followed by chemoablation is shown in Table 34.1. In 2017, the randomized, prospective, double‐blind CHARM trial was published, demonstrating the clinical value of a completely alcohol‐free chemoablation approach. In this study, 39 patients were randomized to initial alcohol or saline lavage, with both arms then treated with a chemoablation cocktail tailored specifically for pancreatic neoplasia (38 mg gemcitabine mixed with 6 mg/mL of paclitaxel). At one year, 61% of patients in the alcohol arm achieved complete ablation, compared with 67% in the alcohol‐free arm, showing that alcohol is not required for effective pancreatic cyst ablation when a chemotherapy cocktail specifically designed for pancreatic neoplasia is used. More importantly, the rate of adverse events was significantly lower in the alcohol‐free arm (P = 0.01) with minor adverse events of abdominal pain (22%) and serious adverse events of pancreatitis (6%) both limited to the alcohol arm, collectively showing that the removal of alcohol from pancreatic cyst ablation reduces adverse events to rates similar to those of EUS‐FNA [21]. The results of this randomized clinical trial indicate that an alcohol‐free EUS‐guided ablation approach is an improved therapeutic option for the treatment of mucinous‐type pancreatic cysts and has led to a larger, randomized, prospective, multicenter, National Institutes of Health‐funded trial which incorporates several technical improvements with results expected in the next five years [22]. There have been concerns raised regarding the long‐term durability of pancreatic cyst ablation since the tumor is ablated and not surgically resected [23]. However, in a recent comprehensive evaluation of long‐term efficacy, Choi et al. [24] reported the results of 164 patients who underwent EUS‐guided ablation with ethanol followed by paclitaxel. In this study, 72% of patients achieved complete cyst ablation, and over a six‐year follow‐up period 98% of these remained in complete remission. The authors concluded that this treatment approach is an effective and durable alternative to surgery in appropriately selected patients. It is our recommendation that patients considered for EUS‐guided cyst ablation should undergo a full evaluation in a clinic setting where their clinical, radiographic and endoscopic status can be reviewed in discussion with the clinician. Important issues to discuss are the natural history of these tumors, the rationale, risks and benefits of an ablation strategy, areas of uncertainty, and conventional options of surveillance and/or surgical resection as appropriate. A detailed informed consent is mandatory, and it is the recommendation of a soon‐to‐be published international white paper that these procedures be performed by an interventional endoscopist with formal training in EUS from a credentialed program who is familiar with interventional EUS procedures. Additionally, it is our recommendation that these procedures be performed in a high‐volume referral center in a multidisciplinary environment, with appropriate follow‐up and a formal quality assurance process. In order to be effective, EUS‐guided pancreatic cyst ablation should not be performed on lesions with certain high‐risk features or a high likelihood of malignancy that may impede effective treatment. Conversely, therapy should be avoided in small low‐risk pancreatic cysts with little chance of malignant progression and more appropriate for radiographic surveillance as per guidelines. Ablative strategies should be focused on cystic tumors that are technically amendable to ablation and do not show overt signs of malignancy. Only cysts with a significant likelihood of progression to malignancy can be reasonably considered candidates for ablation. For that reason, the first step in the evaluation is to use clinical, radiographic, cytologic, and chemical analysis from EUS‐FNA to diagnose and risk stratify a mucinous type cyst [25]. High‐quality data indicate that the overall risk of developing malignancy in a pancreatic cyst measuring 1.5 cm or smaller (without other worrisome features) is less than 1% [26]. Additionally, performing effective EUS‐guided cyst ablation in lesions smaller than 1.5 cm is technically difficult, and as the FNA needle itself has a volume of 0.8 ml this prohibits meaningful exchange of chemotherapeutic agent. A minimum size of 2 cm had been previously proposed for surgical resection in patients who are good surgical candidates due to an increased cumulative risk of malignant progression in cystic lesions starting at this size over a patient’s lifetime [27]. Consequently, it is our recommendation that mucinous pancreatic cysts ranging in size from 2 to 6 cm meet appropriate size criteria and are the typical range reported in most trials to date [11–13]. The overall structure of a cyst is also an important consideration because multiseptated mucinous cysts (ex. “cluster of grapes” type IPMN) present a technical challenge to ablation since treatment must reach each discrete loculated chamber within a cyst in order to ensure complete ablation. Thus, most trials to date have favored treatment of unilocular or oligolocular cyst morphology and have avoided ablation in lesions with more than four or five discrete loculations [11–13]. When reviewing previous trials and the experience at our centers, our general recommendations for indications and contraindications for pancreatic cyst ablation can be summarized as follows and used to guide therapy. Table 34.1 Summary of EUS‐guided ablation trials (only studies with a prospective design are included). a Clinically significant adverse events are presented as an aggregate of the two most common (pancreatitis and abdominal pain). Based on the reported results, it cannot be determined if adverseevents overlapped (e.g. a patient who developed pancreatitis also reported abdominal pain). Rare types of adverse events were single events and include peripancreatic fluid collection [19], splenicvein obliteration [19], development of an inflammatory gastric wall cyst [20], and peritonitis [20]. b Note the significant drop in adverse events when alcohol‐free EUS‐guided cyst ablation was used, indicating a significant increase in safety when an alcohol‐free protocol is used. EtOH, ethyl alcohol; RCT, randomized controlled trial. Patients with previously identified pancreatic cysts ranging from 2 to 6 cm in diameter which are consistent with mucinous‐type cysts as per guidelines [25] including indeterminate‐type cysts. Cysts with the following high‐risk features. Patient preparation for pancreatic cyst ablation is similar to that for standard EUS‐FNA. A discussion with the anesthesiologist is important to ensure that the patient will be relatively still during the actual ablation process and if excessive movement (such as coughing or retching) is felt to be likely, general anesthesia with paralysis should be considered. The ablative agents, including a lavage agent (if used), as well as the chemotherapy infusion (i.e. paclitaxel or paclitaxel plus gemcitabine) should be prepared prior to the procedure and laid out with the infusion device for ease of access during the procedure. The delivery, handling, and disposal of chemotherapy ablation agents should be standardized as per your institution’s policies. After a full endosonographic evaluation, the FNA needle is introduced into the center of the cyst, carefully aspirating nearly the entire cyst contents. It is our practice to use a 22‐gauge FNA needle for most cysts measuring 2–3 cm in diameter, and a 19‐gauge needle for cysts over 3 cm or previously known to have a highly viscous fluid. If alcohol lavage is used, the near‐complete cyst aspiration will be followed by alternately filling and aspirating the cyst with alcohol for three to five minutes, using an amount equal to the mucinous fluid originally aspirated. A rim of fluid should be kept around the needle tip at all times to avoid damaging the cyst wall and possibly injecting alcohol into the surrounding parenchyma. After the lavage agent is aspirated out (leaving a small amount of alcohol around the needle tip), the chemoablation agent is infused, replacing no more agent than is required to refill the cyst to its original volume and dimensions [11]. Based on the results of the randomized prospective CHARM trial, it is our practice to use a completely alcohol‐free approach, which is simpler, faster, and safer than ablations that include alcohol lavage. In this approach, the lavage step of the procedure is eliminated and instead, after initial cyst aspiration, a mixture of gemcitabine (38 mg/mL) and paclitaxel (6 mg/mL) is infused into the cyst, using an amount equal to the volume of mucin originally aspirated and refilling the cyst to its original dimensions (Figure 34.1). Paclitaxel is highly viscous, and the infusion of the chemotherapy agent in a timely fashion through a 22‐ or 19‐gauge FNA needle requires moderately high pressure, so an infusion apparatus such as a syringe strapped to a high‐pressure gun or infusion device is often used [21] (Figure 34.2). Antibiotics are recommended as per ASGE guidelines on pancreatic cyst management, and it has been our approach to observe these patients for one hour postoperatively. DiMaio et al. [28] demonstrated that serial cyst ablations (similar to the concepts for treating dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus) are more effective than a single ablation session for pancreatic cystic tumors. Therefore, it is the approach at our institutions to schedule two to three alcohol‐free gemcitabine–paclitaxel chemoablation infusions at three‐month intervals where residual cyst at the second and third endoscopies measuring over 15 mm in diameter are retreated. This is followed by clinic evaluation and follow‐up cross‐sectional imaging 12 months after the last ablation with either enhanced MRI (preferred) or CT scan to measure treatment response and assess for complications (Figures 34.3 and 34.4). The definition of treatment response has been standardized over multiple studies and is based on cyst volume (4/3πr3, where r is cyst radius) and is defined as complete (≥95% reduction of cyst volume), partial (94–75% reduction), or non‐response (<75% reduction) at one‐year follow‐up [15–21]. It is our practice that patients then return for follow‐up imaging one year later and subsequently re‐enter a surveillance program using the post‐treatment measurements and cyst characteristics to govern surveillance frequency [1,2]. Figure 34.1 The alcohol free EUS‐guided cyst ablation process. The FNA needle is introduced into the center of the cystic lesion (a). This is followed by near‐complete aspiration of the mucinous fluid from all compartments, leaving a small amount of fluid around the needle tip to assure that the walls of the cyst are not injured (b). The cyst is then immediately refilled with the chemoablation agent, infusing the same volume as was originally aspirated, refilling the cyst to its original dimensions and volume (c). This alcohol‐free approach is simpler, faster, and safer than protocols which use alcohol lavage as part of the ablation process. Figure 34.2 A high‐pressure gun, syringe, and short connector tubing assembly which can be used to quickly infuse viscous ablation agents into a cyst after the mucinous fluid is aspirated. It is important to acknowledge that even if a treated cyst achieves the definition of complete ablation, the patient’s risk of developing pancreatic adenocarcinoma has likely been significantly reduced but not completely eliminated. Histologic assessment of residual cyst epithelium is not possible without surgical resection and there are no high‐quality studies to date proving that cyst ablation prolongs life expectancy. Two large retrospective multicenter Japanese studies demonstrate that in patients under long‐term surveillance for IPMN (some of which had been treated surgically), there remains a 2–4% risk of developing a metachronous pancreatic malignancy in the remaining pancreas [29,30]. Additionally, recent evidence shows an ongoing and progressive risk of malignant transformation of IPMNs during long‐term surveillance [26]. Consequently, even patients who achieve a complete ablation should remain in surveillance as long as further therapy would be appropriate; furthermore, whether a surgical, ablative or surveillance strategy is employed, the current understanding is that long‐term surveillance will be required until patient age and/or comorbidities make further surveillance unwarranted. Figure 34.3 (a) Magnetic resonance image showing a 76‐year‐old female with a 4.2‐cm mucinous‐type (premalignant) pancreatic cyst (white arrow) before EUS‐guided chemoablation. (b) CT image showing a 4‐mm residual defect at one year (black arrow). Figure 34.4 (a) MRI (top) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (bottom) of an 83‐year‐old male with a 2.7‐cm intraductal mucinous pancreatic neoplasm prior to EUS‐guided chemoablation. (b) Follow‐up MRI (top) and MRCP (bottom) reveals no evidence of residual cyst at six‐month follow‐up evaluation. EUS‐guided pancreatic cyst ablation is a promising, rapidly evolving, and minimally invasive technique for the treatment of premalignant pancreatic cystic neoplasms, which currently have therapeutic options limited to either indefinite surveillance or major pancreatic surgery. Careful patient selection is paramount, as is careful attention to the technical aspects of the procedure, postprocedure care, clinical follow‐up, and quality assurance. Recent clinical evidence indicates the durable treatment response of cyst ablation when a complete response is achieved and a significantly improved safety profile with an alcohol‐free ablation protocol. This emerging technique significantly expands treatment options for appropriately selected patients; however, as is typical in most novel and innovative procedures, areas of uncertainty and controversy exist. Additional studies are needed to further develop the technique and to determine which patients are most appropriately offered this emerging treatment option based on efficacy, safety, patient satisfaction, and cost.

34

How to do EUS‐guided Pancreatic Cyst Chemoablation

Background

Pretreatment evaluation

Patient selection

Author, year

Study type

Protocol (no. of patients)

Complete (CR) or partial resolution (PR)

Clinically significant adverse eventsa

EtOH lavage only

Gan et al. (2005) [14]

Prospective (pilot)

5–80% EtOH (25)

35% CR

7% PR

0%

Dewitt et al. (2009) [15]

Prospective (RCT)

80% EtOH (25)

Saline (17)

33% CR

0% CR

24% (4% pancreatitis, 20% abdominal pain)

12% (abdominal pain)

Gomez et al. (2016) [16]

Prospective (pilot)

80% EtOH (23)

9% CR

44% PR

8% (4% pancreatitis, 4% abdominal pain)

EtOH lavage + paclitaxel infusion

Oh et al. (2008) [17]

Prospective

88–99% EtOH + paclitaxel (14)

79% CR

14% PR

21% (7% pancreatitis, 14% abdominal pain)

Oh et al. (2009) [18]

Prospective

99% EtOH + paclitaxel (10)

60% CR

20% PR

10% (abdominal pain)

Oh et al. (2011) [19]

Prospective

99% EtOH + paclitaxel (47)

62% CR

13% PR

4% (2% pancreatitis, 2% abdominal pain)

DeWitt et al. (2014) [20]

Prospective

100% EtOH + paclitaxel (22)

50% CR

25% PR

23% (10% pancreatitis, 13% abdominal pain)

EtOH lavage + paclitaxel/gemcitabine infusion vs. saline lavage + paclitaxel/gemcitabine infusion

Moyer et al. (2017) [21]

Prospective (RCT)

80% EtOH + paclitaxel/gemcitabine (18)

Saline + paclitaxel/gemcitabine (21)

61% CR

67% CR

28% (6% pancreatitis, 22% abdominal pain)

0%b

Indications

Contraindications

Relative contraindications

Technical aspects of the procedure

Postoperative care and follow‐up

Conclusions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree