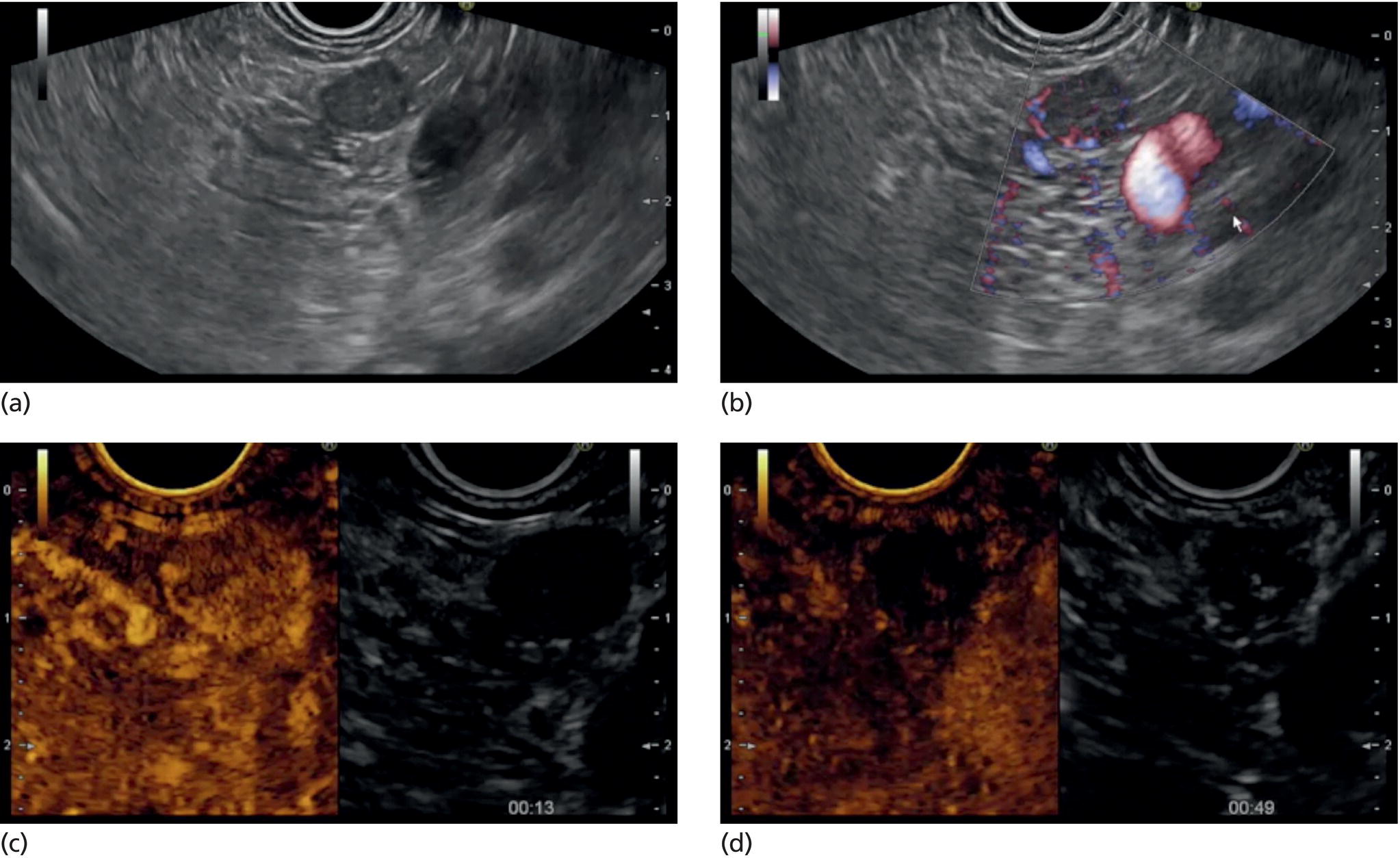

Marc Barthet, Mohamed Gasmi, and Jean‐Michel Gonzalez Digestive endoscopy and gastroenterology department, North Hospital, Marseille, France EUS‐guided radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has recently emerged as a new technique for pancreatic tumor ablation, mostly neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), pancreatic cystic neoplasm (PCN), or pancreatic adenocarcinoma. NETs are probably an indication of choice for EUS‐guided RFA. NETs are mostly non‐functional and do not induce secretory disorder [1]. Once their nature is yielded by diagnostic tests such as EUS‐guided fine needle aspiration (FNA), incidental nonfunctional NETs currently lead to management difficulties when their largest diameter is less than 2 cm [2–4]. In patients with tumors ranging in size from 1 to 2 cm, therapeutic surgical choices could be challenged by EUS‐guided treatment [5–7]. An interesting alternative to surgery could be destruction with endoscopic RFA [8–11]. About five series have been published including NETs or PCNs, most of them being retrospective or including only few patients [12–16]. In addition, the follow‐up of the patients in these series is short, less than 13 months [12–16]. The short‐term efficacy in these series ranges between 71.4 and 100% for NETs, but the long‐term outcome and risk of recurrence are still unknown [12–16]. Despite these interesting results regarding short‐term efficacy, surgery remains the treatment of choice in the absence of long‐term follow‐up and randomized series. However, with regard to the results of surgical resection of benign tumors, the mortality rate is 3–14% and morbidity rate 15–30%, compared to no mortality and morbidity of 3–10% [17,18]. Studies assessing the results of EUS‐guided RFA were conducted between 2015 and 2019 [12–16]. Of these, three were prospective studies with a follow‐up ranging from six months to one year [12,14,15]. Our team conducted a multicenter prospective study between February 2015 and February 2017 with a one‐year follow‐up [14]; recently, the long‐term outcome of these patients with follow‐up at three to five years became available. Endoscopic examination should be performed with an EUS therapeutic scope. In the case of NETs, the operative needle can be used directly. EUS‐RFA can be performed with a 19G RFA needle (Starmed, Taewong, Korea) applying a 50‐W current under continuance mode setting until reaching 100 Ω impedance (appearance of white bubbles) and not exceeding 500 Ω. RFA was stopped either when the ultrasound operator saw white bubbles alongside the needle and outside the targeted lesions or when the impedance exceeded 100 Ω. RFA duration was usually 15–45 seconds. One to three shots can be performed during the same session: one shot for pancreatic NETs (pNETs) of 1 cm; three shots for pNETs of 15–20 mm. Normally, operators should not exceed three shots because of the risk of further complications such as pancreatitis or ductal damage (biliary or pancreatic), mainly if the lesion is located in the head of the pancreas. Another device is also available: a thin radiofrequency probe that can be introduced into the lumen of a 19G FNA needle and ejected from the needle tip for application of radiofrequency abaltion (Habib™ EndoHPB probe, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA). With this device, white bubbles due to thermic injury are often difficult to see. The use of contrast‐enhanced harmonic (CEH)‐EUS is recommended before and after applying EUS‐guided RFA (Figure 44.1). A recent series in 19 patients with solid abdominal tumors demonstrated the usefulness of targeting EUS‐guided RFA using CEH‐EUS findings [19]. As pNETs are usually hypervascularized, CEH‐EUS allows targeting of the RFA application. Particularly in large pNETs close to 2 cm in size, areas of sustained hypervascularization could persist despite multiple shots, which should not exceed three attempts (unpublished data). In such cases, postoperative CEH‐EUS may allow any remaining vascularized areas to be targeted for a subsequent shot. Figure 44.1 EUS‐guided RFA with contrast enhancement control for NET located in the body of the pancreas. (a) EUS view of NET located in the body of the pancreas, 11 mm size, homogeneous. (b) EUS view of NET with fine Doppler showing peripheral arterial vascularization. (c) CEH‐EUS view of NET showing early hyperenhancement. (d) Immediate CEH‐EUS view of NET after EUS‐RFA showing no more enhancement of the treated NET. Prophylaxis should be instituted to prevent acute pancreatitis, infection, and perforation [14]. Rectal diclofenac was used, as recommended before endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), to prevent post‐endoscopic pancreatitis. Antibiotic prophylaxis (2 g of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid intravenously) was used to prevent infection. Suctioning the main fluid content in cases of pancreatic cystic neoplasm was performed before RFA in order to avoid excessive transmission of radiofrequency current into the liquid component. Starting with EUS‐guided RFA for pNETs, only patients unfit for surgery were selected for EUS‐guided RFA [5,7,8–16]. International recommendations (European NET guidelines and the revised NCCN guidelines) suggest follow‐up for pNETs under 1 cm and surgery for pNETs over 2 cm because of the high risk of lymph node and distant metastasis [20–22]. However the management of pNETs ranging between 1 and 2 cm in size is debated. The balance between the spontaneous risk of lymphatic or metastatic spreading (up to 28%) and the morbidity and mortality of surgery (10–30%) should be considered [17,18,20–22]. As the morbidity of EUS‐guided RFA is low (3–10%), it is increasingly accepted that it should be indicated for lesions ranging between 1 and 2 cm in size [5–7,11–16]. If the indications for EUS‐guided RFA should be restricted to pNET diameters of 1–2 cm, the pathology should be assessed before any EUS‐guided management. Only pNETs belonging to grade 1 of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification should be treated with EUS management, since grade 2 or 3 pNETs lead to excessive risk for lymph node or metastatic spreading. The accuracy of FNA for grading using the WHO classification seems to be accurate in more than 75% of cases [23]. Therefore only patients with grade 1 pNETs of 1–2 cm should be considered for EUS‐guided RFA. An increasing number of studies have evaluated EUS‐guided RFA for treating premalignant pancreatic tumors (i.e. NETs), but most of them either include a small number of patients or are retrospective [12–16]. Five series studying EUS‐guided RFA of NETs have been published [16–20], three of them being prospective and including one to twelve patients [12–16,24,25]. Even though the efficacy for NETs is 71.4–100% and for PCNs 48.4–65%, the long‐term results are still unknown and we cannot rule out the risk of recurrences or an unfavorable outcome such as early malignancy [18,24–26]. With regard to efficacy, promising initial results using the dedicated cooling needle or Habib probe in the treatment of pNETs have been shown in short series (3 to 30 patients of a total of 51 patients) [12–16]. Interestingly, in one series comprising three functional NETs (insulinomas), rapid symptomatic and biological improvement occurred within two days following the procedure, with sustained results at two years follow‐up [13]. With regard to the efficacy of treatment for pNETs, one series found complete resolution in 70–85% at one year follow‐up despite an incomplete significant response in 70% at six months follow‐up [14,16]. Some delayed response could occur after six months follow‐up, probably due to stimulation of immune responses [14]. The overall morbidity rate in the largest prospective series was three cases (10%) [14]. In two of the cases, the morbidity was due to acute pancreatitis with early infection in one, and perforation of adjacent jejunum in the other. After modifying the study protocol to reduce the risk of pancreatitis, infection or damage to adjacent organs in cystic lesions, only one case occurred (3.5%). This was an obstructive pancreatitis due to fistulization of an NET within the main pancreatic duct; the case was successfully treated by ERCP, including pancreatic sphincterotomy and stenting. One year later, all these three patients were doing well with no tumor present. Very few data about the safety of the technique can be found in the articles about EUS‐guided RFA in PCN [12–16]. Pai et al. [12] applied EUS‐guided RFA using the Habib probe in six PCNs (four mucinous cystadenomas, one intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm [IPMN], and one cystic NET) and two patients experienced transient mild pain that resolved within three days [12]. In all the published series, the longest follow‐up was 13 months [12–16]. Long‐term data from the largest prospective series including 30 patients have been presented recently [14, and unpublished data]. A total of 12 patients had 14 pNETs, the series comprising seven males (58%) and five females, with a mean age of 59.9 years (range 45–77 years). All NETs were well differenciated and non‐functional and belonged to OMS grade 1 classification, associated in one case with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1. The mean size of the NETs was 13.1 mm (range 10–20 mm), with three located in the head, six in the body, and five in the tail of the pancreas. Patients were followed for at least three years (mean 45.6 months), the last patient being included in February 2017; mean age at the end of follow‐up was 62.5 years (range 52–87 years). The mean duration of follow‐up was 42.9 months (range 36–53 months). Two males (aged 52–77 years) died during follow‐up at 42 months from causes other than the inclusion criteria: one patient who had MEN‐1 and NET committed suicide; the other, originally treated with EUS‐guided RFA for an IPMN located in the head of the pancreas and who had no cystic lesions in the tail of the pancreas, developed cancer in the tail of the pancreas. At one‐year follow‐up, 12 NETs (85.7%) had completely disappeared or exhibited necrosis. Two were considered failures. At the end of follow‐up (45.6 months), 12 NETs had completely disappeared. One of the patients exhibited a small hyperechoic scar at six months’ follow‐up, with no contrast enhancement on computed tomography (CT) and EUS and negative FNA. The scar remained stable from 6 to 41 months of follow‐up. Another patient, initially considered a failure at one year because the cystic lesion located in the tail of the pancreas still measured 20 mm, exhibited no contrast enhancement on EUS. At the end of follow‐up (53 months), the lesion disappeared completely on CT scan and EUS. There were two failures, of whom one was a recurrence after disappearance at one year and another had persistent disease at one‐year follow‐up. With regard to the RFA indications for NETs, the long‐term results of EUS‐guided RFA in the 14 lesions in 12 patients appeared to be stable, with 85.7% success at one year and at the end of follow‐up. In fact, despite these stable results, there was one late response and one late recurrence. In one case considered a failure at one year, the tumor disappeared completely at 53 months follow‐up. It was a 20‐mm lesion located in the tail of the pancreas that completely disappeared at one year on CEH‐EUS. This delayed success may be related to activated immune responses related to RFA [14]. Conversely, an 18‐mm NET located in the body of the pancreas seemed to disappear at one year after its size decreased to 13 mm at six months but it reoccurred at 42 months’ follow‐up, measuring 16 mm. No enhancement on CEH‐EUS could be demonstrated but EUS‐FNA showed well‐differentiated endocrine cells belonging to a G1 WHO classification. We have no clear explanation for this late and benign recurrence. Although the protocol of this study specified only one RFA shot of 50 W not exceeding 100 Ω, we now apply one to three shots depending on the results of immediate CEH‐EUS. After considering the complete diffusion of the white bubbles into the volume of the tumor, we controlled by CEH‐EUS. In cases of persistent contrast enhancement, we added a targeted RFA shot. The same approach has been promoted by other authors [22,24,25]. A recent series of 19 patients with solid abdominal tumor demonstrated the usefulness of targeting EUS‐guided RFA with CEH‐EUS findings [22]. Unfortunately, one case showed an unfavorable outcome, with metastatic spreading in a 65‐year‐old female. The lesion was located in the body of the pancreas. measuring 19 mm at inclusion with a G1 WHO classification at FNA. She was considered a failure at one year, with a 12‐mm lesion at six months and a 16‐mm lesion at one year. She received a second session of EUS‐RFA at 23 months, the size of the lesion decreasing to 13 mm. She developed asymptomatic liver metastases at 36 months, with PET scan identifying an intense uptake on liver metastases and pancreatic tail. The patient is doing well and receives somatostatin therapy. As we did not understand the metastatic outcome, we requested a pathological re‐examination of the first FNA, and this corrected the WHO classification from G1 to G2. It has been shown in the literature that the accuracy of FNA for an adequate WHO classification is not complete, ranging from 74 to 87.5% [23]. This could explain the discrepancy between the two pathological results, emphasizing that long‐term follow‐up is always required, and in case of failure at one year surgery should be recommended, despite one delayed healing case occurring after one year follow‐up. In this series, in the event of RFA failure the risk of unfavorable and metastatic outcome is 50%. Nevertheless, in our case, the patient was not operable, leading to a second RFA session at two years’ follow‐up and discovery of metastatic liver spreading at 36 months. The risk of developing further malignancy during the follow‐up of NETs larger than 2 cm has been estimated to be up to 27.3% for lymph nodes and 9% for metastases [27]. The European NET guidelines and the revised NCCN guidelines suggest surveillance for lesions under 2 cm (and no more surgery) [20–22]. Pancreatic surgery for NETs is associated with a mortality rate of 3–6% and morbidity rate of 14–58%, mainly due to pancreatic fistula [17]. In the same systematic review, the five‐year overall survival and disease‐specific survival were, respectively, 85% and 93%. A randomized series comparing surgical resection and EUS‐guided RFA should be conducted. EUS‐RFA management of pNETs is associated with an efficient long‐term outcome, with size ranging between 1 and 2 cm and grade 1 WHO classification. Complete disappearance of NETs occurs in 85.7% of cases, with morbidity lower than 10%. Marc Barthet received a research grant from Boston Scientific (endoscopic gastrojejunal anastomosis).

44

How to do EUS‐guided Radiofrequency Ablation of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors

Introduction

Methods for EUS‐guided RFA

Technique

Prophylaxis for complications

Indications

Results for EUS‐guided RFA studies

Overall results

Results of long‐term follow‐up

Conclusion

Conflicts of interest disclosure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree