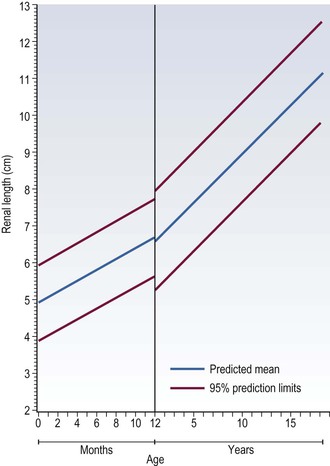

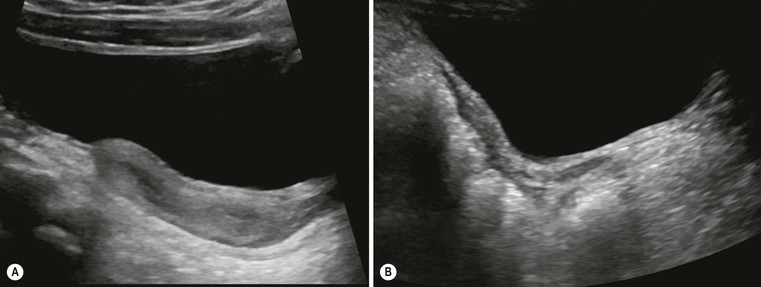

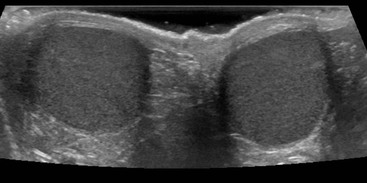

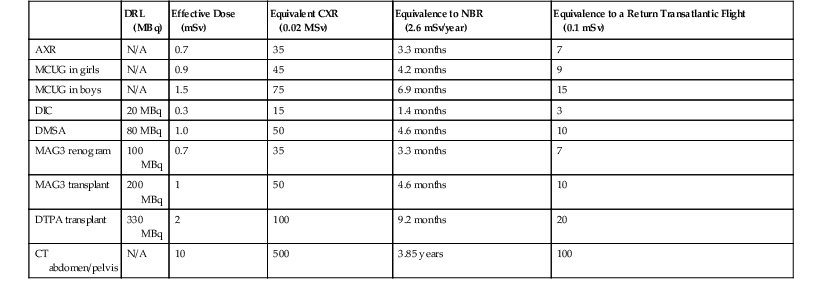

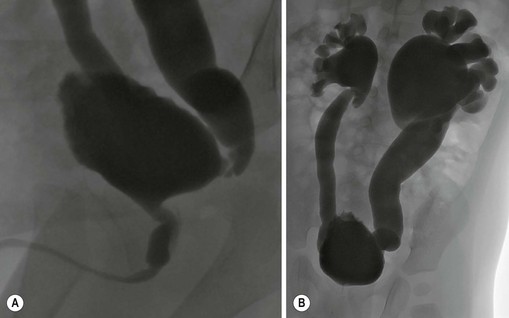

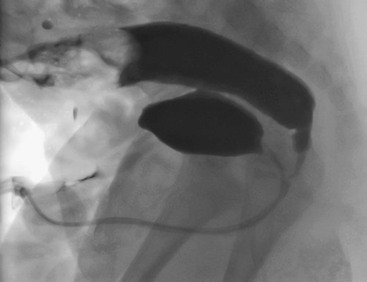

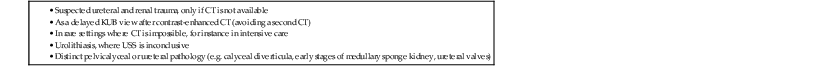

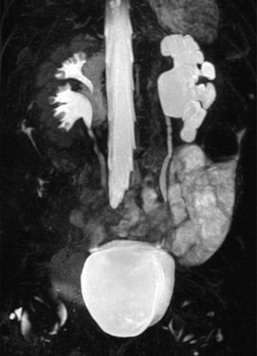

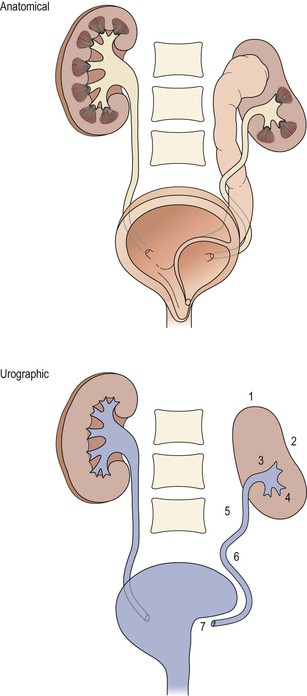

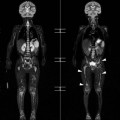

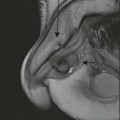

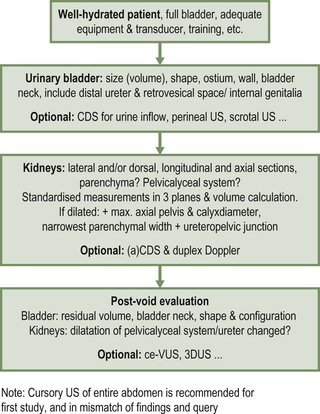

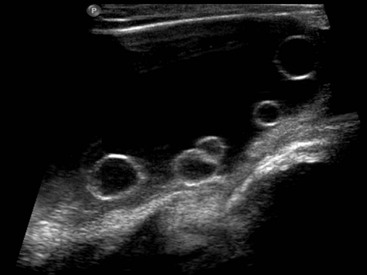

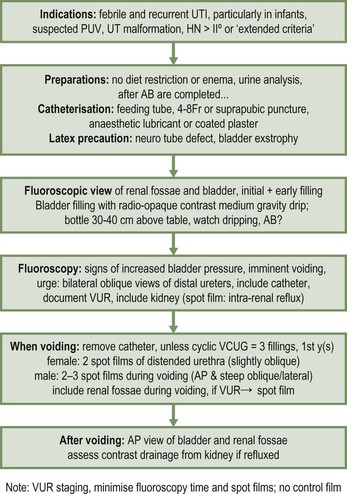

Owen Arthurs, Marina Easty, Michael Riccabona In this chapter, we cover the important areas of renal, urinary tract and pelvic imaging in children, emphasising the importance of congenital abnormalities and the need for minimising radiation burden and optimising image quality. Ultrasound (US) is the preferred method for imaging the paediatric population, due to the ease of availability, lack of ionising radiation, reproducibility and because it is usually well tolerated. Modern US is often the only modality required to make a diagnosis, with the high frequency probes and new technology producing exquisite anatomical details in children who are ideal subjects. Alternatively, US can be used to direct other imaging modalities, such as functional assessment of the urinary tract by 99mTc-MAG3 dynamic imaging. Intravenous urography (IVU) is now rarely used. Fluoroscopic micturating cystourethrography (MCUG) is essential to exclude bladder outflow obstruction such as in posterior urethral valves and urethral pathology, and to assess for vesicoureteric reflux (VUR). Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ce-VUS) with micro-bubble contrast is used in some European countries rather than a fluoroscopic examination for VUR assessment, avoiding the radiation burden from conventional MCUG. Direct isotope cystography using 99mTc-pertechnetate is a low-dose functional study used to assess VUR, particularly in girls, where urethral anatomy is usually normal. Older, continent and cooperative children may benefit from an indirect radionuclide cystogram, IRC, as part of their dynamic 99mTc-MAG3 renogram, as a non-invasive means of assessing for VUR. Cross-sectional imaging—computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—is crucial in tumour imaging, for disease staging and prognostication as well as for imaging complications. CT is used much less frequently in children than in adults for urolithiasis: indeed, only severe trauma imaging relies on CT in children. The role of MRI is increasing both for anatomical and functional diagnostic information, particularly in cooperative older children, and where nuclear medicine is not available. Conventional angiography is reserved for specific clinical indications, and is invasive with a high radiation burden. CT and MR angiography (MRA), however, have emerged as replacements for angiography for many diagnostic purposes. Here we review the relative strengths and weaknesses of these techniques, illustrated using specific pathologies and recommend imaging algorithms. Radiographs still have a role to play in babies with congenital renal anomalies, particularly in those cases associated with skeletal anomalies, such as vertebral segmentation anomalies and pubic diastasis (in bladder exstrophy). They may show renal tract calculi (Fig. 78-1) where the exposure should be coned to the kidneys, ureters and bladder (so-called ‘KUB film’). Age-appropriate exposure settings and electronic filtering (in digital radiography equipment) are essential. Ultrasound is the most useful way of providing anatomical information about the intra-abdominal, pelvic and retroperitoneal structures. The ability to delineate and recognise normal and abnormal findings is directly related to the skill of the ultrasonographer and the equipment used, including high-frequency transducers, and familiarity examining children in a conducive environment, with knowledge of the spectrum of diseases in childhood being paramount. Several European guidelines regarding standard paediatric urinary tract US are available.1 In the young child, ideally a full bladder is necessary, which usually requires at least 30–60 min of encouraged fluid intake to allow adequate hydration. Any US examination of the abdomen should begin by imaging the bladder, to fortuitously attempt to capture a full bladder (as the infant in nappies may void at any time). The distended bladder provides an acoustic window for the lower urinary tract, bladder neck and ureteric orifices (vesicoureteric junction), distal ureters, internal genitalia, retrovesical space, pelvic musculature and vessels (Fig. 78-2).1 It is customary to measure pre- and post-micturition bladder volumes, as incomplete voiding may be related to bladder dysfunctions and urinary tract infections, and the presence of pre- and/or post-micturition upper tract dilatation. Normal age-related changes in the kidney must be appreciated. The neonatal kidneys lack renal sinus fat over the first 6 months of life, and the medullary pyramids are typically large and hypoechoic relative to the cortex (the opposite to that found in older children and adults), which may be mistaken for pelvicalyceal dilatation or ‘cysts’ (Fig. 78-3). The normal neonatal renal cortex is also hyper- to iso-echoic relative to the adjacent normal liver, which again can often be reversed in adults. The neonatal renal pyramids may be echogenic, a transient physiological appearance in up to 5% of newborns, and should not be mistaken for nephrocalcinosis, although it can be seen in older infants with dehydration.2 The average newborn kidney is approximately 4.5 cm in length, and measurements of bipolar renal lengths can be compared against age/height/weight indexed charts (Fig. 78-4). As the paediatric kidney is more spherical than the ellipsoid adult kidney, renal volumes may be a better assessment using the equation: Colour Doppler sonography (CDS) of the renal vessels is particularly important in assessing perfusion in a variety of conditions, including infection (segmental perfusion impairment), trauma (hilar vascular injury), biopsy (post-biopsy complications), renal failure, urolithiasis tumours, renal transplants and hypertension, and for the vascular anatomy in hydronephrosis (HN). High-frequency linear transducers yield better images in smaller children, especially in the prone position and should be performed for detailed analysis in all examinations.1 Normal pelvic structures can be difficult to visualise in children: visualisation of the ovaries by US depends on their location, size and the age of the girl—they are more easily seen in the first few months of life. Ovarian volume is usually under 1 mL in the neonate, and 2–4 mL in the prepubertal child. Ovaries typically look heterogeneous due to the presence of follicles, and larger follicles can appear as small ovarian ‘cysts’ which are normal at all ages (Fig. 78-5). After puberty, ovarian volumes of 5–15 mL are normal, with normal primordial follicles <10 mm in diameter, and stimulated follicles 10–30 mm in diameter. The normal uterus also changes dramatically with hormonal changes, and is the most useful guide to pubertal staging. The neonatal uterus is prominent due to circulating maternal oestrogens, typically measuring 2–4.5 cm in length, with thickened and clearly visible endometrial lining (Fig. 78-6A). By 1 year of age it becomes smaller, has changed to the prepubertal tubular appearances: the fundus and cervix are the same size and the endometrium is no longer visible (Fig. 78-6B). At puberty, the fundus starts to enlarge, becomes up to three times the size of the cervix, with a total uterine length of 5–7 cm and the typical adult pear-like shape. The endometrial appearances will clearly vary with the phase of the menstrual cycle. The vagina may be visualised by US if airfilled, (shown as a linear bright echo), or if fluid filled. On MRI the vagina is best seen on sagittal T2-weighted spin-echo MRI. As with the uterus, the appearance and the thickness of the vaginal epithelium and the signal from the vaginal wall change with the age and the phases of the menstrual cycle. Ultrasound genitography with saline filling of the vagina, or 3D US can be used for uterine anomalies, and perineal US for vagina and urethral pathology.3,4 The prostate has an ellipsoid homogeneous appearance, but is difficult to see in newborns, as are the seminal vesicles. As the processus vaginalis remains open for some time after birth (and may never close completely), hydroceles are considered a normal physiological finding in the newborn. Cryptorchidism is discussed later in this chapter. The normal testis changes in appearance during childhood. It has a homogeneous hypoechoic echotexture and is spherical/oval in shape during the neonatal period, measuring <10 mm in diameter (Fig. 78-7). The epididymis and mediastinum testis are usually not seen at this point, but are clearly identified by puberty. Testicular size in adolescence ranges from 3 to 5 cm in length and from 2 to 3 cm in depth and width (2–4 mL in total). Testicular flow, as measured by Doppler US, also changes with age. The testis in infants shows very low-velocity colour flow, which can be difficult to see despite optimised slow-flow settings, and even normal prepubertal testes may show not exhibit low-velocity flow on power Doppler US. Technically it may be difficult to identify abnormalities in a single testis given the wide range of normal values, and thus a side-by-side comparison can be most useful. There are several ways to visualise the bladder in the paediatric population. The method of choice depends both on the type of pathology suspected and the age of child. All methods, apart from the 99mTc-MAG3 IRC, require a bladder catheter, which becomes more unpleasant for both child (and the carer who observes) as the child gets older. The modern MCUG, using pulsed fluoroscopy, digital image amplifiers and last image hold, means that high-quality imaging is now available at an acceptably low radiation dose (Table 78-1). The direct isotope cystogram is useful in the assessment of VUR in young babies (before toilet training), particularly in girls where there is no need to demonstrate the urethral anatomy, or for screening other family members when the index of suspicion for reflux is high. If the male baby is found (on US) to have significant bilateral hydronephrosis (HN), a dilated ureter, a pathological urethra or a thick-walled bladder, an MCUG is then performed.5 MCUG is also indicated for VUR assessment, such as after (recurrent or complicated) UTI, or for assessing complex malformations that involve the urinary tract. The MCUG is the only accepted method of lower urinary tract imaging to demonstrate the urethral anatomy clearly, although perineal US performed during voiding also allows assessment of the urethra. It is essential in boys, where urethral pathology is suspected: for example, in boys with suspected posterior urethral valves (Figs. 78-8 and 78-9), cloacal anomaly, or anorectal anomaly and suspected colovesical fistula (Fig. 78-10). The fistula may not be seen on an MCUG. A distal loopogram (i.e. intubating the distal limb of the colostomy and injecting radio-opaque water-soluble iodine-containing contrast under pressure is the best technique to delineate these connections. A sterile narrow feeding tube is used to catheterise the neonatal urethra, secured with tape. A suprapubic catheter may be used in individual cases, or in-dwelling Foley catheter, provided that the balloon is carefully deflated in order to prevent bladder pathology being obscured, or obstruction to bladder emptying increasing the chance of bladder rupture.1 Warmed water-soluble iodinated contrast is then dripped from a height of no greater than 60 cm (physiological filling pressure of 30–40 cm water). Rapid bladder filling using a syringe may generate high pressures leading to bladder overextension and artificial VUR, as well as altered bladder capacity values. Bladder capacity increases during the first 8 years of life and normal bladder capacity for children 0–8 years can be estimated using the equation (age + 1) × 30 mL. Early bladder filling views are obtained with the child supine. Tight coning is important to reduce dose. Oblique views are then obtained to assess the vesicoureteric junction and urethra on voiding. In the first few years of life, cyclical filling is advocated, as there is an increased chance of detecting VUR with consecutive voiding cycles.1 The bladder is refilled and on the second or third void, the catheter is removed so that a well-distended urethral view is obtained. Prophylactic oral or intravesical antibiotics are used, and MCUG is contraindicated in the presence of a urinary tract infection. In a modified MCUG, the contrast infusion is monitored for stopping or backflow in drip rate, which may represent dysfunctional sphincter or detrusor contractions, indicating functional disturbances.6,7 Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography (ce-VUS) is a non-ionising alternative used throughout Europe, but less commonly used in the UK. Recommended indications for ce-VUS presently include screening populations, in girls, bedside investigations and for follow-up, although none of the ce-VUS contrast agents are currently licensed in children. Study recommendations and VUR grading are available (Fig. 78-11).1,8 Typically, SonoVue (Bracco/Italy) at 0.2–1.0% of bladder filling volume is given via urinary catheter as for MCUG by saline drip, following standard renal tract US views. Dedicated low-MI contrast imaging of both kidneys and the bladder including the retrovesical space and the urethra during and after filling is performed, with echogenic microbubbles in the ureters or renal pelvis indicating VUR. A DIC is predominantly used to detect the presence of VUR in baby girls, or as VUR follow-up in baby boys. Catheterisation using a 6Fr feeding tube can usually be performed with the baby lying on the Gamma camera, wearing a double nappy. Twenty megabequerels of 99mTc-pertechnetate is introduced into the bladder followed by warmed saline. The baby is restrained with sandbags and Velcro straps, and bladder filling is performed twice. The baby will spontaneously void when the bladder is full and VUR evaluated. The kidneys are kept in the field of view at all times to detect VUR. This is a useful, well-tolerated and physiological procedure to assess bladder function and for the presence of VUR. It is performed at the end of dynamic renography in cooperative and toilet-trained children who can void on demand. After a non-diuretic stressed dynamic 99mTc-MAG3 renogram, the gamma camera is turned vertically Children seated on a commode with their backs to the camera. Boys may stand and void. The acquisition is started just before voiding starts and continues for 30 s after voiding, up to approximately 2 min total acquisition time, if required. The study can be repeated if there is still tracer present in the bladder when bladder emptying is incomplete, or when refluxed tracer re-enters the bladder from the upper renal tract. Bladder dysfunction can be assessed and VUR can be seen on the dynamic study. Guidelines are available from the European Association of Nuclear Medicine.9 Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) is used as a 99mTc tracer; it is filtered by the glomeruli and reabsorbed, binding to the proximal convoluted tubules to give a static image over several hours. Approximately 10% of the tracer is excreted in the urine. Routinely, three posteriorly acquired views are obtained (posterior, right and left posterior oblique views), with anterior views used in abnormal renal anatomy (transplants, pelvic and ectopic kidneys) or scoliosis. Anterior and posterior views may then be used to estimate the differential renal function (DRF) by the geometric mean. As renal DMSA uptake relies on sufficient glomerular clearance, sufficient renal function is essential for meaningful results, as well as sufficient urinary drainage from the renal pelvis to avoid tracer pooling artefacts. The main use of the 99mTc-DMSA scan is in the assessment of the DRF and cortical abnormalities, such as renal scarring, fusion defects, ectopic or duplex kidneys and in hypertension (e.g. Fig. 78-12). DRF may also be helpful for pre- and post-transplant assessment and in abdominal tumours, where the renal blood supply may be at risk, or where the kidney lies in the radiotherapy field. All indications are given in Table 78-2. There are no contraindications. TABLE 78-2 Indications for 99mTc-DMSA Examination Dynamic renography is used to assess split renal function and drainage from the renal collecting systems in suspected obstruction.10 In Europe, the most common isotope used in paediatric dynamic imaging is 99mTc-MAG3, which reflects tubular function. 99mTc-DTPA is also utilised, and uptake reflects glomerular function; thus, it is more commonly is used to calculate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and is the least expensive renal imaging agent capable of dynamic assessment. After intravenous administration, about 50% of the 99mTc-MAG3 in the blood is extracted by the proximal tubules with each pass through the kidneys. The 99mTc-MAG3 is then secreted into the lumen of the tubule. As 99mTc-DTPA is filtered by the glomerulus, with only 20% extraction fraction, it is not a good agent to use in neonates, children with impaired renal function or in the presence of significant obstruction. In 99mTc-MAG3 studies, if there is dilatation of a collecting system, a diuretic is used such as furosemide at a dose of 1 mg/kg (maximum dose 20 mg). Timing of diuretic administration varies widely, but may be given just after the tracer to try to prevent loss of venous access later in the study, in a distressed child. Time activity curves are generated which demonstrate uptake and excretion. Analogue images in the uptake phase may demonstrate renal scarring, albeit less clearly than on the 99mTc-DMSA static renal scan. Split renal function can also be calculated—being even more accurate than static renography in a significantly obstructed kidney. The indications are given in Table 78-3. Where VUR is suspected, and the child is toilet-trained, cooperative and continent, an IRC may be performed. The children are encouraged to drink plenty so that they are well hydrated upon arrival at the department (which is essential for meaningful results). The administered dose is scaled on a body surface area basis, with a maximum dose of 100 MBq of 99mTc-MAG3. The child empties the bladder, lies supine on the camera face, distracted by television or a film, and is immobilised with sandbags. Ten- to 20-s frames are acquired for 20 min following isotope injection, imaging the heart, kidneys and bladder. The child then voids again before returning to the gamma camera for images following postural change and micturition, at about 40 min post injection. The DRF estimation is calculated from the renogram between 60 and 120 s from the peak of the vascular curve, expressed as a percentage of the sum total. The recommended methods to evaluate the DRF are the Patlak–Rutland plot and the integral method. Interpretation of the renogram in a dilated kidney, such as pelviureteric junction obstruction (PUJO) needs to be performed carefully. The shape of the time activity curve, response to furosemide and drainage of the collecting system following a change of posture and micturition are evaluated for significant stasis of tracer. There are four classic drainage patterns, described as normal (I), obstructed (II), dilated unobstructed (IIIa) and equivocal (IIIb). Ideally the renogram should be assessed with the US images available so that the degree of HN and the renal parenchyma can be evaluated. Normal kidneys with DRF below 45% should be monitored using US. If dilatation increases, and a 99mTc-MAG3 demonstrates stepwise fall in function, pyeloplasty may prevent further deterioration in renal function. With advances of sophisticated US techniques, and availability of cross-sectional imaging, and widespread use of renal scintigraphy, the use of intravenous urography (IVU) has decreased with very few indications remaining (Table 78-4).11 Except for urolithiasis, an initial ‘control’ full radiograph is rarely indicated. The radiation exposure should be minimised, using 1–3 properly timed and coned views (KUB film) based on the individual query. CT urography (CTU) may be performed where specialised ultrasound or MR urography is unavailable.11 Childhood conditions that may require imaging by CT include three main areas: calculi, tumours and trauma (Table 78-5). TABLE 78-5 Indications for CT of the Renal Tract in Children Unenhanced CT has almost no role in paediatrics, except for calculi or calcifications,11 and these are best seen using ultrasound. Thus, standard non-ionic contrast medium (e.g. iohexol 300) is required at an age-adapted dose.11 Modern imaging techniques using automatic exposure control and low age-adapted kVp and size-based milliampere (mA)s settings will keep the dose to a diagnostic minimum, as will optimal age dependent timing delays and avoiding multiphase acquisitions. In cases of abdominal trauma, topographic delayed imaging after 10–15 min (or a split bolus technique) can be useful in selected cases to detect contrast medium extravasation from the genitourinary tract.12 Conventional cystography is preferred in suspected urethral injury. Figure 78-13 shows a normal CT urogram. Anatomical MRI is now the imaging modality of choice for abdominal and pelvic masses, as it gives excellent soft-tissue contrast resolution in any imaging plane, decreasing imaging times with modern equipment, improving tissue characterisation without the use of radiation. In most cases, MRI can replace CT, e.g. in the assessment of Wilms’ tumour, although thoracic CT may still be required to assess for pulmonary metastases. MRI can also give superior anatomical information to delineate pelvic anatomy, e.g. ambiguous genitalia, or where spinal MRI is needed to evaluate tumoural spread or suspected spinal cord abnormalities (neuropathic bladder). The most common use of MRI/MR urography (MRU) is to evaluate complex urinary tract malformations and urinary tract obstruction, having practically replaced IVU, e.g. Fig. 78-14.11 MRA is particularly useful to delineate the major renal vessels in preoperative (tumour) imaging, complicated hypertension, or as pre- or post-transplant assessment. The indications are given in Table 78-6. TABLE 78-6 Indications for MRI of the Renal Tract in Children Specific sequences and protocols are now available in most institutions for different clinical scenarios.13 Axial T1- and T2-weighted imaging are the mainstay of any imaging protocol, and either single-shot coronal heavily T2-weighted imaging or a 3D T2 sequence can give a ‘urogram’ overview of the entire urinary system (Fig. 78-15). Serial imaging following contrast enhancement is useful to delineate the enhancement of tumours, or arterial enhancement for anatomy. MRU is the only imaging modality to give detailed functional as well as anatomical detail. Full MRU requires a dedicated protocol, including hydration, sedation, catheterisation and diuresis, with prolonged T1 gradient-echo dynamic sequences demonstrating contrast uptake, elimination and drainage similar to radionuclide renograms. Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) is rapidly evolving to give an index of tumour cellularity (but does not differentiate benign from malignant tumours), identifying metastases, and in acute pyelonephritis and tumour treatment response. New techniques such as blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) MRI are being assessed to demonstrate changes in oxygenation of the kidney during acute obstructive episodes and in transplant imaging. Angiography is reserved for specific clinical situations (Table 78-7) by an experienced operator. Selective arteriography with magnification and oblique views is necessary to detect lesions in small renal vessels. TABLE 78-7 Indications for Angiography of the Renal Tract in Children This investigation should be carried out by an experienced operator in the radiology department or in theatre, usually before surgery, to provide anatomical detail of the renal pelvis and/or ureter unavailable from US or IVU. Occasionally antegrade studies are combined with pressure flow measurements with or without urodynamic studies to determine the physiological significance of a dilated upper urinary tract (the ‘Whitaker test’). The placement of a pigtail or J-J catheter in a dilated renal pelvis or ureter should be undertaken by an experienced operator under US guidance, with similar techniques to adults. US-guided needle placement into an appropriate lower pole calyx with contrast injection gives delineation of the collecting system before insertion of the tube. The complications of placing a nephrostomy tube are generally those of catheter placement, extravasation of contrast medium, and leakage of urine; thus, a combined sonographic–fluoroscopic approach is often recommended. The instillation of dilute contrast medium into a ureter via a catheter inserted into the distal ureteric orifice is usually undertaken by a urologist in the operating theatre. With modern flexible ureteroscopes, the contrast medium may be instilled into the upper ureter or even the renal pelvis, to outline the ureter and its drainage. Many disorders affecting the kidney need a biopsy for histological confirmation or diagnosis, particularly glomerular disease, nephrotic syndrome and IgA nephropathy. Surgical exploration or percutaneous US-guided needle biopsy should be considered, with complications such as subcapsular haematoma and AV fistula being fairly rare. Guidelines have recently been formulated for renal biopsy in children.14,15

Imaging of the Kidneys, Urinary Tract and Pelvis in Children

Overview

Imaging Techniques

Plain Radiography

Ultrasound

Standard Technique

Normal Gonadal Imaging in Girls

Normal Gonadal Imaging in Boys

Cystography

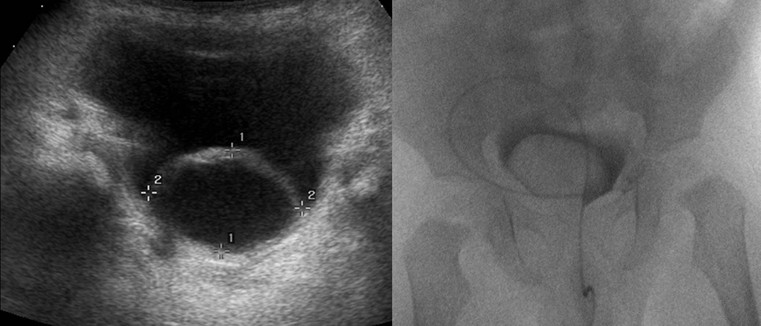

Micturating (Voiding) Cystogram (MCUG/VCUG)

Indications.

MCUG Technique.

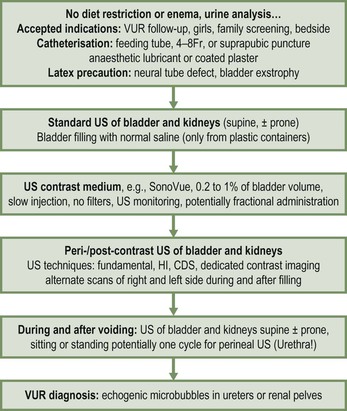

Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography (ce-VUS)

Technique.

Nuclear Medicine

Direct Radio-Isotope Cystogram (DIC)

Technique.

Indirect Radio-Isotope Cystogram

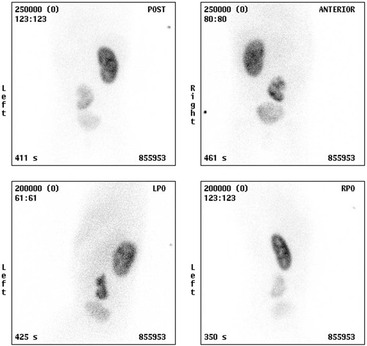

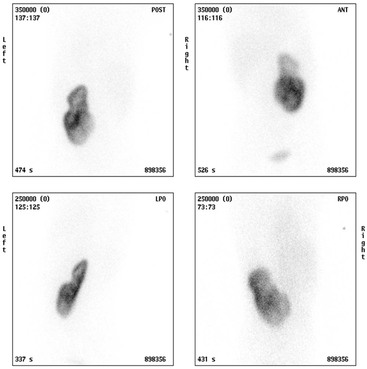

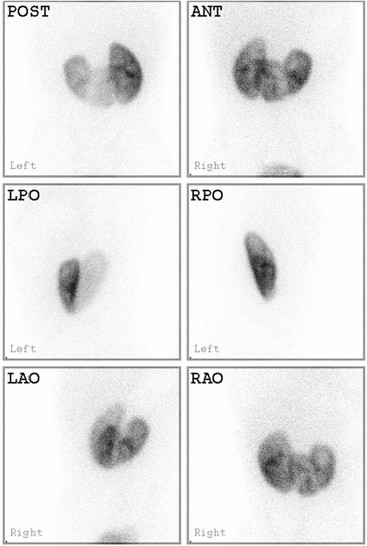

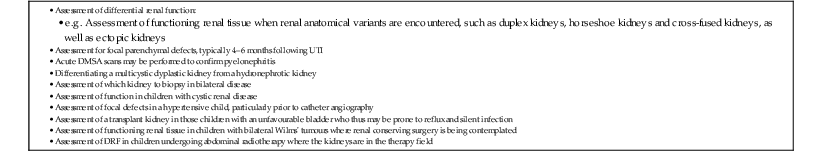

Static Renal Scintigraphy; 99mTc-DMSA Scans

Dynamic Renography

Technique.

Urography (Plain Radiograph and Intravenous Urogram)

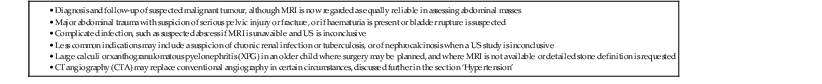

Computed Tomography

Method

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Method

Interventional Procedures

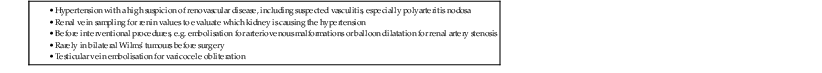

Angiography

Antegrade Pyelogram

Nephrostomy

Retrograde Pyelogram

Renal Biopsy

Congenital Anomalies

Renal Anomalies

Renal Agenesis

Unilateral agenesis occurs in approximately 1 in 1250 live births. Antenatal diagnosis is uncommon, suggesting that agenesis may be the result of an involuted multicystic dysplastic kidney.

Most functioning kidneys should be identifiable by US wherever they are located, and either 99mTc-DMSA or MR can be used to detect poorly functioning kidneys. VUR is more common in a non-functioning kidney, and associated ipsilateral abnormalities, including uterine/seminal vesicle or gonadal abnormalities are common, particularly easier to detect in the neonatal period before these structures involute physiologically.

Abnormal Migration and Fusion of the Kidneys

Appreciating renal embryology will assist in the understanding of the various forms of renal malformation and vascular anomalies. The kidney initially forms from an interaction between the mesonephric duct/ureteric bud and the metanephros at around 4 weeks of gestation. The primitive kidney ascends, rotating 90° from horizontal to medial, taking its blood from the aorta and draining via the inferior vena cava. An ectopic kidney may result from excess, incomplete or abnormal ascent. Abnormalities of fusion may occur if the kidneys touch each other in the process of ascending.

Renal Ectopia

Approximately 1 in 1000 kidneys is ectopic, and 10% are bilateral. The commonest is a pelvic kidney, which normally lies anterior to the sacrum just below the bifurcation of the aorta (Fig. 78-16). The true intrathoracic kidney (entering via the foramen of Bochdalek) is rare. Occasionally the kidney may be a superior ectopic kidney lying below a very thin membranous portion of the diaphragm. The adrenal glands are usually normally sited in the presence of renal ectopia, and there are many adrenal anomalies unrelated to renal variation.

Abnormalities of Renal Fusion

The commonest renal fusion abnormality is the horseshoe kidney. The lower poles of the kidneys are fused in the midline, possibly due to malposition of the umbilical arteries causing the developing nephrogenic masses to come together. The isthmus of the horseshoe commonly lies anterior to the aorta and vena cava, at the level of the inferior mesenteric artery, with malrotated collecting systems lying anteriorly, which may lead to pelviureteric junction obstruction and associated infections or calculi. The abnormal axis of the lower poles of the kidneys in a horseshoe should not be missed on US: if bowel gas obscures the anterior view, the loss of the normal medial renal contour and graded compression is useful, and the kidney itself can be used as a window to visualise the parenchymal bridge. The anterior view of a 99mTc-DMSA may be helpful to assess functioning renal tissue in a horseshoe. MRI also demonstrates abnormalities of renal and (often associated) vascular anatomy and their complications. The horseshoe kidney may become damaged in a road traffic accident because of the position of the lap belt in relation to the kidney. Power Doppler US provides excellent assessment of small traumatic lesions to a horseshoe kidney rather than resorting to CT. There is an increased risk of Wilms’ tumour in horseshoe kidneys and the anomaly may be associated with Edwards’ syndrome (trisomy 18) and Turner’s syndrome.

Cross Fused Renal Ectopia

Crossed fused renal ectopia is seen in 1 in 7000 post mortem examinations. The crossed ectopic kidney lies on the opposite side to its ureteral insertion into the bladder. The left kidney is more commonly the ectopic kidney and the commonest pattern is fusion of the upper pole of the crossed kidney with the lower pole of the normally positioned kidney, in an L shape (Fig. 78-17). Occasionally the crossed kidney remains unfused. Imaging by US demonstrates a unilateral large mass of renal tissue, with contralateral absence of renal tissue. Because of abnormalities in rotation, PUJO is common and a 99mTc-MAG3 (or dynamic MRU) study is often helpful in assessment of drainage, and VUR is common. Associated anomalies may be seen (for example, VACTERL association).

Duplex Kidneys

The commonest renal anomaly (2% of the population) is an uncomplicated duplex kidney. Complete duplication is caused by two separate ureteral buds presenting onto the mesonephric duct. The ureter draining the lower moiety will come to lie more superior to and lateral to the ureter draining the upper moiety, increasing the VUR risk to the lower moiety. The upper moiety ureteric insertion into the bladder usually is more distally and medially, may even be ectopic, or may be associated with an ureterocele, causing varying degrees of dysplasia and obstruction in the upper moiety (Fig. 78-18). Sometimes the upper moiety is difficult to see and if the upper moiety ureter drains ectopically into the vagina in a girl, continuous wetting or recurrent UTIs result. Careful interrogation by US, complemented by MRI, is essential in order to pick up both echogenic and atrophic upper moieties.

Incomplete ureteric duplication (‘incomplete duplication’) describes ureteric duplication above the bladder. Yo-yo VUR may be demonstrated by dynamic renography with tracer passing down one ureter and back up the partially duplicated second ureter into the respective renal moiety, but the kidney in these children looks the same as in a complete duplication. A ‘septated renal pelvis’ is the mildest variant of this condition. An ureterocele prolapsing into the vagina may present as a perineal mass in the newborn, or bladder outlet obstruction due to an ureterocole prolapsing into the posterior urethra (mimicking posterior urethral valves).

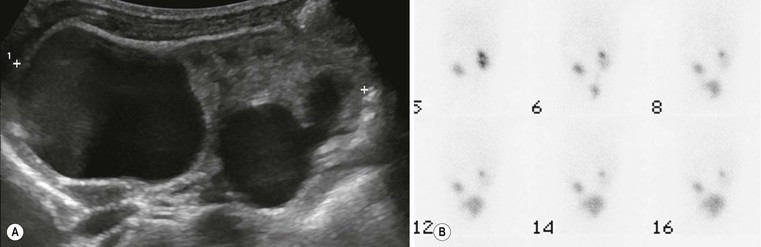

Imaging

A duplex kidney may be diagnosed by US, with a larger than normal kidney with two distinct collecting systems being separated by a bridge of renal tissue. The appearances of a duplex kidney vary with the pathology of each moiety. The upper moiety is usually dilated, particularly when associated with a ureterocele or ectopic ureteric insertion, or may be atrophic (Figs. 78-19 and 78-20). (Power) Doppler can estimate the degree of dysplasia and may demonstrate the ectopic ureteric jet. The lower moiety may be dilated in PUJO, or demonstrate scarring and uroepithelial thickening in the collecting system to indicate VUR.

The 99mTc-MAG3 will be helpful in assessment of renal function, scarring and dysplasia, allowing the relative contribution to function from each moiety to may be calculated. The uncomplicated duplex on a functional study may demonstrate up to 60% DRF compared to a simplex contralateral kidney, giving the false impression of reduced function in the simplex kidney. The axis of the duplex kidney on a DMSA may point towards the ipsilateral shoulder rather than the contralateral shoulder on the image, prompting the radiologist to look carefully on US for the hallmark finding of two separate collecting systems. The 99mTc-MAG3 renogram is also used to assess function and drainage in a complicated duplex kidney, and an IRC can be used in the toilet-trained child to assess for lower moiety VUR. Correct interpretation and calculations by scintigraphy rely heavily on accurate anatomical knowledge from US or MRI.

An MCUG can be useful both to assess for presence of possible ureterocele and for VUR into the lower moiety. Anatomical MR sequences can delineate the upper and lower poles, and MRU can help distinguish between an obstructed and non-obstructed dilated system. High-resolution isotropic 3D data sets may be reconstructed to clearly demonstrate ectopic insertion of the ureters, provided there is sufficient ureteral distension, dependent upon good hydration and bladder distension.

Anomalies of the Renal Pelvis and Ureter

US may demonstrate calyceal diverticulae or calyceal dilatation due to an infundibular stenosis, either congenital or acquired (secondary to infection or obstruction by calculi). MRI/MRU may further evaluate these appearances. Megacalycosis is a poorly understood condition where the dysplastic calyces are dilated in the absence of obstruction. It is probably due to underdevelopment of the medullary pyramids or maturation defects (resembling the shape of a pelvic kidney), and there may be an association with a megaureter and renal ectopia. Thus ureteric or pelvicaliceal dilatation does not indicate obstruction, and while the condition may predispose to stone formation, corrective surgery for ureteric dilatation is not beneficial.

Pelviureteric Junction Obstruction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree