Imaging of the pelvis can be required following minor or major trauma and for nontraumatic painful conditions. In this chapter, we review a systematic approach to interpretation of the standard pelvis x-ray, correlating abnormalities with computed tomography (CT) findings. We also discuss high-risk pelvic bony injuries associated with soft-tissue and vascular injuries—which are examined in detail in related chapters on genitourinary imaging ( Chapter 12 ), abdominal trauma ( Chapter 10 ), and interventional radiology ( Chapter 16 ). Because fractures of the proximal femur are often clinically indistinguishable from fractures of the pelvis, we illustrate these injuries here, with more discussion in the chapters on extremity injuries ( Chapter 14 ) and musculoskeletal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, Chapter 15 ). Along the way, we consider a number of critical clinical questions:

- 1.

How common are pelvic injuries?

- 2.

What injuries are associated with pelvic trauma?

- 3.

How dangerous are pelvic injuries?

- 4.

What are the techniques for pelvic x-ray and CT?

- 5.

How should x-ray and CT of the pelvis be interpreted?

- 6.

Who needs pelvic x-ray following trauma?

- 7.

When pelvic x-ray is normal, who needs CT?

- 8.

If CT is planned for evaluation of other abdominal and pelvic soft-tissue injuries, is x-ray needed? If so, in which patients?

- 9.

Why is MRI recommended for some injuries and CT for others?

- 10.

If CT is used in the setting of major trauma, why is MRI called upon for minor mechanisms of injury?

- 11.

What associated injuries must be suspected and evaluated when pelvic fractures are detected?

- 12.

What special imaging tests should be considered for pelvic fractures?

- 13.

What is the role of interventional radiology and angiographic embolization?

How Common Are Pelvic Injuries? What Injuries Are Associated With Pelvic Trauma?

An 8-year retrospective review of the trauma registry at the Los Angeles County and University of Southern California trauma center found that 9.3% of 16,630 adult admissions sustained some type of pelvic fracture. In patients with pelvic fractures, 16.5% had associated abdominal injuries, including liver (6.1%), bladder and urethra (5.8%), spleen (5.2%), diaphragm (2.1%), and small bowel (2%). In severe pelvic fractures (defined by an Abbreviated Injury Scale score ≥4), intrabdominal injuries rose in frequency to 30.7% of patients, and the bladder and urethra were most commonly injured, in 14.6% of patients. Aortic rupture was seven times more common in patients with pelvic fracture than in those without, although still rare (1.4%, compared with 0.2%).

How Dangerous Are Pelvic Injuries?

Mortality in patients with pelvic fractures is high—13.5% in adults in one large study. However, only about 0.8% of deaths are directly attributed to pelvic injuries. These are high-energy injuries that frequently coexist with severe injuries to the head, chest, abdomen, spine, and extremities. When pelvic injuries are noted on imaging studies, careful attention should be given to determining the presence of other injuries. The low mortality directly attributed to pelvic injuries should not suggest that these injuries themselves are unimportant. This low mortality is achieved when patients are treated at major trauma centers and receive aggressive therapy for pelvic injuries, including blood transfusion, orthopedic fixation, and angiographic embolization of pelvic vascular injuries. In one study, 38.5% of pelvic fracture patients received blood transfusion, with a mean transfusion of nearly 1 L. In severe pelvic fracture patients, 60.6% received transfusion, with a mean of more than 3.5 L. When severe pelvic injury was the only significant injury, more than 50% received transfusion, with a mean of 2.7 L. Overall, 16.6% of pelvic fracture patients required more than 2 L of blood in transfusion. Angiography (discussed in detail in Chapter 16 ) was performed in 4.7% of patients with pelvic injuries, and therapeutic embolization was performed in 2.3%, or half of those undergoing angiography.

Pelvic X-ray and Computed Tomography Techniques

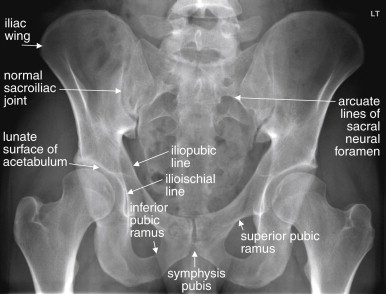

The routine initial view of the pelvis is the anterior–posterior (AP) x-ray ( Figure 13-1 ). This image is obtained with the patient supine and the x-ray beam oriented 90 degrees to the patient’s long axis, passing through the patient from anterior to posterior. Additional plain films can be obtained when injuries are seen on the AP image or if occult injuries are suspected with a normal AP view. These include oblique (Judet) views for characterization of acetabular fractures ( Figure 13-2 ), and inlet and outlet views for characterization of pelvic ring fractures ( Figure 13-3 ). Inlet views are obtained with the patient supine and the x-ray tube positioned at the patient’s head, angled 45 degrees toward the patient’s feet. This allows assessment of pelvic brim integrity, AP displacement of the hemipelvis, internal or external rotation of the hemipelvis, and anterior displacement of the sacrum. Outlet views are also obtained with the patient supine, with the x-ray tube at the patient’s feet and angled 45 degrees toward the head. This provides an excellent view of the sacrum, which is perpendicular to the x-ray beam in this position. The sacral neural foramina are seen well in this view, and vertical displacement of the hemipelvis may be evident. These additional views may be unnecessary if CT of the pelvis is planned, particularly if multiplanar two-dimensional images or three-dimensional models can be constructed, which depends on local software. Most modern picture archiving and communication system (PACS) software allows multiplanar two-dimensional reconstructions from multidetector CT image data, and three-dimensional capability is becoming routine. Three-dimensional reconstruction ( Figure 13-4 ) depends on high-quality original image data but is otherwise a postprocessing function and does not require a different CT protocol during the image acquisition phase.

Fracture detection with CT does not require the administration of IV or oral contrast. However, in most cases, IV contrast is given because the pelvic CT is obtained with the abdominal CT for detection of visceral injury. IV contrast allows recognition of active bleeding from pelvic vascular structures. Oral contrast is often not administered in the setting of trauma because it has little impact on diagnosis of bowel injuries (see the chapter on imaging of abdominal trauma, Chapter 10 ). A single CT scan of the pelvis can provide information about both soft-tissue and bony injuries. Urinary tract injuries require special CT techniques for diagnosis, as mentioned later and explored in more detail in the chapter on genitourinary imaging ( Chapter 12 ). When more detail of fractures is needed, fine-cut, dedicated “bony pelvis” CT can be performed without contrast, although not all injuries mandate this. In the past, dedicated bony pelvis CT was often obtained to characterize pelvic fractures in greater detail when fractures were seen on body CT performed for evaluation of visceral injury. Today, thin-slice multidetector body CT images offer good resolution of fractures, and bony pelvis CT may not be routinely required. CT images can be reconstructed in three dimensions for further characterization of fractures and dislocations (see Figure 13-4 ).

Interpretation of the Pelvic X-ray

The bony pelvis is a ring structure in which isolated fractures are rare. When reviewing a pelvic x-ray, detection of a single break in the ring mandates search for a second injury. Certain injury patterns are common, and detection of one component of a pattern logically guides your evaluation for the remaining components of the injury. In the figures that follow, a number of frequently encountered fracture patterns are described and illustrated. Figure 13-1 shows a normal pelvis x-ray with labels. Figures 13-5 to 13-19 show common patterns of injury schematically, with displaced fragments highlighted in dark gray. These injuries are also shown in actual x-rays and CTs in the figures that follow. In many cases, multiple injury types are present, so review the schematics first to understand the simplified key features of isolated injuries. Table 13-1 lists the injury patterns and associated figures in this chapter.

- 1.

Inspect the pubic symphysis for widening, overlap, or vertical dislocation, which may be seen the injury patterns described below. The normal pubic symphysis is usually about 4 to 5 mm in width and does not exceed 1 cm.

- 2.

Inspect the sacroiliac joints for widening, excessive overlap, or vertical off-set. The normal sacrum and iliac wing share a thin zone of overlap defining the sacroiliac joint. Widening of this joint space is abnormal and suggests joint injury and diastasis. The joints should be bilaterally symmetrical. The normal sacroiliac joint is 2 to 4 mm in width.

- 3.

Examine the sacrum for fractures, which may intersect the normal neural foramina. If the sacroiliac joints are intact but the right and left pelvis are malaligned vertically, suspect a vertically oriented sacral fracture.

- 4.

Follow the ring formed by the inferior portion of the sacrum and the medial portion of the ilium and ischium, sweeping down the pubic bone to the pubic symphysis and back up the opposite side to your starting point. This should form a smooth continuous ring without cortical irregularities.

- 5.

Inspect the smaller ring formed between the inferior and superior pubic rami, called the obturator foramen. This should be a smooth continuous circle. The opposite side usually provides an excellent comparison view, unless bilateral injuries are present. Inspect the superior and inferior pubic rami for discontinuities.

- 6.

Inspect the iliac wings for fractures. Overlying bowel gas may create rounded lucencies overlying the iliac bones, whereas linear lucencies are more suggestive of fracture. Follow lucencies to determine whether they intersect the outer border of the iliac bones, which should be smooth continuous curves without cortical stepoffs.

- 7.

Inspect the acetabula bilaterally, noting whether the femoral heads are located appropriately or dislocated. The curved concave surface of the acetabulum, called the lunate surface, should be a smooth continuous curve, matching the curve of the femoral head. Clues to acetabular fractures include disruption of the iliopubic line, ilioischial line, and lunate surface. The joint spaces separating the femoral head and lunate surface of the acetabulum should be bilaterally symmetrical.

- 8.

Inspect the femur, including the femoral head, neck, and intertrochanteric region, as these are common sites of fracture, particularly in elderly patients.

| Content | Figure Number |

|---|---|

| Approach to pelvic image interpretation | |

| 13-1, 13-5 |

| 13-2 |

| 13-3 |

| 13-4 |

| 13-5 to 13-19 |

| Pelvic ring pathology | |

| 13-6, 13-20 to 13-30 |

| 13-7 to 13-10, 13-36 to 13-41 |

| 13-12, 13-31 to 13-35 |

| 13-38 |

| 13-8, 13-9, 13-12, 13-13, 13-31, 13-33, 13-39, 13-40, 13-44, 13-51, 13-55 to 13-57 |

| 13-10, 13-11, 13-40, 13-41, 13-52 to 13-54 |

| 13-14, 13-28, 13-31, 13-32, 13-43 |

| 13-42 |

| 13-30 |

| Injuries of the hip | |

| 13-15, 13-28, 13-29, 13-43 to 13-46, 13-48 to 13-50, 13-62, 13-64, 13-65 |

| 13-4, 13-16, 13-62 to 13-65 |

| 13-17, 13-34, 13-66, 13-67 |

| 13-68 |

| 13-18, 13-69, 13-70 |

| 13-19, 13-71 |

| 13-72, 13-73 |

| 13-74 |

| Low-mechanism pelvic injuries | |

| 13-58 |

| 13-59 |

| 13-60, 13-61 |

| |

| 13-75, 13-76 |

| 13-77 to 13-79 |

We begin with the normal AP pelvis x-ray (labeled, see Figure 13-1 ). Each structure examined on x-ray should also be reviewed when interpreting CT scan. Stepwise inspection of the AP pelvic x-ray should include evaluation of the following (see Figure 13-5 ):

- 1.

Inspect the pubic symphysis for widening, overlap, or vertical dislocation, which may be seen with the injury patterns described later. The normal pubic symphysis is usually about 4 to 5 mm in width and does not exceed 1 cm. Figures 13-6 and 13-7 illustrate some common patterns of abnormality of the symphysis pubis.

- 2.

Inspect the sacroiliac joints for widening, excessive overlap, or vertical offset. The normal sacrum and iliac wing share a thin zone of overlap defining the sacroiliac joint on the AP view. Widening of this joint space is abnormal and suggests joint injury and diastasis. The joints should be bilaterally symmetrical. The normal sacroiliac joint is 2 to 4 mm in width. Figures 13-6 to 13-9 show abnormal sacroiliac joints.

- 3.

Examine the sacrum for fractures, which may intersect the normal neural foramina. If the sacroiliac joints are intact but the right and left pelvis are malaligned vertically, suspect a vertically oriented sacral fracture. Transverse sacral fractures may sometimes occur in isolation and may not disrupt the integrity of the pelvic ring. Figures 13-10 and 13-11 depict sacral fractures.

- 4.

Follow the ring formed by the inferior portion of the sacrum and the medial portion of the ilium and ischium, sweeping down the pubic bone to the pubic symphysis and back up the opposite side to your starting point. This should form a smooth, continuous ring without cortical irregularities. Figures 13-6 to 13-13 show abnormalities in this contour associated with different fracture patterns.

- 5.

Inspect the smaller ring formed between the inferior and the superior pubic rami, called the obturator foramen. This should be a smooth, continuous circle. The opposite side usually provides an excellent comparison view, unless bilateral injuries are present. Inspect the superior and inferior pubic rami for discontinuities. Figures 13-8, 13-9, 13-12, and 13-13 show fractures involving the pubic rami and obturator foramen.

- 6.

Inspect the iliac wings for fractures. Overlying bowel gas may create rounded lucencies overlying the iliac bones, whereas linear lucencies are more suggestive of fracture. Follow lucencies to determine whether they intersect the outer border of the iliac bones, which should be smooth, continuous curves without cortical step-offs. Figure 13-14 depicts an isolated iliac wing fracture.

- 7.

Inspect the acetabula bilaterally, noting whether the femoral heads are located appropriately or dislocated. The curved concave surface of the acetabulum, called the lunate surface, should be a smooth, continuous curve, matching the curve of the femoral head. Clues to acetabular fractures include disruption of the iliopubic line, ilioischial line, and lunate surface ( Figure 13-15 ). The joint spaces separating the femoral head and lunate surface of the acetabulum should be bilaterally symmetrical. Figures 13-16 and 13-17 depict posterior and anterior dislocations of the femoral head (hip).

- 8.

Inspect the femur, including the femoral head, neck, and intertrochanteric region because these are common sites of fracture, particularly in elderly patients. Figures 13-18 and 13-19 illustrate some common patterns of proximal femur fracture.

Patterns of Pelvic Injury

Fractures of the pelvis can range from innocuous, requiring no treatment, to immediately life threatening. Their appearance on x-ray can be subtle or overt, and the emergency physician must be able to recognize key injuries immediately to take appropriate stabilization measures, plan interventions such as angiographic embolization, consider additional imaging, and arrange safe disposition. We examine a number of common fracture patterns, recognizing that often a mixture of injury patterns may be present in the same patient.

Two major systems of classification of pelvic fractures are the Young-Burgess classification and the Tile classification systems ( Tables 13-2 and 13-3 ). The Young-Burgess classification describes injuries in terms of mechanism and type of injury, direction of hemipelvis displacement, and stability. The Tile classification divides fractures into three main categories, each with multiple subtypes, including stable fractures with an intact posterior arch (type A), unstable anterior and lateral compression fractures with incomplete disruption of the posterior arch (type B), and vertical shear injuries with complete disruption of the posterior arch (type C). While these are useful for orthopedists in surgical planning, emergency physicians can understand injuries and communicate them clearly to specialty colleagues with simple descriptions, based on recognition of several common injury patterns.

| Classification (Based on injury Mechanism, Hemipelvis Displacement, and Stability) | Characteristics | Stability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP compression with external rotation of hemipelvis | Type I | Pubic diastasis <2.5 cm | Stable |

| Type II | Pubic diastasis >2.5 cm and anterior sacroiliac joint disruption | Rotationally unstable, vertically stable | |

| Type III | Type II plus posterior sacroiliac joint disruption | Rotationally and vertically unstable | |

| Lateral compression with internal rotation of hemipelvis | Type I | Ipsilateral sacral buckle fractures or ipsilateral horizontal pubic rami fractures (or disruption of symphysis pubis with overlapping pubic bones) | Stable |

| Type II | Type I plus ipsilateral iliac wing fracture or posterior sacroiliac joint disruption | Rotationally unstable, vertically stable | |

| Vertical shear with cranial–caudal displacement of hemipelvis | Vertical pubic rami fractures and sacroiliac joint disruption with or without adjacent fractures | Rotationally and vertically unstable | |

| Classification | Characteristics | Hemipelvis Displacement | Stability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A—posterior arch intact | A1—pelvic ring fracture (avulsion) | A1.1 | Anterior iliac spine avulsion | None | Stable |

| A1.2 | Iliac crest avulsion | ||||

| A1.3 | Ischial tuberosity avulsion | ||||

| A2—pelvic ring fracture (direct blow) | A2.1 | Iliac wing fracture | |||

| A2.2 | Unilateral pubic ramus fracture | ||||

| A2.3 | Bilateral pubic rami fracture | ||||

| A3—transverse sacral fracture | A3.1 | Sacrococcygeal dislocation | |||

| A3.2 | Nondisplaced sacral fracture | ||||

| A3.3 | Displaced sacral fracture | ||||

| Type B—incomplete posterior arch disruption | B1—AP compression | B1.1 | Pubic diastasis and anterior sacroiliac joint disruption | External rotation | Rotationally unstable, vertically stable |

| B1.2 | Pubic diastasis and sacral fracture | ||||

| B2—lateral compression | B2.1 | Anterior sacral buckle fracture | Internal rotation | ||

| B2.2 | Partial sacroiliac joint fracture or subluxation | ||||

| B2.3 | Incomplete posterior iliac fracture | ||||

| B3.1—AP compression | B3.1 | Bilateral pubic diastasis and bilateral posterior sacroiliac joint disruption | External rotation | ||

| B3.2—AP and lateral compression | B3.2 | Ipsilateral B2 injury and contralateral B1 injury | Ipsilateral internal rotation and contralateral external rotation | ||

| B3.3—bilateral lateral compression | B3.3 | Bilateral B2 injury | Bilateral internal rotation | ||

| Type C—complete posterior arch disruption | C1—vertical shear | C1.1 | Displaced iliac fracture | Vertical | Rotationally and vertically unstable |

| C1.2 | Sacroiliac joint dislocation or fracture and dislocation | ||||

| C1.3 | Displaced sacral fracture | ||||

| C2—vertical shear and AP or lateral compression | C2 | Ipsilateral C1 injury and contralateral B1 or B2 injury | Ipsilateral vertical (cranial) and contralateral internal or external rotation | ||

| C3—bilateral vertical shear | C3 | Bilateral C1 injury | Bilateral vertical (cranial) | ||

Two primary categories of injury should be considered from an emergency medicine perspective: fractures that disrupt the major pelvic ring and those that do not. Fractures that compress or open the pelvis ring can disrupt blood vessels passing through the pelvis. In addition, because they change the geometry of the pelvis from a stable cone with a fixed volume to an expandable structure with the ability to increase in size, substantial bleeding can occur in the pelvis from these fracture types. Identification of a fracture in this group should prompt pelvic stabilization, preparation for potentially massive transfusion, and consideration of angiographic embolization. Fractures that do not affect the pelvic ring in this way can be important for other reasons, but rarely are they as immediately life-threatening. For example, fractures near the pubic symphysis involving the inferior or superior pubic rami may be associated with bladder and urethral injuries, as well as vaginal lacerations in female patients. Acetabular fractures, while associated with disability from posttraumatic arthritis, do not pose an immediate life-threat to the patient.

Forces That Disrupt the Major Pelvic Ring

Fractures that affect the stability of the pelvic ring can be subcategorized in several additional ways—for example, by mechanism of injury. In theory, fractures that compress the pelvic ring laterally may be less likely to stretch and tear vascular structures, compared with structures that involve AP compression, opening the pelvis at the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joints. Vertical shear injuries to the pelvis may disrupt vascular structures and result in damage to nerve roots at the level of the sacrum. Important pelvic ring disruptions involve fractures or diastasis of joints at two or more sites of the anterior and posterior pelvic arcs. Separation of the pubic symphysis and diastasis of the sacroiliac joints can cause pelvic ring disruption in the absence of a fracture. Two or more fractures can also result in pelvic ring disruption. A combination of one fracture and one diastatic joint may also occur. Because the bony pelvis is a ring, a single disruption usually does not occur; rather, a disruption in one location results in fracture or diastasis at a second point in the ring. When one disruption in the pelvis ring is seen, a second should be suspected and sought. Sometimes the second disruption is at the pubic symphysis or sacroiliac joint and may be unapparent on x-ray because these joints can open and close with repositioning of the patient once the joint has been destabilized.

Anterior-posterior compression injuries

AP compression of the pelvic ring typically separates the pubic symphysis anteriorly while opening the sacroiliac joint posteriorly ( Figures 13-20 to 13-30 ; see also Figure 13-6 ). This fracture pattern is often called an open-book pelvic fracture and can be a life-threatening injury. It results from substantial force and can shear pelvic veins and arteries. Significant bleeding into the pelvis often occurs with this injury. Because this injury increases the volume of the potential space within the pelvis, tamponade of bleeding does not occur, and the patient’s entire blood volume can be accommodated within the pelvis. When this injury is recognized on x-ray or on CT scan, the pelvis should be closed using some type of external compression device. Urethral injuries are also associated with this type of pelvic injury. Evaluation of urethral injury is discussed in detail in the chapter on the genitourinary system ( Chapter 12 ).