Imaging of soft tissues of the neck can be essential in the evaluation of patients with a variety of chief complaints, including neck trauma, ingested or aspirated foreign body, nontraumatic neck pain and swelling, dysphagia and voice change, visible or palpable mass, and central nervous system complaints with possible vascular causes. The neck contains vascular, nerve, airway, gastrointestinal, and bony structures, any of which may be the source of pain. Remember that referred pain from other regions of the body may present with neck pain, so a broad differential diagnosis should be entertained in formulating an imaging plan. Fascial planes connect compartments of the neck with the mediastinum and thoracic prevertebral spaces, posing a risk of spread of infection from the neck to these regions. Imaging of the neck often is performed with imaging of the head or chest, as structures passing through the neck extend into these adjacent body regions. In this chapter, we explore the modalities available for soft-tissue cervical imaging, discuss clinical indications for imaging in a variety of chief complaints, and review some characteristic findings of important pathology, using the figures throughout the chapter. Imaging of the soft tissues of the cervical spinal cord and ligaments are discussed in Chapter 3 .

Who Needs Soft-Tissue Imaging? Which Imaging Modality Should Be Used?

Given the range of potential pathology discussed earlier, it should come as little surprise that no single clinical decision rule can be used to inform decisions for soft-tissue neck imaging. Instead, the differential diagnosis under consideration should drive the imaging decision, based on expected features of the pathology and the capabilities of each modality. Dilemmas for the practitioner include whether imaging is required and, if so, whether to screen with a limited test such as x-ray, rather than incurring the additional cost and radiation exposure of computed tomography (CT). Some soft-tissue neck abnormalities are best assessed with neither x-ray nor CT but rather with ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluoroscopy, or techniques such as bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy. First we consider some general principles regarding the available imaging modalities: x-ray, CT, ultrasound, and MRI. Fluoroscopy is discussed later with regard to esophageal pathology.

Soft-Tissue X-ray of the Neck

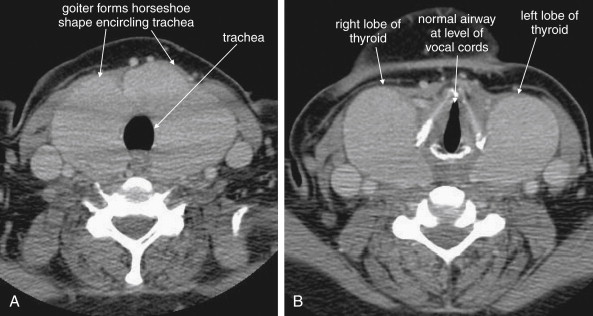

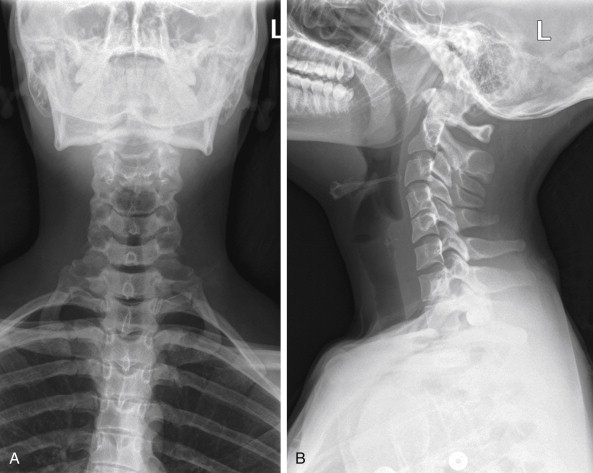

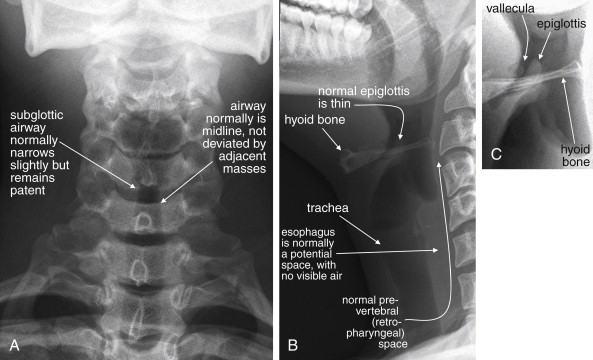

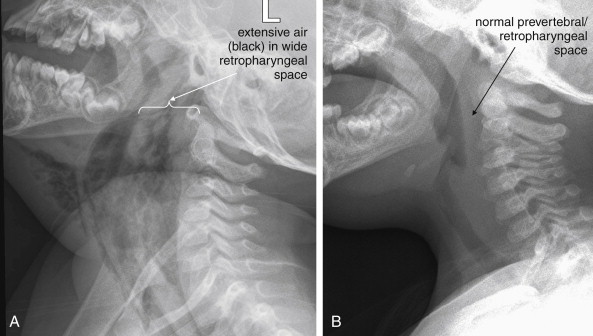

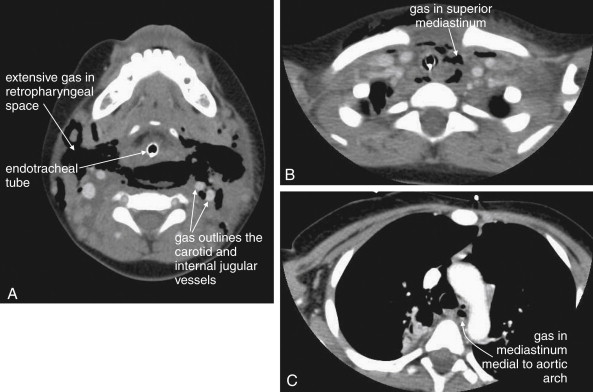

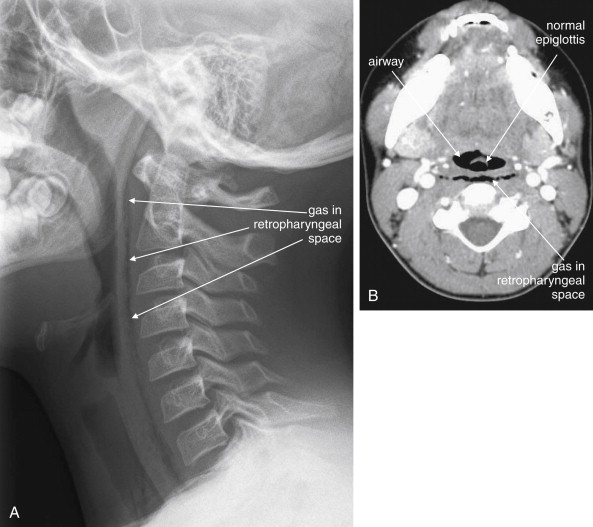

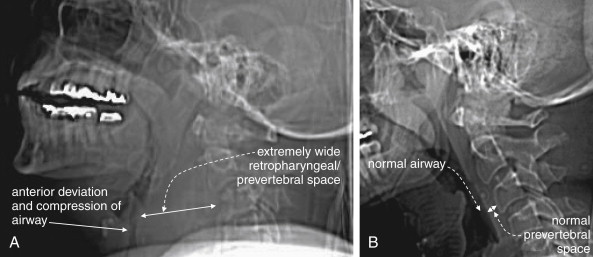

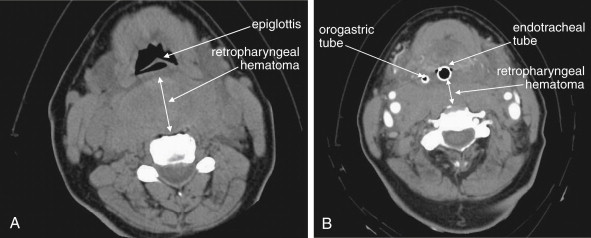

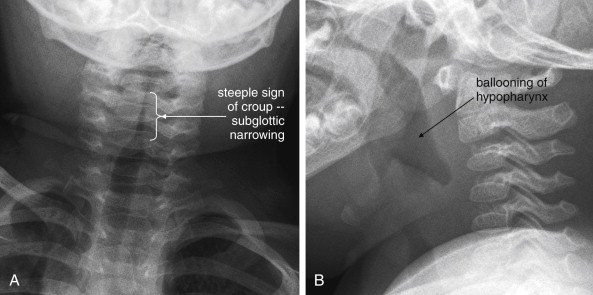

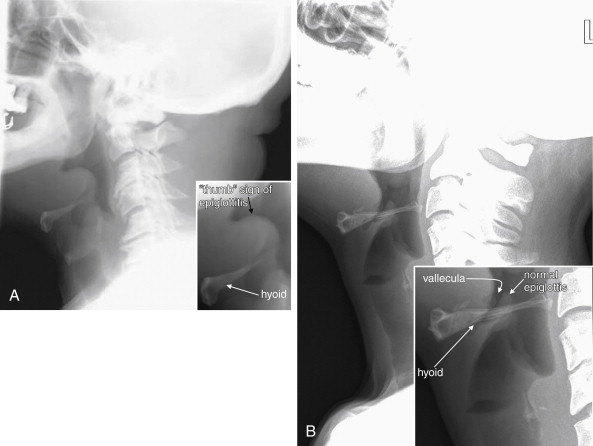

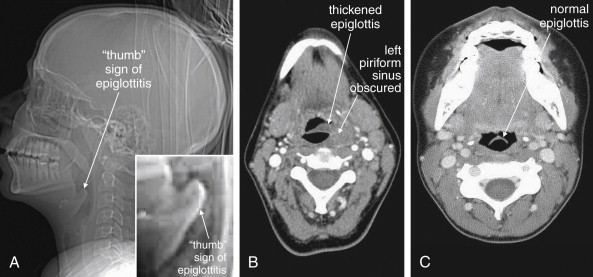

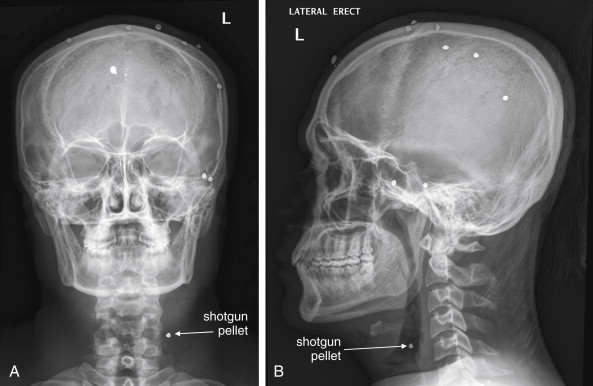

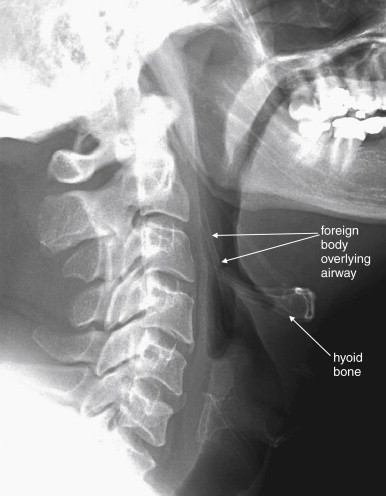

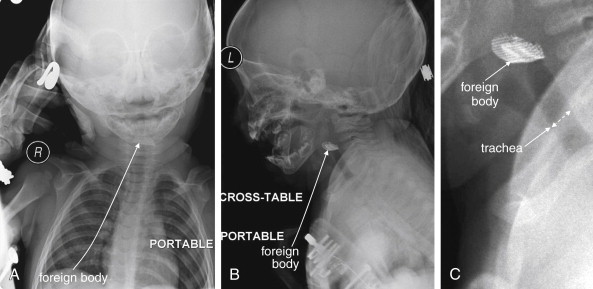

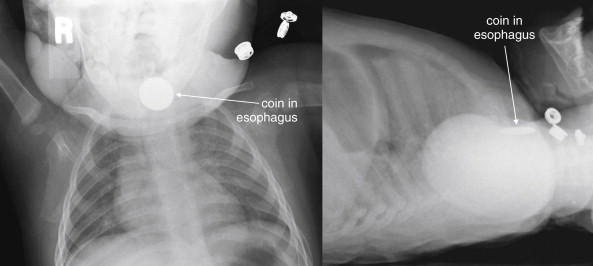

Plain x-ray ( Figures 4-1 and 4-2 ) provides limited information about the soft tissues of the neck. X-ray relies on differentiation of adjacent structures using four basic tissue densities: air, fat, water (which includes soft tissues, both solid organs such as muscle and fluids such as blood), and bone (sometimes called metal density ). As we discuss in detail in Chapter 5 with regard to chest x-ray, two adjacent structures with the same basic tissue density are indistinguishable on x-ray; no border is seen separating them. When two tissues of different density abut one another, the transition is clear. For this reason, x-rays can demonstrate abnormal soft-tissue air ( Figures 4-3 to 4-5 ), deviation or compression of normal air-filled structures (the trachea particularly) ( Figures 4-3 and 4-6 to 4-10 ), air–fluid levels suggesting abscess, and radiopaque foreign bodies ( Figures 4-11 to 4-15 ), as all of these involve a contrast between two key tissue densities. Unfortunately, many of the soft-tissue abnormalities of interest to us as emergency physicians may not involve such a contrast. Instead, one soft-tissue structure may abut a second soft-tissue structure, and these are indistinguishable on x-ray. This leaves an array of potentially devastating forms of neck pathology that are poorly assessed with x-ray. Examples include vascular dissections, abscesses, and subtle soft-tissue masses that may not be seen on x-ray.

What Information Can Be Gleaned from a Portable Soft-Tissue Neck X-ray? How Should It Be Interpreted?

Portable anterior–posterior (AP) and lateral soft-tissue neck x-rays provide basic information about the airway, as described earlier. Like a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST), the soft-tissue neck film should be assessed by the emergency physician with several specific clinically relevant questions in mind. As you interpret an x-ray, ask yourself each of these questions, rather than simply looking at the x-ray, and assess the x-ray for relevant findings.

On the AP x-ray:

- 1.

Is the airway deviated laterally or narrowed, suggesting an extrinsic mass?

- 2.

Is the airway narrowed by concentric inflammation, producing a “steeple sign” characteristic of croup (see Figure 4-8 )?

- 3.

Is air visible in the soft tissues of the neck, indicating potential pneumomediastinum, prevertebral air, esophageal or tracheal perforation, or retropharyngeal abscess?

- 4.

Is a radiopaque foreign body visible (see Figures 4-11 and 4-14 )?

On the lateral x-ray:

- 1.

Is the airway deviated or narrowed in the AP direction? If so, why? Is an anterior neck mass compressing the trachea, or is a retropharyngeal process exerting a mass effect ( see Figure 4-6 )?

- 2.

Are the soft tissues directly behind the trachea in the retropharyngeal and prevertebral spaces thickened? If so, do they impinge upon the airway (see Figures 4-3, 4-5, and 4-6 )? The normal thickness of prevertebral spaces has been reported in several studies, using both x-ray and CT ( Table 4-1 ).

TABLE 4-1

Normal Prevertebral Soft-Tissue Thickness

Imaging Modality and Location

Thickness

X-ray

Retrocricoid soft-tissue thickness (x-ray)

0.7× diameter of C5 vertebral body

Retrotracheal soft-tissue thickness (x-ray)

1.0× diameter of C5 vertebral body

CT

C1

8.5 mm

C2

6 mm

C3

7 mm

C4-5

Not determined because of variable position of esophagus and larynx

C6

18 mm

C7

18 mm

From Chen MY, Bohrer SP. Radiographic measurement of prevertebral soft tissue thickness on lateral radiographs of the neck. Skeletal Radiol 1999;28(8):444-6; Rojas CA, Vermess D, Bertozzi JC, et al. Normal thickness and appearance of the prevertebral soft tissues on multidetector CT. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 30(1):136-41, 2009.

- 3.

Is an air–fluid level present posterior to the trachea, representing an abscess that could rupture into the airway or extrinsically compress it?

- 4.

Is the epiglottis enlarged, threatening supraglottic airway obstruction from epiglottitis ( see Figures 4-9 and 4-10 )?

- 5.

Is abnormal air visible in the neck, indicating potential pneumomediastinum, prevertebral air, esophageal or tracheal perforation, or retropharyngeal abscess (see Figures 4-3 and 4-5 )?

- 6.

Is a radiopaque foreign body visible (see Figures 4-11 and 4-13 to 4-15 )?

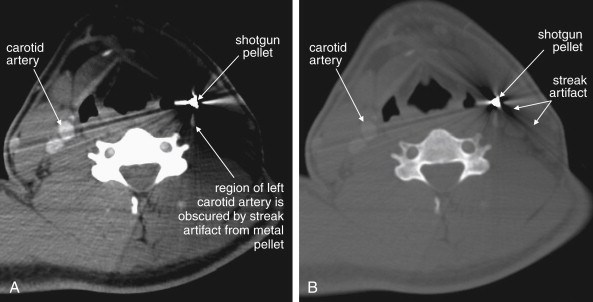

Soft-Tissue Neck CT

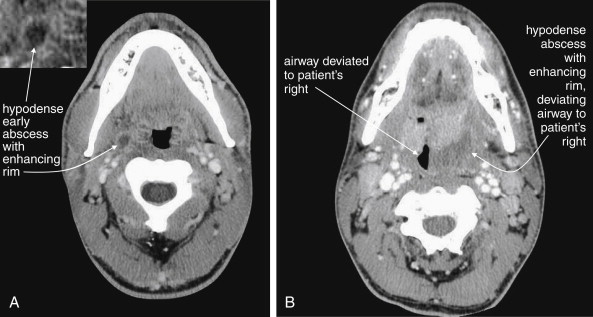

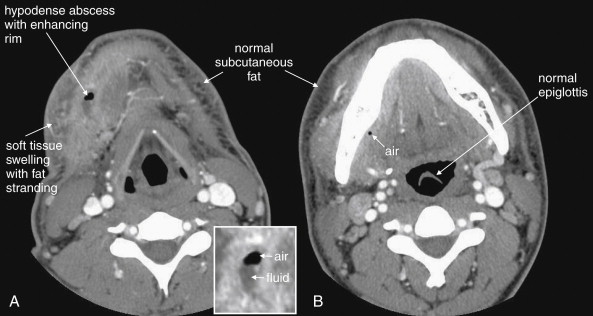

CT is clearly superior to x-ray, as it is able to distinguish a subtler spectrum of tissue densities. CT scan readily distinguishes air, fat, fluid, solid soft tissues of muscle density, and bone. The window setting on CT (discussed in detail later) can be adjusted to highlight a particular tissue density, but on all window settings these tissues are color coded from black (lowest density) to white (highest density). On soft-tissue windows, which are key in our evaluation of neck soft-tissue pathology, air is black, fat is a dark gray (nearly black), fluids such as blood or pus are an intermediate gray, solid tissues are a slightly lighter gray, and high-density material such as bone or metal are white. Lung window settings are sometimes used to evaluate the neck, as air becomes quite evident (black) against all other tissue densities, which appear white on this window setting. Bone windows also highlight air (black) in contrast to all other tissues. Nonstandard window settings can be selected to highlight pathology. The precise density of a tissue can also be measured on CT scan on most picture archiving and communication systems (PACSs) (the name given to a digital diagnostic imaging interface). The computer cursor can be placed over a single pixel or a broader region of interest, and the density of the tissue in Hounsfield units (HU) is reported. On the Hounsfield scale (Figure 000), water has a density of 0 HU, air has a density of −1000 HU, and the highest-density bone has a density of +1000 HU. Nonbiological high-density substances such as metal foreign bodies have densities exceeding +1000 HU. Fat is less dense than water and has a lower density, around −50 HU. Soft tissues such as muscle are denser than water and have a higher Hounsfield value, around 30–50 HU. Liquid blood has a density slightly greater than water, due to its cellular content; the density may vary with factors such as hematocrit and volume status. CT allows ready identification of a tissue abnormality such as abscess based on density differences. An abscess ( Figures 4-16 and 4-17 ) filled with liquid pus appears darker than denser surrounding soft tissues viewed on soft-tissue windows.

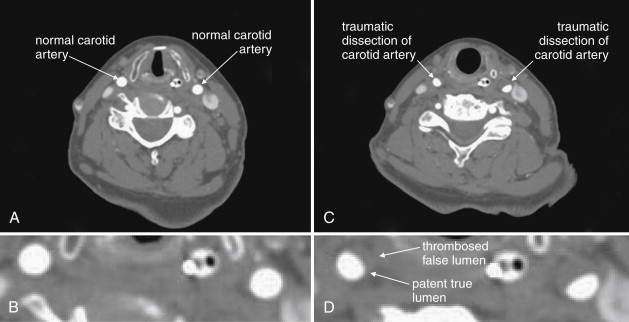

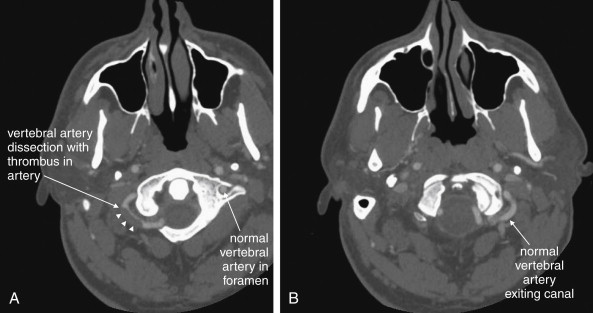

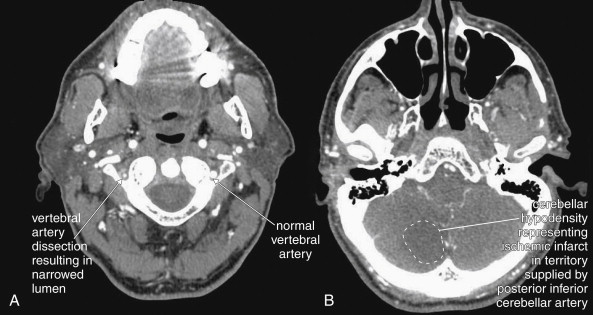

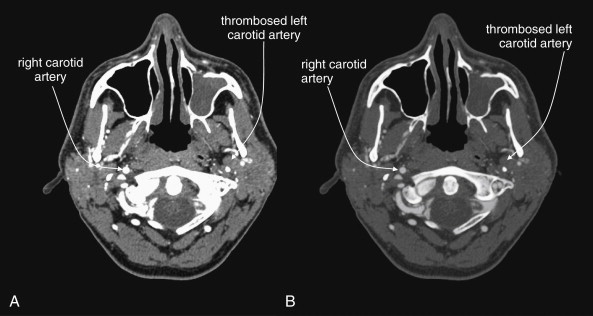

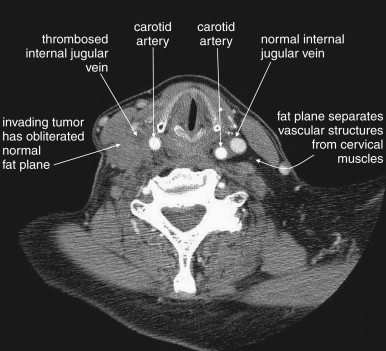

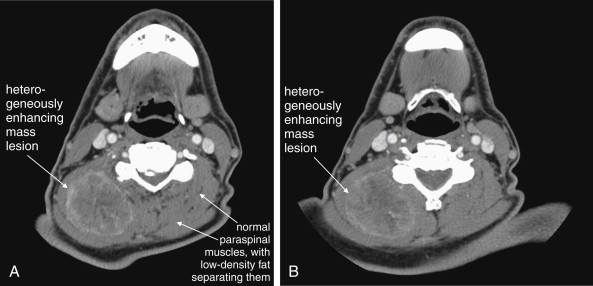

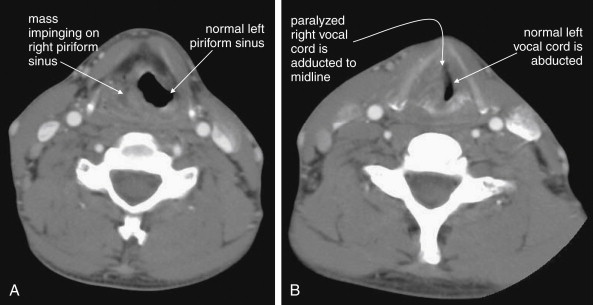

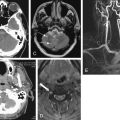

Structures with identical (or nearly identical) density are indistinguishable on CT without contrast, with several clinically important examples. Because pus is similar in density to surrounding normal soft tissues, IV contrast can assist in identifying an abscess. Normal soft tissues are highly vascular and enhance (increase in density) following administration of IV contrast. Pus within an abscess does not enhance with IV contrast, so the difference in density between abscess and normal surrounding tissues increases following IV contrast administration, increasing the conspicuity of the abscess. Similarly a vascular dissection ( Figures 4-18 to 4-20 ) would be difficult or impossible to recognize without contrast, because blood in the true and false lumen share the same density, and the thin intimal flap separating them is of nearly identical density. Administration of intravenous (IV) contrast changes this relationship by providing high-density (contrast) material flowing on both sides of the intimal flap. The low-density flap becomes visible against this background. Partially thrombosed vascular segments ( Figures 4-21 to 4-22 ), which are common in dissections of the relatively small-caliber vessels of the neck, are also made visible by this same principle: high-density contrast flows through the patent lumen of the vessel, making low-density thrombus visible. Without contrast, liquid blood and thrombus share nearly identical densities and are nearly indistinguishable. Contrast also aids in detecting soft-tissue masses. Normal muscle and a muscle tumor such as sarcoma ( Figures 4-23 to 4-25 ) may share the same tissue density without contrast. However, a highly vascular neoplasm receives differentially more parenterally administered contrast and has a higher density when imaged with contrast. CT does not perfectly distinguish benign and malignant mass lesions, so biopsy is necessary for confirmation. Even when an abscess is not present, inflamed or infected soft tissues also have increased blood flow and enhance with IV contrast ( Figure 4-26 ; see also Figures 4-16, 4-17, and 4-26 ). Without any contrast administration, CT is excellent for airway assessment, as very low-density air within the airway provides outstanding intrinsic contrast against surrounding soft tissues. ( Figure 4-27 ; see also Figures 4-7, 4-10, 4-16, 4-17, 4-24, and 4-25 ). However, extreme caution should be applied in sending patients with suspected airway pathology to CT, as airway obstruction can be worsened by supine positioning for CT.