Implementing Ultrasound in Developing Countries

Sachita Shah

INTRODUCTION

With improvements in portability, durability, and affordability, clinician-performed ultrasound has reached the bedside of the world’s most vulnerable populations in the developing world. An ever-expanding body of literature has grown to support the use of bedside, point-of-care ultrasound performed by nonradiologist physicians, nurses, and clinical officers in developing nations in clinical patient care (1). Given the worldwide lack of radiology services, and increased recognition of downside risks to imaging-related radiation, it is arguably more important than ever before to increase access to ultrasound services in the developing world through improved delivery of appropriate ultrasound equipment and training programs. This chapter will review existing evidence to support ultrasound use in low-resource settings, suggest strategies and models for implementing an ultrasound program in a developing world setting, and review ultrasound findings of commonly observed disease processes in these settings.

Emergency physicians are poised to be leaders in the field of bedside ultrasound in low-resource settings for many reasons. As an integral part of emergency medicine residency training, point-of-care ultrasound is a skill that our specialty has recognized as easily imparted through appropriate training and easily incorporated into routine care of a diverse patient population (2). Because emergency physicians are comfortable with a variety of patient types and disease processes, they are potentially better able to help generalist health care providers in the developing world integrate their ultrasound skills into the day-to-day care of their patients. Goal-directed, focused bedside ultrasound exams are ideal for providing immediate information to guide clinical care in both a bustling American emergency department (ED) and a busy practice in an underserved international setting for similar reasons.

EXISTING LITERATURE

Increased recognition of the importance of ultrasound in the developing world is seen through a growing body of literature, including clinical handbooks and in-field research (3, 4, 5). Descriptive experiences of the value of bedside ultrasound in both developing nations and disaster settings are plentiful, but a handful of studies examine the impact of ultrasound on clinical management and outcomes. Small studies from Rwanda (6), Liberia (7), and the Amazon jungle (8) show that clinician-performed ultrasound changed the differential diagnosis and changed the management plans or disposition in 28% to 72% of patients. These results are echoed in larger studies such as the review by Steinmetz et al. examining data from 1119 ultrasound scans performed in western Cameroon, in which ultrasound not only provided the diagnosis in 31.6% of patients and changed the differential diagnosis in 36.2% of patients, but also expanded the differential diagnosis appropriately to include the true disease process, which had not been previously considered in a large number of patients (9). These studies also suggest that

ultrasound findings in the developing world are most often abnormal, suggesting that a high rate of pathology is visualized by bedside ultrasound.

ultrasound findings in the developing world are most often abnormal, suggesting that a high rate of pathology is visualized by bedside ultrasound.

Specific research from developing world settings on use of ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology suggests a very high impact can be made in this specific patient population (10, 11, 12, 13), specifically with regard to conditions that may lead to preterm or complicated birth, and postpartum hemorrhage. Studies from several African countries suggest that ultrasound by trained practitioners can aid in diagnosis of abnormal fetal presentation, intrauterine growth retardation, multiple gestation, placental issues, fetal heart rate, and estimation of gestational age. Other research suggests that nonphysicians can be trained to perform basic obstetrical ultrasound, including determination of gestational age, with a high degree of accuracy and inter-rater reliability compared with trained sonographers (14,15). While estimation of gestational age in the second and third trimester using fetal biometry is not frequently performed by emergency physicians, it is an easily learned skill that can then be transferred in a training program for low-resource settings (16).

Uses of portable ultrasound for echocardiography in resource-poor settings have also been explored with interesting results. Studies suggest handheld echocardiography in the developing world can aid in diagnosis and workup of patients presenting with murmurs, severe hypertension, edema, pain, and dyspnea, including diagnoses such as ventricular systolic dysfunction, left ventricular hypertrophy, congenital abnormalities, significant rheumatic valvular disease, and pericardial effusion (17,18).

A small number of descriptive studies and a single text demonstrate the use of ultrasound in patients with infectious diseases prevalent in the developing world, including HIV and tuberculosis (TB) (19). Specifically, HIV-infected patients appear to suffer from cardiomyopathy, nephropathy, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, retroperitoneal and mesenteric lymphadenopathy, ascites, and biliary abnormalities at a higher rate than their non-HIV-infected matched controls (20). Abdominal TB with ascites is a commonly encountered diagnostic query that is difficult to distinguish from cirrhosis with ascites by physical exam alone. A study of Indian patients with suspected abdominal tuberculosis revealed findings that included lymphadenopathy, organomegaly, peritoneal nodules, bowel wall thickening, mesenteric thickening, and ascites (21). Further research is required to determine whether ultrasound changes management of patients with ascites and helps to improve early diagnosis of abdominal TB and HIV-related complications.

Emergent ultrasound of trauma patients has been studied extensively in the United States, and additional research from South Africa supports the use of the FAST (focused assessment with sonography in trauma) exam on both blunt and penetrating trauma victims in resource-poor settings. In one study from a large trauma center in South Africa, sensitivity (72%) and specificity (100%) of FAST in this setting was similar to studies in western settings (22). This research suggests the FAST exam can be useful in determining which patients require emergent therapy for hemoperitoneum, and is especially important in settings with limited capacity for computed tomography (CT) to guide appropriate transfer for operative care.

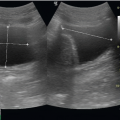

PEDIATRIC CONSIDERATIONS Ultrasound is emerging as a useful tool to assess degree of dehydration in children using measurements of the inferior vena cava (IVC) both in the United States and in sub-Saharan Africa (23,24). Death due to diarrhea-related volume depletion is a leading cause of death in children under 5 years of age worldwide (25), and a commonly encountered epidemic in human disasters. Accurate assessment of which children are significantly dehydrated and require hospitalization can aid in efficient resource utilization and guide rapid resuscitation. Bedside ultrasound of the Aorta:IVC ratio in children presenting with diarrhea in a Rwandan pilot study suggests that an Aorta:IVC ratio of >1.22 has a sensitivity of 93% (95% CI = 81% to 100%) to detect significant dehydration. This ultrasound assessment outperformed commonly used clinical scales for detection of dehydration, and requires further study.

PEDIATRIC CONSIDERATIONS Ultrasound is emerging as a useful tool to assess degree of dehydration in children using measurements of the inferior vena cava (IVC) both in the United States and in sub-Saharan Africa (23,24). Death due to diarrhea-related volume depletion is a leading cause of death in children under 5 years of age worldwide (25), and a commonly encountered epidemic in human disasters. Accurate assessment of which children are significantly dehydrated and require hospitalization can aid in efficient resource utilization and guide rapid resuscitation. Bedside ultrasound of the Aorta:IVC ratio in children presenting with diarrhea in a Rwandan pilot study suggests that an Aorta:IVC ratio of >1.22 has a sensitivity of 93% (95% CI = 81% to 100%) to detect significant dehydration. This ultrasound assessment outperformed commonly used clinical scales for detection of dehydration, and requires further study.

Editor’s note: The reader is cautioned that some studies report Aorta:IVC ratios; others report IVC:Aorta ratio. See also Chapter 26 (General Pediatric Problems) and Chapter 6 (IVC).

New uses for bedside ultrasound continue to emerge, and future research should focus on the utility of ultrasound for specific disease conditions, ideal training models for varying levels of proficiency, cost-effectiveness and long-term sustainability of ultrasound equipment and programs, and remote quality assurance and image management solutions. In addition, there is a need to create a uniform, standardized curriculum and international process of certification to ensure safe and high-quality ultrasound services worldwide.

PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION

Creating a sustainable ultrasound program in a low-resource setting requires much more than ultrasound equipment and good will. Many of the same components for success that are required to start an ultrasound program in a western ED are necessary in low-resource settings, with a few unique issues to ponder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree