John Reidy, Nigel Hacking and Bruce McLucas (eds.)Medical RadiologyRadiological Interventions in Obstetrics and Gynaecology201410.1007/174_2014_974

© Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014

Embolization in Pelvic Congestion Syndrome

(1)

Department of Radiology, UBC Hospital, 2211 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC, V6T 2B5, Canada

Abstract

Pelvic congestion syndrome remains a poorly understood entity whose existence, let alone appropriate methods of investigation and treatment, are still under legitimate question. It is important that any endovascular therapist contemplating ovarian vein embolization works closely with a gynecologist, not only to ensure that other causes of pelvic pain are excluded, but to share in the considerable post procedure needs of these patients. Pelvic congestion syndrome is increasingly being diagnosed both clinically and by imaging in patients with pelvic pain. Referral patterns are changing to include women being screened for lower extremity venous insufficiency. Although there is a striking consistency to the clinical improvement achieved by ovarian vein embolization by multiple authors, it is necessary that any physician undertaking this procedure convey the controversial nature of the syndrome to the patient. Improvement in pain symptoms should be expected in 80–90 % of patients with significant improvement in 60 %. Treatment appears durable at 5-year follow-up. There remains considerable variation in the endovascular approach, and the optimum approach remains to be proven.

1 Introduction

Embolization of the gonadal vein is one of the simplest procedures in endovascular medicine. Conversely, in clinical medicine, management of chronic pelvic pain is among the most difficult tasks. This is due to the difficulties with diagnosis and treatment detailed in the prior chapter. It is critical to reiterate that although varicosities in the pelvis secondary to ovarian vein reflux are a recognized cause of chronic pelvic pain (Cheong and Stones 2006), they are frequently seen incidentally on imaging studies in asymptomatic women. Without associated symptoms, dilated pelvic veins are not abnormal. As is the case with symptomatic male varicoceles (a well accepted clinical entity), it is not clear why some patients with gonadal venous reflux have pain when the majority don’t. Further complicating the situation, it is common for pelvic venous ectasia to develop after pregnancy (Hodgkinson 1953). However in “physiologic” venous ectasia blood flow is typically antegrade and there may not be sluggish flow or bulbous varicose venous dilation.

2 Clinical Presentation

There are four ways pelvic varicosities may come to the attention of a physician.

i.

Pelvic Congestion Syndrome. The features of the syndrome have been described in the previous chapter.

ii.

Labial or lower extremity varicose veins. For both surgical and endovascular treatments of venous reflux, the basic principle is to treat the highest point of reflux first. Vulvoperineal varicosities can be found in 4–8.6 % of patients with lower extremity venous insufficiency and may accompany ovarian vein insufficiency (Jung et al. 2009). Labial and perineal varicosities, lower extremity varicosities in unusual distributions, or lower extremity varicosities which recur after appropriate treatment can signal the presence of ovarian vein reflux. With increased patient demand and greater breadth of available therapies for varicose veins, this has become an increasingly frequent indication for investigation and treatment.

iii.

Acute ovarian vein thrombosis. This is an uncommon cause of acute abdominal or pelvic pain (Harris et al. 2012).

iv.

Incidental finding on cross-sectional imaging. On CT-dilated ovarian, veins can be seen in up to 63 % of parous women without symptoms of pelvic congestion and in 10 % of nonparous women (Rozenblit et al. 2001).

3 Preprocedure Workup

All patients with chronic pelvic pain should have the benefit of clinical evaluation by, and shared peri-procedural care with a clinician with expertise in chronic pelvic pain. Pelvic varices can be demonstrated by multiple imaging modalities, however, the author’s routine is to ensure the patient has had laparoscopy and pelvic ultrasound or MRI prior to pelvic venography. This is to exclude other disorders which might cause pelvic pain, not to make the diagnosis of pelvic congestion.

If the patient suffers from lower extremity varicosities, the workup before pelvic venography includes a detailed clinical assessment by a specialist physician expert in venous disease and a lower extremity duplex ultrasound assessment for venous reflux. Laparoscopy is not necessary in these patients unless there is suspicion of pelvic pathology.

3.1 Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is the most effective means of diagnosing other causes of chronic pelvic pain and virtually all women with chronic pelvic pain should undergo this procedure. In particular, minimal lesion endometriosis, the most common cause of chronic pelvic pain will not be detected by ultrasound and may only be detected by an expert laparoscopist. Dilated veins may not be visible because of their retroperitoneal location, the increased intra-abdominal pressure with peritoneal insufflation, and increased venous drainage with Trendelenberg positioning that are part of laparoscopic examination. Thus, a negative laparoscopy in a woman with chronic pelvic pain does not exclude the diagnosis of pelvic congestion.

3.2 Cross-Sectional Imaging

Although imaging can demonstrate pelvic varicose veins, direct visualization of tortuous and dilated ovarian veins with venography is still felt to be the gold standard for accurate diagnosis of pelvic congestion. The author does not view a normal noninvasive imaging study as a contraindication to ovarian venography when there are symptoms which might be due to pelvic congestion.

3.2.1 Ultrasound

Ovarian and pelvic varices can be seen as multiple dilated tubular structures with venous doppler signal around the uterus and ovary on both transabdominal or transvaginal US with color Doppler. Sonographic diagnostic criteria for pelvic congestion have been published (Kuligowska et al. 2005). These include: (a) tortuous pelvic veins with a diameter greater than 4 mm (b) slow blood flow (about 3 cm/s), and (c) a dilated arcuate vein in the myometrium that communicates between bilateral pelvic varicose veins. The author prefers to rely on abnormal accentuation of blood flow with Valsalva maneuver rather than utilizing strict size criteria. Veins can vary considerably with body position, nervousness or hydration, or may be dilated from physiologic ectasia from prior pregnancies.

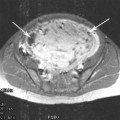

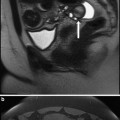

3.2.2 CT and MRI

On CT and MRI pelvic varices are seen as dilated tortuous paraovarian or parauterine tubular structures, frequently extending to the broad ligament and pelvic sidewall or paravaginal venous plexus (Coakley et al. 1999). On T1-weighted MR images, pelvic varices have no signal intensity because of flow-void artifact; on gradient-echo MR images the varices have high signal intensity. After the intravenous administration of gadolinium, T1 gradient-echo sequences demonstrate blood flow in pelvic varices with high signal intensity. On T2-weighted MR images they usually appear as an area of low signal intensity; however, possibly because of the relatively slow flow through the vessels, hyperintensity or mixed signal intensity may also be seen.

4 Ovarian Venography and Embolization

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree