Acute diverticulitis

Acute appendicitis

Primary epiploic appendagitis

Clinical settings and risk factors

Chronic low-fiber diet, physical inactivity, obesity, smoking, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Obesity, hernia, and unaccustomed exercise

Symptoms and signs

Diffuse lower abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, fever

Periumbilical pain migrating to the right lower quadrant area, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, fever

Localized pain in the lateral lower quadrant area

Physical and laboratory findings

Leukocytosis, rebound tenderness

Leukocytosis, rebound tenderness, guarding or rigidity

Usually – normal

Age

Older adults (>50 years of age)

All ages (peak, 10 years of age)

Younger adults (most commonly in 30–40 years of age)

Table 17.2

Differential diagnosis of inflammatory and infectious disease of the colon based on clinical findings

Ulcerative colitis | Tuberculous colitis | CMV colitis | PMC | Bacterial colitis | Ischemic colitis | Radiation colitis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clinical settings and risk factors | White, Jewish, developed countries, family history, and nonsmoker | Patients from endemic areas or immunocompromised patients | Immunocompromised patients | Recent antibiotic therapy or chemotherapy | Occlusive: thromboembolism, trauma, surgery, diabetes, vasculitis, tumor | Radiation therapy | |

Nonocclusive: shock, cardiac failure, drugs, colonic obstruction or overdistention | |||||||

Symptoms and signs | Persistent diarrhea, tenesmus, rectal bleeding, often a/w weight loss, fever, and arthralgia | Chronic symptoms including diarrhea, fever, night sweat, abdominal pain, anorexia, and weight loss | Diarrhea, weight loss, severe abdominal pain, hematochezia, fever | (Watery) diarrhea, colicky pain, fever | Abdominal pain, fever, diarrhea | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, abdominal distention, rectal bleeding | Diarrhea, tenesmus, cramping |

Physical and laboratory findings | pANCAs + | Leukocytosis | Frequently unremarkable | ||||

Age | 15–40 years of age | Adults | Elderly |

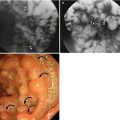

17.1 Diverticulitis

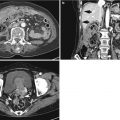

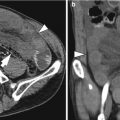

Most colonic diverticula are acquired herniations of the mucosa and submucosa (false diverticula) through the muscularis propria at weak points where vasa recta pass through the submucosa. Although the majority of colonic diverticula occur in the distal descending colon and sigmoid colon, they can occur anywhere throughout the colon. However, in Asian populations, right side involvement is more prominent (Almeida et al. 2009). Stasis or obstruction of diverticular neck by inspissated stool or food particles may cause inflammation, bacterial overgrowth, and localized ischemia, ultimately leading to microperforation of the diverticulum and pericolic inflammation which results in acute diverticulitis (Thoeni and Cello 2006). On CT, diverticula appear as small outpouchings of the colonic wall that contain air, contrast material, or fecal material. The involved colonic wall may show circumferential undulating thickening due to the thickening of circular muscle. Typical CT findings of diverticulitis include colonic diverticula with pericolic fat stranding or abscess and with adjacent colonic wall thickening that extends more than 5 cm. Other CT findings include engorged vessels supplying the affected segment, fluid in the mesenteric root, free intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal air, fistulae, and sinus tracts (Thoeni and Cello 2006; Almeida et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2005). On US, inflamed diverticula are shown as hypoechoic or hyperechoic outpouching of the colonic wall with focal disruption of the normal layer continuity and accompany increased peridiverticular fat echogenicity and segmental colonic wall thickening (Pradel et al. 1997). The most important differential diagnosis is colon cancer, especially in sigmoid diverticulitis with significant muscular thickening. CT features that indicate diverticulitis are inflamed diverticula (enhancement of thickened diverticular wall surrounded by the area of peridiverticular inflammation), layered enhancement pattern, long-segment involvement (>10 cm), and inflammatory changes in pericolic area and mesentery (Thoeni and Cello 2006; Jang et al. 2000). However, perforated colon cancer can be associated with inflammation or abscess, thus mimicking diverticulitis. When CT findings are equivocal, barium enema or colonoscopy should be performed to exclude colon cancer after treatment of diverticulitis. On barium enema, partial colonic obstruction, gradual zone of transition, preservation of mucosal folds, and associated diverticula indicate diverticulitis (Laufer 2008).

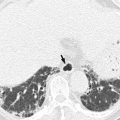

17.2 Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis occurs when the appendiceal lumen is obstructed from any cause such as fecalith, lymphoid hyperplasia, foreign bodies, parasites, and tumors. Obstruction leads to luminal distention, tissue ischemia, bacterial overgrowth, transmural inflammation, and finally perforation. CT findings of non-perforated acute appendicitis include outer appendiceal diameter greater than 6 mm, symmetric appendiceal wall thickening greater than 2 mm, appendiceal wall hyperenhancement, mural stratification, cecal apical thickening, and inflammatory changes in the periappendiceal area and contiguous structures including the terminal ileum. There is a wide variation in the diameter of the appendix in normal patients (up to 1 cm). Therefore, when the appendix measures between 6 and 10 mm on CT, other CT findings as well as clinical findings should be considered for the diagnosis. CT findings suggesting perforated appendicitis include a defect in enhancing appendiceal wall, periappendiceal abscess, extraluminal appendicolith, and extraluminal air (Birnbaum and Wilson 2000; Pinto Leite et al. 2005). US is recommended as an initial imaging study in children, thin young women, and pregnant women. A graded compression technique should be performed throughout the entire length of the appendix. US criteria for acute appendicitis are outer transverse appendiceal diameter greater than 6 mm, non-compressibility, circumferential color Doppler signal in the wall, increased periappendiceal fat echogenicity, intraluminal fluid, and the absence of gas in the appendix. When ischemic or gangrenous change prior to perforation occurs, a loss of wall layers and decreased or no color Doppler signal can be seen. Although CT demonstrates higher sensitivity, accuracy, and negative predictive value for the diagnosis than US, CT and US complement each other when the results of initial examination are equivocal or suboptimal (Birnbaum and Wilson 2000). MRI can be a good alternative to CT in patients with a risk of contrast-induced nephropathy or during pregnancy. MRI features of acute appendicitis include appendiceal diameter greater than 7 mm, appendiceal wall thickening greater than 2 mm, hyperintense luminal contents, and hyperintense periappendiceal fat stranding and fluid on T2WI (Spalluto et al. 2012).

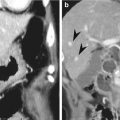

17.3 Epiploic Appendagitis

Primary epiploic appendagitis is a rare, self-limited inflammation of epiploic appendages (also known as appendices epiploicae) that are peritoneal pouches arising from the serosal surface of the colon, to which they are attached by a vascular stalk. Torsion or spontaneous venous thrombosis of the epiploic appendages with resultant infarction and inflammation is a cause of primary epiploic appendagitis. The most common site is the area adjacent to the sigmoid colon followed by the descending colon and right hemicolon (Singh et al. 2005). A unique CT finding is an oval fatty lesion less than 5 cm in diameter surrounded by inflammatory changes that abuts the anterior colonic wall (Almeida et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2005). Associated colonic wall thickening is usually absent. The presence of a hyperattenuating rim representing the thickened visceral peritoneum surrounding an inflamed epiploic appendix is a diagnostic finding. A central hyperattenuating area corresponding to central thrombosed vessels, hemorrhage, or fibrosis is sometimes seen. Omental infarction may have a similar CT appearance, but it appears as a larger, cake-shaped lesion centered in the omentum and lacks the hyperattenuating rim and central hyperattenuating area (Almeida et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2005). The characteristic US finding is a non-compressible hyperechoic mass with hypoechoic halo at the site of maximal tenderness, adjacent to the colon, with no central blood flow depicted on color Doppler US images (Almeida et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2005). The absence of color Doppler signal and lengthy colonic wall thickening are useful findings to differentiate primary epiploic appendagitis from secondary epiploic appendagitis due to acute diverticulitis (Singh et al. 2005).

17.4 Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is one of the main subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease that primarily affects the mucosa. It begins in the rectum with variable degrees of continuous, circumferential, and proximal extension throughout the colon. In an acute phase, mucosal granularity attributable to mucosal edema, hyperemia, and abnormal mucin production is the earliest radiographic finding on double-contrast barium enema (DCBE). As inflammation worsens, continuous and symmetric wall thickening often with water halo sign can be seen on CT. Ulcerations through the mucosa and submucosa with lateral spread in the submucosal layer results in characteristic collar button ulcers on DCBE. Extensive ulcerations leave islands of mucosal remnants, creating inflammatory pseudopolyposis which may be seen in a well-distended colon on CT as well as on DCBE. In chronic phase, mural thickening with fat halo sign, luminal narrowing, and widening of presacral space are commonly seen on CT due to the hypertrophy of the muscularis mucosa and fat deposition in the submucosa and perirectal area. On DCBE, the involved colon shows a narrowed, ahaustral, and shortened appearance often with postinflammatory pseudopolyposis (abnormal proliferation of inflamed mucosa) (Gore et al. 1996; Lichtenstein 1987). Toxic megacolon, a potentially fatal complication, is characterized by both nonobstructive colonic dilatation of at least 6 cm and evidence of systemic toxicity (Sheth and LaMont 1998). Typical findings are marked colonic dilatation with an ahaustral pattern often associated with thin wall and ill-defined, nodular inner margin on plain radiograph and CT (Thoeni and Cello 2006). Pancolitis or chronic ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased colorectal cancer risk. These cancers with flat or infiltrating type are difficult to diagnose early by DCBE and even by colonoscopy. On CT, features of asymmetric marked mural thickening and loss of mural stratification suggest associated malignancy (Thoeni and Cello 2006; Gore et al. 1996).

17.5 Infectious Colitis

17.5.1 Tuberculous Colitis

Due to the abundant lymphoid tissue and relative stasis, tuberculous colitis almost always involves the ileocecal valve and adjacent cecum and ileum (up to 90 % of cases) by ingesting contaminated milk products or in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis by swallowing tracheobronchial secretions (Thoeni and Cello 2006; Jadvar et al. 1997). On DCBE, transverse ulcerations following the orientation of colonic lymphoid follicles, thickening and wide gaping of ileocecal valve with narrowed terminal ileum (Fleischner sign), and a conically shrunken cecum without distinction from the terminal ileum (Stierlin’s sign) are characteristic findings. Other findings include symmetric annular stenosis, shortening, retraction, and pouch formation in advanced cases (Jadvar et al. 1997). Characteristic CT findings include asymmetric thickening of the ileocecal valve and medial cecum, exophytic extension engulfing the terminal ileum, and enlarged mesenteric lymphadenopathy with peripheral enhancement and central low attenuation (Jadvar et al. 1997). Pericolic fat stranding is absent or minimal. Tuberculous colitis mimics many of the features seen in Crohn’s disease. However, ulcers tend to be larger and oval, and bowel wall thickening may be more prominent without mural stratification than in Crohn’s disease. Fistulae and sinus tracts are less common than in Crohn’s disease (Thoeni and Cello 2006; Jadvar et al. 1997).

17.5.2 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Colitis

CMV colitis usually occurs in immunocompromised patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or who have received immunosuppressive therapy or organ transplantation. CMV-induced occlusive vasculitis with ischemic injury leads to ulceration in the gastrointestinal tract (Balthazar and Martino 1996). CMV colitis may involve the cecum sometimes with distal ileal involvement. It may be segmentally distributed or may present as pancolitis. Common CT features include marked mural thickening (8–33 mm, mean 15 mm), mural edema, mucosal ulceration, pericolic fat stranding, and ascites. Lymphadenopathy is not a predominant feature. In severe CMV colitis, hemorrhage within the colonic wall and colon perforation can develop (Murray et al. 1995). The diagnosis can be made by detection of large cells containing intranuclear and often intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies on the colonoscopic biopsy specimens (Balthazar and Martino 1996).

17.5.3 Pseudomembranous Colitis

Pseudomembranous colitis is a potentially life-threatening acute infectious colitis caused by toxins produced by an unopposed proliferation of Clostridium difficile bacteria in the colon. It usually occurs as a complication of antibiotic therapy. At colonoscopy, pseudomembranous colitis is characterized by multiple adherent yellow plaques on the ulcerated mucosa representing pseudomembranes (Kawamoto et al. 1999). As the disease progresses, reactive edema develops leading to marked transmural thickening. CT may reveal pancolitis or segmental colitis. The rectum and sigmoid colon are typically involved, but some may have disease confined to the right colon. Common CT findings include marked low-attenuation mural thickening, accordion sign, target sign, pericolic fat stranding, and ascites. The accordion sign (alternating thickened haustral folds separated by transverse mucosal ridges filled with oral contrast material) was reported to be a specific sign of severe pseudomembranous colitis, but other conditions may cause this sign at CT, such as edema related to cirrhosis, ischemia, lupus, and some infectious colitis including CMV colitis (Macari et al. 1999). Relative paucity of pericolic fat stranding in combination with marked colonic wall thickening and the presence of ascites helps differentiate pseudomembranous colitis from other colitis including inflammatory bowel disease (Kawamoto et al. 1999).

17.5.4 Bacterial Colitis

This type of infectious colitis is usually confirmed clinically on the basis of stool analysis and/or colonoscopic findings with biopsy results. They share the CT features of mural thickening, pericolic fat stranding, and ascites. However, if CT shows involvement limited to the right colon with or without terminal ileum in clinical suspicion of infectious colitis, Yersinia or Salmonella may be inferred as a causative organism, whereas left colon involvement is typical for Campylobacter or Shigella infections (Thoeni and Cello 2006).

17.6 Ischemic Colitis

Ischemic colitis represents partial mural ischemia mainly affecting the mucosa and submucosa that is usually seen in elderly patients. With disease progression, necrosis of the muscle layer can lead to the fibrotic stricture or transmural infarction. It is caused by mesenteric vascular occlusion, low flow or vasospasm, as well as strangulated colonic obstruction or overdistention. Watershed segments such as the splenic flexure and the rectosigmoid colon are commonly affected in nonocclusive ischemia. However, any part of the colon can be involved if small vessel disease and/or reperfusion injury occurs. Intramural necrosis is always followed by intramural edema and/or hemorrhage often with superinfection (Wiesner et al. 2003). Therefore, common CT findings include segmental mural thickening, water halo sign, pericolic fat stranding, and ascites. The colonic wall is thin and unenhanced, associated with luminal dilatation when the involved colon becomes infarcted due to total vascular occlusion without reperfusion (Thoeni and Cello 2006; Wiesner et al. 2003). Pneumatosis coli and portomesenteric venous gas are infrequent but ominous findings indicating transmural infarction. The diagnosis is dependent on the history and clinical findings, and colonoscopy is needed for definitive diagnosis (Thoeni and Cello 2006).

17.7 Radiation Colitis

Radiation colitis is characteristically localized to the radiation port, which is commonly in the pelvis for treatment of genitourinary tract neoplasms. The sigmoid colon and rectum are most commonly affected. In acute stage, radiation damages the actively proliferating mucosa. Wall thickening with edema and inflammatory standing can be seen. Chronic injury is due to radiation-induced endarteritis. This chronic ischemia leads to fibrosis of the bowel wall, often manifesting as stricture, fistula, and sinus tract. Increased mural and perirectal fat and thickening of perirectal fibrous tissue can be seen in the chronic stage. The CT appearance is nonspecific, but the clinical history will help suggest the diagnosis (Capps et al. 1997).

17.8 Extracolonic Diseases Involving the Colon: Actinomycosis and Endometriosis

The colonic wall can be involved by adjacent extrinsic diseases. Among these, actinomycosis is a chronic infection characterized by formation of well-enhancing abscesses or masses rich in granulation and fibrous tissues and extensive infiltration across the adjacent tissue planes. It is caused by Actinomyces israelii and commonly associated with bowel perforation, surgery, trauma, and intrauterine device. The sigmoid colon is the most common segment of the colon involved (Lee et al. 2001). Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterus. The rectosigmoid colon is the most common segment of intestinal endometriosis. Implants are usually attached to serosal surface but can eventually erode through the subserosal layers and cause marked thickening and fibrosis of the muscularis propria (Woodward et al. 2001).

Summary

1.

Specific CT features help distinguish various types of colitis and assist patient’s management although the final diagnosis of colitis is often based on clinical, laboratory, and colonoscopic findings with biopsy.

2.

Typical CT findings of diverticulitis include colonic diverticula with pericolic fat stranding or abscess and with adjacent colonic wall thickening that extends more than 5 cm.

3.

CT features that indicate diverticulitis rather than colon cancer are inflamed diverticula, layered enhancement pattern, long-segment involvement (>10 cm), pericolic fat stranding, engorged mesenteric vessels, and fluid in the mesenteric root.

4.

When the appendix is equivocally distended (between 6 and 10 mm) on CT, other CT findings as well as clinical findings should be considered to diagnose acute appendicitis due to a wide variation in the diameter of the appendix in normal patients (up to 1 cm).

5.

US is recommended as an initial imaging study in children, thin young women, and pregnant women for diagnosing appendicitis, while MRI can be a good alternative to CT in patients with risk of contrast nephropathy or during pregnancy.

6.

Less than 5 cm oval fatty lesion surrounded by inflammatory changes that abuts the anterior colonic wall is a diagnostic CT feature of primary epiploic appendagitis.

7.

In acute phase of ulcerative colitis, mucosal granularity, collar button ulcers, and inflammatory pseudopolyposis are characteristic findings on DCBE. On CT, continuous and symmetric wall thickening often with water halo sign involves the rectum with variable degrees of proximal extension throughout the colon.

8.

In chronic phase of ulcerative colitis, mural thickening with fat halo sign, luminal narrowing, and widening of presacral space are common on CT. On DCBE, the involved colon shows a narrowed, ahaustral, and shortened appearance often with postinflammatory polyposis.

9.

A conically shrunken cecum without distinction from the terminal ileum (Stierlin’s sign) is distinguishing DCBE feature of tuberculous colitis from Crohn’s disease in the ileocecal area.

10.

Asymmetric more prominent wall thickening, absent mural stratification, and enlarged mesenteric lymphadenopathy with central low attenuation are distinguishing CT features of tuberculous colitis from Crohn’s disease in the ileocecal area.

11.

Although CT findings are not specific, CMV colitis should be suggested when CT shows marked colonic wall thickening associated with mural ulceration in the immunocompromised patients.

12.

Marked low-attenuation mural thickening accounting for the accordion sign, relative paucity of pericolic fat stranding, and the presence of ascites may suggest the diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis in patients with history of recent antibiotic therapy on CT.

13.

If CT shows involvement limited to the right colon with or without terminal ileum in clinical suspicion of infectious colitis, Yersinia or Salmonella may be inferred as a causative organism, whereas left colon involvement is typical for Campylobacter or Shigella infections.

14.

Segmental mural thickening involving the left side colon may suggest the diagnosis of ischemic colitis in elderly patients with history and clinical findings suspicious of ischemic colitis.

15.

When the clinical history of radiation therapy is present and CT findings are localized to the radiation port, radiation colitis will be suggested.

16.

Actinomyocosis should be considered when CT shows regional mass with extensive infiltration across the tissue planes adjacent to the thickened colon wall, especially in patients with abdominal pain, fever, leukocytosis, or long-term use of intrauterine device.

17.

Extrinsic mass effect in association with spiculation of the colon wall and intact mucosa is a typical DCBE finding of colonic endometriosis. On MR, enhancing solid nodules that are hypointense on T2WI and are contiguous to or penetrating the thickened colonic wall are highly suggestive of colonic endometriosis (Tables17.3 and 17.4).

Table 17.3

Differential diagnosis of inflammatory and infectious disease of the colon based on MDCT findings

Acute diverticulitis | Acute appendicitis | Primary epiploic appendagitis | |

|---|---|---|---|

Location and extent | SC, DC in Western countries, right colon in Asian countries | Appendix, posteromedial cecum | SC > DC > right colon |

Mural thickening degree (mean maximal diameter) | Mild, usually <5 mm, can be up to 2–3 cm in significant muscular thickening of SC | Appendix: ≥ 3 mm | Most often –, may have mild reactive thickening |

Mural thickening appearance | Symmetric or more pronounced on the side of inflamed diverticula, long segment (>5 cm), smooth, arrowhead sign (27 %) | Appendix: symmetric, | Asymmetric |

Cecum: focal apical thickening, arrowhead sign (30 %), cecal bar sign (10–15 %) | |||

Target sign | + In right colon | Often + | – |

Small bowel involvement | Rare, coloenteric fistula | Often focal terminal ileal thickening | – |

Pericolic fat stranding | +++ Can be disproportionately more severe than degree of colonic wall thickening | ||

Ascites | Often + | Often + | – |

Lymphadenopathy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|