Figure 30.1

Suggested flowchart for the use of imaging techniques in patients with perianal fistulas. Patients with suspected perianal fistulas may be stratified based on the presence or absence of Crohn’s disease. Those with a suspected fistula of cryptoglandular origin may benefit from perianal ultrasound as the initial imaging examination. In patients in whom the clinical diagnosis of simple fistula has been confirmed, the diagnostic work-up may be stopped, whilst in those with complex fistulas the recommended approach consists of further investigations by means of transanal ultrasound (with or without peroxide fistulography), MRI, or both before exam under anesthesia and/or surgical treatment

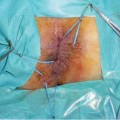

The treatment of perianal fistulas depends mainly on the nature of the lesion, whether cryptogenetic or Crohn’s related, and on its classification. The latter takes into account several aspects, such as the anatomical site of the internal opening, the course of the fistula in relation to the anal sphincters, and in particular the presence of extensions, branches, and perianal abscesses.

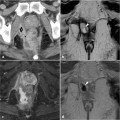

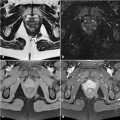

The main diagnostic tools currently used to classify perianal fistulas are transanal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), exam under anesthesia (EUA), and trans-perineal ultrasound. However, sometimes these procedures are contraindicated or not available; moreover, their accuracy is less than 100%. A recent meta-analysis assessed the accuracy of transanal ultrasound and MRI for detecting perianal fistula, showing that the sensitivity of these methods was comparable and high (87% for each one) and that the specificity of MRI was higher than that of transanal ultrasound (63% vs. 43%). However, both specificity values are considered diagnostically poor, especially considering the heterogeneity between studies of the two procedures [2].

Missed lesions and false-positive results are also possible with simple surgical digital examination and even with EUA. While the former results in the incorrect assessment of primary tracts and abscesses in 40–60% of cases [3], the latter, even when performed by experts, may misclassify up to 10% of perianal fistulas [4]. These considerations should be taken into account in the planning of medical and surgical treatment, given that an inaccurate diagnosis may lead to disease progression, with an increased risk of recurrence, on the one hand, as well as to inappropriate surgery, with irreversible functional consequences on the other. Consequently, the correct use of imaging procedures, their appropriate combination, and the cooperation of radiologists, surgeons, and gastroenterologists are crucial for the successful treatment of perianal fistulas and the prevention of their recurrence.

30.2 Perianal Fistulas Classifications

To correctly plan treatment, the classification of perianal fistulas should be clearly interpretable by the involved surgeons and gastroenterologists. The most commonly and widely used classification system, that of Parks, dates from 1976 [5]. The Parks criteria rely on an anatomically precise system in which the external anal sphincter is the central reference point. Five types of perianal fistulas are therefore described: (a) intersphincteric fistula, characterized by a primary tract that courses in the intersphincteric space without penetrating (<30%) the external sphincter; (b) trans-sphincteric fistula, which traverses the external sphincter and passes into the ischioanal fossa, below the level of the puborectalis muscle; (c) suprasphincteric fistula, which travels within the intersphincteric plane superior to the puborectalis before penetrating the levator musculature to course within the ischiorectal and ischioanal fossae; (d) extrasphincteric fistula, which courses within the ischioanal fossa and penetrates the levator musculature without traversing either the internal or the external sphincters, instead opening directly into the rectum; and (e) superficial fistula.

However, these criteria have their limitations because they do not consider relevant information on perianal disease, such as the presence or absence of macroscopic rectal inflammation, co-existing perianal abscesses, or fistulous connection to other structures such as the bladder, vagina, or anal strictures, which may affect the choice of treatment as well as patient outcome. To overcome this deficit, an American Gastroenterological Association technical review panel on perianal Crohn’s disease developed a simplified but more clinically relevant approach to classifying fistulas [6], describing them as either simple or complex. A simple fistula is a superficial, intersphincteric, or low trans-sphincteric fistula with only a single opening and not associated with an abscess and/or not connected to an adjacent structure such as the vagina or bladder. A complex fistula involves more of the anal sphincter (i.e., high trans-sphincteric, extrasphincteric or suprasphincteric), has multiple openings, horseshoeing (crossing the midline either anteriorly or posteriorly), an association with a perianal abscess, and/or a connection to an adjacent structure such as the vagina or bladder [6]

Patients with complex fistulas are at increased risk for incontinence following aggressive surgical intervention. They also have a reduced rate of fistula healing and greater likelihood of recurrence.

Other perianal disease classification systems and scores, such as the Cardiff classification and perianal disease activity index (PDAI), are rather complex; accordingly, their acceptance and use in clinical practice have been limited [7, 8].

Irrespective of the system employed to classify perianal fistula, an accurate description of the fistulous tracts is of utmost importance. The presence of branching or horseshoeing (crossing the midline anteriorly or posteriorly) and its location (intersphincteric, infralevator, supralevator) must be noted since the presence of either one may change the surgical management [9]

30.3 Comparison of Diagnostic Imaging Techniques in Perianal Fistulas

The choice of the imaging technique for the detection and characterization of perianal disease is currently based upon several factors: local availability and expertise, cost of the procedure, the particular features of the perianal disease, and the age of the patient as well as the disease duration. In some instances, the use of at least two modalities may be necessary; this is often the case in patients with recurrent or complicated perianal disease [10].

Ideally, patients without well known intestinal inflammatory disease in whom fistula-in-ano is suspected should, after the initial clinical history and physical and digital anorectal examinations, undergo transperineal ultrasound in order to confirm the diagnosis. This method is widely and promptly available, inexpensive, and according to the literature data sufficiently accurate both in confirming a perianal fistula and in classifying its type. Complex perianal fistula initially suspected at digital examination or assessed by preliminary trans-perineal ultrasound prior to EUA or surgical treatment should be assessed by transanal ultrasound, MRI, or both, according to the disease complexity and the surgeon’s discretion (Fig. 30.1)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree