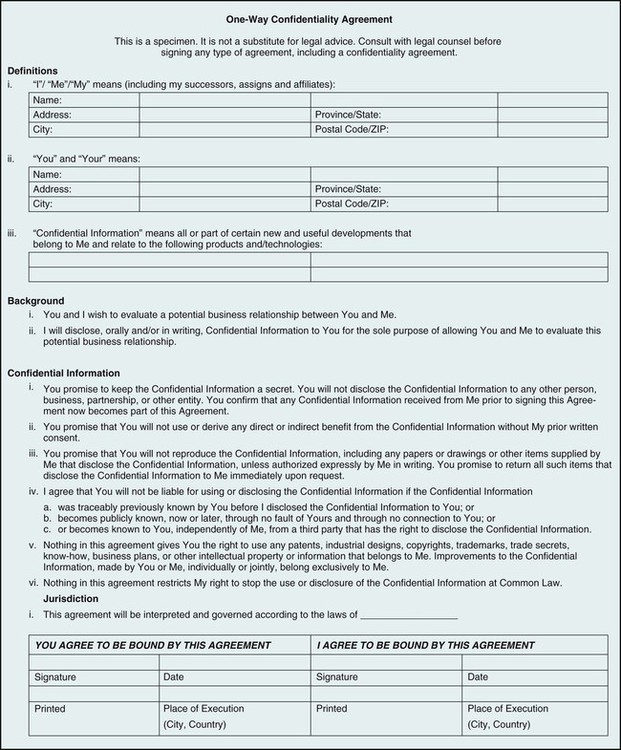

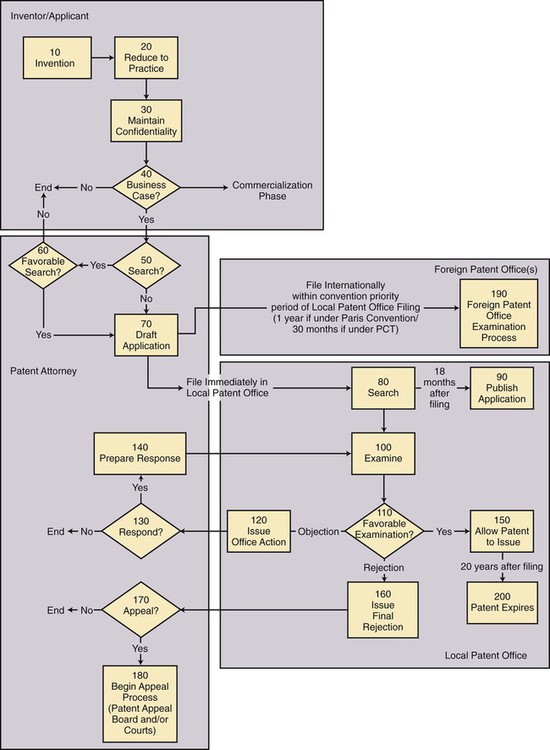

Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, said with respect to the value of intellectual property, “The economic product of the United States has become predominantly conceptual.”1 It has been estimated that as much as 75% of the value of publicly traded companies in the United States comes from intangible assets, up from 40% in the early 1980s.1 In the United States alone, technology licensing revenue accounts for an estimated $45 billion annually; worldwide, the rapidly growing figure is now around $100 billion,1 a significant portion of which can be attributed to pharmaceutical and medical-related patents. Conversely, savvy inventors who use the patent system can reap enormous financial rewards from their inventions. As a rare though salient example, Dr. Gary K. Michelson conceived a number of spine surgery–related inventions and obtained patents for those inventions. On April 22, 2005, Medtronic Inc. paid $1.35 billion to settle a patent lawsuit2 brought by Dr. Michelson and acquire his patents. 1. Assume entity A possesses information known only to A, and thus such information will qualify as confidential information. 2. Assume that entity A and entity B have a relationship whereby B understands that information imparted by A to B must be kept confidential by B. 3. On the basis of these assumptions, if A imparts the confidential information to B, then B will have a legal obligation to keep the confidential information secret. 4. If B violates that legal obligation and imparts the confidential information to C, then A will have a right to sue B and seek damages for losses suffered as a result of B’s actions. Outside the employment context, the most common way to establish a confidential relationship is through a legal contract called a confidentiality agreement or nondisclosure agreement (NDA). As the name suggests, the contract will establish the confidential relationship between the parties and govern the terms of the transfer of information between the parties. Absent a patent, this is the best way for an inventor to protect his or her ideas. Furthermore, confidential information that is imparted without a confidentiality agreement will no longer be “confidential” and will therefore compromise the ability to secure a patent for any inventions within the confidential information. The confidentiality agreement is a simple cost-effective means to allow the inventor to share his or her ideas with others on a basis that makes clear that the information exchanged under the agreement belongs to the inventor and must be kept confidential. (See One-Way Confidentiality Agreement, Fig. e14-1.) In the United States and other countries with economic roots in the English legal system (e.g., England, Canada, Australia, New Zealand), patents exist as a carve-out to the historic general prohibition against monopolies.3 The carve-out is believed necessary to encourage innovation. In the United States, it is written in the Constitution: “Section 8. The Congress shall have power…To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” Patents and copyrights are close cousins, with patents protecting useful innovations and copyrights protecting artistic works. Of important note is that patents and copyrights are always time-limited monopolies—they cannot be indefinite. Figure e14-2 shows a flow chart exemplifying the patent process, from conception to issuance or final rejection of the patent. Boxes 10 to 40 reflect the steps taken by the inventor; Boxes 50 to 70, 130, 140, 170, and 180 reflect the steps taken by the patent attorney. The remaining boxes reflect the steps taken by local and foreign patent offices.

Intellectual Property Management

Confidential Information and Confidentiality Agreements

Patents

Patent Application Process

Intellectual Property Management