Interventional Gastrointestinal Radiology

Loren Ketai

L. Ketai: Department of Radiology, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131.

BLEEDING

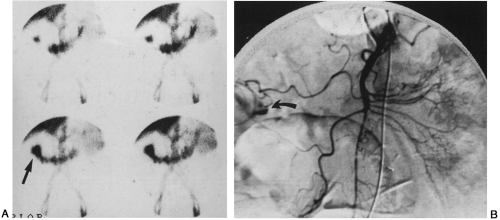

Endoscopy is the diagnostic examination most frequently used in the evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding. Nuclear medicine scans with labeled red blood cells are used to localize the site of cryptogenic bleeds and can detect blood loss rates as low as 0.1 ml/minute over a 10-minute period. Angiography is not as sensitive as nuclear medicine studies and requires flow rates of 0.5 ml/minute or faster (Fig. 15-1). Bleeding is characterized by localized extravascular puddling of contrast medium which persists after washout of the contrast agent from the vasculature. Both conventional films and digital subtraction images can be used, but the latter may be degraded by artifact from the peristaltic motion of the gut.

Angiography is most often used when subsequent transcatheter treatment with vasopressin or embolization is being considered.9,14,15,18 Transcatheter treatment can provide definitive therapy of some gastrointestinal bleeding, and in other cases it can temporarily halt acute blood loss, stabilizing the patient so that definitive surgical therapy can be performed. Intra-arterial administration of vasopressin may stop acute bleeding due to gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, colonic diverticuli, and other causes. Embolization, often with gelatin sponge (Gelfoam), may be effective in cases not responding to vasopressin, but it is controversial in the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries because of the risk of bowel infarction. Angiography is generally not used in the evaluation of venous bleeding, such as from esophageal varices, except to determine portal vein patency. It can not directly demonstrate the bleeding site, and therapy for varices depends on alleviation of portal hypertension rather than transcatheter treatment (see next section).

TREATMENT OF PORTAL HYPERTENSION

Treatment of portal hypertension is undertaken primarily to control and prevent variceal (esophageal, gastric, rectal) bleeding, which carries a mortality risk of more than 30%. Endoscopic sclerotherapy is frequently performed for esophageal varices, but despite an immediate success rate of 80% to 90%, there is a 50% incidence of rebleeding. Moreover, gastric varices are often inaccessible to this therapy.

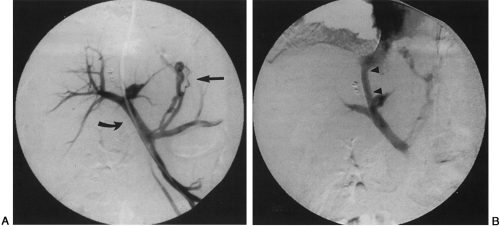

The mainstay of radiologic intervention for portal hypertension is the Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (TIPS) (Fig. 15-2).6,8 The goal of this procedure is to lower the portal venous pressure to less than 12 to 15 mm Hg. TIPS is performed by gaining access to a hepatic vein (usually the right) via an internal jugular vein. A long sheathed (Colapinto) needle is placed into the hepatic vein and passed though the liver parenchyma into the portal vein. This is the key step in the procedure. Although a variety of image guidance techniques have been proposed for puncture of the portal vein, operator experience is the most important determinate of success. After the portal vein has been entered, the tract is dilated and a metal stent is placed to maintain tract patency.

After successful TIPS placement, hepatic encephalopathy is the most frequent complication. The shunts should be monitored with Doppler ultrasound because of the high rate of TIPS stenosis or occlusion (more than 40%) during the first year after placement. These malfunctions are usually treatable by angioplasty or additional stenting, or both.

PERCUTANEOUS ABDOMINAL BIOPSY

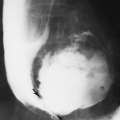

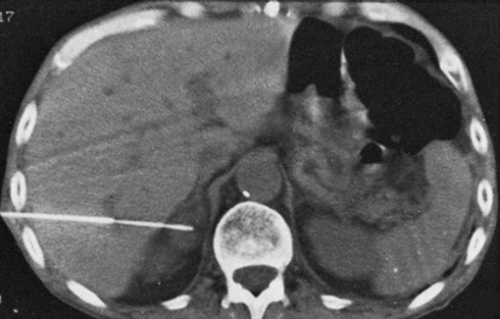

Although vascular interventions in the abdomen can be life-saving, nonvascular interventions are much more frequently performed.16 Of these interventions, percutaneous abdominal biopsy is probably the most common. Biopsies may be guided by ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 15-3). Although CT better identifies bowel and bony

structures, ultrasound provides real-time imaging which is advantageous if the biopsy path must be angled in more than one plane.4

structures, ultrasound provides real-time imaging which is advantageous if the biopsy path must be angled in more than one plane.4

FIG. 15-3. CT-guided biopsy of a right adrenal gland mass. A similar technique can be used for percutaneous biopsy of any nonvascular abdominal mass. |

Fine needles (20 to 22 gauge), larger cutting needles, and automated biopsy devices are all used to obtain tissue samples. Smaller-gauge needles should be considered in cases in which the risk of hemorrhage is high, as in biopsies of hepatomas and other vascular tumors. Larger needles and automated devices, which provide core tissue samples, produce a better diagnostic yield in biopsies of lymphoma and benign processes.

TREATMENT OF ENTERIC STRICTURES

Enteric strictures (most commonly esophageal) can be treated nonsurgically with either an endoscopic or a radiologic

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree