The Teeth, Jaws, and Salivary Glands

J. Shannon Swan

J. S. Swan: Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin Clinical Science Center, Madison, Wisconsin 53792-3252.

Roentgen examination of the teeth is used by the medical profession largely to determine the presence or absence of infection involving the teeth and jaws. Certain changes in the alveolus result from generalized disease, and examination of the teeth is also helpful in these conditions. Tumors arising on the alveolar ridge, tongue, or other intraoral sites may involve the bony alveolus. Roentgen examination is used to detect, plan therapy, and follow the progress of these tumors.

Specific techniques for dental radiography include intraoral dental radiographic study and the panoramic type of extraoral examinations. Three general intraoral methods of examination used: intraoral dental, bitewing, and occlusal. The standard intraoral films are placed in position and held there by the patient while the exposure is being made. These exposures should include the crowns and roots of all teeth. Bitewing films are used to examine the crowns of the teeth. These films have a central flap that is held between the teeth with the mouth closed. Each film then includes upper and lower dental crowns. The occlusal film is larger and is also employed as an intraoral film. It is used most widely in patients who are edentulous in a search for retained root fragments or local infection of the alveolus. It is also useful in the examination of small cysts or tumors of the alveolar ridge and jaw.

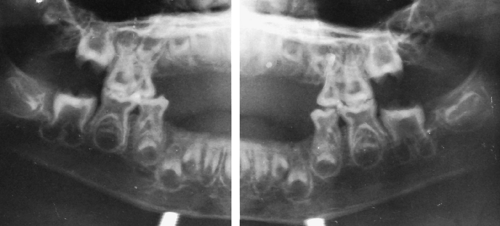

Panoramic devices save time and radiation exposure. They are used as a dental screening device and as a method of examining the alveolar ridges and adjacent portions of the maxilla as well as the mandible. A number of panoramic devices are available, with a variety of special features to suit the needs of physicians interested in the teeth and jaws as well as those of the oral surgeon and dentist (see Fig. 39-11). These devices rotate around a fixed head position during filming. A single exposure may be used to survey all of the teeth as well as the jaws. The lesser quality of panoramic films is appropriate for examination of the mandible and maxilla and as a screening examination of the teeth. The panoramic methods reduce radiation exposure considerably, from a dose of about 15 rad for a full-mouth dental survey with two bitewing exposures to about 3 rad for a panoramic exposure plus bitewings. Lead-lined cones are effective in reducing skin exposure in dental radiography. The mandible is examined by means of special views in frontal and lateral oblique projection in most institutions. The low Townes’ view is preferred in our institution to supplement a panoramic study. The temporomandibular joints (TMJs) also require special techniques and are examined with the mouth opened and closed. Films of the normal joint are usually obtained for comparison purposes. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are of considerable value in the examination of the TMJs, with MRI usually preferred for most circumstances. Arthrography of the TMJs is now used infrequently.

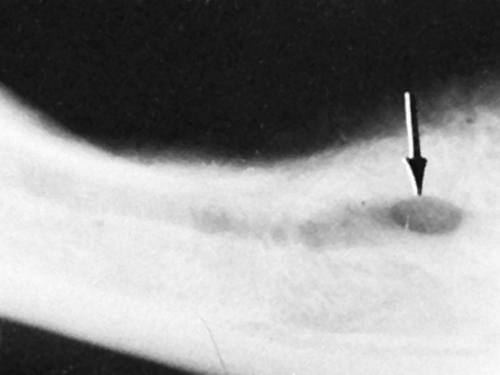

FIG. 39-5. Mental foramen. The arrow indicates the foramen. The mandibular canal extends posteriorly from the foramen in this edentulous mandibular alveolus. |

FIG. 39-6. Dental caries. Note the multiple radiolucent defects in the crowns of the teeth. These are very advanced lesions. |

THE NORMAL TEETH

The discussion of dental and jaw problems is necessarily limited in this text. Those interested in more detailed information should refer to texts such as Stafne’s Oral Radiographic Diagnosis, edited by Gibilisco,7 and Goaz and White’s Oral Radiology.9

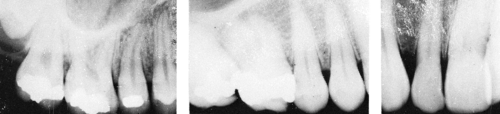

The teeth appear in two sets. The first are termed deciduous or temporary teeth. There are 20 deciduous teeth, 10 in each jaw, 5 in each quadrant. They are named from the midline as follows: central incisor, lateral incisor, cuspid, first molar, and second molar. In the adult jaw there are normally 32 teeth, 8 in each quadrant, named as follows from the midline: central incisor, lateral incisor, cuspid (canine), first bicuspid (premolar), second bicuspid (premolar), first molar, second molar, and third molar. Examples of these teeth are shown in Figs. 39-1, 39-2, 39-3, and 39-4.

Each tooth consists of a crown, which is covered by enamel, and a root. The junction between them is called the neck, cervix, or cementoenamel junction. The roots, which are covered with cementum, lie in sockets in the alveolar

process of the jaw and are attached by the periodontal ligament to the alveolar bone. Many variations in opacity are noted on dental radiographs. In decreasing order, they are (1) metal crowns and restorations, (2) enamel of the teeth, (3) dentin underlying the enamel, (4) cementum, (5) cortical bone, (6) cancellous bone, and (7) medullary spaces, canals, foramina, and soft tissues. The crown of the tooth is therefore slightly more dense than the root, and within each tooth is a narrow radiolucency termed the root (pulp) canal. Immediately surrounding each tooth is a radiolucent space representing the alveolar periosteum (periodontal membrane). Adjacent to this is a thin, dense structure composed of compact bone called the lamina dura (see Fig. 39-4).

process of the jaw and are attached by the periodontal ligament to the alveolar bone. Many variations in opacity are noted on dental radiographs. In decreasing order, they are (1) metal crowns and restorations, (2) enamel of the teeth, (3) dentin underlying the enamel, (4) cementum, (5) cortical bone, (6) cancellous bone, and (7) medullary spaces, canals, foramina, and soft tissues. The crown of the tooth is therefore slightly more dense than the root, and within each tooth is a narrow radiolucency termed the root (pulp) canal. Immediately surrounding each tooth is a radiolucent space representing the alveolar periosteum (periodontal membrane). Adjacent to this is a thin, dense structure composed of compact bone called the lamina dura (see Fig. 39-4).

The mandible is composed of two equal halves united anteriorly at the symphysis. Each half consists of a body extending from the midline backward in a roughly horizontal direction and a ramus at somewhat less than a right angle. The ramus is almost vertical; it articulates with the base of the skull by means of a condylar process that projects upward from the posterior aspect of the ramus. The other upward projection anteriorly is termed the coronoid process. The lower teeth are set in the mandibular alveolar process. The upper teeth are set in the alveolar process of the maxilla. The lower aspect of the maxillary antrum is visible on dental films of the upper teeth. The mental foramen, which transmits distal branches of the third division of the trigeminal nerve (V3) appears as a radiolucency below and between the lower bicuspids. The mandibular canal, which transmits the main trunk of V3, extends forward, parallel to the alveolar ridge, and is a radiolucency that should not be mistaken for disease (Fig. 39-5).

There are a few structures in the maxilla that also should be mentioned. The intermaxillary suture is observed in children and often in young adults. It appears as a midline radiolucent suture extending from the alveolar crest between the upper central incisors back to the posterior aspect of the palate. It may be interrupted in some areas. It has cortical margins that are smooth or slightly irregular. Usually there is no difficulty in differentiating it from a fracture. The incisive foramen (anterior palatine foramen) varies in size from a slit near the sagittal plane of the maxilla at about the level of the apices of the central incisors to a rather large round or oval foramen, usually clearly marginated and occasionally appearing somewhat bilobed. A radicular cyst, granuloma, or abscess, from which it must be differentiated, maintains its relation to the dental root in contrast to the foramen (see Dental Infections).

DENTAL INFECTIONS

Dental Caries

The presence of a “cavity” (or, more properly, dental caries) may escape detection by clinical methods of examination and yet be readily visible on a radiograph. Regardless of their cause, dental caries may lead to foci of infection involving the periapical tissues of the jaw and therefore are important lesions. On the roentgenogram a carious area is radiolucent and appears as an area of decreased opacity that is usually slightly irregular and may occur anywhere on the crown of a tooth or in its neck (Fig. 39-6).

Pulp Changes

The dental pulp contains the blood and nerve supply of the tooth. The cellular elements include odontoblasts and mesenchymal cells capable of differentiating into odontoclasts. Irritation caused by a number of external stimuli, including occlusal wear, dental caries, and minor trauma, may lead to formation of calcifications (pulp stones) or thickening

of the walls of the pulp chamber. There may be resorption with pulp chamber enlargement when infection is severe; this is caused by metaplasia with formation of odontoclasts.

of the walls of the pulp chamber. There may be resorption with pulp chamber enlargement when infection is severe; this is caused by metaplasia with formation of odontoclasts.

Periapical (Periradicular) Infections

All of the periapical inflammatory lesions represent chronic disease when they are advanced enough to produce roentgen changes. Chronic infection around the apex of a dental root is manifested by several changes that can be recognized and classified. The lesions may occur in the absence of clinical signs, which makes radiographic examination doubly important. Usually the infection follows the death of the pulp, and bacteria pass through the root canal into the periapical tissues.

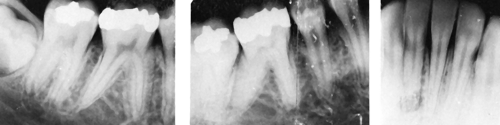

Condensing Osteitis

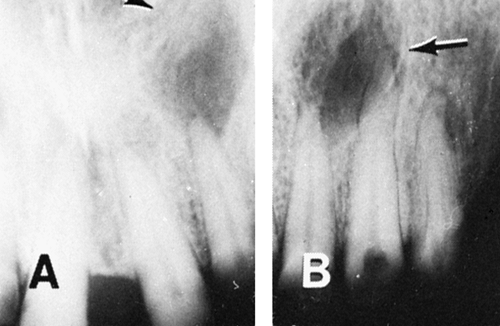

This condition may be caused by occlusal trauma or by infection, but it usually is associated with a pulp in the process of degeneration. It results in some thickening of the periosteum (periodontal membrane) at the apex of the root and is manifested on the roentgenogram by increased width of the radiolucent space between the lamina dura and the dental apex. The lamina dura is usually intact but may be thinned and partially resorbed (Fig. 39-7A). There is typically sclerosis surrounding the thickened periodontal membrane.9

Periapical Granuloma

This represents the chronic stage of periapical infection in which there is destruction of bone adjacent to the apex of the tooth. The resultant space is filled with granulation tissue. Roentgenographically there is a radiolucent zone, usually with clearly defined margins, which is located at the dental root apex. The lamina dura is usually destroyed, but the bony margin of the radiolucent zone is clearly outlined (see Fig. 39-7B). It should be realized that a granuloma, a radicular cyst, and an abscess may be similar roentgenographically and in many instances cannot be differentiated. Usually the granuloma is no more than 1 cm in diameter, much smaller than the usual radicular cyst.

Periapical Abscess

This is the stage of the disease in which there is actual suppuration. A radiolucent zone is noted around the apex of the tooth in this condition; the margin is somewhat irregular and poorly defined but may be sclerotic in disease of long duration. The lamina dura is destroyed in the area of the disease (see Fig. 39-7C).

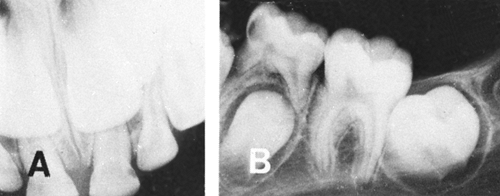

Radicular or Root Cyst

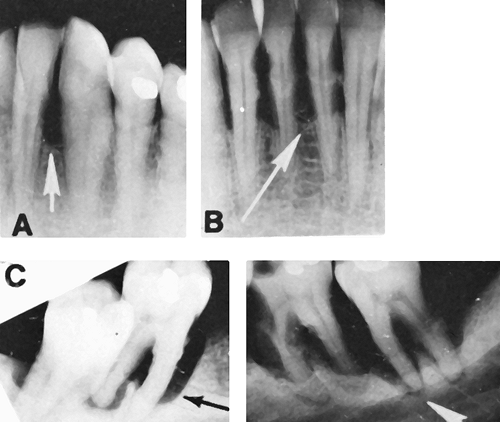

Proliferation of squamous cells frequently found in granulation tissue around a dental root apex is stimulated by chronic inflammation. This mass of epithelial cells breaks down to form a cyst-like cavity that gradually enlarges because of slow, constant pressure produced by the cellular proliferation. Eventually, a cyst wall is formed by dense fibrous tissue. Roentgen findings are those of a radiolucent area, which may be rather large, around the apex of one or more teeth. The margins are clearly defined, often with a thin layer of compact bone clearly outlining the cyst. A large cyst may expand the bone and displace contiguous teeth (Fig. 39-8).

The various manifestations of periapical infection may be difficult to classify into one of the groups described, but they should be recognized as lesions caused by infection; that is, they represent a focus of infection that must be managed by dental surgery. In a tooth so affected, the neurovascular supply

to the pulp is necrotic, and the dentist refers to the tooth as being nonvital.

to the pulp is necrotic, and the dentist refers to the tooth as being nonvital.

Alveolar (Periodontal) Infections

The earliest clinical manifestation of infection involving the alveolar tissues surrounding the teeth is gingivitis. The process begins with an accumulation of bacterial plaques on dental surfaces, which cause loss of the supporting structures because there is bacterial invasion of the gingival margins from the plaques. The accumulation of calculus above and below the gingival margin may play a role, but its relation to gingivitis is not clear. The infection progresses to the alveolodental periosteum, where chronic periostitis is produced. This results in absorption and destruction of bone surrounding the teeth, representing periodontitis (alveolar recession). When the process involves a single tooth and extends downward toward or to the apex it may be termed the vertical type of alveolar periodontitis. If the process is more generalized and results in destruction of the alveolar septa between several teeth, it is termed the horizontal type of periodontitis (alveolar recession).60

Radiographic Findings

The radiographic changes parallel the destructive process. At first there is some widening of the radiolucency between the root and the lamina dura at the neck, associated with some loss of the alveolar process. In the vertical type, the radiolucency around a single tooth increases. This indicates thickening of the periodontal ligament (membrane) and early bone involvement leading to loss of bony support and loss of the lamina dura. In the horizontal type, the alveolar ridge gradually disappears between the teeth until there is loss of bony support for several teeth. Roentgenographically, the presence of pus in these pockets of infection cannot be ascertained, but when the alveolar destruction is marked there usually is a considerable amount of local sepsis. Dense projections often appear at the necks of the affected teeth, representing calculus. Occasionally, root resorption occurs, resulting in loss of the root in one or more areas. This is manifested on the radiograph by an area of irregular radiolucency indenting the normally smooth surface of the involved root (Fig. 39-9).

DENTAL TRAUMA

Minimal trauma is a frequent occurrence, and there are no roentgen findings. If the pulp is damaged, it may be stimulated to lay down calcified scar tissue, which may fill the pulp chamber. Root resorption may also result from minor trauma. These changes can be observed roentgenographically. Trauma to a deciduous tooth may injure and thus impair the developing permanent tooth.43 The enamel may be

hypoplastic in some; in others, there is failure of narrowing of the pulp chamber, caused by degeneration of the pulp that cannot form dentin. A wide pulp chamber in an adult may be the result of childhood trauma. The opposite may also occur, for example, self-obliteration of the pulp by excess dentin deposition.

hypoplastic in some; in others, there is failure of narrowing of the pulp chamber, caused by degeneration of the pulp that cannot form dentin. A wide pulp chamber in an adult may be the result of childhood trauma. The opposite may also occur, for example, self-obliteration of the pulp by excess dentin deposition.

Various types of trauma that are important in children have been described. Complicated crown fractures or crown–root fractures expose the pulp. This makes prognosis poor for saving the tooth. In uncomplicated crown or crown–root fractures, the dentin is not exposed and prognosis is better. The root fracture that is usually missed clinically can be detected radiographically, but tomography may be required. Other complications of dental injury in children are failure of union, traumatic bone cyst, and apical cyst.

DENTAL MANIFESTATIONS OF GENERALIZED DISORDERS

In addition to outlining the teeth, intraoral dental films also include the alveolar process of the mandible, which may reflect changes in certain systemic diseases.

Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders

Hypopituitarism

Delayed dentition along with delay in osseous development is characteristic of hypopituitarism; dental films show the delay in development as well as the small, underdeveloped jaw. There is a delay in general skeletal development. There is also a delay in loss of primary teeth and development of permanent teeth. The teeth are normal in size.

Hyperpituitarism

In acromegaly and giantism there is an overgrowth of the mandible, so that the teeth are more widely separated than normal. The tongue is large and may protrude past the anterior teeth or past both teeth and lips. It also narrows the pharyngeal airway and may obliterate the valleculae. The greatest mandibular growth is in the incisor area. Rami may be normal or short. Radiographic study is helpful in differentiating this type of overgrowth from that associated with other conditions that produce abnormal enlargement of the jaw. Hypercementosis of the posterior teeth is common.

Hypothyroidism (Cretinism)

The delayed development of the teeth that occurs in this condition is associated with underdevelopment of the jaw. Primary teeth remain for several years beyond the normal time for exfoliation, and there is a comparable delay in appearance of permanent teeth. In myxedema (adult onset), no definite dental alteration is present.

Hypoparathyroidism

Hypoplasia of the enamel occurs when the onset of the disease is early in life, before the enamel is completely formed. Hypoplasia of the dentine may also occur if the hypoparathyroidism occurs before the dental roots are developed. This is manifested by short, underdeveloped roots. In pseudohypoparathyroidism, dental changes are similar to those in hypoparathyroidism: hypoplasia of the enamel; short, underdeveloped roots; and delayed eruption or noneruption of affected teeth.

Hyperparathyroidism

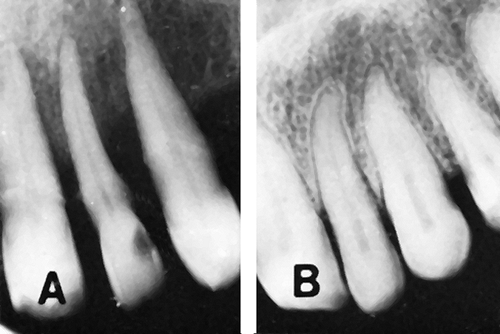

Thinning or loss of the lamina dura is noted on dental roentgenograms, along with marked decalcification of the alveolus. Dental films of the upper jaw also demonstrate a loss of the clearly defined outline of the bony floor of the maxillary antrum; this is also a result of decalcification (Fig. 39-10). In severe disease, cyst-like rarefactions may appear in the mandible. After successful removal of the tumor causing the parathyroid hyperfunction, the alveolus tends to return to normal and the lamina dura reappears. This disease is now discovered at a relatively early stage in most instances, so no radiologic changes may be observed in the alveolus.

Cushing’s Syndrome

Moderate decalcification of the alveolus is noted on the dental radiograph in this condition, along with partial loss of the lamina dura. As a result, this structure is sometimes difficult to outline, but there are usually some areas in which it can be observed.

Diabetes Mellitus

In severe diabetes, particularly in children, dental infection is a problem. Periapical as well as periodontal disease is commonly present and may be severe. These changes are readily outlined on dental radiographs, but they are not present in all patients and are nonspecific.

Hypophosphatasia

There is loss of alveolar bone, enlargement of the pulp chambers of the root canals, and a decrease in thickness of the enamel and dentine. The roots, therefore, are thin and have wide pulp cavities. Deciduous teeth are lost early because of the absence of cementum, without early eruption of permanent teeth (Fig. 39-11). Mild forms of the disease may produce no dental findings.

Developmental Disorders

Midline Facial Clefts

In cleft lip and cleft palate, there are dental anomalies ranging from deformity and malposition of some upper central teeth, to the presence of supernumerary teeth, to absence of a number of teeth. The films outline the osseous deformity as well as the dental alterations. A number of other isolated anomalies of the jaws and

teeth are clearly defined on occlusal films or on panoramic films of the mandible and maxilla. They include congenital hypoplasia or hyperplasia of the mandible and unilateral hypoplasia of the face.

teeth are clearly defined on occlusal films or on panoramic films of the mandible and maxilla. They include congenital hypoplasia or hyperplasia of the mandible and unilateral hypoplasia of the face.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

The characteristic dental alteration associated with this condition (dentinogenesis imperfecta type I) is replacement of the pulp canals by dentine, resulting in teeth that are uniformly dense. The finding of absent root canals is first observed in the incisor and the first molar teeth, which are the earliest to develop completely. This is an autosomal dominant trait. Osteogenesis imperfecta produces multiple fractures, blue sclerae, wormian bones, and impressive osteopenia.

Dentinogenesis Imperfecta Type II

This is an autosomal dominant trait that is unrelated to osteogenesis imperfecta. The deciduous and permanent teeth are brown and wear away rapidly. Dental roots are small and conical; small molars have single roots. The root canal may be very small and partially obstructed, and pulp is diminished or absent.

Amelogenesis Imperfecta

This is a disturbance that interferes with normal enamel formation. Both deciduous and permanent dentitions are affected. Most types of amelogenesis imperfecta are autosomal dominant or recessive, but some may be X-linked. There are may variants of this disorder, and they vary in appearance. Some produce squarish dental crowns with thin enamel of normal density with pits, or a normal thickness of enamel with the same density as dentine. Some produce enamel with less density than dentine on x-rays.

Osteopetrosis

The dense, ivory-like bone characteristic of this disease is noted in the alveolus; the roots of the teeth are often incompletely developed.

Achondroplasia

The delay in dental development in this condition is readily observed on roentgenograms of the teeth. Many of the teeth remain unerupted into adult life.

Ectodermal Dysplasia

This disease is characterized by partial or complete absence of hair, sweat glands, and teeth. The degree of dental abnormality ranges from complete dental aplasia to congenital absence of a few of the teeth.

Oculodento-osseous Dysplasia

Hypoplasia of the enamel is associated with microphthalmia, skeletal dysplasia and sclerosis, digital malformations, and, in some patients, calcification in the basal ganglia.

Trichodento-osseous Syndrome

Dental abnormalities consist of delayed or partial dental eruption with wide and long pulp chambers. Dental caries with multiple periapical abscesses and associated condensing osteitis are frequently present. The infant has dark, curly hair that may become straight by the second decade.

Taurodontism

This condition is characterized by short dental roots, enlarged pulp chambers, and elongated dental bodies. It is observed in about 20% of patients with Klinefelter’s syndrome.

Chondroectodermal Dysplasia (Ellis-van Creveld Syndrome)

This disorder is characterized by dysplasia of the fingernails, short stature caused by shortening of the tubular bones, polydactyly, carpal fusion, and dental abnormalities. Congenital cardiac abnormalities may also be present. There is usually a decreased number of teeth that are widely spaced and peg-shaped. Malocclusion is common; the mandible is always hypoplastic, and the undersurface often is markedly concave (antegonial notching).

Cleidocranial Dysostosis

Abnormal dentition and abnormality of the jaws are very common in this condition. There is often a delay in appearance of the teeth, with numerous supernumerary teeth. Permanent teeth are frequently malposed and fail to erupt. Absence or hypoplasia of the clavicles and anomalies of the cranial bones occur; numerous wormian bones are common.

Unilateral Hyperplasia of the Face

Unilateral Hyperplasia of the Coronoid Process

Hypercementosis (Exostosis of the Dental Root)

Cementum that is somewhat denser than cortical bone is produced and accumulates around the root of an affected tooth, usually a permanent one, to cause this abnormality. The premolars (bicuspids) are most commonly affected, followed by the first and second molars. Radiographic findings reveal an enlarged, bulbous, dense root that may be unusual in shape. The relationship of the lamina dura to the root does not change; it covers the abnormal root as in the normal state. The cause is not clear, and it may represent a dental anomaly.

Mandibulofacial Dysostosis (Treacher-Collins Syndrome)

The teeth may be malposed, widely separated, hypoplastic and displaced; malocclusion is common in this syndrome in which there is hypoplasia of the facial bones, particularly the zygoma and mandible. Cleft palate, absence of the palatine bones or high palate, and underdevelopment of paranasal sinuses and mastoids may also be observed on roentgenograms of the facial bones.35

Other Anomalies

There are a number of other developmental disorders in which abnormality occurs, but most are very rare. They include Rutherfurd’s syndrome, in which deciduous teeth are unerupted and absorb with permanent teeth visible below them.20 This is evidently caused by gingival hyperplasia of such an extent that eruption of the teeth is prevented. Oculomandibulodyscephaly (Hallermann-Streiff syndrome) is another rare condition in which teeth are malformed, erupt early and irregularly, and may be erupted at birth. The palate is high and narrow, and there is hypoplasia of the mandible.

Dental and jaw abnormalities may also occur in dysosteosclerosis, in which there is dental hypoplasia and the permanent teeth fail to erupt. Sclerosis of bone is noted in the base of the skull, ribs, and vertebral bodies. Micrognathia may be congenital and is associated with a number of syndromes; it is sometimes acquired secondary to trauma or infection. In juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, the mandible is often underdeveloped and a rather deep local notch may be observed on the undersurface of the mandibular body, just anterior to the angle (gonion). There is also a congenital form of notching (antegonial), which is a uniform concavity of the entire undersurface of the body of the mandible. Melnick-Needles syndrome causes radiographic alterations in the mandibular rami, with a thin medial cortex, and absence of the outer cortex produces cyst-like lesions. Coronoid processes are hypoplastic, and molar teeth are absent or impacted. Radiotherapy of the jaw in childhood may cause dental anomalies and hypoplasia, depending on the age of the child and the radiation dose.

Other causes of dental and jaw abnormalities include the mucopolysaccharidoses, chondrodystrophia calcificans congenita, hypotelorism, hypertelorism, Marchesani’s syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome, and various causes of retardation including trisomy 21. It is beyond the scope of this book to discuss all of these abnormalities.

Miscellaneous Disorders

Eosinophilic Granuloma (Histiocytosis X) of Bone

This lesion often involves the jaw, resulting in destruction of the area of bone affected, with no visible reaction. It is not unusual to observe the bone destroyed so completely that teeth are left with no visible bony supporting structure: so-called “floating” teeth. The bony lesions may be solitary or multiple within the mandible and may involve other bones. Several other diseases may destroy the mandible in a similar way; they include several of the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, metastatic neuroblastoma, and Ewing’s tumor. The teeth may appear to “float,” but there are often soft-tissue changes and other signs that tend to make the diagnosis. MRI using surface coils is helpful in defining the extent of bone and soft-tissue disease in these patients.

Acrosclerosis and Scleroderma

An increase in the thickness of the periodontal membrane results in uniform widening of the radiolucent space between the dental roots and the lamina dura. The uniform widening of this space in all of the teeth differentiates acrosclerosis and scleroderma from inflammatory disease of the alveolus, in which the widening is rarely uniform.

Osteomalacia

The decalcification caused by this disease is noted in the alveolus. The lamina dura is also involved; it is absent in some areas but usually can be visualized in others.

Rickets

A deficiency of vitamin D may cause dental disturbances as well as the classic skeletal abnormalities. Hypoplasia of the enamel is frequently observed because the disease usually occurs in young children and infants. When the onset is late, as in rachitis tarda, the development of the dental roots may be retarded. This is caused by defective dentine and cementum that may result in poor attachment of the teeth and lead to periodontal infection. The pulp chambers are abnormally large.

Renal Osteodystrophy

The dental findings are similar to those of hyperparathyroidism, with demineralization of the alveolus and loss of the lamina dura. In the child, delayed dental development is also observed.

Congenital Lead Poisoning

This condition may cause a delay in development of the deciduous teeth as well as typical lead lines in the long bones and increased density of the cranial vault.

CYSTS AND TUMORS OF THE JAW

Many lesions in the mandible can cause a local radiolucent defect. Some of these are defined clearly by a sclerotic rim

of bone, whereas others may have indistinct borders. Benign cysts and tumors are so similar to low-grade malignancies in the jaw that roentgen findings often are equivocal. In these instances, biopsy must be performed. It is worthwhile to describe these lesions, however, because at times they may be clearly differentiated on plain films.

of bone, whereas others may have indistinct borders. Benign cysts and tumors are so similar to low-grade malignancies in the jaw that roentgen findings often are equivocal. In these instances, biopsy must be performed. It is worthwhile to describe these lesions, however, because at times they may be clearly differentiated on plain films.

Dental Cysts

Periodontal (Radicular or Dental Root) Cysts

These cysts, which are the result of chronic periapical infection, were previously described in the Periapical Infections section. The cystic cavity is clearly defined and usually is unilocular. The relationship of the radiolucent cystic structure to the dental root is important in the differential diagnosis. This is the most common “cyst” of the jaw; all others are relatively rare.

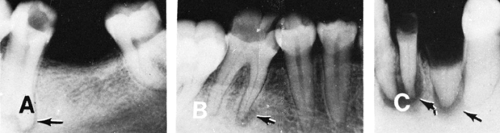

Follicular Cysts

This type of cyst arises in relation to a tooth follicle. Three forms may occur, depending on the cyst content: dentigerous cyst, simple follicular (primordial) cyst, and cystic odontoma.

The most common type of follicular cyst is the dentigerous cyst formed about the crown of a tooth. It develops around an unerupted, malposed tooth. Characteristically, it produces a sharply marginated, expansile, rarefied area with a formed or incompletely formed tooth projecting into the cavity along one side. Roentgen examination shows the large rarefaction, usually in the molar area, which causes expansion of the mandible. Its edges are clearly defined, and there is a tooth or a part of a tooth projecting into the radiolucent cyst (Fig. 39-12). These cysts may occur in the maxilla as well as in the mandible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree