Chapter 1 Introduction

No written records of the detection of fetal life exist in western literature until the 17th century. Around 1650 Marsac, a French physician, was ridiculed in a poem by a colleague, Phillipe le Goust, for claiming to hear the heart of the fetus ‘beating like the clapper of a mill’. It was not until 1818 that Francois-Isaac Mayor of Geneva, a physician, reported the fetal heart as audibly different from the maternal pulse heard by applying the ear directly to the pregnant mother’s abdomen. Laennec, a physician working in Paris around 1816, was the father of the technique of auscultation of the adult heart and lungs. Le Jumeau, Vicomte de Kergaradec (Fig. 1.1), also a physician working with Laennec, became interested in applying this technique to other conditions including pregnancy. John Creery Ferguson, later to become first Professor of Medicine at the Queen’s University of Belfast, visited Paris meeting Laennec and Le Jumeau. On his return to Dublin in 1827, Ferguson was the first person in the British Isles to describe the fetal heart sounds. He influenced Evory Kennedy, assistant master at the Rotunda Lying-in Hospital in Dublin, who wrote his famous work entitled Observations on Obstetric Auscultation in 1833. There was much argument over the technique of listening, some demanding the use of the stethoscope for reasons of decency only. At that time some doctors examined pregnant women through their clothing and this respect for the modesty of the woman must have inhibited the spread of obstetric auscultation. Anton Friedrich Hohl was the first to describe the design of the fetal stethoscope in 1834 (Fig. 1.2). Depaul modified this (Fig. 1.3) describing both in his Traite D’Auscultation Obstetricale in 1847. Although Pinard’s name is most commonly associated with the stethoscope his version followed several others, only appearing in 1876. Many papers were subsequently published in a variety of languages elaborating the technique. In 1849 Kilian proposed the ‘stethoscopical indications for forceps operation’: ‘The forceps must be applied under favourable conditions without delay when the fetal heart tones diminish to less than 100 beats per minute (bpm) or when they increase to 180 bpm or when they lose their purity of tone’. Winkel, in 1893, empirically set the limits of the normal heart rate at 120 bpm to 160 bpm. This has been carried forward for many years and reviewed in the light of the large amount of material produced by electronic recording.

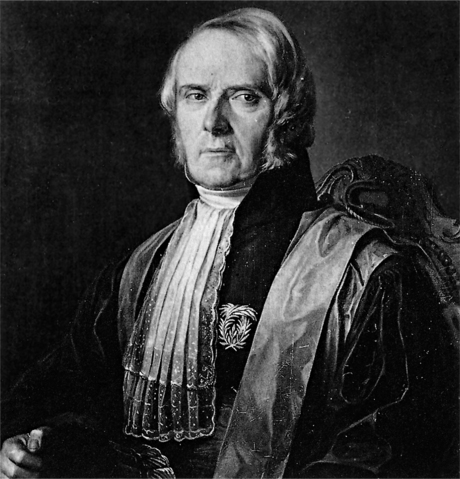

Figure 1.1 Jacques Alexandre de Kergaradec, robed as a Membre de l’Academie de Medicine Paris.

(With thanks to Professor J.H.M. Pinkerton, Emeritus Professor of Midwifery and Gynaecology, Queen’s University of Belfast)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree