CHAPTER 16 Introduction to inflammatory conditions of the small and large bowel

Introduction

Inflammatory disorders account for a significant proportion of bowel related disease. The two main inflammatory conditions – ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, which are collectively referred to as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) – affect up to 1 in 200 of the European and North American population between them (Kappelman et al., 2007). There are also a number of other inflammatory conditions that can affect the bowel, usually as part of wider systemic disease involving other organs, but these occur much less commonly (Table 16.1). This chapter will therefore largely focus on inflammatory bowel disease, although brief reference will be given to some of these other conditions.

Table 16.1 Inflammatory conditions affecting the bowel

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Connective tissue disease with gut involvement |

|---|---|

| Ulcerative colitis | Behçet’s |

| Crohn’s disease | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Microscopic colitis | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Systemic sclerosis | |

| Polyarteritis nodosum | |

| Wegener’s granulomatosis | |

| Henoch-Schönlein | |

| Sarcoid |

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative colitis, the slightly more common of the two conditions, causes inflammation of the colon, whereas Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth through to the anus. Both conditions tend to follow a chronic relapsing and remitting course and can lead to disabling symptoms and complications.

Studies have shown similar rates of IBD in Europe and North America where the estimated incidence of ulcerative colitis ranges from 8.8 to 13.4 new cases per 100 000 population per year, with slightly lower rates for Crohn’s disease of 5.6 to 8.6/100 000/year. The incidence of Crohn’s disease appears to be increasing, while that of ulcerative colitis is stable (Loftus et al., 2007). Rates of IBD in Africa and Asia are thought to be much lower, although limitations in case definition may have led to some underestimation. All age groups can be affected, although the condition is unusual in infancy, with the peak age of diagnosis occurring between the ages of 15 and 30 years, with a second peak between the ages of 50 and 80. Women and men are affected equally (Gunesh et al., 2008).

Genetic factors

It has been known for a long time that first degree relatives of patients with IBD are between 3 and 20 times more likely to develop IBD themselves and that the risk for twins with IBD was much higher (Thompson et al., 1996). A number of genes have now been identified to explain this observation and a complex picture is emerging with at least 30 different genes involved (Barrett et al., 2008). It seems likely that certain genes confer susceptibility to specific patterns of IBD, which becomes activated if other trigger factors arise. The best example and the gene about which most is known is the IBD1 or NOD2 gene, present on chromosome 16. Mutations of this gene have been shown to be associated with increased rates of Crohn’s disease involving the ileum. The gene itself codes for a protein that is involved in the interaction between the gut’s immune system and gut bacteria and it seems likely that Crohn’s disease can be triggered in an IBD1 individual who comes into contact with certain bacteria that they are unable to deal with effectively. Unfortunately, at the moment, the bacteria or group of bacteria involved have not been identified (Hisamatsu et al., 2003).

Environmental factors

The strongest evidence for an environmental trigger relates to cigarette smoking, which has intriguingly been shown to confer a risk of developing Crohn’s disease, while protecting individuals from ulcerative colitis. The mechanism of this effect has not been identified, but it is also recognized that Crohn’s disease can be more aggressive in smokers compared with non-smokers, whereas the converse is true in ulcerative colitis (Mahid et al., 2006).

Other environmental factors that have been suggested include the oral contraceptive pill and various dietary factors such as food additives, processed fats and refined sugars, although the evidence for most of these is limited (Reif et al., 1997).

Microbial factors

As with environmental factors, most of the early work in this field focused on trying to identify ‘the’ infective cause of IBD. Potential candidates included Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, which is known to cause a Crohn’s-like illness in cattle called Johne’s disease. However, this has always been controversial and, to date, no clear cause has been identified, despite large amounts of research, although it remains possible that M. paratuberculosis may play some part in the IBD story (Freeman and Noble, 2005). Other equally controversial studies have focused on the measles virus and the potential link between measles vaccine and Crohn’s disease (Thompson et al., 1995) but, once again, this association has not been confirmed. Consequently, recent research has tended to move away from looking at specific organisms and has focused on the interaction between the gut and the microflora of bacteria it contains. This shows potential as an area for research, although, like the field of genetics, the area is hugely complex; for example, it has now been shown that IBD patients are more likely to have received antibiotics in childhood (Hildebrand et al., 2008), which is just one of the many factors that could have an impact on gut flora.

Signs and symptoms

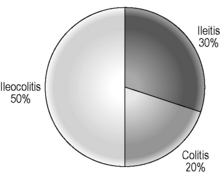

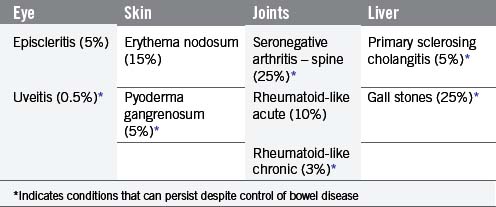

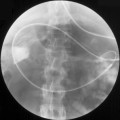

The signs and symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease largely depend on the site affected and the nature of bowel involvement at the site. Consequently, the symptoms of ulcerative colitis, which only involves the colon, are more predictable than those of Crohn’s disease, which can occur anywhere within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Figure 16.1). However, a number of patterns can be recognized. In addition, both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease can be associated with a number of symptoms that occur outside of the GI tract (Table 16.2), particularly when the disease involves the colon (Orchard, 2003).

Ulcerative colitis

The relapsing and remitting nature of UC means patients experience symptoms at times when the disease is active, commonly referred to as a flare, interspersed by periods without symptoms. Symptoms tend to build up gradually and often last for several weeks at a time. The severity of symptoms is at least in part explained by the extent of colon affected. The rectum is inflamed in all patients, but the extent of proximal colonic inflammation varies, with approximately 30% of sufferers having disease confined to the rectum, 40% with disease of the left colon and 30% developing total colonic inflammation (Jess et al., 2006). Individuals tend to follow the same pattern with each flare leading to inflammation in the same part of the colon, with only around 15% of patients experiencing extent progression over time.

Most patients with proctitis and left-sided colitis present with relatively mild or moderate symptoms with little or no systemic upset and are managed as outpatients, whereas patients with pan colonic involvement (Figure 16.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree