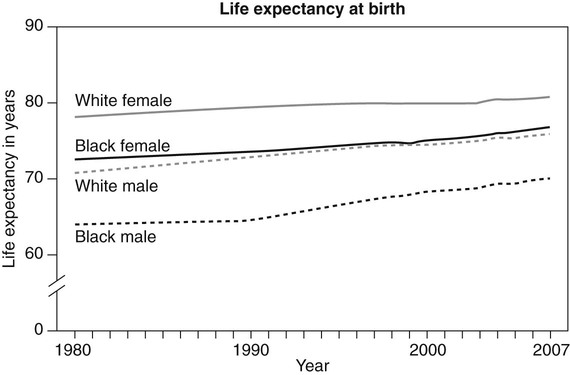

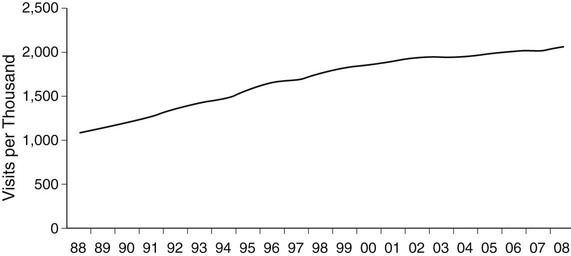

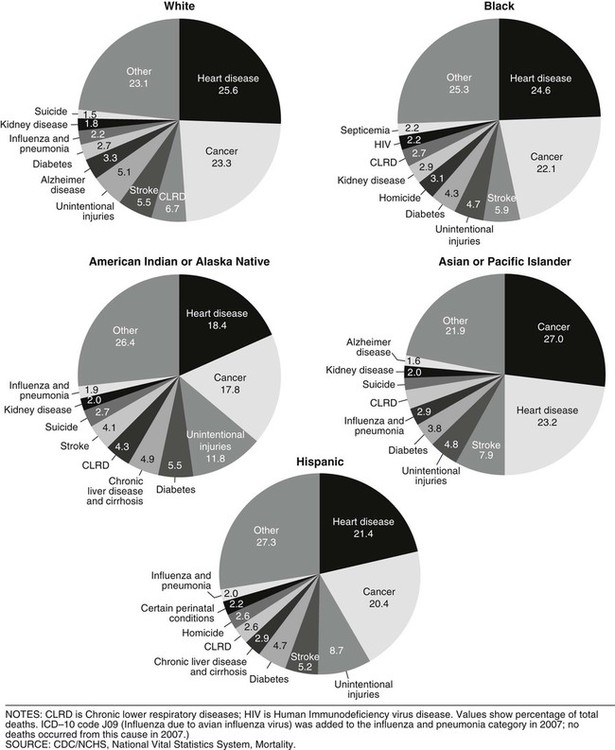

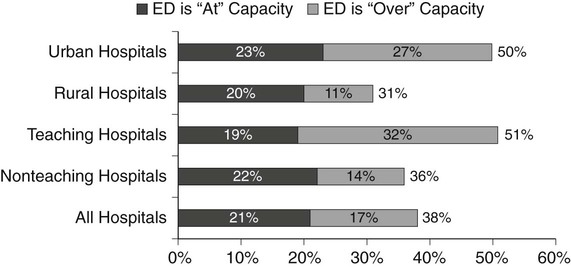

On completion of Chapter 1, the reader should be able to do the following: • Define common terminology associated with the study of disease. • Differentiate between signs and symptoms. • Distinguish between disease diagnosis and prognosis. • Describe the different types of disease classifications. • Cite characteristics that distinguish benign from malignant neoplasms. • Describe the system used to stage malignant tumors. • Identify the difference in origin of carcinoma and sarcoma. Over the past century, life expectancy in the United States has continued to increase. The majority of children born at the beginning of the twenty-first century are expected to live well into their eighth decade (Fig. 1-1). Over the past 100 years, the principal causes of death have shifted from acute infections to chronic diseases. These changes have occurred as a result of biomedical and pharmaceutical advances, public health initiatives, and social changes over the past century (Fig. 1-2). But experts disagree about the trend of increased life expectancy continuing into the twenty-first century. Some believe that increased knowledge of disease etiology and continued development of medical technology in combination with screening, early intervention, and treatment of disease could have positive results. However, many experts express concern about the quality of life of older adults. In other words, the possibility of older adults spending their added years in declining health and lingering illness, instead of being active and productive, is a concern. Mortality rates from any specific cause may fluctuate from year to year, so trends are monitored over a 3-year period. These data are used to evaluate the health status of U.S. citizens and identify segments of the population at greatest risk from specific diseases and injuries. Current data are available on the NCHS Web site and may be accessed at www.cdc.gov/. Health care delivery in the United States has two fundamental and diverse functions, with one area focused on healthy lifestyle for prevention and the second area focusing on restoration of health after a disease has occurred. Improvements in health care interventions such as technology, electronic communications, and pharmaceuticals have greatly contributed to a shift from inpatient services to outpatient services (Fig. 1-3). Ambulatory care centers range from hospital outpatient and emergency departments to physicians’ offices. In response to this shift, emphasis has been placed on increasing the number of physician generalists, including family practitioners, internal medicine physicians, and pediatricians. Inpatient admissions and hospital length of stay have remained fairly consistent over the past 10 years; however, emergency department visits have continued to steadily increase since the late 1990s, with many emergency departments reporting admissions exceeding their capacity (Fig. 1-4). The rate of growth in U.S. health expenditures is staggering. In 2010, U.S. health spending accounted for 17.3% of the gross domestic product, a larger share than in any other major industrialized country, with U.S. health care expenditures totaling $2.6 trillion (Table 1-1). The average annual health spending increase from 2010 through 2020 is projected to outpace average annual growth in the overall economy by 4.7%. The major sources of funding for health care include Medicare, funded by the federal government for older adults and disabled individuals; Medicaid, funded by federal and state governments for the poor; and privately funded health care plans. However, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) project that private insurance and out-of-pocket spending on health care will almost double to a rate of 4.8% in 2013. Estimates from the CDC National Health Interview Survey for 2010 indicated that approximately 16% of the U.S. population was uninsured at the time of the interview (Fig. 1-5

Introduction to Pathology

Monitoring Disease Trends

Health Care Resources

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Introduction to Pathology