Chapter 9 Knee and femur

The knee has a complex arrangement of ligaments, tendons and muscles which together provide stability to the joint. Because of the anatomical location and the complex biomechanics of the knee, it is susceptible to a variety of injuries.1 The knee and femur are often investigated in the event of trauma; however, this should only be the case if there is a suspected fracture, as ligamentous and meniscal injuries may appear normal on plain images.2 The knee should not be investigated for knee pain unless there is locking and restricted movement or a suspected loose body. Osteoarthritic changes are commonly found in the knee, and radiographic examination should only be undertaken if surgery is being considered.3

Plain radiography of the knee is undertaken less frequently in the 21st century as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the method of choice for imaging the joint structures. This is because of its high contrast sensitivity and multiplanar imaging capabilities. It is particularly effective in investigating the effects of trauma to the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments and menisci.4 The images of non-bony parts of the joint obtained by MRI are far superior to, and carry more information than, plain radiographs, and diagnosis and appropriate management of this complex joint is established with greater confidence after MRI examination.3

Ultrasound is also used as a method of imaging some lesions of the knee joint, e.g. Baker’s cyst; these can show as a vague mass behind the knee on plain X-ray images, but ultrasound will give a clear account of the full extent of the cyst.4

Fractures and injuries affecting the region of the knee and femur

Tibial plateau fracture

These fractures are often associated with considerable damage to the medial collateral or cruciate ligaments. The most common finding is depressed lateral tibial plateau caused by a car bumper injury; this is seen in 80% of cases.1

Anteroposterior (AP) knee – patient seated (Fig. 9.1A,B,C)

Positioning

• The patient is seated on the table with their legs extended

• The posterior aspect of the knee under examination is placed over the image receptor (IR)

• The unaffected leg is abducted from the leg under examination to clear it from the field of radiation

• A lead rubber apron is worn for radiation protection of the lower abdomen

• The leg is rotated to bring the tibial condyles equidistant to the IR. The patella may appear centralised but this is not consistent for all patients

Orthopaedic requests may require this projection to be undertaken with the patient erect, weightbearing. This allows for assessment of the joint space and alignment of the joint during weightbearing, prior to surgery.1 Its use has become more widespread in that published evidence suggests that a weightbearing technique has advantages over the conventional sitting method, and that a PA rather than an AP approach may be even better.5 Positioning for the erect AP remains the same as for the seated version, but with the patient standing with the back of their knee against the IR and still facing the X-ray tube. The stability of the patient should also be considered in the erect position and there should be a support for them to hold. The patient must be asked to distribute their weight evenly on both feet. Similarly, erect PA will require the patient to distribute their weight evenly, but with the patella in contact with the IR.

Beam direction and focus receptor distance (FRD)

Patient erect: Horizontal beam, at 90° to the IR or long axis of the tibia

Collimation

Lower third of femur, knee joint, proximal third of tibia, head of fibula, surrounding soft tissues

Criteria for assessing image quality

• Distal third of femur, proximal third of tibia, head of fibula, patella and soft tissue outlines are demonstrated

• Medial and lateral epicondyles of the femur are demonstrated in profile

• Head of fibula should appear partially obscured by the tibia

• Shafts of tibia and fibula should be separated

• Joint space should appear clear and the upper margin of the tibial plateau should be shown in profile

| Common errors | Possible reasons |

|---|---|

| The patella appears medially in relation to the femur and the proximal tibiofibular joint is demonstrated. The joint space may appear narrowed or obscured, unilaterally or bilaterally. Part, or all, of the tibial plateau does not appear to be seen in profile | The leg is excessively internally rotated; ensure the tibial condyles are equidistant from the IR and the patella is centralised. However, take care to note whether the patient has a naturally medially positioned patella or knock knees before attempting repeat projection. If the tibiofibular joint appears to be demonstrated correctly, and joint space shown clear, then it is likely that the patient’s patella does not naturally lie centrally positioned; an example of this is shown in Figure 9.1C |

| The patella is projected laterally in relation to the femur and the proximal tibiofibular joint is obscured by the tibia. The joint space may appear narrowed or obscured, unilaterally or bilaterally. Part or all of the tibial plateau does not appear to be seen in profile | There is excessive external rotation of the leg. Patellae are less likely to naturally lie on the more lateral aspect over the femur than medially, as above, but note should still be made to check if this is the case |

| There is no bony detail of the patella demonstrated – pale image of patella but femur may show trabecular detail outside the periphery of the patella | The radiograph is under-penetrated; increase kVp |

Lateral knee (Fig. 9.2A,B)

Positioning

• The patient is seated on the table with their legs extended

• The patient is rotated laterally onto the side under examination and the hip and knee are flexed; the lateral aspect of the knee is in contact with the IR. Flexion of the knee should be at least 45°, to a maximum of 80°. Generally flexion through 60° (making an angle of 120° between the femoral and tibial shafts) is most commonly adopted

• The unaffected leg is abducted away from the knee under examination to clear it from the field of radiation; this may be posterior or anterior to the knee under examination. If cleared posteriorly, it is more comfortable if the unaffected leg remains extended; if cleared anteriorly it is more comfortable for the knee and hip to be flexed

• The ankle of the affected leg is supported with a sandbag to bring the long axis of the tibia parallel to the table-top

• The condyles of the femur are superimposed; this may be achieved by placing the middle finger on the lateral condyle and the thumb on the medial condyle, rotating the patient’s femur until they are superimposed. Rotation at the pelvis may help with this adjustment

• The transverse plane of the patella is at 90° to the table-top

• A lead rubber apron is placed over the lower abdomen for radiation protection

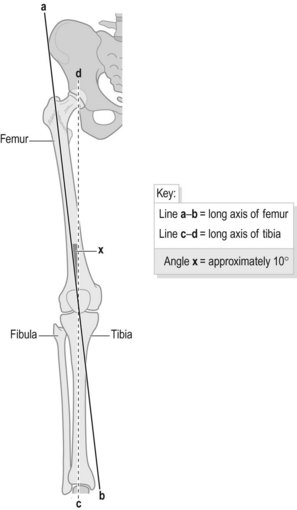

Comments on superimposing the femoral condyles

Criteria for assessing the lateral knee radiograph require the knee joint to be demonstrated with the condyles of the femur superimposed. However, there is often difficulty in producing this as the femur and tibia do not follow a straight line. The femoral shaft angles medially through approximately 10° from hip to knee, yet the plane of the articular surface of the knee joint is at right-angles to the long axis of the tibia (Fig. 9.3); this means that there is an angle of approximately 170° between femur and tibia at the lateral aspect of the knee joint. Therefore, when the patient is placed on their side for the lateral knee position, it is unlikely that a vertical central ray would travel through the joint at 90° or superimpose the femoral condyles. To correct this the lower leg needs to be raised from the table-top, with pads or sandbags, to ensure the tibia lies parallel to, and the tibial plateau is perpendicular to, the IR.6 Padding at the ankle end of the limb is likely to be most effective.

Without padding at the ankle the condylar surfaces will not lie in the same plane, and if padding is not used, some texts claim the solution is to apply a cranial angle of approximately 7° as compensation.7,8 If this method is used the main beam will be directed towards the gonads. It has been noted that some radiographers adapt the above technique by centring lower, in conjunction with a vertical central ray, to achieve the same effect as applying a cranial angle, but this will necessitate a larger collimated field of radiation and this is also not recommended. Indeed, this practice must be actively discouraged and is in contradiction of the requirements of IR(ME)R 2006.

Beam direction and FRD

Vertical at 90° to the IR and coincident with the transverse axis of the joint

In cases of trauma horizontal beam laterals must be performed; this method will demonstrate any joint effusion displacing the suprapatellar bursa, which may contain fat released from the bone marrow following fracture.2 A fat–blood effusion may be seen (lipohaemarthrosis), indicating a fracture even if not seen on the resulting radiograph. Use of a horizontal beam will also ensure that the unstable joint is not disrupted further, or fracture fragments further displaced. This is especially a risk in the case of transverse patellar fracture or fractures of the femoral shaft.

Collimation

Lower third of femur, knee joint, proximal third of tibia, head of fibula, surrounding soft tissues

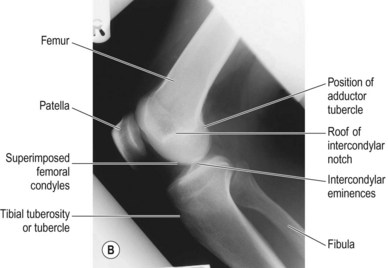

Criteria for assessing image quality

• Distal third of femur, proximal third of tibia, head of fibula and soft tissues should all be demonstrated

• Knee joint is demonstrated as clear, with the condyles of femur superimposed

• Patellofemoral joint space is demonstrated. However, if the patella is not naturally positioned centrally over the femur, the patellofemoral space will not be seen despite good superimposition of the femoral condyles. This is seen in Figure 9.2B

• Head of fibula is partly superimposed over tibia (approximately one-third to half of the head should be overlapped)

• Head of fibula is seen posteriorly in relation to tibia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree