Knee Joint and Calf

Anatomy and Techniques

Overview

Position 1: Anterior Knee

Technique

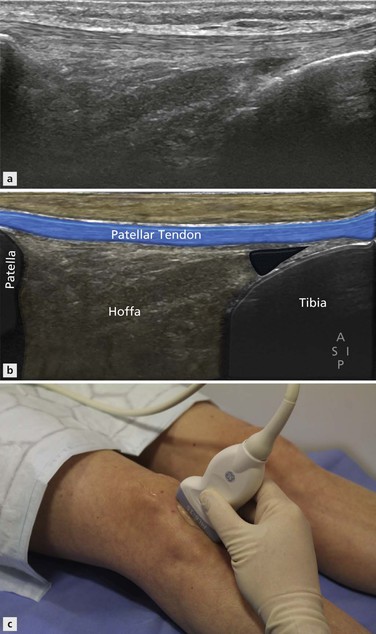

The patellar tendon is very readily assessed with ultrasound (Fig. 21.1). It has the striated predominantly reflective appearance typical of normal tendon tissue. The low-reflective areas represent the tendon fibres and the brighter material is the interspaced connective tissue. In long axis, the tendon measures approximately 5 cm. In cross section, it is considerably wider than it is thick, cross-sectional dimensions 26 × 4 mm are typical. It is convex in both its anterior and posterior margins. There is no tendon sheath but a paratenon is present.

The tibial enthesis is also accompanied by two bursae: the superficial and the deep infrapatellar bursa. Fluid is more commonly seen in the deep infrapatellar bursa. Gentle flexion and extension of the knee while examining the bursa in the axial plane makes the fluid more readily visible. The tendon’s superficial relationship is usually subcutaneous fat, although in its upper portion a small quantity of fluid may be identified in the prepatellar bursa and inferiorly in the superficial component of the infrapatellar bursa. The posterior relation of the patellar tendon is Hoffa’s fat pad. This has a bright reflective appearance typical of fat. It is fairly homogeneous, containing a few blood vessels only.

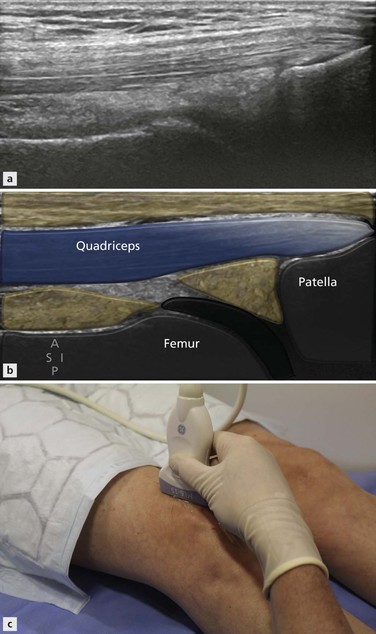

The other important tendon of the extensor mechanism is the quadriceps tendon. This has several components and care must be taken not to concentrate only on the most obvious central component. To demonstrate these different parts, it is best to begin with the probe in long axis centrally positioned over the upper border of the patella (Fig. 21.2). The typical bright, striated appearance of the central part of the tendon will be seen beneath. Often three or four distinct bands are visualized with interspaced reflective connective tissue. The upper bands represent the contribution from rectus femoris and the lower the components of vastus intermedius. There are contributions from vastus medialis and lateralis, which also have separate insertions on the superomedial and superolateral patella. With the knee fully extended, some kinks may be evident in the tendon, leading to areas of altered reflectivity. These disappear when slight flexion is applied, although the knee must be returned to full extension prior to assessing Doppler activity. Deep to the tendon, there is a triangle of fat, the suprapatellar fat pad. This fat pad is separated from the prefemoral fat by the synovial knee joint. A small quantity of fluid is not infrequently identified within the joint.

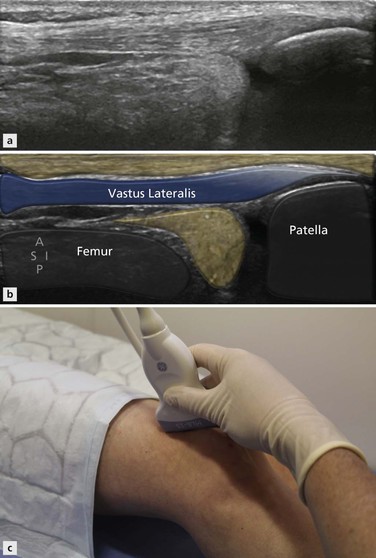

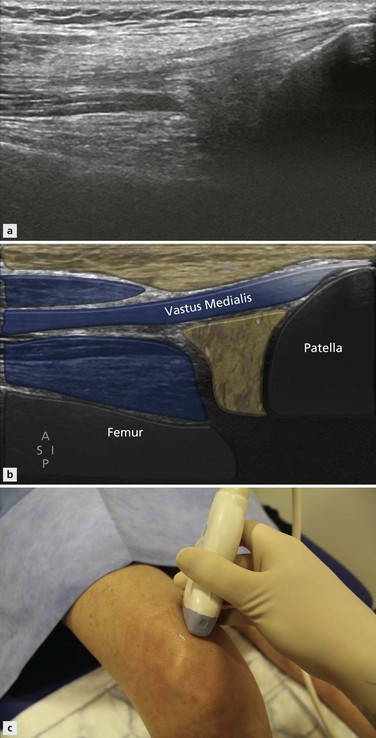

The probe is then moved laterally, the upper end of the probe a little more than the lower end, to align along the tendon of vastus lateralis (Fig. 21.3). This has a broader insertion along the superolateral aspect of the patella with fibres contributing to both the central tendon and the lateral retinaculum. The probe is finally moved medially, once again the proximal end more than the distal end, to align along the tendon of vastus medialis (Fig. 21.4). The musculotendinous junction of vastus medialis is lower than vastus lateralis and the tendon arises from the deep rather than the superficial component of its parent muscle. The muscle fibres visible here make up the vastus medialis obliquus.

Figure 21.3 Parasagittal approach to the supra patellar extensor mechanism for vastus lateralis insertion.

Figure 21.4 Parasagittal approach to the supra patellar extensor mechanism for vastus medialis insertion.

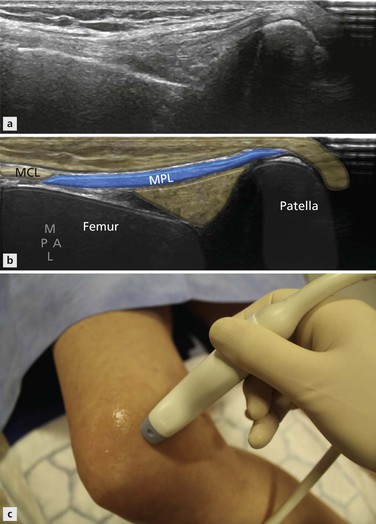

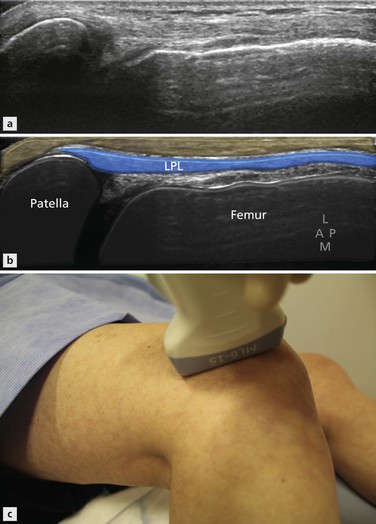

Both patellofemoral ligaments should be examined in turn and each followed posteriorly to where they form the medial collateral ligament and the ITB respectively. They are traced forwards to their insertions along the medial (Fig. 21.5) and lateral border of the patella (Fig. 21.6). The retropatellar surface can also be examined, although not in its entirety. The medial facet is easier to see and gentle medial pressure on the lateral border of the patella improves visualization. This is particularly useful when patellar dislocation is suspected and cartilage injury in this location may be found. The presence of fluid within the joint improves visualization. The patella can be tracked during flexion and extension using ultrasound, although more accurate techniques have been described particularly using MRI. Patellar maltracking is best assessed with the quadriceps under tension. This can be achieved either by attaching weights to the patient’s shin that they then have to lift or asking the patient to extend the knee against the resistance of the examiner’s hand.