KEY WORDS

Acardiac Acephalic Twin. One twin is malformed. No heart is present, and circulation is pumped from the second twin. Either partial or complete absence of the head with cystic hygroma.

Conjoined (Siamese) Twins. Twins that are joined at some point in their bodies.

Corpus Luteum Cyst. A cyst developing as a response to human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) in the first few weeks of pregnancy. Such cysts usually disappear by 14 to 16 weeks after the last menstrual period.

Cytomegalic Inclusion Disease (CMV). Viral disease characterized in utero by fetal ascites, intrauterine growth restriction, intrafetal calcification, and cardiac anomalies. The placenta is often enlarged.

Dizygotic Dichorionic. Twin pregnancies in which there are two nonidentical fetuses and two placentas.

Erythroblastosis Fetalis (Rh Incompatibility). A form of fetal anemia in which the fetal red cells are destroyed by contact with a maternal antibody produced in response to a previous fetus. Severe fetal heart failure results.

Fifth Disease. See Parvovirus.

Fraternal Twins. Dizygotic dichorionic nonidentical twins (Fig. 44-1).

Gestational Diabetes. A form of diabetes mellitus that manifests itself only in pregnancy. Discovered by performing a glucose tolerance test and associated with large babies.

Hydrops Fetalis. The fetal abdomen contains ascites, and the skin is thickened by excess fluid. This condition has a variety of causes, of which the most well known is Rh (rhesus) incompatibility. Other causes are associated with what is known as nonimmune hydrops (see Chapter 45).

Locking Twins. Because the twins are not separated by an amniotic sac membrane, they become entangled and are consequently difficult to deliver.

Macrosomia. Exceptionally large infant with fat deposition in the subcutaneous tissues; seen in fetuses of diabetic mothers.

Monochorionic Diamniotic. Identical twins in two amniotic cavities.

Monochorionic Monoamniotic. Identical twins in a single cavity.

Monozygotic Monochorionic. Twin pregnancies in which the fetuses are identical; usually an amniotic sac membrane divides the two amniotic cavities, but it may be absent.

Multiple Pregnancy. More than a singleton fetus (e.g., twins, triplets, or quadruplets).

Myometrial Contraction. Localized slow, asymptomatic contraction of the uterine wall. Re-examination after 20 to 30 minutes will show it to have disappeared.

Nonimmune Hydrops. Hydrops not related to underlying immunologic problems. There are many different causes. A cardiac origin is the most common.

Parvovirus. Viral disease characterized by severe fetal anemia. It may result in hydrops. It usually occurs in child care providers.

Polyhydramnios. Excessive amniotic fluid. Defined as more than 2 L at term.

Rubella. Viral disease occurring in utero with a number of associated fetal anomalies including congenital heart disease.

“Stuck” Twin. Massive polyhydramnios around one twin and severe oligohydramnios around the second. There is a shared placental circulation and one twin gets most of the blood supply. It is usually a fatal condition unless some of the amniotic fluid is withdrawn or if the connection between the twins’ vascular supply in the placenta is surgically interrupted.

Toxoplasmosis. Parasitic disease affecting the fetus in utero, often resulting in intracranial calcification.

Twin-to-Twin Transfusion Syndrome. When monozygotic twins share a placenta, most of the blood from the placenta may be appropriated by one fetus at the expense of the other. One twin becomes excessively large, and the other is unduly small.

VACTERL. Combination of findings seen mostly in diabetics. There are vertebral, anal, congenital heart, tracheoesophageal, renal, and limb findings.

The Clinical Problem

If the pregnancy appears clinically more advanced than predicted by dates, the sonographer should consider several detectable causes. Most commonly, the mother is wrong about her dates. Other possible causes of a uterus that is too large for dates include (1) polyhydramnios, (2) multiple pregnancy, (3) a large fetus, (4) a mass in addition to the uterus, and (5) a large placenta.

HYDRAMNIOS (POLYHYDRAMNIOS)

In polyhydramnios, there is excess amniotic fluid; consequently, the limbs stand out, separated by large, echo-free areas devoid of any fetal structures. Detailed sonographic visualization of the fetal gastrointestinal tract and the skeletal and central nervous systems is required because anomalies in these areas are associated with polyhydramnios (see Chapter 45). Other causes of polyhydramnios include maternal diabetes mellitus, multiple pregnancy, and hydrops. Isolated mild-to-moderate polyhydramnios at 20 to 30 weeks is common (about 3%) and often precedes macrosomia.

TWINS

It is important to establish whether there is a multiple pregnancy in a uterus that appears large for dates. Twins are at risk for a number of problems during pregnancy and have to be followed with serial sonograms to see that growth is adequate, that death has not occurred, and that one twin is not growing at the expense of the other. Careful sonographic examination of multiple pregnancy is necessary because the fetuses often adopt an unusual fetal lie. Additional fetuses, as in quintuplets, may be missed if careful scanning is not performed.

MACROSOMIA

Unduly large fetuses (over 4,000 g at birth) pose management dilemmas for the obstetrician because they are difficult for the mother to deliver. They are often the fetuses of diabetic or obese mothers. Weight estimation is important here because the obstetrician must decide whether to perform a cesarean section and must be alert to the delivery problems that occur with the fetuses of diabetic mothers.

MASS AND FETUS

Additional masses may give the impression that the uterus is larger than it really is, as with fibroids or ovarian cysts. Such problems are particularly important if an abortion is being considered because the clinician may incorrectly estimate the dates as being beyond the legal limits for abortion. Because fibroids cause a number of problems during pregnancy, such as spontaneous abortion and difficulty in delivery, size estimation and location of fibroids are important.

HYDATIDIFORM MOLE

Hydatidiform mole causes uterine enlargement in the first and early second trimester. This condition is described in detail in Chapter 39.

Anatomy

The following are important concepts to keep in mind regarding twins:

Amnionicity—the number of sacs

Chorionicity—the number of placentas

Monozygotic—single zygote that divides to form identical twins

Dizygotic—two zygotes that form fraternal twins

AMNIONICITY

Each sac is surrounded by an amniotic membrane, and each placenta gives rise to a chorionic membrane. In a dichorionic pregnancy—that is, one with two placentas—it is possible to see four “leaves” of the membranes that separate the fetuses (possible but, unfortunately, unlikely). Because these layers are difficult to separate, a subjective evaluation of the thickness is done; if only the amnions are present, the membrane is quite thin and may be difficult to see. No measurement of amniotic membrane thickness is used because the apparent thickness varies depending on the membrane angle to the ultrasonic beam. It is thickest at right angles to the beam. When there are two sacs and two placentas (diamniotic dichorionic), placental tissue often grows into the gap between the amniotic cavities, creating the “twin peak,” or lambda sign (Fig. 44-1A–C).

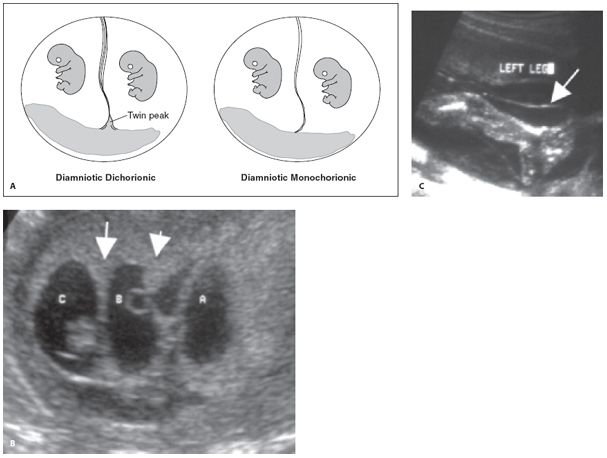

Figure 44-1. ![]() A. Diagram showing the two types of diamniotic pregnancy. In a dichorionic diamniotic pregnancy, four separate components make up the intervening membrane between the two cavities. There are separate chorionic and amniotic membranes from each pregnancy. In a dichorionic diamniotic pregnancy, the placenta grows into the gap between the two amniotic cavities forming the twin peak sign. The presence of the twin peak sign is strong evidence in favor of a diamniotic dichorionic pregnancy. In a monochorionic pregnancy, only two amniotic membranes make up the intervening membrane, so the membrane is thinner and has only two components. No twin peak sign will be seen in a monochorionic diamniotic pregnancy. B. Diamniotic dichorionic triplets. The twin peak or lambda sign is seen adjacent to the placenta (arrows). Note that the membrane looks thick elsewhere. C. Thin membrane with absent lambda sign in monochorionic diamniotic pregnancy. Note the thin membrane with only two components (arrow).

A. Diagram showing the two types of diamniotic pregnancy. In a dichorionic diamniotic pregnancy, four separate components make up the intervening membrane between the two cavities. There are separate chorionic and amniotic membranes from each pregnancy. In a dichorionic diamniotic pregnancy, the placenta grows into the gap between the two amniotic cavities forming the twin peak sign. The presence of the twin peak sign is strong evidence in favor of a diamniotic dichorionic pregnancy. In a monochorionic pregnancy, only two amniotic membranes make up the intervening membrane, so the membrane is thinner and has only two components. No twin peak sign will be seen in a monochorionic diamniotic pregnancy. B. Diamniotic dichorionic triplets. The twin peak or lambda sign is seen adjacent to the placenta (arrows). Note that the membrane looks thick elsewhere. C. Thin membrane with absent lambda sign in monochorionic diamniotic pregnancy. Note the thin membrane with only two components (arrow).

The most common type of twins are dichorionic diamniotic (about two thirds). In a monochorionic diamniotic pregnancy, there is a shared placenta, but there are two separate cord insertions, with each fetus in its own sac. In monochorionic monoamniotic pregnancies, there is a single common sac with no sac membrane visible (Fig. 44-2).

In dichorionic pregnancies, there may be adjacent placentas or two separate placentas. It can be difficult or impossible to tell a fused from an adjacent placenta, but it is important to try and make this distinction (Fig. 44-3).

Technique

When a patient is large for dates owing to a multiple gestation, the scanning routine changes. The first rule of finding twins is: look for the third. Woe be to the sonographer who gets caught up in the excitement of discovering twins and neglects to hook that femur up to trunk number three.

COUNTING AND ASSIGNING POSITION

The first order of business is to do a sweep through the uterus and count heads. Establish that each fetus has a beating heart, because there is a higher incidence of fetal death in multiple gestations. Next, assign a number or letter to each head, traditionally starting with the first to present—but not necessarily the lowest head. If both twins, for example, are cephalic, and twin A on the right is clearly lower, it still must be labeled as “A, right side,” because on the subsequent exam, it may be breech. With twins, this is easy; with more than two, follow the membranes and placentas and draw a map to assign the letters, so anyone can perform the follow-up work, and be sure to give the right set of measurements to each fetus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree