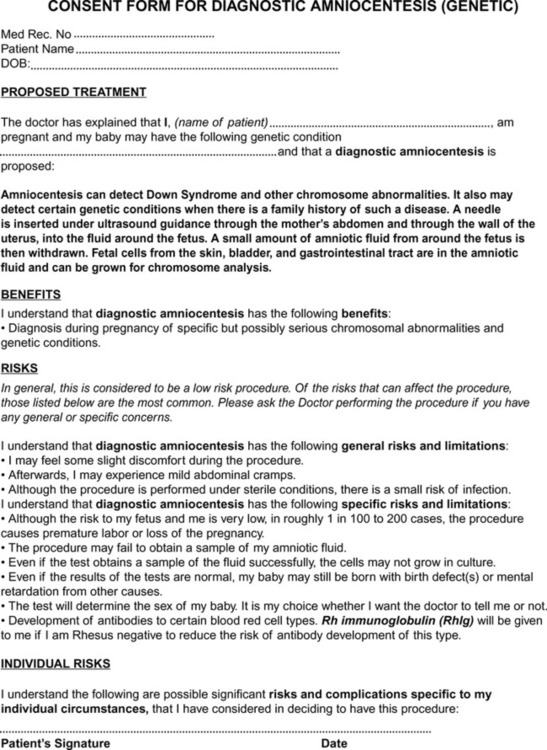

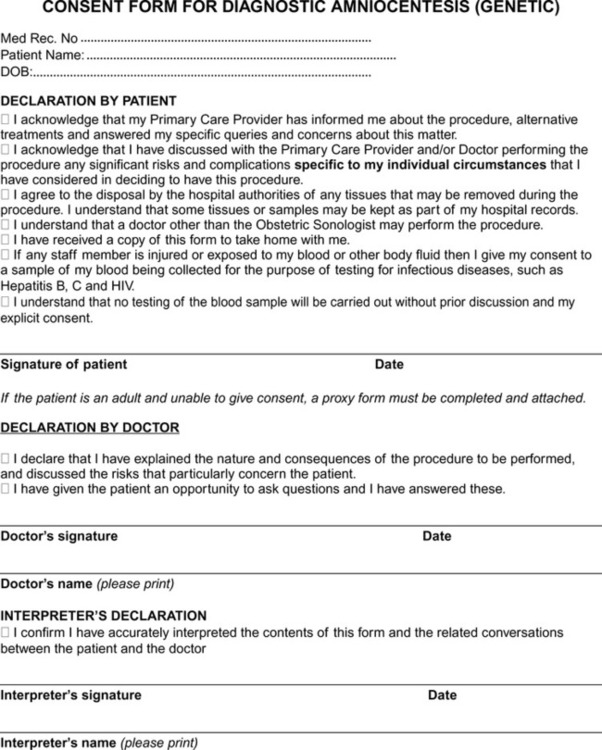

Students who successfully complete this chapter will be able to do the following: • Differentiate between statutory, administrative, and common law. • Define the term tort and cite examples that may involve sonographers. • Define the terms negligence, liability, and malpractice. • Explain the standard of care expected of a reasonably prudent sonographer. • Describe the different kinds of patient consent. • Identify situations in which employers or supervisors share liability. • Describe professional accountability. • Identify factors that contribute to a suit being instituted against a sonographer. • Discuss the steps sonographers should take to protect themselves against malpractice suits. • Explain the various aspects of giving a deposition and/or testifying for a legal proceeding. • State what important factors must be considered in purchasing professional liability insurance. • Describe ethical theories that may be used when working on ethical problems. • Explain how sociocultural factors affect ethical decision making. • Identify the recent trends in health care and society that have affected current ethical and legal issues. • Describe the sonographer’s role in relation to medical ethics. • Discuss the importance of professional confidentiality. • Explain the National Standard of Care required of sonographers. • Explain the ethical interaction between patients, peers, and other health care professionals. Sonographers should follow their professional scope of practice (available at http//:www.sdms.org) and should understand the concepts and mechanisms of law and the legal restrictions placed on health care. A basic knowledge of the law and how it works can help sonographers avoid litigation and allow them to practice their profession confidently. The underpinnings of the law are the following: 1. Intrusion on the patient’s physical and mental solitude or seclusion 2. Public disclosure of private facts 3. Publicity that places the patient in a false light in the public eye 4. Appropriation of the patient’s name or likeness for the defendant’s benefit or advantage Your employer’s policy and procedure manual should provide specific guidelines about what can be revealed without violating confidentiality. The recent HIPAA legislation has caused most hospitals, clinics, and physician offices to create or revise policies and procedures related to patient information. Privacy standards became mandatory for all hospitals, clinics, office practices, and other health care settings on April 14, 2003. On April 20, 2005, HIPAA Security Standards became effective. Complete information can be obtained online at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa. Informed consent can be either express or implied. Express consent is given by the patient either in writing or verbally (Box 7-1). Implied consent is neither written nor spoken by the patient but instead is understood from the circumstances surrounding the procedure at issue. For example, consent is implied for necessary procedures a surgeon may perform during the course of a surgery to which the patient granted express consent. Consent forms are useful tools to help inform patients about procedures and to document consent (Figure 7-1). The role of imaging professionals is to follow the established policies and procedures of their institution and to identify when informed consent is needed. Although the legal responsibility lies with the physician in charge, most facilities also have adopted policies requiring their staff to ensure that informed consent is obtained. A growing trend in many hospitals is the use of interactive programs that can take nervous patients through the consent process, step-by-step, explaining the invasive procedure or operation, its risks and benefits, and even answering the patient’s questions. One such program is called The Emmi Solutions Program (http//:www.emmisolutions.com/informed_consent_improvement.html).

Legal and Ethical Aspects of Sonography

Legal aspects of sonography

Defining the law

Torts

Intentional Torts

Informed consent

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree