Date

Primary author

Location

Event

1928

R. Wideroe

Baden, Switzerland

Developed photon beam radiation with high-frequency generator

1938

W. Hansen

Stanford, USA

Description of “rhumbatron” using a resonant microwave unit to accelerate electrons

1939

H. Boot & J. Randall

Birmingham, UK

Creation of “magnetron” using resonant microwave for radar during WWII

1939

R. & S. Varian

Stanford, USA

Creation of “klystron” using resonant microwave for radar during WWII

1948

W. Hansen

Stanford, USA

Development of microwave LINAC

1953

C.W. Miller, D.W. Fry

Great Malvern, UK

Development of micowave LINAC

1957

L. Leksell

Stockholm, Sweden

Treatment of patients with Gamma Knife

1983

O. Betti & V. Derechinsky

Buenos Aires, Argentina

LINAC radiosurgery with Talairach stereotactic localization

1984

M.D. Heifetz

Los Angeles, USA

Description of high-dose radiation with LINAC to small targets in the brain

1984

F. Colombo

Vicenza, Italy

Description of stereotactic LINAC radiosurgery system

1985

G.H. Hartmann

Heidelberg, Germany

Modified stereotactic localization to deliver multiple arc radiosurgery treatments

1985

M.S. Ginsberg

Miami, USA

First description of LINAC radiosurgery in the USA

1988

K. Winston & W. Lutz

Boston, USA

LINAC radiosurgery with phantom target device to check accuracy

1989

W.A. Friedman & F. Bova

Gainesville, USA

High-precision bearings to control patient and gantry movements to improve beam accuracy to 0.2 ± 0.1 mm

World War II drove the need for microwave technology for military radar equipment. Innovation in this field led to the development of the modern LINAC. LINACs produce photon beams very differently from the Gamma Knife. Instead of decay of cobalt, LINACs use a microwave generator to accelerate electrons within a waveguide. The waveguide bunches the electrons onto a portion of the wave, where they can be efficiently accelerated up to 99.9 % of the speed of light. Once the electrons reach their full accelerating potential, they collide with a heavy metal target. The energy generated from this collision is mostly lost as heat. However, a small percentage of the electrons pass near the large nuclei of the metal target, are deflected, and undergo a change in acceleration. This interaction results in the emission of a photon from the electron, i.e., electromagnetic radiation [9]. “Bremsstrahlung,” German for “braking radiation,” is used to describe the production of radiation from decelerating or “braking” electrons.

Once the photon beam is produced, it is limited by a primary collimator, passes through a flattening filter to improve the spatial uniformity of the beam, passes through two independent monitoring ionization chambers, and can then be collimated by a set of secondary and tertiary collimators [9]. The photon then transfers energy and ionizes atoms within tissue. These ionizing events lead to molecular changes. Photon beam radiotherapy differs from particle beam radiation which propagates particles such as protons, neutrons, pions, and heavy charged particles through tissue. These charged particles directly disrupt the atomic structure of the material they are traversing and thereby cause biological change [10]. The expense of particle beam units has partly driven the development of LINACs for radiosurgery.

In 1938, William Hansen at Stanford described the concept of accelerating electrons by passing them repeatedly through a resonant microwave cavity, gaining velocity on each pass. He called this a “Rhumbatron” [11]. It was only improvements of microwave generators, necessitated by World War II, that enabled this concept to become a reality. These discoveries, along with Harry Boot and John Randall’s creation of the “magnetron” in the UK and the Varian brothers’ development of the “klystron” in the USA, both in 1939 [8], led to the development of microwave LINACs in both the UK and the USA by 1945 [12]. All of these devices worked similarly to accelerate electrons. The groups led by Don Fry at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment and Hansen at Stanford both described clinically workable LINACs. Interestingly, the groups had little knowledge of each other’s work until the late 1940s [8].

LINAC and Radiosurgery

Shortly after World War II, Leksell first used the term radiosurgery [1]. This concept sprouted from an idea Leksell had discussed with Sir Hugh Cairns at the first Scandinavian neurosurgical meeting in Oslo after the war. He discussed his concerns about then-available neurosurgical techniques and his plans to mechanically direct a probe or narrow beam of X-ray or ultrasound into the brain to ablate pathways for pain alleviation. Cairns gave him a positive response and Leksell began systematically investigating ionizing beams [13]. He and his colleagues tested an orthovoltage X-ray tube and proton beam produced by the cyclotron in Uppsala, calling proton radiosurgery “stralkniven” (ray knives) [14]. They also considered LINAC as a potential radiation source. Ultimately, they constructed the “Gamma Knife” using cobalt radiation [15]. Leksell began treating patients in 1957 [3, 14]. Other investigators worked with particle beam radiosurgery systems in Berkeley and Boston [16, 17].

Early radiosurgery researchers were aware of the potential for LINAC in delivering targeted radiation. Larsson, the head physicist in the collaborative group at Uppsala University with Leksell, wrote in 1974, “The choice between the two alternatives, e.g., roentgen or gamma radiation, should be based on technical, clinical and economical rather than physical considerations. If radiation surgery will reach a position as a standard procedure, improved electron accelerators for roentgen production, adapted for the purpose, would seem a most attractive alternative” [18].

The initial LINACs developed in the UK and the USA used traveling-wave technology [8]. They were limited by relatively low beam energy, low radiation output due to inefficient waveguide design and limited microwave power, and restricted range of movement. These systems were also large, with the top of the gantry being approximately 4 m off the floor, to accommodate the accelerating waveguide. The next generation of devices achieved full isocentric rotation by mounting the accelerating structure to a gantry, allowing the radiation source to be rotated in a vertical plane about a single point. Also, by mounting the waveguide horizontally with magnetic beam deflection (beam bending), the next generation of LINACs had more manageable heights. The next major improvement came in 1968 when Knapp et al. developed the side-coupled standing wave structure which improved shunt impedances so that the total length of the accelerating structure was greatly reduced [19]. This development did away with the need for beam bending (which had its own problems) and still allowed for full isocentric rotation at a practical height [8]. Currently, the US and Japanese manufacturers use standing-wave technology, while the UK manufacturers continue to use traveling-wave technology.

All LINAC radiosurgery systems focus a collimated X-ray beam on a stereotactically identified target. The gantry of the LINAC rotates over the patient, producing an arc of radiation focused on the target. The patient couch is rotated in the horizontal plane and another arc is performed. In this manner, multiple noncoplanar intersecting arcs of radiation are produced. Like the Gamma Knife, the intersecting arcs produce a high target dose, with minimal radiation to the surrounding brain [3]. Along with the LINAC rectangular collimator, a set of secondary circular collimators of varying size are used to conform the beam [20].

Modifications of LINACs were necessary to perform radiosurgery including a system to rotate the couch in synchrony with the gantry, collimator development, and stereotactic localization [21]. Several factors made LINAC desirable for radiosurgery delivery. LINACs were used widely in the USA for conventional radiotherapy, and modifying the LINAC for radiosurgery was much more cost-effective than purchasing a Gamma Knife. Gamma Knife units at the time were only capable of delivering radiosurgery and could not deliver conventional radiotherapy when not being used for radiosurgery. Additionally, extracranial radiosurgery treatment was believed to be more feasible using LINACs. The theoretical benefits of LINAC discussed by radiosurgery leaders in the past have now become a reality.

Within 10 years of LINAC development, reports appeared on the use of external beam radiation for radiosurgery [12]. In 1983 Oswaldo Betti and Victor Derechinsky reported the development of a multibeam LINAC coupled with a Talairach stereotactic localization system in Buenos Aires [12, 22]. They used circular collimators that could be oriented in multiple coronal planes of a patient sitting in a moveable chair while attached to a rotating head frame [6, 22, 23]. Their system uniquely had the patient in a sitting position [3].

In 1984, a standard LINAC with small modifications was used by Heifetz et al. (with Marilyn Wexler’s physics contributions) to deliver high-dose radiation to small targets sparing normal brain, similar to Leksell’s Gamma Knife [24]. Simultaneously, a neurosurgeon, Federico Colombo, and a group of physicists led by Renzo Avanzo in Vicenza, Italy, reported their stereotactic LINAC radiosurgery system [25]. They wrote about radiosurgical dose schemes of 40–50 Gy over two fractions separated by 8–10 days for various intracranial targets of 2–4 cm in diameter [26, 27]. The dose gradient achieved compared well with Gamma Knife data [27, 28]. Hartmann et al. in Heidelberg, Germany, followed these achievements with the description of a modified stereotactic localization and positioning system to deliver multiple arc radiosurgery treatments [29]. They modified a Riechert–Mundinger stereotactic device, using laser lights to position the frame within the isocenter.

The first published work on LINAC radiosurgery in the USA came from the University of Miami in 1985 [30]. However, their system relied on the jaws of the treatment machine for beam collimation instead of the secondary collimation system described by Larsson et al. [18]. Their technique was regarded as fractionated, rather than single fraction. One of the first solutions for the requirement to spread out the radiation entrance path and minimizing treatment delivery time was described by Ervin Podgorsak at McGill University [31]. He and his colleagues modified a LINAC using extra collimators to define small circular fields and simultaneous gantry and couch rotations. Additionally, the couch and gantry were monitored from the control area, eliminating the need to enter the room during treatment [32]. Due to increased error rates with simultaneous gantry and couch rotation, most institutions have not adopted this system.

Concerned with error and quality control, Winston and Lutz published their work on multiple arc LINAC SRS in 1988 [33]. Their system included a phantom target device that could easily be used to check the accuracy of each patient treatment as well as to evaluate sources of error. They found a mechanical accuracy of their system of 0.5 ± 0.2 mm. They suggested that the major error in any radiosurgery system was the error of localization and not mechanical error [3]. In 1989, Friedman and Bova reported on LINAC radiosurgery system at the University of Florida [34]. A portable add-on stereotactic devise was coupled to the LINAC, and high-precision bearings in the device controlled all patient and gantry movements. As a result, the radiation beam accuracy was improved to 0.2 ± 0.1 mm. The accuracy of treatment delivery was further increased with imaging software improvements and the ability to fuse CT and MRI images [34].

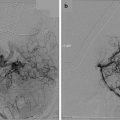

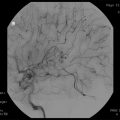

As LINAC radiosurgery became more prevalent, increasingly larger and more complex lesions were being treated (Fig. 9.1). The circular collimators were still useful for these types of lesions using a sphere packing technique (Fig. 9.2). An alternative approach to sphere packing was first described by Dennis Leavitt who built the first dynamic field shaping collimator for radiosurgery in 1989 [35]. The circular collimators were supplemented with independent rectangular vanes that “trimmed” the circular radiation field. This and other discoveries eventually led to the development of a micromultileaf collimator from Varian and BrainLAB [36]. These collimators have changed treatment delivery from multiple noncoplanar arcs to fixed static fields and dynamic arcs and allow for treatment of larger and more geometrically complex lesions.

Fig. 9.1

Conformal dose. Nonspherical lesions can be treated with minimal dose to surrounding structures. The colored lines are as follows: red = 70 % isodose, green = 50 % isodose, yellow = 20 % isodose

Fig. 9.2

Sphere packing technique. Dose planning has traditionally used the sphere packing technique originally developed by Lars Leksell. In this technique, sets of beams of radiation are aimed at the isocenter. The beams are selected to reach the isocenter via unique paths. The resultant dose distribution is spherical. To cover the entire target volume, the initial dose sphere is the largest sphere that fits inside the target volume. The target volume is then “packed” with equal or smaller diameter until adequate target coverage is achieved

LINACs are continuously being modified to improve radiosurgery delivery. For example, John Adler and Richard Cox at Stanford University reported the development of an industrial robot combined to a LINAC, called the Cyberknife® (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) [37]. This system can position a circularly collimated beam of X-rays to a target from a range of positions and angles. Moreover, the Cyberknife® uses room-mounted imaging to localize the treatment isocenter before treatment [38]. Other systems such as the Trilogy™ (Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) also localize the isocenter prior to treatment (Fig. 9.3) [39]. Real-time imaging of patients can be used to readjust beam coordinates for the target, making treatment of extracranial sites such as spine and abdomen possible [12, 20]. Spinal radiosurgery is being implemented for benign and malignant tumors, overcoming the tremendous difficulty of target localization in an area with movement of multiple joints [40–43]. In addition to modifications to collimation and target localization, LINACs have been modified to deliver SRS with intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) [12]. LINACs provide tremendous possibilities for unique approaches to treatment. These systems demonstrate the versatility of LINAC for radiosurgery.

Fig. 9.3

The Trilogy™ system. This system includes inline CT for target localization prior to treatment allowing for extracranial radiosurgery targeting

Radiosurgery for Benign Tumors

SRS has proved useful for the treatment of a variety of benign intracranial neoplasms. These tumors commonly arise from the skull base, where their dramatic impact on quality of life belies their benign histology and small size. Despite progressive improvement in microsurgical techniques, outcomes for patients with these difficult tumors continue to be less than optimal [44–46]. A significant amount of experience has been accumulated using SRS in the treatment of schwannomas and meningiomas. We will focus on each of these tumor types in turn.

Vestibular Schwannomas

Among benign intracranial tumors, vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuroma) has been one of the most frequent targets for SRS. This common tumor (representing approximately 10 % of all primary brain tumors) is a benign proliferation of Schwann cells arising from the myelin sheath of the vestibular branches of the eighth cranial nerve. These tumors are slightly more common in women, present at an average age of 50 years, and occur bilaterally in patients with neurofibromatosis (NF) type 2.

Leksell first used SRS to treat a vestibular schwannoma in 1969 [47]. SRS is a logical alternative treatment modality for this tumor for several reasons. A vestibular schwannoma is typically well demarcated from surrounding tissues on neuroimaging studies. The sharp borders of this noninvasive tumor make it a convenient match for the characteristically steep dose gradient produced at the boundary of a radiosurgical target. This allows the radiosurgeon to minimize radiation of normal tissue. Excellent spatial resolution on gadolinium-enhanced MRI facilitates radiosurgical dose planning. These tumors typically occur in an older population that may be less fit for microsurgical resection under general anesthesia. Finally, the location of these tumors at the skull base in close proximity to multiple critical neurologic structures (i.e., cranial nerves, brain stem) leads to appreciable surgical morbidity and rare mortality even in expert hands. This makes the concept of an effective, less invasive, less morbid alternative treatment that can be performed in a single day under local anesthesia quite attractive. Whether or not radiosurgery fits this description has been extensively debated.

Certainly, the role of radiosurgery is limited by its inability to expeditiously relieve mass effect in patients for whom this is necessary. The radiobiology of SRS also requires lower, potentially less effective doses for higher target volumes in order to avoid complications. This limits the use of SRS to the treatment of smaller tumors. Despite these limitations, there is substantial literature demonstrating radiosurgery is a safe and effective alternative therapy for acoustic schwannomas.

Spiegelmann et al. have reported their experience in 44 VS patients treated with LINAC SRS from 1993 to 1997 [48]. CT scanning was selected as the stereotactic imaging modality for target definition. A single, conformally shaped isocenter was used in the treatment of 40 patients; two or three isocenters were used in four patients who harbored very irregular tumors. The radiation dose directed to the tumor border was the only parameter that changed during the study period: In the first 24 patients who were treated the dose was 15–20 Gy, whereas in the last 20 patients the dose was reduced to 11–14 Gy. After a mean follow-up period of 32 months (range, 12–60 months), 98 % of the tumors were controlled. The actuarial hearing preservation rate was 71 %. New transient facial neuropathy developed in 24 % of the patients and persisted to a mild degree in 8 %. Radiation dose correlated significantly with the incidence of cranial neuropathy, particularly in large tumors (≥4 cm3).

Fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy (FSRT) has been used as an alternative management for vestibular schwannomas. This method is proposed as a way of exploiting the precision of stereotactic radiation delivery to minimize dose to normal brain while employing lower fractionated doses in an effort to minimize complications. Litre et al. recently reported on their experience with 155 VS patients treated with fractionated LINAC SRS [49]. The patients received five fractions of 1.8 Gy weekly for a total central dose of 55 Gy. Local tumor control rates were 99.3 % at 3 years, 97.5 % at 5 years, and 95.2 % at >7 year follow-up. Tinnitus (70 %), vertigo (59 %), imbalance (46 %), and ear mastoid pain (43 %) greatly improved post SRS. Complications included facial numbness (3.2 %), facial weakness (2.5 %), worsened tinnitus (2.1 %), and need for ventriculoperitoneal shunt (2.5 %). Thus far, most radiosurgeons feel that optimal results can be achieved with highly conformal single-fraction radiosurgery while sparing the patient the inconvenience of a prolonged treatment course.

Friedman et al. performed an analysis of 390 VS patients treated with LINAC SRS at University of Florida (UF) from July 1988 to August 2005 [50]. With a median follow-up of 32 months for the entire group, most tumors were unchanged or smaller (Figs. 9.4 and 9.5), and only 11 (4 %) tumors were larger. The 1- and 2-year actuarial control rates were both 98 %, and the 5-year actuarial control rate was 90 %. Four patients (1 %) required surgery for tumor growth. Seventeen patients (4.4 %) reported facial weakness and 14 patients (3.6 %) reported facial numbness after SRS. The risk of these complications rose with increasing tumor volume or radiosurgical dose to tumor periphery. Since 1994, when doses were deliberately reduced to 1,250 cGy, only 2 patients (0.7 %) experienced facial weakness and only 2 patients (0.7 %) developed facial numbness. Based on this and previous studies, the authors currently recommend a peripheral dose of 12.5 Gy for almost all acoustics as that dose most likely to yield long-term tumor control without causing cranial neuropathy.

Fig. 9.4

Pretreatment MRI scan shows left-sided vestibular schwannoma

Fig. 9.5

Four years after treatment, the MRI scan shows the schwannoma of Fig. 9.4 to be much smaller

Recently, van de Langenberg et al. described 37 VS patients treated with LINAC SRS with a 4-year probability of no additional intervention of 96.4 % ± 0.03 [51]. Median follow-up was 40 months and 65 % patients demonstrated tumor shrinkage, 22 % had stable VS size, and 13 % had growth. In 54 % of all patients, transient tumor swelling was observed.

LINAC SRS is a well-described effective treatment for smaller VS tumors and has a lower complication rate compared to surgery.

Meningiomas

Meningiomas are the most common benign primary brain tumor, with an incidence of approximately 7/100,000 in the general population. Surgery has long been thought to be the treatment of choice for symptomatic lesions and is often curative. Many meningiomas, however, occur in locations where attempted surgical cure may be associated with morbidity or mortality, such as the cavernous sinus or petroclival region [52, 53]. In addition, many of these tumors occur in the elderly, where the risks of general anesthesia and surgery are known to be increased. Hence, there is interest in alternative treatments, including radiation therapy and SRS, either as a primary or as an adjuvant approach.

Simpson, in a classic paper, described the relationship between completeness of surgical resection and tumor recurrence [54]. A grade I resection, which is complete tumor removal with excision of the tumor’s dural attachment and involved bone, has a 10 % recurrence rate. A grade II resection, complete resection of the tumor and coagulation of its dural attachment, has up to a 20 % recurrence rate. Grade III resection is complete tumor removal without dural resection or coagulation. Grade IV resection is subtotal, and grade V resection is simple decompression. Recurrence rates in grades IV and V groups basically reflect the natural history of the tumor, with high rates of recurrence over time. Unfortunately, some common meningioma locations, such as the cavernous sinus or petroclival region, are not readily amenable to a complete dural resection or coagulation strategy because of location and the proximity of vital neural and vascular structures. In addition, relatively high complication rates have been described for meningioma surgery in some locations and in the elderly.

Pollock and colleagues recently analyzed 198 patients with meningiomas less than 35 mm in diameter treated with either surgical resection or Gamma Knife radiosurgery [55]. Tumor recurrence was more frequent in the surgical resection group (12 % vs. 2 %). No statistically significant difference was detected in the 3- and 7-year actuarial progression-free survival rate between patients with Simpson grade 1 resections and those who underwent radiosurgery. Progression-free survival rates with radiosurgery were superior to Simpson grades 2, 3, and 4 resections. Complications were lower in the radiosurgery group.

Multiple LINAC SRS series have been published [56–59]. Hakim and colleagues described one of the largest such series, and the only one to report actuarial statistics [60]. One hundred twenty-seven patients with 155 meningiomas were treated. Actuarial tumor control for patients with benign tumors was 89.3 % at 5 years. Six (4.7 %) patients had permanent radiation-induced complications.

The University of Florida report on LINAC SRS treatment of meningiomas is one of the largest yet published [61]. Two hundred and ten patients were treated from May 1989 to December 2001. All patients had follow-up for a minimum of 2 years, and no patients were lost to follow-up. Actuarial local control for benign tumors was 100 % at 1 and 2 years and 96 % at 5 years (Figs. 9.6 and 9.7). Actuarial local control for atypical tumors was 100 % at 1 year, 92 % at 2 years, and 77 % at 5 years. Actual control for malignant tumors was 100 % at 1 and 2 years but only 19 % at 5 years. Permanent radiation-induced complications occurred in 3.8 %, all of which involved malignant tumors. These tumor control and treatment morbidity rates compare well with all other published series.

Fig. 9.6

A patient with known breast carcinoma presented with symptomatic pontine lesions. She was treated with radiosurgery (16 Gy to the 80 % isodose line)

We found that reliance on imaging characteristics rather than surgical pathology did not yield a high incidence of missed diagnoses. During the time interval of this study, only two patients were treated as presumed meningiomas and later found to have other diagnoses. One had a dural-based metastasis that was surgically excised when it enlarged. The other had a hemangiopericytoma of the lateral cavernous sinus that was surgically excised when it enlarged.

Han et al. recently compared LINAC SRS to fractionated radiation in the treatment of skull base meningiomas. A total of 220 skull base meningiomas were treated using SRS (n = 55), hypofractionated stereotactic radiation therapy (hFSRT) (n = 22), and FSRT (n = 143). Median follow-up was 32 months, and the median tumor volumes were 2.8 cm for SRS, 4.8 cm for hFSRT, and 11.1 cm for FSRT. The median treatment doses were 1,250 cGy in one fraction for SRS, 2,500 cGy in five fractions for hFSRT, and 5,040 cGy in 28 fractions for FSRT. Radiographic control was achieved in 91 % of SRS patients, 94 % of hFSRT patients, and 95 % of FSRT patients. The authors concluded that there was no differences in clinical or radiologic response to the different radiation strategies, although these data are limited due to variability of patients within each group and the slow growing natural history of skull base meningiomas [62].

One of the advantages of LINAC SRS is the flexibility of the system to treat systemic lesions. Increasingly, radiosurgeons are reporting on their experiences with treating spinal meningiomas with SRS. Recently, Gerszten et al. described the treatment of 45 benign spine tumors with LINAC SRS and CT for target localization [63]. They treated 14 cervical, 12 thoracic, 14 lumbar, and 5 sacral tumors. The majority of the tumors (91 %) were intradural. The mean maximum dose to the tumor volume was 16 Gy (12–24 Gy) given in a single fraction in 39 cases. Median follow-up was 32 months. Of the 19 (42 %) patients who had pretreatment pain, 15 had significant improvement after SRS. Of the 15 patients with a neurologic deficit pretreatment, four motor deficits were stable, one motor deficit worsened in patients with NF 1, 10 sensory deficits improved, and one sensory deficit worsened in a patient with NF 1.

Longer follow-up in these patients will be necessary for an accurate assessment of the efficacy of SRS for spinal benign tumors.

Radiosurgery for Malignant Tumors

Malignant tumors are radiobiologically more amenable to fractionated radiotherapy than benign lesions. Malignancies tend to infiltrate surrounding brain, resulting in poorly definable tumor margins. A priori, these two traits of cerebral malignancies would seem to make SRS an unattractive treatment option. Nevertheless, SRS has proved to be a useful weapon in the armamentarium against malignant brain tumors. The most common applications of SRS to malignant tumors are the treatment of cerebral metastases and the delivery of an adjuvant focal radiation “boost” to malignant gliomas.

Cerebral Metastases

Metastatic brain tumors are up to ten times more common than primary brain tumors with an annual incidence of between 80,000 and 150,000 new cases each year [64]. Fifteen percent to 40 % of cancer patients will be diagnosed with a brain metastasis during the course of their illness. Once a brain metastasis has been diagnosed, the median life expectancy is less than 1 year; however, in many patients, aggressive treatment of metastatic disease has been shown to restore neurologic function and prevent further neurologic manifestations. Debate exists concerning the optimum treatment for metastatic brain disease.

In autopsy series, brain metastases occur in up to 50 % of cancer patients [65]. Approximately 30–40 % of patients present with a solitary metastasis. Brain metastases frequently cause debilitating symptoms that can seriously impact the patient’s quality of life. With no treatment or steroid therapy alone, survival is limited (1–2 months). Whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) extends median survival, but the duration of survival is typically low (3–4 months). Several randomized trials have suggested that, when possible, surgery followed by WBRT is superior to WBRT alone. Patchell et al. reported a randomized clinical trial involving 46 patients with a single metastasis and well-controlled systemic disease [66]. They found a significant improvement in survival (40 vs. 15 weeks) and local recurrences in the CNS (20 % vs. 52 %) for patients in the surgery plus WBRT arm of the study. Likewise, Noordijk et al. randomized 66 patients and found a significant survival advantage (10 vs. 6 months) for the combination therapy arm [67]. In contrast, Mintz et al. studied a group of 84 patients and did not show an advantage of surgery plus radiotherapy over radiotherapy alone [68]. It has been suggested that the inclusion of a higher percentage of patients with active systemic disease and lower performance scores did not allow the benefit of improved local control to affect survival in this series.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree