Chapter 17 Lumbar Provocation Discography/Disc Access

Note: Please see page ii for a list of anatomical terms/abbreviations used in this book.

Since the description of the lumbar intervertebral disc as a potential source of spine pain by Mixter and Barr in 1934, the intervertebral disc has been the focus of spine-based care. Unfortunately, radiographic imaging has a potential limitation when it comes to the spine. Imaging studies such as plain radiographs, computed tomography scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging can demonstrate anatomic abnormalities, but they cannot definitively identify the source of spine-based pain.1–5 Lumbar provocation discography potentially provides a method for obtaining pain-generation data with regard to the intervertebral disc. Most importantly, data collection includes pain provocation (i.e., none, discordant, or concordant) correlated with the patient’s clinical scenario. Also, it includes manometry (pressure at pain provocation), contrast volumes, and disc architecture (nucleogram, post-discography CT).

We recommend using an introducer-needle technique using either an 18-g with 22-g or 20-g with 25-g although a single needle technique may be used. The needle tip can be modified as described in Chapter 2 or 18 to optimize needle navigation. It is currently accepted to have the needle entry be contralateral to the more painful side, unless there are prohibiting issues. Multiplanar imaging will be used to best advance the needle into its final position. Chapter 18 is dedicated to describing the variance in technique and the “tricks” to approach the L5-S1 disc when the iliac crest makes access more challenging.

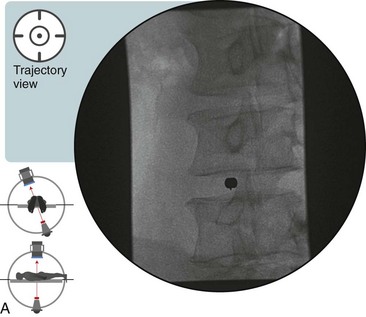

Trajectory View

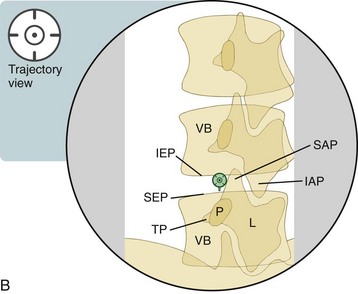

Trajectory View

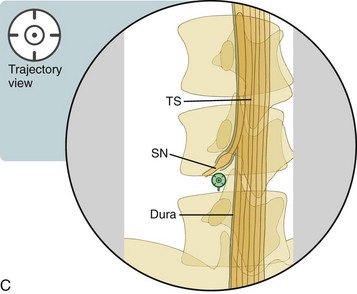

![]() Trajectory View Safety Considerations

Trajectory View Safety Considerations

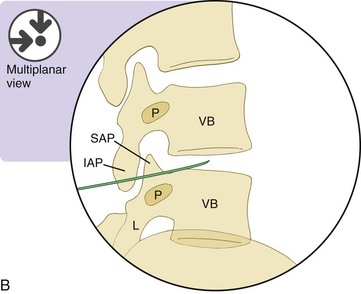

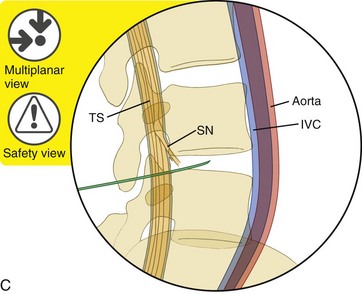

Remain immediately lateral to the SAP inferior base and rostral to the SEP, i.e., “low in the hole” at the SAP/SEP junction.

Remain immediately lateral to the SAP inferior base and rostral to the SEP, i.e., “low in the hole” at the SAP/SEP junction.

Superior or lateral migration can contact the spinal nerve.

Superior or lateral migration can contact the spinal nerve.

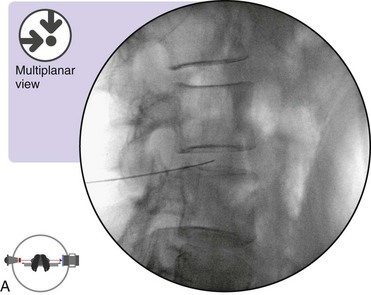

While advancing the needle toward the disc, do not drive too far medial until entering the disc. A medial straying needle can enter the dura and TS.

While advancing the needle toward the disc, do not drive too far medial until entering the disc. A medial straying needle can enter the dura and TS.

![]() Notes on Positioning in the Trajectory View

Notes on Positioning in the Trajectory View

For each level, setup is individualized by changing the oblique angulation and tilting of the image intensifier.

For each level, setup is individualized by changing the oblique angulation and tilting of the image intensifier.

For time efficiency and to minimize radiation, do not check AP and lateral views until all intended needle levels have been placed (trajectory view). Then, rotate to the AP and lateral views. If needed, perform minor adjustments to all needles before re-checking.

For time efficiency and to minimize radiation, do not check AP and lateral views until all intended needle levels have been placed (trajectory view). Then, rotate to the AP and lateral views. If needed, perform minor adjustments to all needles before re-checking.

Confirm the level (with the anteroposterior view).

Tilt the fluoroscope’s image intensifier cephalad or caudad.

Tilt the fluoroscope’s image intensifier cephalad or caudad.

Line up the caudad vertebral superior endplate (SEP) for the individual level being set up.

Line up the caudad vertebral superior endplate (SEP) for the individual level being set up.

Place a pillow under the patient’s abdomen, with greater posterior rotation on the ipsilateral side of needle entry, to reduce lumbar lordosis and to obtain 5 to 10 degrees of additional rotation (optional).

Place a pillow under the patient’s abdomen, with greater posterior rotation on the ipsilateral side of needle entry, to reduce lumbar lordosis and to obtain 5 to 10 degrees of additional rotation (optional).

Have patients with protuberant abdomens lie slightly obliquely so the needle entry side is slightly elevated; their abdomen may otherwise theoretically push the retroperitoneum into the needle’s trajectory.

Have patients with protuberant abdomens lie slightly obliquely so the needle entry side is slightly elevated; their abdomen may otherwise theoretically push the retroperitoneum into the needle’s trajectory.

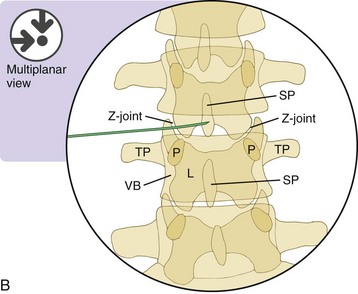

Oblique the fluoroscope’s image intensifier ipsilateral to needle entry (Figure 17–1).

Position the fluoroscope such that the superior articular process (SAP) is bisecting or nearly bisecting the SEP.

Position the fluoroscope such that the superior articular process (SAP) is bisecting or nearly bisecting the SEP.

The target needle destination is the disc immediately lateral to the junction of the inferior superior articular process and the SEP.

The target needle destination is the disc immediately lateral to the junction of the inferior superior articular process and the SEP.

Adjust the degree of angulation for each individual intervertebral disc level.

Adjust the degree of angulation for each individual intervertebral disc level.

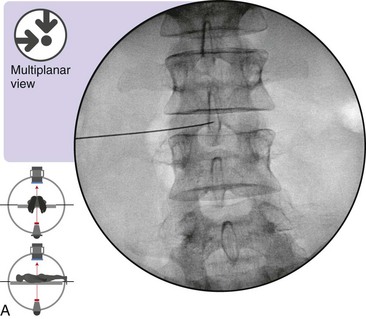

Optimal Needle Position in Multiplanar Imaging

Optimal Needle Position in Multiplanar Imaging

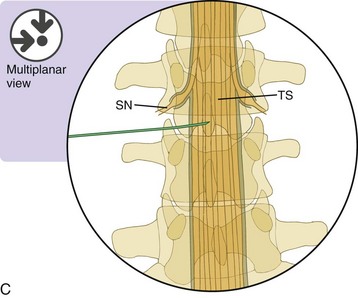

Optimal Needle Positioning in the Anteroposterior View (Figure 17–2)

The “true” anteroposterior visualization of each individual intervertebral disc is imperative (See Chapter 3 for discussion on “true” AP). The geometric center of the disc coincides with the position of the spinous process of the superior vertebral body.