Chapter 13 Lumbar spine

Conditions affecting the region

Back pain

Degenerative disease processes

Studies have shown that only a very small percentage of requests for plain radiography change patient management3 and so they are not cost-effective.4 The high radiation dose associated with lumbar spine radiography should not be used to provide patient reassurance, or indeed reassurance for the referrer.5

Metastatic disease

Metastatic disease is characterised by secondary deposits seen as lytic, and in some cases sclerotic, lesions; pathological fractures may be present. Nuclear medicine imaging or MRI are generally the most appropriate examinations for early detection.2

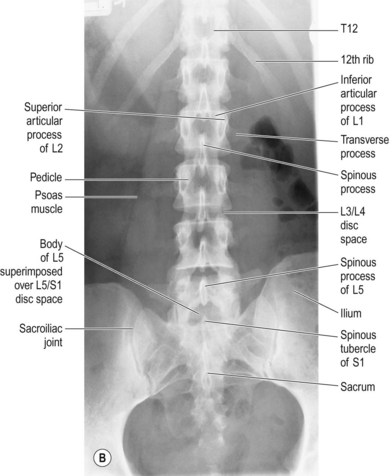

AP lumbar spine (Fig. 13.1A,B)

IR is horizontal; an antiscatter grid is employed

Positioning

• The patient is supine with their arms placed on the pillow and legs extended

• The knees may be supported with a pad for patient comfort; to reduce the lumbar lordosis and enable better visualisation of the intervertebral joint spaces, the legs should be supported with the femora at 45° or more to the table-top

• The median sagittal plane (MSP) is 90° to the table-top and the coronal plane is parallel to the table-top

• Gonad protection should be applied to all patients; if it is correctly positioned it will not obscure any relevant detail, and is essential to reduce the dose to the gonads

Collimation

Psoas muscles, transverse processes of LV1–LV5, T12/L1 joint space, sacroiliac joints

Note that this technique may be performed erect, either standing or seated; the positioning is the same but a vertical IR and antiscatter device are used.6 The central ray direction is adjusted accordingly.

Criteria for assessing image quality

• Psoas muscles, transverse processes of LV1–LV5, T12/L1 joint space, sacroiliac joints are demonstrated

• Spinous processes are in the centre of vertebral bodies, demonstrating no rotation

• L2/L3 and L3/L4 joint spaces are demonstrated; other intervertebral spaces will be projected obliquely due to lumbar curvature

• Sharp image demonstrating soft tissue of abdominal viscera in contrast to bone and air in the gastrointestinal tract; detail of bony cortex and trabeculae; spinous processes visualised through vertebral bodies

| Common errors | Possible reasons |

|---|---|

| Spinous processes not in the midline of vertebral bodies | 1. Rotation of the spine – MSP not perpendicular to the IR. Adjust the patient position so that the pelvis and shoulders are not rotated |

| 2. Scoliosis may cause this appearance and may not be improved upon. This is distinguishable from rotation due to position error by the distinct lateral curve of the column and potential variation of rotation down its length7 | |

| No intervertebral discs clearly demonstrated | Excessive lordosis – the direction of the primary beam can be adjusted so that the beam is directed through the required joint spaces (see comments below) |

It has commonly been believed that the curvature of the lumbar spine can be reduced by an angled pad being placed under the knees, enabling better visualisation of the intervertebral joint spaces by associated flattening of the lumbar lordotic curve.8 The effectiveness of knee flexion is traditionally claimed to be felt by a simple experiment: if one lies supine with the legs extended a flat hand will slide easily under the arch made by the lumbar curve. When the knees and hips are flexed, the hand feels the lumbar area press down onto its dorsal aspect, suggesting a reduction in lumbar curve. The more the hips and knees are flexed, the more the curve appears to reduce. But is the movement felt by the hand merely muscular movement rather than reduction of lordosis? Would an increase in knee/hip flexion actually show a more significant lumbar curve reduction?

The effect has been disputed by Murrie et al.,9 but this research was undertaken on a very small sample of seven examinations and this raises questions on the validity of the research. It is also noted that Murrie et al. flexed the knees over a pad, which may not offer adequate hip flexion to reduce the lumbar curve.

Further research on this topic was performed on a larger sample of 60 volunteers by Downing,10 who found that the lumbar curve was effectively reduced by up to 64%, but that in order to be effective the femora should be at 45° to the table-top, as described in the technique description. Note that the key is the angle between the femora and the table-top, not the angle of flexion of the knees.

Posteroanterior (PA) or AP?

Colleran11 showed that the magnification produced does not cause a significant reduction in image quality and indeed recommends its adoption because of the superior demonstration of the sacrum, sacroiliac joints and intervertebral joint spaces. Her work has resulted in the adoption of the PA projection in a small number of imaging departments.

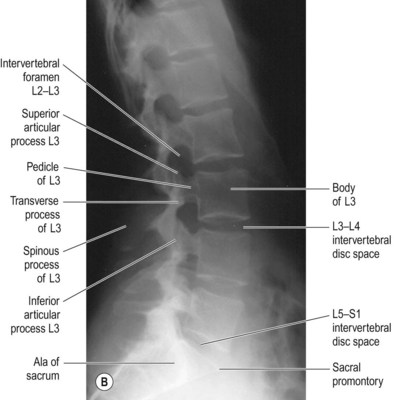

Lateral lumbar spine (Fig. 13.2A,B)

IR is usually horizontal; an antiscatter grid is employed

Erect weightbearing horizontal beam technique may be employed for this projection.6

Positioning

• From the AP position the patient is turned 90° onto their left side to bring the coronal plane 90° to the table-top and the MSP parallel to it, with their back to the radiographer for ease of positioning.

• The knees and hips are flexed for stability and comfort and the arms are rested on the pillow in front of the patient’s head; this clears the patient’s arms from the required area. A pad may be inserted between the knees to aid positioning, patient comfort and stability. Note that the choice of size is important: it should be of a size that ensures that the raised knee does not affect the parallel position of the MSP in relationship to the couch.

• A lead rubber apron is placed across the lower anterior aspect of the abdomen and pelvis for radiation protection, without obscuring the lower lumbar vertebrae and first sacral segment. A thin sheet of lead rubber may not be sufficient to absorb primary beam it impinges upon any aspect of the sheet, and should not be used.

• The spinous processes are palpated and assessed to ensure that the long axis of the spine and the MSP are parallel to the table-top; if not it will be necessary to angle the beam in a direction that will ensure the central ray strikes the long axis of the lumbar vertebrae at 90°. Very often, the female pelvis causes the spine to tilt upwards towards the pelvic end of the vertebral column, whereas the male shoulders can cause the opposite effect (although this has more effect on the lateral thoracic spine projection). Radiolucent pads, placed under the lateral aspect of the lower end of the tilted vertebral column, can be used to address this problem. However, the accuracy and effectiveness of this is in question and beam angulation is likely to be more effective (see Ch. 12 regarding the lateral thoracic spine). The alignment of the spinous processes must be assessed with the eyes level with the spine to ensure accuracy, as previously discussed. Palpation of the posterior superior iliac spines (PSISs) to check their vertical superimposition will assure accurate lateral positioning of the pelvic end of the lumbar vertebrae. The shoulder end of the column should also be assessed so that the posterior aspect of the patient’s shoulders is vertical.

• If the spine has a lateral curvature when the patient is lying on their side, with L1 and L5 higher than the middle vertebrae, it is not usually necessary to make adjustments in the central ray or to use pads. This is because the oblique rays around the central ray are likely to correspond with the obliquity of the intervertebral joint spaces. If a slight curvature appears with L1 and L5 lower than the middle vertebrae (not commonly encountered), it will be more advantageous to turn the patient onto their opposite side for this projection. In any case, lateral curvature is often best assessed by viewing the AP projection before attempting the lateral position.

• If the patient has scoliosis, it is recommended that the side to which the largest curvature is more prominently demonstrated is placed nearest the X-ray couch. The central ray is then directed towards the lowest point of the convex shape of the curvature. This ensures that the oblique rays that penetrate each of the vertebral bodies produce an image which assists in reducing the superimposition of the vertebral bodies over intervertebral joint spaces, demonstrating the joint spaces as efficiently as is possible under the circumstances.

• A sheet of lead rubber is placed on the table-top behind the patient to prevent scatter reaching the receptor, thereby improving image quality. There has been some discussion as to the efficacy of lead rubber in this circumstance,12 but its use has been shown to be effective and should be mandatory.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree