Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

- ◼

Complex drainage system of lymphatic capillaries connected by ducts connected to central lymph node ‘stations’ following a similar course to the arterial system ( Figs. 21.1 and 21.2 ).

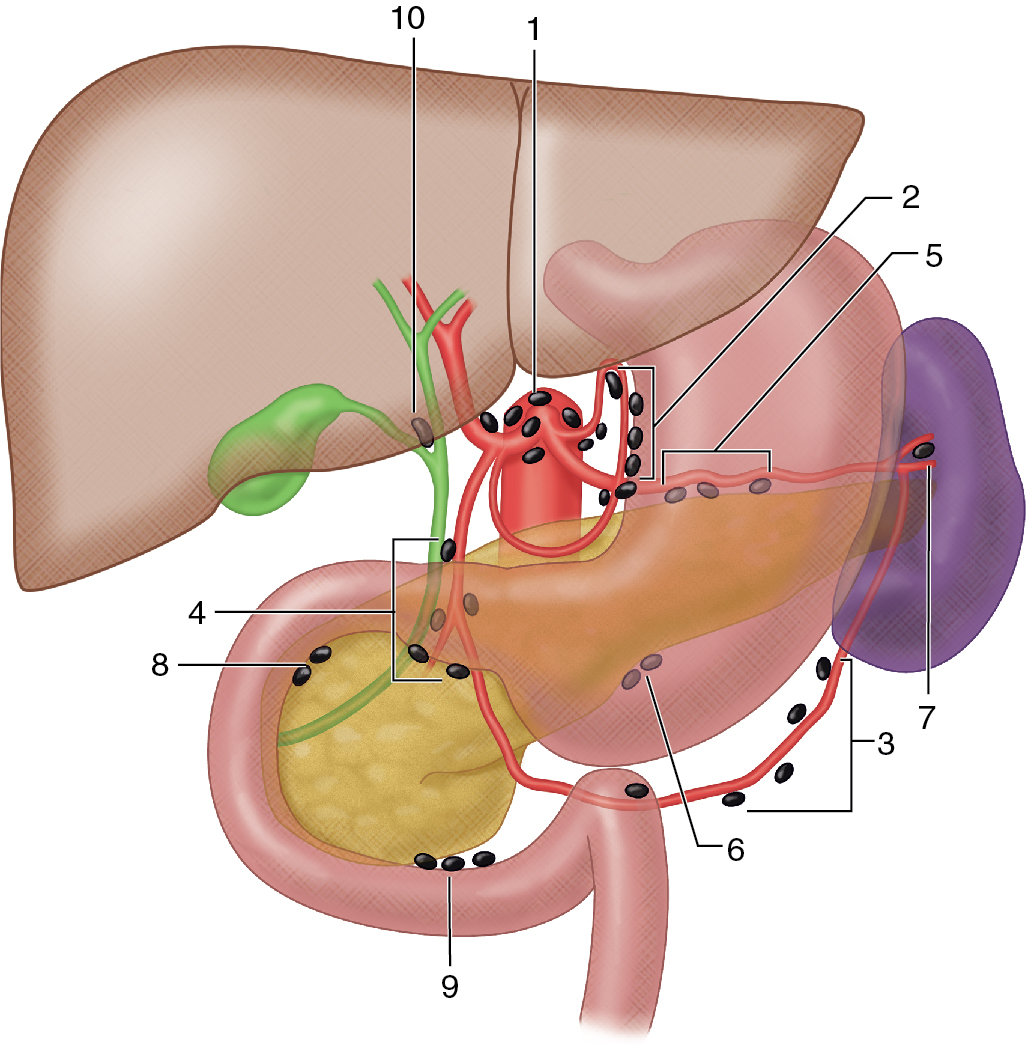

Fig. 21.1

Illustration of the upper gastrointestinal tract depicting the lymph nodes of the stomach, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen: 1, celiac; 2, gastric (right and left); 3, gastroepiploic (right and left); 4, pyloric; 5, superior pancreatic; 6, inferior pancreatic; 7, perisplenic; 8, superior pancreaticoduodenal; 9, inferior pancreaticoduodenal; 10, cystic.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging, ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

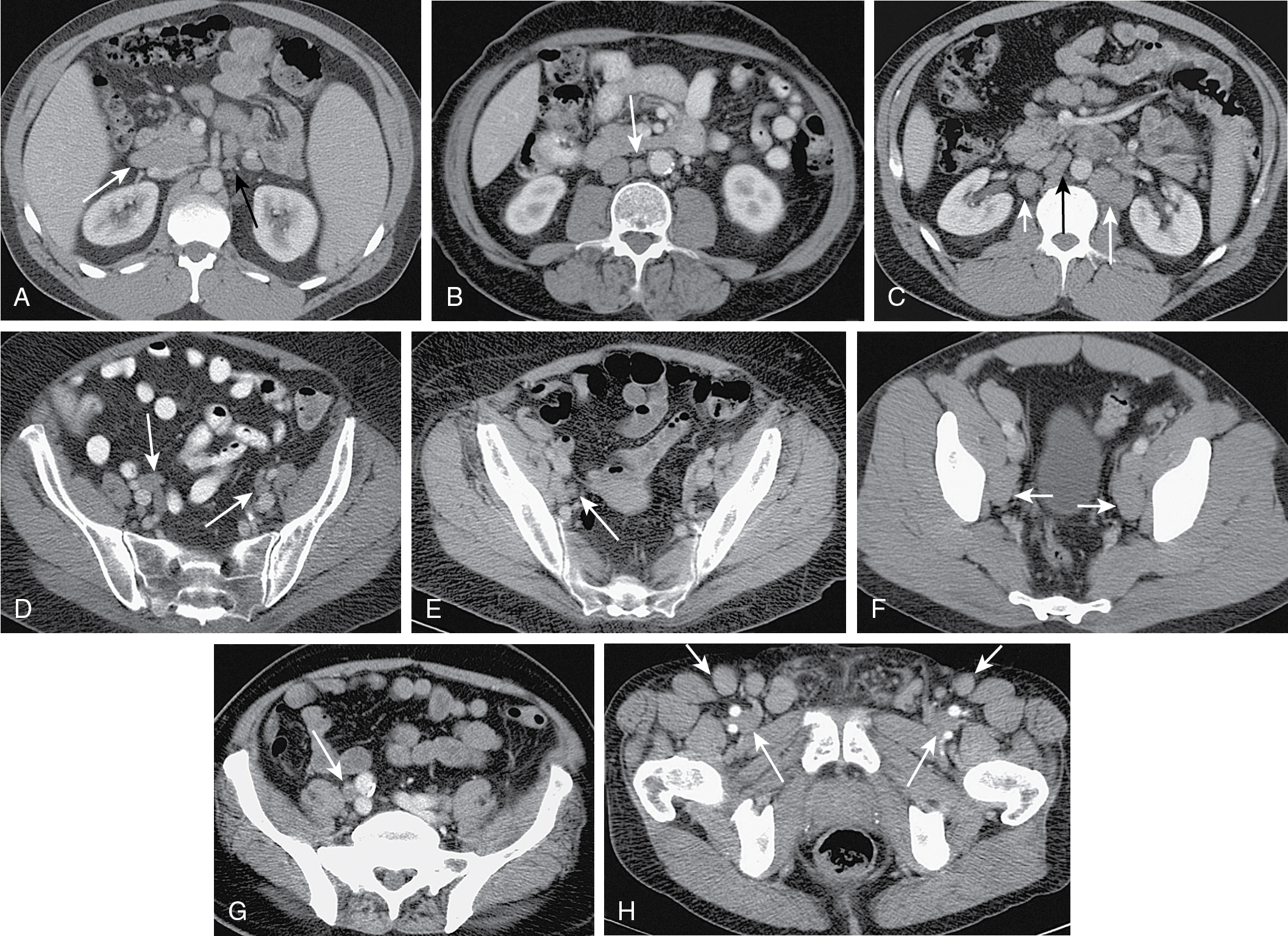

Fig. 21.2

Representative axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) images of the abdomen and pelvis at various levels demonstrating the normal location of the abdominal lymph nodes. A, Portocaval ( white arrow ); Superior mesenteric artery ( black arrow ). B, Aortocaval ( arrow ). C, Paracaval ( short white arrow ), aortocaval ( black arrow ), paraaortic ( long white arrow ). D, Right and left iliac bifurcation ( arrows ). E, Right external iliac ( arrow ). F, Right and left obturator ( arrows ). G, Right common iliac ( arrow ). H, Superficial inguinal ( short arrows ), deep inguinal ( long arrows ).

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging, ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

Lymph nodes play an integral part in the immune system through both physical and immunological elimination of bacteria, neoplastic cells, and other foreign substances.

- ◼

Approximately 230 to 250 lymph nodes within the abdomen (500–700 whole body); generally divided into abdominal and retroperitoneal compartments; visceral (organs) and parietal (skin, muscles, fascia, etc.).

Techniques

- ◼

Primary evaluation of abdominal lymph nodes performed through computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET)/CT. Role of lymphangiography is limited mostly to interventional procedures.

- ◼

Venous phase CT postintravenous contrast preferred to assess enhancement patterns, differentiate smaller nodes from bowel/vessels, as well as concurrent evaluation of visceral organs. Pelvic lymph node abnormalities commonly undetected on unenhanced CT.

Computed tomography

- ◼

Normal lymph nodes are ovoid (kidney) shaped with attenuation similar to soft tissue (40–60 HU) with mild to moderate contrast enhancement ( Fig. 21.3 ).

Fig. 21.3

Axial contrast-enhanced image at the level of the pelvis highlighting the computed tomography appearance of normal lymph nodes ( arrows ). The inguinal lymph nodes seen in the image are well circumscribed and oval, with homogeneous soft tissue attenuation. The presence of a distinct fatty hilum, a distinguishing feature of benign lymph nodes, is well depicted in the superficial inguinal node.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging, ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

Normal size 5 to 15 mm measured in either short- or long-axis dimension based on lymph node station; size criteria for enlargement dependent on anatomic location ( Fig. 21.4 ).

Fig. 21.4

Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography image showing the correct method of estimating nodal size. The nodal size is obtained by measuring the maximum short-axis diameter (shown here with a check mark ).

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

Common mimics of adenopathy include: enlarged pelvic veins/varices, accessory splenic or ovarian tissue, unopacified bowel loops/gastric diverticula.

- ◼

Size is only widely accepted criterion for diagnosis because abnormalities in normal size nodes cannot be reliably detected. These include abnormal shape, irregular margins, variable attenuation, and abnormal enhancement.

- ◼

CT is unable to reliably differentiate between reactive hyperplasia and metastases.

Ultrasound

- ◼

Limited role of transabdominal US secondary to anatomic location of nodes with the abdomen. Endoscopic ultrasound is being increasingly used for assessment of disease spread in gastrointestinal (GI) and pancreaticobiliary malignancies.

- ◼

More detailed evaluation of morphology can be achieved with focused ultrasound, which can aid in diagnosing pathology in normal sized lymph nodes.

- ◼

Isoechoic to hyperechoic with a distinct fatty hilum seen in benign nodes.

- ◼

Enlargement, rounded/lobulated shape, hypoechogenicity, sharp/distinct borders are suggestive of disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

Increasingly used for diagnosing abdominopelvic malignancies; especially helpful in intrapelvic disease given high soft tissue contrast (rectum, bladder, cervix, etc.).

- ◼

Can help differentiate normal size nodes versus normal size nodes with metastatic disease.

- ◼

Primary sequences are T1, T2, T1 postgadolinium sequences with fat suppression, and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI).

- ◼

Normal MR features: round/ovoid shape ( Fig. 21.5 ).

- ◼

T1: lower signal than fat, higher than muscle.

- ◼

T2: closer signal to fat, higher than muscle.

- ◼

Increased T2 signal compared with T1 can confirm node identity.

- ◼

Homogeneous enhancement.

Fig. 21.5

T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) magnetic resonance images showing a right superficial inguinal lymph node ( arrows ). The node is hypointense to fat and isointense to muscle on the T1W image, whereas on the T2W image, it becomes isointense to fat and hyperintense to muscle.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging, ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

- ◼

- ◼

Like CT, abnormality is widely based on accepted criteria for size.

- ◼

Changes in the normal signal intensity of nodes can also be used ( Fig. 21.6 ):

- ◼

Malignant nodes can have heterogeneous T2 signal.

- ◼

Necrosis in metastatic disease: decreased T1, increased T2 signal.

- ◼

Residual disease posttreatment: fibrosis (low T2) versus residual disease (high T2).

- ◼

However, even disease free treated nodes can be positive for up to 1 year; infection/inflammation could mimic residual disease.

- ◼

- ◼

Restricted diffusion (+DWI) is seen in malignancy but also in normal lymph nodes because of their hypercellular composition.

- ◼

Rapid enhancement or peripheral rim enhancement suggest malignancy.

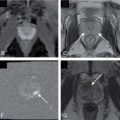

Fig. 21.6

54-year-old woman with metastatic cervical carcinoma. T1-weighted (A), T2-weighted (B), and diffusion weighted (C) images show two enlarged metastatic left pelvic sidewall lymph nodes ( arrows ). The metastatic nodes are bright and are more conspicuous on the diffusion-weighted image.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

Positron emission tomography

- ◼

Increased metabolic activity by tumor cells causes increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake, which can be compared with normal background activity in assessment of metastatic disease, primary lymphoma, and monitoring of treatment response/disease recurrence ( Fig. 21.7 ).

Fig. 21.7

21-year-old man with paraaortic lymph node involvement in a T-cell–rich, B-cell lymphoma (non-Hodgkin). A, Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) image shows a mildly enhancing left paraaortic lymph node ( arrow ) with perinodal fatty stranding. However, the CT features do not allow reliable differentiation between a reactive inactive node and active lymphomatous involvement. B, Axial fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) image shows an area of intense FDG uptake ( arrow ) in the retroperitoneum. Because of the absence of appropriate anatomic landmarks on this image, the area of high FDG uptake cannot be confidently attributed to lymphomatous spread. C, Axial PET/CT image demonstrates that the abnormal FDG uptake ( arrow ) corresponds to the left paraaortic lymph node in A, confirming the presence of nodal metastases.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging, ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

- ◼

Extremely sensitive and specific for detection of metastatic disease, especially in normal size lymph nodes. Can detect disease before macroscopic changes in lymph node architecture.

- ◼

FDG is not a cancer specific agent; increased uptake with sarcoidosis, tuberculosis (TB), infection, abscess.

Specific disease processes

Benign lymph node diseases of the abdomen and pelvis

Infection

- ◼

Common

- ◼

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency virus (AIDS): adenopathy is most common abdominal finding.

- ◼

Can be infectious (TB, mycobacterium avium complex [MAC], histoplasmosis) or neoplastic (non-Hodgkin lymphoma [NHL], Kaposi).

- ◼

- ◼

Computed tomography

- ◼

Central low density or necrosis within nodes; TB (93%), MAC (14%).

- ◼

TB: disease in retroperitoneum (RP), mesentery, splenic hilum; complicated by peritonitis and implants.

- ◼

Kaposi: hyperattenuating nodes in RP, mesentery, groin. 85% of hyperattenuating nodes in HIV.

- ◼

AIDS-related lymphoma: bulky disease (>3 cm) with soft tissue attenuation.

- ◼

TB: around 15% of cases with extrapulmonary TB, about half of those with abdominal TB have only nodal disease. Rarely greater than 4 cm.

- ◼

Route of spread determines location; lower paraaortic (hematogenous), upper abdomen (either blood or direct).

- ◼

Form multilocular nodal conglomerates from diseased adjacent nodes.

- ◼

Computed tomography

- ◼

Central hypodensity (caseation/necrosis) with peripheral enhancement (granulation) ( Fig. 21.8 ).