HD is characterized histologically by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells. Four histologic types of HD are recognized in the Rye classification: nodular sclerosis (accounting for 50% to 80% of adult HD cases); lymphocyte predominance; mixed cellularity; and lymphocyte depletion.

HD has a predilection for thoracic involvement. Up to 85% of patients with HD have thoracic involvement at the time of diagnosis; nearly all of them have mediastinal lymph node enlargement.

Lymph Node Involvement

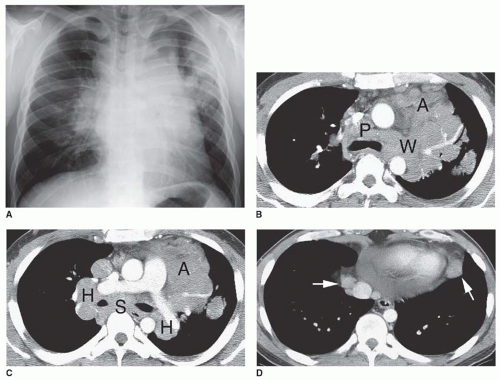

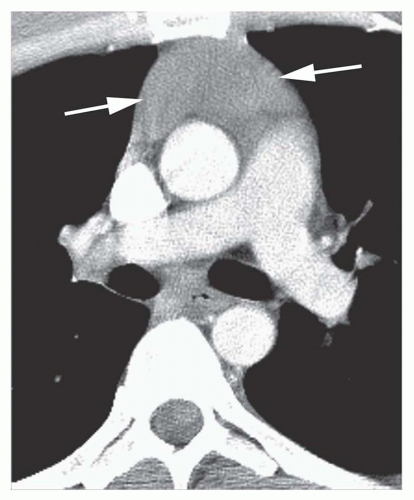

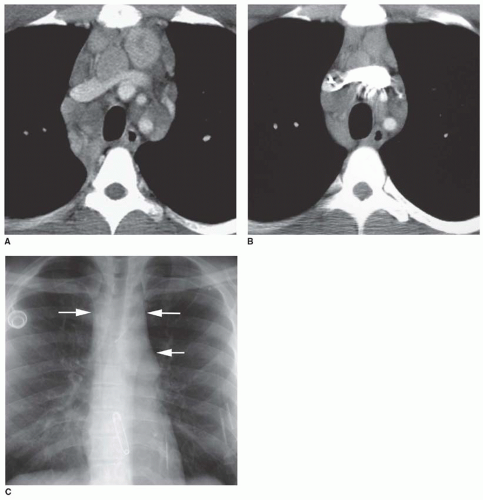

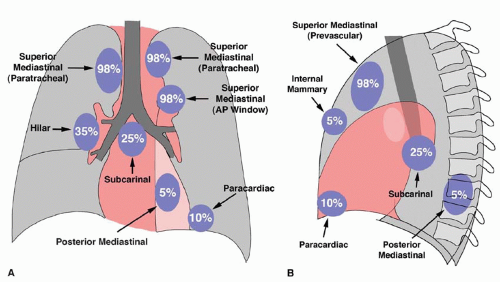

HD most often involves superior mediastinal (i.e., prevascular, paratracheal, and aortopulmonary) lymph nodes. These node groups are abnormal in as many as 85% of patients with HD and 98% of those with thoracic involvement (

Figs. 5-1 and

5-2); if these nodes appear normal on computed tomography (CT), intrathoracic adenopathy is unlikely to represent HD.

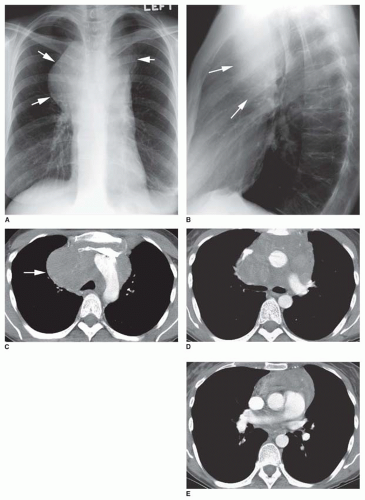

Other sites of involvement in patients with thoracic disease are as follows: the hilar nodes, in about 35% of patients; the subcarinal nodes, in about 25%; the paracardiac (cardiophrenic angle) lymph nodes, in 10%; the internal mammary nodes, in 5%; and the posterior mediastinal (i.e., paravertebral, paraaortic, and retrocrural) nodes, in 5% (see

Figs. 5-2 and

5-3).

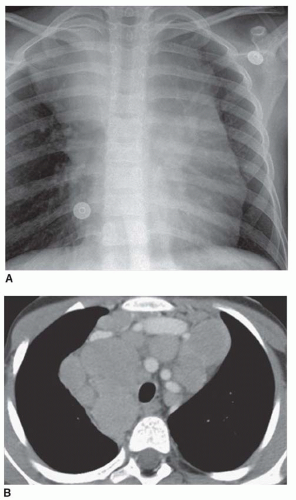

Multiple node groups are involved in 85% of those HD patients who have thoracic node involvement. Enlargement of a single node group can be seen in some patients with HD, but it is uncommon, occurring in only 15% of cases with node involvement. Anterior (prevascular) lymph nodes are most often involved as a single group (

Fig. 5-4), and this appearance usually indicates the presence of nodular sclerosing HD.

On plain radiographs, anterior mediastinal lymph node enlargement may result in a unilateral or bilateral mediastinal abnormality (see

Figs. 5-1A and

5-3A). Enlargement of paratracheal or aortopulmonary window nodes often results in a unilateral or asymmetrical abnormality. Because

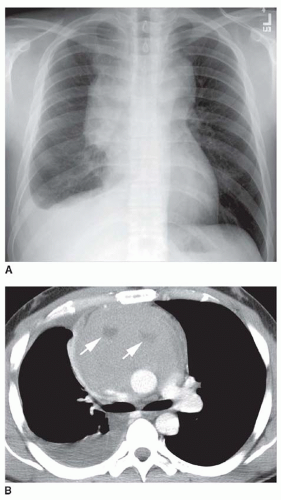

multiple lymph nodes are involved, mediastinal masses in HD often appear elongated or lobulated in contour. Roughly spherical masses also can be seen (

Fig. 5-5). Poor definition of the mass can indicate invasion or extension into adjacent lung.

CT is advantageous in showing abnormalities of mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with HD. Although it is uncommon for CT to show evidence of mediastinal adenopathy if the chest radiograph is normal, in cases in which the radiograph shows lymph node enlargement, CT detects additional sites of adenopathy in many patients. Findings shown only on CT may change the treatment plan in as many as 10% of patients. CT is most helpful in diagnosing subcarinal, internal mammary, and aortopulmonary window node enlargement that is not visible on radiographs.

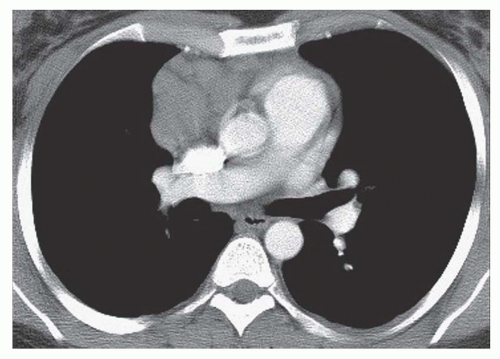

On CT, abnormal lymph nodes may appear welldefined and discrete (

Fig. 5-6), may appear matted (with

intervening fat planes poorly seen; see

Fig. 5-3B and C), or may be associated with diffuse mediastinal infiltration (with individual lymph nodes being invisible; see

Fig. 5-5C and D). Most often, enlarged lymph nodes are of homogeneous soft tissue attenuation, but in 10% to 20% of cases, lymph node masses show areas of low attenuation or necrosis following contrast enhancement (

Fig. 5-7). Inhomogeneity without obvious necrosis also may be seen (see

Fig. 5-5D). Invasion of mediastinal structures such as the superior vena cava, esophagus, or airways may occur.

Rarely, untreated patients show fine, stippled lymph node calcification. Lymph node calcification is much more common following treatment, with a stippled, confluent, or, less often, “egg-shell” appearance (

Fig. 5-8). Calcification usually occurs after radiation; calcification after chemotherapy is less common.

HD also has a predilection for involvement of the thymus in association with mediastinal lymph node enlargement. Thymic enlargement is seen in 30% to 40% of cases, but may be difficult to distinguish from an anterior mediastinal lymph node mass unless the normal thymic shape is preserved (see

Figs. 5-5E and

5-9). In the presence of thymic involvement, a visible mediastinal mass can project to both sides of the mediastinum.

HD is believed to be unifocal in origin, spreading to involve contiguous lymph nodes. It is unusual for HD to skip lymph node groups, and if nodes contiguous with the mediastinum, such as the lower neck or upper abdomen, are not involved by HD, it usually is not necessary to scan more distant regions, such as the pelvis.

However, in patients with mediastinal HD, scanning always should be extended to include the upper abdomen. Intra-abdominal paraaortic adenopathy can be found in 25% of patients with HD, and the spleen and liver are involved in 35% and 10% of patients, respectively.

The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of lymph node masses in HD varies with the histology. In nodular sclerosing HD, large amounts of fibrous tissue typically are interlaced with malignant cells. Patients typically show a heterogeneous pattern with mixed high and low signal intensities on T2-weighted images. Low signal intensity areas on T2-weighted images are related to regions of fibrosis in the tumor, and high-intensity regions represent tumor tissue or cystic regions. HD also may demonstrate homogeneous high signal intensity similar to that of fat on T2-weighted images.

Lung Involvement

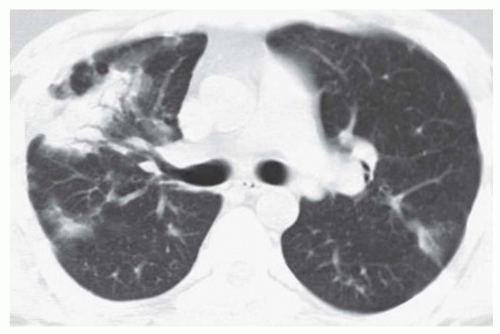

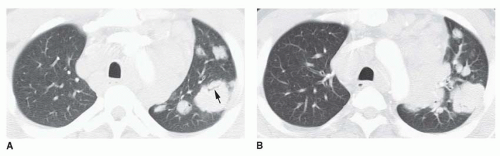

Lung involvement by HD is seen in 10% of patients at the time of presentation. It is almost always associated with mediastinal (and usually ipsilateral hilar) adenopathy (

Fig. 5-10). A variety of manifestations of lung involvement may be seen, but the most common are (a) direct invasion of lung contiguous with abnormal nodes and (b) isolated single or multiple lung nodules, masses, or areas of consolidation. Direct invasion and the presence of nodules or masses occur with about equal frequency.

Direct extension from hilar or mediastinal nodes results in coarse linear or streaky opacities radiating outward into the lung, corresponding on CT to thickening of the peribronchovascular interstitium. Interlobular septal thickening may be associated. In some patients, the appearance may mimic that of lymphangitic spread of carcinoma.

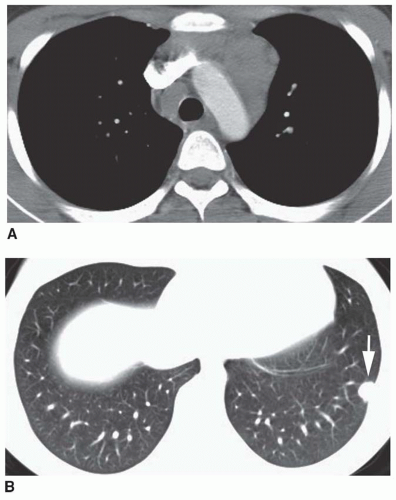

Discrete, single or multiple, well-defined or ill-defined, large or small lung nodules or mass-like lesions, or localized areas of air-space consolidation associated with air bronchograms may be seen (

Figs. 5-10 and

5-11). These can cavitate, with thick or thin walls. Peripheral, subpleural masses are relatively common (

Fig. 5-12).

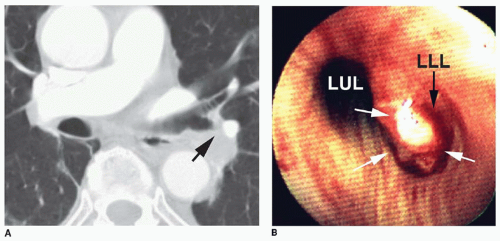

HD occasionally involves bronchi with endobronchial masses or bronchial compression associated with atelectasis (

Fig. 5-13).

In previously untreated patients, lung disease is uncommon in the absence of radiographically demonstrable lymph node enlargement; however, lung recurrence can be seen without node enlargement in patients with prior mediastinal radiation (see

Fig. 5-11).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access