Metastatic Tumor

W. Richard Webb

Thoracic structures commonly are involved in patients with metastatic neoplasm, and the chest is often the first site in which metastases are detected.

MECHANISMS OF SPREAD

Metastatic tumor may involve thoracic structures in several ways.

Direct extension from the primary tumor with secondary involvement of the lung, pleura, or mediastinal structures. This mode of spread is most common with thyroid tumors, esophageal carcinoma, thymoma and thymic malignancies, lymphoma, and malignant germ cell tumors.

Hematogenous spread of tumor emboli to pulmonary or bronchial arteries. This usually results in the presence of lung nodules and is most common with primary tumors that have a good vascular supply.

Lymphatic spread to involve the lung, pleura, or mediastinal lymph nodes. The lung may be diffusely involved by tumor following lymphatic or lymphangitic spread of cells from hematogenous metastases, hilar lymph node metastases, or upper abdominal tumors. Lymphatic spread of extrathoracic tumors to mediastinal lymph nodes also may occur via the thoracic duct, with retrograde involvement of hilar lymph nodes and the lung parenchyma. Tumors that commonly metastasize in this fashion include carcinomas of the breast, stomach, pancreas, prostate, cervix, and thyroid.

Spread within the pleural space due to pleural invasion from a local tumor (e.g., thymoma) or lung carcinoma.

Endobronchial spread of cells from an airway tumor. This mechanism of metastasis is uncommon. It is most common in patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (Fig. 4-1) but may be seen with other cell types of lung cancer (Fig. 4-2). It is also thought to occur in patients with tracheobronchial papillomatosis (see Figs. 3-55 and 3-56 in Chapter 3).

MANIFESTATIONS OF METASTASTIC TUMOR

Lung Nodules

Lung nodules are the most common thoracic manifestation of metastasis. In most cases they are hematogenous in origin (Table 4-1). They tend to predominate in the lung bases, which receive more blood flow than the upper lobes.

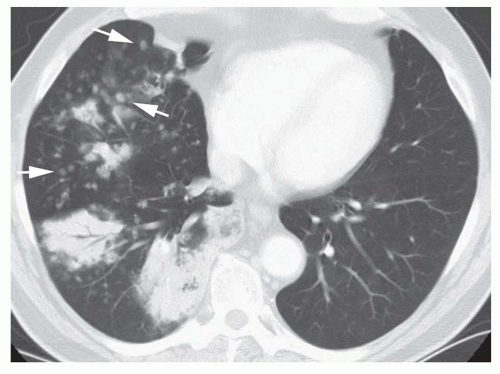

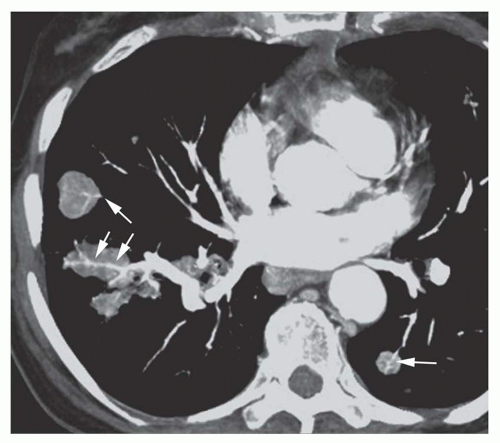

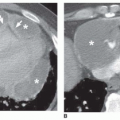

Nodules tend to be sharply marginated in most cases and round or lobulated in contour (Fig. 4-3). Poorly marginated nodules may be seen in the presence of surrounding hemorrhage or local invasion of the adjacent lung (Fig. 4-4). In some cases, individual metastases are seen to have a relationship to small vascular branches, suggesting a hematogenous origin. This is termed the “feeding vessel” sign (Fig. 4-5). Nodules may be small or large. Using computed tomography (CT), metastasis as small as 1 to 2 mm may be visible.

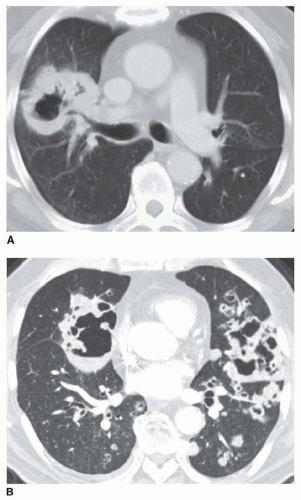

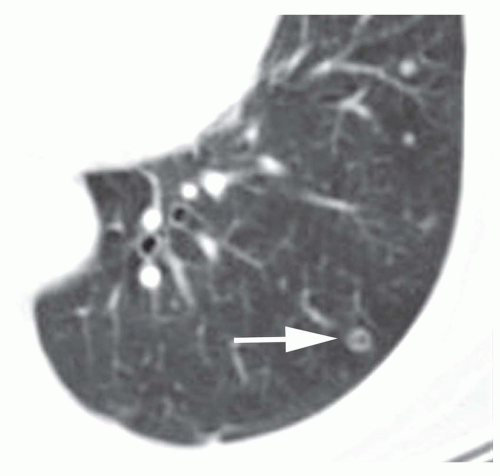

Cavitation of metastases is not as common as with primary lung carcinoma, but it occurs in about 5% of cases. It may be seen even with small nodules (Fig. 4-6). The likelihood of cavitation varies with histology. Cavitation is most common with squamous cell tumors and transitional cell tumors, but also may be seen in adenocarcinomas, particularly from the colon, and in some sarcomas.

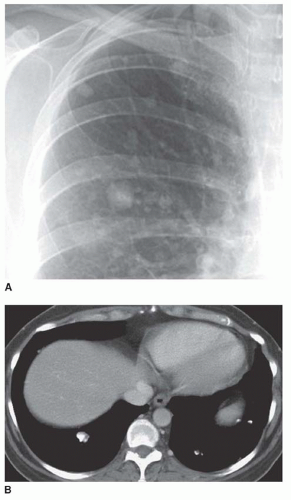

Calcification of metastases occurs most commonly with osteogenic sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, thyroid carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma

(Fig. 4-7). Calcification may be dense, particularly with osteogenic sarcoma, mimicking a granuloma. Calcification may persist following successful chemotherapy despite resolution of the tumor.

(Fig. 4-7). Calcification may be dense, particularly with osteogenic sarcoma, mimicking a granuloma. Calcification may persist following successful chemotherapy despite resolution of the tumor.

CT is considerably more sensitive than plain radiographs in detecting lung nodules in patients with metastatic tumor, although the sensitivity of CT varies with slice thickness. The sensitivity of chest radiographs for detecting nodules in patients with lung metastases is about 40% to 45%, although this varies with the size of the nodules. Using spiral CT with 5-mm collimation, a sensitivity of more than 80% has been reported for detection of nodular metatases 5 mm or less in diameter; the sensitivity of CT in detecting metastases larger than 5 mm is 100%.

TABLE 4.1 Nodular Metastases | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

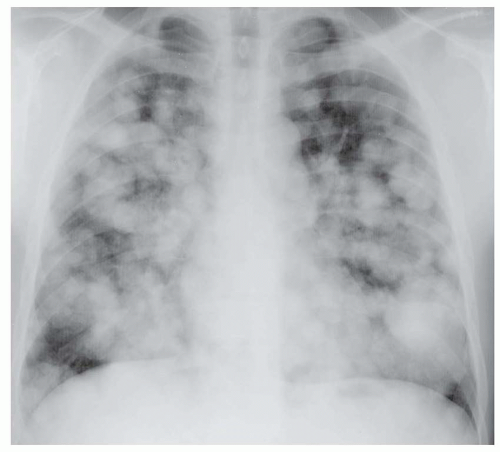

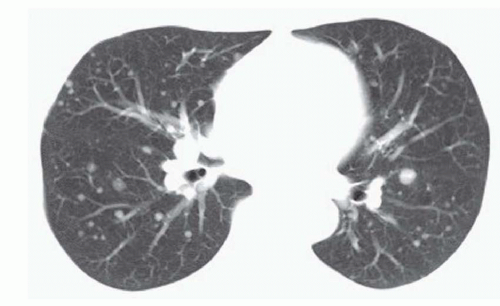

FIG. 4.3. Metastatic salivary gland carcinoma with rounded and lobulated metastases. Nodules vary in size; this is typical with metastatic tumor and is less common with benign diseases. |

On the other hand, lung nodules seen on CT in patients with a known tumor often represent something other than metastases. Granulomas, focal areas of infection, scarring, and intrapulmonary lymph nodes are all very common, and mimic metastases on CT. These are generally small, measuring a few mm in diameter. Nodules larger than a few mm, particularly when rounded and sharply defined, are more likely to represent metastatic tumor. If small nodules are seen on CT in a patient with a known tumor, obtaining a follow-up CT at 6 weeks to 3 months is appropriate. Nodules representing metastases typically show growth; benign nodules usually show no growth, decrease in size, or resolve.

Multiple Nodule

Nodular metastases usually are multiple. The nodules often vary in size, representing multiple episodes of tumor embolization or different growth rates (see Figs. 4-3, 4-4, and 4-8);

this appearance is less common with benign nodular disease, such as sarcoidosis. Occasionally, all of the nodular metastases are of the same size. When there are numerous nodules, they tend to be distributed throughout the lung (Fig. 4-9). When the metastases are few in number, they may be predominantly subpleural (see Fig. 4-4B).

this appearance is less common with benign nodular disease, such as sarcoidosis. Occasionally, all of the nodular metastases are of the same size. When there are numerous nodules, they tend to be distributed throughout the lung (Fig. 4-9). When the metastases are few in number, they may be predominantly subpleural (see Fig. 4-4B).

FIG. 4.6. Cavitary nodule in metastatic transitional cell carcinoma. Even though the nodule is very small (arrow), a distinct cavity is visible. |

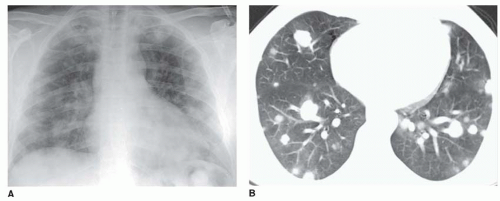

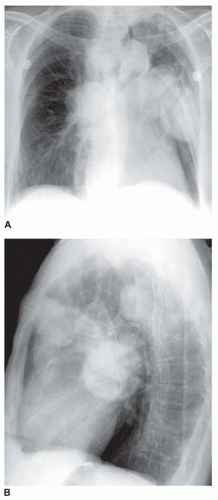

FIG. 4.7. Ossified metastases secondary to osteogenic carcinoma. A: Chest radiograph shows dense nodules. B: CT shows dense calcification, which is typical of this tumor. |

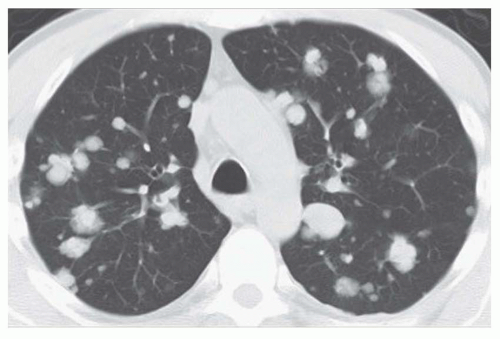

On CT, numerous nodules tend to involve the lung in a diffuse fashion without regard for specific anatomic structures, a distribution termed “random” (see Figs. 4-3 and 4-9B). This pattern is described in detail in Chapter 10.

The size and number of nodules vary greatly. Nodules may be small (i.e., miliary) and very numerous (Fig. 4-10); this appearance often is seen with very vascular tumors (e.g., thyroid carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, sarcomas) and presumably reflects a single massive shower of tumor emboli. Fewer, larger metastases also may be seen; when these are well defined, they are referred to as “cannonball metastases” (see Figs. 4-8 and 4-11). This type of metastasis is seen most commonly with tumors of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract.

Most patients (80% to 90%) with multiple metastases have a history of neoplasm. In some patients, however, there is no history of a primary tumor at the time of diagnosis; in others, the primary tumor may never be found.

Solitary Nodule

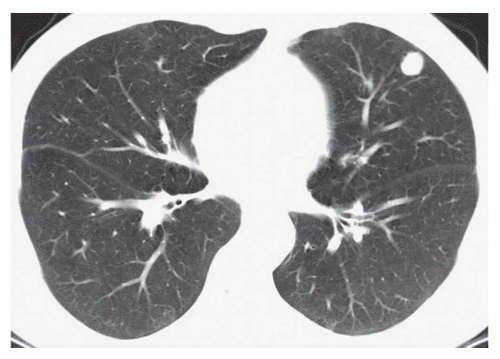

A metastatic tumor occasionally presents as a solitary nodule (Fig. 4-12). About 5% to 10% of solitary nodules represent solitary metastases. Solitary metastases are most common with carcinomas of the colon, kidney, and testis, and with sarcomas and melanoma. It must be emphasized that many patients who appear to have a solitary metastasis visible on chest radiograph are discovered to have multiple pulmonary nodules on CT, with one nodule being dominant.

A solitary metastasis is more likely to have a smooth margin than is primary lung carcinoma (see Fig. 4-12), but this finding on its own is not sufficient to permit a reliable distinction between primary and metastatic tumors. Solitary metastases may appear spiculated, and primary carcinomas may be smooth. A solitary metastasis is more likely when the tumor is located at the lung base; primary carcinoma is more common in the upper lobes.

FIG. 4.10. Metastatic thyroid carcinoma. Numerous small metastases are visible, distributed throughout the lung. |

FIG. 4.11. Cannonball metastases in metastatic vaginal carcinoma. Frontal (A) and lateral (B) radiographs show several large, well-defined metastases. |

FIG. 4.12. Solitary metastasis shown on CT at the lung base. No other nodules were visible. This nodule is sharply marginated. Biopsy showed the same cell type as the primary tumor. |

In a patient with a known extrathoracic tumor and a solitary nodule detected radiographically, the likelihood that the nodule is a metastasis (as opposed to primary lung cancer) varies with the cell type of the primary tumor. Patients with carcinomas of the head and neck, bladder, breast, cervix, bile ducts, esophagus, ovary, prostate, or stomach are more likely to have primary lung carcinoma than lung metastasis (ratio, 8:1 for patients with head and neck cancers; 3:1 for patients with other types of cancer). Patients with carcinomas of the salivary glands, adrenal gland, colon, parotid gland, kidney, thyroid gland, thymus, or uterus have fairly even odds (ratio, 1:1). Patients with melanoma, sarcoma, or testicular carcinoma are more likely to have a solitary metastasis than a lung carcinoma (ratio, 2.5:1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree