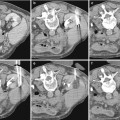

Fig. 1

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a 76-year-old man. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT in the corticomedullary phase shows multiple hypovascular masses in both kidneys (black arrows). (b) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a T2-hypointense mass in the upper pole of the left kidney. (c) Diffusion-weighted imaging of this lesion obtained on a b-value of 1000 shows high signal

On MRI, the masses are hypointense on T1-weighted images and iso- or hypointense on T2-weighted images. The characteristics on contrast-enhanced MRI are similar to CT (Sheth et al. 2006).

Large retroperitoneal lymph adenopathies are present in less than 50 % of the cases (Urban and Fishman 2000) and are the key feature for the diagnosis of lymphoma.

In the absence of large retroperitoneal adenopathies, differential diagnosis of bilateral multiple renal lymphoma includes renal metastases and papillary renal cell carcinoma. Clinical history is crucial in the diagnosis, but if there is no known primary malignancy present, biopsy needs to be performed to differentiate between surgical disease and disease processes where surgery must be avoided (Sheth et al. 2006).

From a theoretical point of view, other differential diagnoses include acute pyelonephritis, septic emboli, renal infarcts, and abscesses (Sheth et al. 2006). Their specific radiologic appearance and clinical presentation usually enable the differentiation with lymphoma.

1.3.2 Retroperitoneal Extension

Renal invasion from retroperitoneal extension is the second most frequent presentation pattern and accounts for 25–30 % of the cases (Cohan et al. 1990).

Large confluent retroperitoneal masses encase the renal vasculature and invade the renal hilum with occasionally mild secondary hydronephrosis (Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006; Leite et al. 2007; Symeonidou et al. 2008) (Fig. 2).

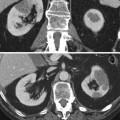

Fig. 2

Follicular lymphoma in a 71-year-old man. Contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows a large hypovascular retroperitoneal mass extending into the renal hilum with encasement of the left renal vessels (arrow) and involving the kidney resulting in a hypoattenuating enlarged left kidney. Hydronephrosis is absent

Occlusion or thrombosis of renal veins and arteries is rare despite the, at times, massive tumor burden (Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006). Lateral displacement of the kidney is not infrequent.

Bulky lymphadenopathies can be seen in other tumors, even with extension into the kidney. Differential diagnosis is based on the aspect of the adenopathies, which tend to be softer in lymphoma. Lymphoma adenopathies encase vascular structures, whereas adenopathies from other primaries obstruct and invade vascular structures (Urban and Fishman 2000).

1.3.3 Infiltrative Disease

Infiltrative renal involvement presents as nephromegaly with disruption of the internal architecture and preservation of renal shape (Fig. 3). It occurs generally bilateral and is more commonly seen in Burkitt lymphoma (Sheth et al. 2006). It is observed in 20 % of patients with renal lymphoma (Reznek et al. 1990).

Fig. 3

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (immunomodulator agent-related lymphoproliferative disorder) in a 75-year-old woman. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows an infiltrative hypovascular mass in the upper pole of the left kidney with discrete infiltration of the perirenal fat (arrow). (b) Coronal image shows diffuse pericardial involvement (arrow)

Intravenous contrast administration is essential to appreciate the enhancement characteristics, the focal ill-defined hypovascular areas, and the loss of corticomedullary differentiation secondary to the infiltrative growth pattern. Encasement of the renal collecting system is often present.

Renal function is frequently moderately impaired.

Certainly, when this presentation is unilateral, the differential diagnosis includes other tumoral disease processes (renal cell carcinoma, medullary tumors, transitional and squamous cell carcinoma, renal sarcoma, leukemia, plasmocytoma, metastases, and infiltrative pediatric tumors) and inflammatory diseases (bacterial and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, renal parenchymal malacoplakia) with a predominately infiltrative pattern (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

1.3.4 Solitary Mass

A solitary mass is found in 10–20 % of the cases (Cohan et al. 1990; Reznek et al. 1990). Solitary masses exhibit similar imaging characteristics as the multiple masses (Fig. 4). Solitary masses can be as large as 15 cm (Reznek et al. 1990).

Fig. 4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a 69-year-old man. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows a solitary hypodense mass in the upper pole of the right kidney. (b) Fusion FDG-PET-CT shows the increased FDG uptake in the lesion

Differential diagnosis with other solitary renal masses such as renal carcinoma has to be included, yet, the majority of renal cell carcinomas show hypervascular and heterogeneous enhancement. The presence of vascular invasion is also almost exclusively seen in renal cell carcinoma. Retroperitoneal adenopathy can be present in both cases, but tend to be much larger and confluent in lymphoma (Urban and Fishman 2000).

1.3.5 Perirenal Disease

Perirenal involvement is usually a part of retroperitoneal extension.

Isolated perirenal disease is very unusual (<10 % of cases of perirenal lymphoma) and appears as a soft tissue mass involving the perirenal space partially or completely and compresses but not invades the kidney (Bechtold et al. 1996; Leite et al. 2007; Surabhi et al. 2008) (Fig. 5). The presentation of perirenal soft tissue mass without renal invasion and functional impairment is almost pathognomonic (Sheeran and Sussman 1998; Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006). To differentiate the perirenal soft tissue mass from the underlying parenchyma, contrast administration is crucial.

Fig. 5

Monocytoid B-cell lymphoma in an 80-year-old man. Contrast-enhanced CT in the parenchymal phase shows besides renal involvement (black arrow) the presence of an isodense to slightly hypodense mass in the perirenal space, posterior to the inferior pole of the right kidney (white arrow)

Findings can yet be more limited to plaques and nodules in the perirenal space and thickening of Gerota’s fascia (Sheeran and Sussman 1998). These limited findings can cause a diagnostic problem since benign (perinephric hematoma, urinoma, extramedullary hematopoiesis, fibrosis, amyloidosis) and malignant conditions (sarcoma, metastases, primary renal carcinoma) can cause minimal changes in the perirenal space (Urban and Fishman 2000; Sheth et al. 2006). Clinical history and secondary findings can help in further differentiation.

1.3.6 Atypical Findings

Although very unusual, atypical findings may be observed in each presentation form including calcification, necrosis, spontaneous hemorrhage, cyst formation, and heterogeneous enhancement (Heiken et al. 1983).

1.4 Role of Different Imaging Modalities

1.4.1 Ultrasound

Ultrasound is widely accepted as the screening modality for renal mass lesions in patients with flank pain and functional renal impairment. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are superior to ultrasound in diagnosis (higher sensitivity and specificity) and in evaluating the extent of disease.

1.4.2 Computed Tomography and Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography (PET-CT)

Contrast-enhanced multidetector CT and PET-CT are the golden standard in detection, staging, and follow-up of lymphoma.

All presentation forms of renal lymphoma tend to be hypovascular and generally show a homogeneous enhancement. For optimal lesion detection, the CT must be performed in the nephrographic or parenchymal (venous) phase. In the venous phase, the cortex and medulla enhance equivocally, and the risk of missing medullar lesions is minimized. Unenhanced CT can be performed prior to contrast administration to objectivate the lesion enhancement.

Corticomedullary or arterial phase is useful only in examining vascular involvement and excretory phase in examining collecting system involvement.

CT further enables the evaluation of disease extension in adjacent structures and detection of other sites of nodal and extranodal involvement. This is important in initial staging and follow-up, because of the impact on therapy and prognosis.

In this respect, CT/PET-CT scan needs to be combined with thoracic and/or neck CT scan.

PET is more sensitive and specific than CT in detecting small tumor deposits (Moog et al. 1998). Attention should be paid to lesions adjacent to the hilum because they could be masked by FDG in the urine (Zukotynski et al. 2012).

Combination of PET and CT combines the advantages of both techniques and at present has become routine in disease follow-up.

CT can also be used in guiding percutaneous biopsy for lesions difficult to access with ultrasound.

1.4.3 MRI

On MRI, the lymphoid masses are like most renal masses, hypointense on T1-weighted images and iso- or hypointense on T2-weighted images. There is moderate enhancement on enhanced MRI.

Results in literature show that the MRI is equally reliable as CT in detection and characterization of lymphoid lesions (Lowe et al. 2000; Sheth et al. 2006).

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) may show restricted diffusion due to the high cellularity of a lymphoma. ADC ranges of 0,64–0,76 (×10−3 mm2/s) were suggested for a lymphoma in two separate studies (Wu et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013).

Despite these good results, CT remains the golden standard because of its cost-effectiveness, ability to evaluate the chest, and availability.

MRI is useful in patients with iodinated contrast allergy or renal insufficiency (Sheth et al. 2006). MRI has perspectives in future for the evaluation of bone marrow involvement.

1.5 Diagnostic Approach

Usually, the radiologic image is sufficient to establish the diagnosis of renal lymphoma. In most cases, the diagnosis is already known before imaging, due to nodal biopsy at initial presentation.

When a renal lesion has characteristics suggesting renal lymphoma, image-guided biopsy is recommended for diagnosis and further therapeutic management (Sheth et al. 2006).

2 Renal Sarcoma

2.1 General Features

Two subtypes are discriminated: primary and secondary sarcoma. The secondary form is further subdivided into renal metastases or direct extension of a retroperitoneal sarcoma. The secondary subgroup is more frequent (Pickhardt et al. 2000). The sarcomatoid type of RCC is not included.

Renal metastases from sarcoma are very rare and are often dependent on the location of the primary lesion. Extremity sarcomas tend to spread to the lungs, whereas retroperitoneal and gastrointestinal sarcomas often spread to the liver (Greene et al. 2006).

Primary renal sarcoma is a very rare presentation form of sarcoma. 1.1 % of malignant renal tumors are sarcomas (Jenkins et al. 1971; Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987; Prasad et al. 2005).

Renal sarcoma affects patients in their fourth to seventh decades, with a slight male preponderance.

Patients often present with an abdominal mass, flank pain, hematuria, and sometimes weight loss. Occasionally, renal sarcoma is an incidental finding (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987).

2.2 Pathogenesis

Each type of mesenchymal cell in the kidney can develop into a different histological type of sarcoma. About 11 histological subtypes are distinguished: liposarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma (ES), osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and synovial sarcoma.

2.3 Imaging Features

Again, two growth patterns are seen in sarcoma: the expansile and the infiltrative growth pattern. Rhabdomyosarcoma and angiosarcoma present more often as an infiltrative lesion, leiomyosarcoma and the other sarcoma subtypes more often as an expansile mass (Pickhardt et al. 2000).

Imaging is variable and depends on the nature and the degree of differentiation of the tumor components. Sarcomas are rapid-growing, large tumors, but these are not specific features enabling the diagnosis. In general, renal sarcomas cannot be differentiated from renal cell carcinomas on imaging.

Some signs can suggest a preoperative diagnosis such as a mass that arises from the renal sinus or capsule, the absence of extension of the mass beyond its pseudocapsule, the highly vascularized areas, and the areas of necrosis (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987). Some subtypes have specific characteristics.

The MRI appearance of renal sarcomas is rarely discussed in current literature. Sarcomas tend to be of intermediate to hypointense signal intensity on T1-weighted MR imaging and of intermediate to hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted MR imaging (Billingsley and Restrepo 2006).

2.3.1 Liposarcoma

Liposarcoma is the most common retroperitoneal malignant tumor (Surabhi et al. 2008). It arises from nonfat-containing areas in the kidney such as the capsule and rarely the parenchyma (Shirkhoda and Lewis 1987).

Their imaging appearance is strongly dependent on their histological subtype (well-differentiated, myxoid, round cell, pleomorphic, and dedifferentiated subtypes).

Well-differentiated liposarcomas contain mainly macroscopic fat. Round cell and pleomorphic liposarcomas present as a soft tissue mass; the myxoid type has a cystic appearance, while dedifferentiated liposarcomas can present intralesional calcifications or ossifications (Fig. 10) (Secil et al. 2005; Surabhi et al. 2008). Liposarcomas tend to be hypovascular.

Differential diagnosis of angiomyolipoma with liposarcoma can be difficult if the angiomyolipomas are large and exophytic. The presence of large intratumoral vessels, intralesional hemorrhage, sharp parenchymal defect, and associated angiomyolipomas favors the diagnosis of an angiomyolipoma (Wang et al. 2002; Israel et al. 2002).

2.3.2 Hemangiopericytoma and Angiosarcoma

A hemangiopericytoma is a soft tissue vascular tumor that originates from the Zimmerman pericytes. On imaging, it presents as a large, lobulated, well-defined, hypervascular mass, usually with necrotic areas and calcifications. Differential diagnosis with renal cell carcinoma is difficult. Hemangiopericytoma often occurs in younger patients (fourth decade) than renal cell carcinoma (Brescia et al. 2008; Surabhi et al. 2008).

Angiosarcoma is a rare tumor that arises from endothelial cells. Renal involvement is mostly the result of metastases from primary dermal or visceral angiosarcoma. On imaging, it presents as a heterogeneous hypervascular infiltrative mass. Sometimes, hemorrhage can be observed on unenhanced CT or MRI. Calcification can be present. The role of carcinogens (arsenic, thorium dioxide, vinyl chloride exposure) as in hepatic angiosarcoma has not been established in renal angiosarcoma (Leggio et al. 2006; Yu et al. 2008).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree