Chapter Outline

Postoperative Alterations of the Pancreaticobiliary Tract and Gastrointestinal Tract

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Since the first clinical application of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in the early 1990s, MRCP has evolved from a technique with questionable potential for imaging of the biliary tract and pancreatic duct to one that is now recognized as a pivotal tool for diagnosis of pancreaticobiliary disease. In fact, the evolution of MRCP has been such that at many centers, MRCP has replaced diagnostic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in a number of clinical scenarios. A prospective survey revealed that MRCP findings enhance the diagnostic confidence of gastroenterologists and decrease the need for invasive procedures.

For many years, ERCP has been considered the standard of reference for imaging of the biliary tract and pancreatic duct because of its ability to render high-quality images of the ducts. However, ERCP is an invasive examination associated with complications that occur in up to 5% of all attempts and that range from subclinical to life-threatening. Those complications include pancreatitis, hemorrhage, cholangitis, and gastrointestinal tract perforation.

The relatively rapid acceptance of MRCP is related, in large part, to its ability to provide images of the ducts similar to those of ERCP. These images can be obtained without the associated complications of ERCP while offering comparable sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. In addition, MRCP is readily performed in the outpatient setting and does not expose patients to ionizing radiation. In most instances, performance of MRCP does not require administration of sedation. In contrast to ERCP, MRCP readily depicts ducts proximal to a high-grade obstruction as well as ducts in patients with surgical alterations of the biliary tract and gastrointestinal tract, such as biliary-enteric anastomoses. Although ERCP yields exquisite images of the ductal systems, it provides no direct information about the solid organs and vessels of the abdomen. However, when MRCP is performed in conjunction with conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and, when necessary, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), a comprehensive examination is achieved. This information assists in determining resectability of neoplasms, such as pancreatic carcinoma, and in detecting complications of primary sclerosing cholangitis, such as cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma.

Technique

Before acquisition of the MRCP image, many advocate the use of heavily T2-weighted, non–fat-suppressed sequences, such as the half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo spin-echo (HASTE) sequence, to provide an overview of the entire abdomen ( Fig. 75-1A ). These comprehensive images allow visualization of the solid organs as well as of the pancreaticobiliary tract and gallbladder. The MRCP image is then acquired. This can be achieved by use of a two-dimensional (2D), heavily T2-weighted, fat-suppressed, breath-hold sequence. This sequence can provide single thick-slab images with slice thicknesses ranging from 10 to 70 mm and multiple thin-slab images with slice thicknesses ranging from 2 to 5 mm ( Fig. 75-1B -D). The images depict the biliary tract, pancreatic duct, and gallbladder as high signal intensity structures. Multiple acquisitions are conducted in the coronal and coronal oblique planes to optimally image the ducts. In addition, the axial plane is useful in distinguishing stones, which layer in the dependent portion of the duct, from pneumobilia, which is nondependent. In general, the thin-slab images allow improved delineation of the finer details of the ductal systems, whereas the thick-slab images provide comprehensive views of the ducts that assist in the depiction of diffuse ductal diseases, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis. Although the thin-slab images may be manipulated with a maximum intensity projection (MIP) algorithm, most diagnostic decisions are made directly from the 2D images. In interpreting MIP images, it should be remembered that at times the high signal intensity that is characteristic of MIPs may obscure subtle intraductal filling defects, such as small stones.

More recently, three-dimensional (3D) sequences used in conjunction with respiratory triggering, thin sections (1-2 mm), and high matrices have been used to generate MRCP images. With this technique, the source images can be viewed as individual images, much like MRCP images acquired with 2D sequences. The advantage of 3D imaging is that it yields isotropic images that can be reformatted in any plane, thereby obviating the need to acquire images in multiple planes.

Some investigators advocate the performance of contrast-enhanced MRCP with 3D T1-weighted sequences and hepatocyte-specific contrast agents that are excreted into the biliary tract. These agents are divided into two major categories: manganese-based agents (no longer available in the United States) and gadolinium-based agents, such as gadobenate dimeglumine and gadoxetate. MRCP performed with T1-weighted sequences and a manganese-based agent has been shown useful in the detection of biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and in depicting the intrahepatic bile ducts in living liver transplant donor candidates.

The 2D and 3D techniques allow excellent depiction of the pancreatic duct in most cases. However, in those instances in which the pancreatic duct is not well visualized or determination of pancreatic exocrine function is desired, secretin-enhanced MRCP may prove useful.

Whereas the majority of MRCP studies are performed on 1.5T MRI scanners, a growing number of MRCP studies are being performed on 3.0T MRI scanners, given their increased availability and use. Although 3T scanners may improve image quality and therefore improve ductal delineation, 3T scanners produce increased susceptibility artifacts compared with 1.5T scanners.

Clinical Applications

Bile Duct Calculi

Historically, many patients with suspected choledocholithiasis and a normal sonogram or computed tomography (CT) scan underwent diagnostic ERCP to determine the presence or absence of stones. The introduction of MRCP provided a long-awaited, noninvasive alternative to diagnostic ERCP for the detection and exclusion of common bile duct stones. However, for MRCP to gain widespread acceptance, it had to compare favorably with ERCP. In an analysis of 72 patients studied with intraoperative cholangiography and ERCP, Frey and associates found a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 98% for ERCP in the setting of suspected choledocholithiasis.

Initial reports of MRCP in the detection of common bile duct stones noted sensitivities as low as 81%. However, technical advances in MR hardware and the introduction of sequences that allowed breath-hold imaging and that suppressed artifacts arising from surgical clips and bowel gas improved MRCP image quality substantially, which in turn enhanced the MRCP diagnosis of common bile duct stones. Subsequent studies performed with state-of-the-art scanners and sequences demonstrated sensitivities of 90% to 100%, specificities of 92% to 100%, and positive predictive value of 96% to 100%, matching and in most cases exceeding those of ERCP. Although many physicians focus on the sensitivity offered by a technique, it is equally important to consider the negative predictive value. The negative predictive values of MRCP are high, ranging from 96% to 100%. Therefore, if an MRCP study is interpreted as negative for common duct stones, one can be confident that stones are not present in most cases and ERCP can be avoided. In fact, one of the major benefits of MRCP in the setting of suspected biliary calculi is the reduction of unnecessary ERCP studies.

In the setting of symptomatic gallstones, MRCP has been shown to be highly accurate in the detection of coexistent choledocholithiasis in patients with high, moderate, and low risks for harboring common bile duct stones based on clinical, laboratory, and sonographic findings. Kim and colleagues recommended that MRCP be performed before cholecystectomy in patients with a moderate or high risk of common bile duct stones in an effort to reduce morbidity associated with undetected choledocholithiasis and to decrease the performance of purely diagnostic ERCP.

In addition to the detection of common bile duct stones, MRCP performs well in the detection of intrahepatic stones. One study revealed that the sensitivity and specificity of MRCP for detection of intrahepatic stones were 97% and 93%, respectively, whereas those of ERCP were 59% and 97%, respectively.

Both extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile duct stones are seen as well-defined, low signal intensity filling defects in the high signal intensity bile ( Fig. 75-2 ). MRCP has been shown to detect stones as small as 2 mm even in normal-caliber ducts. Although the coronal and coronal oblique planes demonstrate stones in most instances, at times it is helpful to acquire MRCP images in the axial plane to detect small stones and to differentiate stones that lie in the dependent portion of the duct from pneumobilia that lies in the nondependent portion of the duct ( Fig. 75-3 ).

Although MRCP performs well in the detection of stones, one must be aware of mimickers of stones that may result in false-positive diagnoses. These include pneumobilia, en face visualization of the cystic duct inserting into the bile duct, and compression of the duct by an adjacent vessel.

Neoplasms

MRCP is useful in the evaluation of suspected malignant neoplasms of the pancreaticobiliary tract. Multiple studies have demonstrated the ability of MRCP to determine the presence, level, and type of malignant disease with a high degree of accuracy. In a study of 62 patients with biliary obstruction, Kim and associates demonstrated that the addition of conventional MRI to MRCP significantly improves the accuracy in the diagnosis of pancreaticobiliary disease and aids in the differentiation of benign from malignant causes of biliary dilation. When MRCP is supplemented by conventional MRI and MRA, a comprehensive examination results that allows depiction of the pancreaticobiliary tract, solid organs, and vasculature, which in turn permits determination of resectability of neoplastic disease. This comprehensive examination is most beneficial for patient care. Specifically, if a neoplasm is deemed resectable, the patient should be spared an unnecessary ERCP examination and stent placement as there is no established role for preoperative biliary drainage by ERCP in these patients. On the other hand, if a neoplasm is deemed unresectable, the patient may be spared an unnecessary laparotomy. An additional advantage of MRCP offered in the setting of pancreaticobiliary tract malignant neoplasms is that MRCP depicts the entire biliary and pancreatic duct even in the presence of high-grade strictures and allows planning of surgical and percutaneous interventions.

Pancreatic Carcinoma

With the use of newer scanners and sequences that afford high-resolution imaging, MRCP not only readily identifies the ductal dilation that occurs as the result of pancreatic carcinoma but also depicts the malignant ductal strictures themselves and localizes the neoplastic process to the pancreas. MRCP depicts bile duct involvement by pancreatic carcinoma as an abrupt transition between the dilated suprapancreatic duct and the markedly narrowed intrapancreatic duct, often referred to as a rat-tail configuration ( Fig. 75-4A, B ). In the case of pancreatic head carcinoma obstructing the bile and pancreatic ducts, MRCP shows dilation of both ducts, known as the double duct sign. Whereas the double duct sign is often seen in association with pancreatic head carcinoma, it is a nonspecific sign that may be due to a benign or malignant process involving the pancreatic head. In the setting of carcinoma involving the body or tail of the pancreas, the ductal dilation is limited to the pancreatic duct proximal to the obstruction. Because the entire pancreatic duct is rarely depicted on a single 2D MRCP image, axial MRCP images are often useful in demonstrating the obstructing tumor and the transition between the dilated and nondilated pancreatic duct.

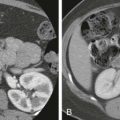

The performance of conventional MRI and MRA in conjunction with MRCP allows determination of resectability ( Fig. 75-4C, D ). T1-weighted, fat-suppressed, unenhanced sequences are particularly helpful in depicting even small tumors in the pancreas. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas are manifested as areas of low signal intensity against the high signal intensity of the normal pancreatic parenchyma. In addition to detection of the primary tumor, conventional MRI is useful in detecting liver metastases, nodal enlargement, and peritoneal carcinomatosis. MRA plays an important role in detecting neoplastic involvement of the celiac axis, hepatic artery, superior mesenteric artery and vein, and portal vein. In patients with unresectable pancreatic carcinoma, MRCP yields information important in planning of palliative and endoscopic drainage procedures.

In a prospective study of 124 patients with clinical and sonographic findings strongly suggestive of pancreatic neoplasia, Adamek and associates showed that the sensitivity and specificity of MRCP in diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma (84% and 97%) exceeded those of ERCP (70% and 94%). Unfortunately, the distinction between pancreatic carcinoma and focal chronic pancreatitis will likely remain a problem in some instances despite technical improvements in MRI, MRA, and MRCP.

Cholangiocarcinoma: Hilar and Distal Duct

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma is the most common manifestation of cholangiocarcinoma and is depicted as a high-grade stricture of the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts. In the past, much emphasis was placed on palliative procedures, such as percutaneous biliary drainage and endoscopic stent placement, because of the poor prognosis associated with this neoplasm. However, with the advent of improved surgical and radiation therapy techniques, greater attention is directed toward imaging examinations that assist in determining disease extent and resectability.

During the past decade, MRCP has become an important tool in the evaluation of cholangiocarcinoma in general and hilar cholangiocarcinoma in particular. Like direct cholangiography, MRCP demonstrates the marked narrowing of the proximal extrahepatic bile duct, the often-present extension to the central right and left hepatic ducts, and the dilation proximal to the obstruction ( Fig. 75-5A, B ). Because MRCP readily depicts ducts proximal to high-grade obstructions that are often not opacified at ERCP, MRCP typically is superior in determining disease extent and resectability. As with other pancreaticobiliary tract neoplasms, MRI performed in association with MRCP offers the added advantage of demonstrating disease that has extended from the ducts into the liver and adjacent structures ( Fig. 75-5C ). These factors have allowed MRCP to assume an important role in the noninvasive evaluation of hilar cholangiocarcinoma and to facilitate planning of surgical, percutaneous, and radiation therapy procedures. Park and coworkers demonstrated that MRCP combined with MRI provides information about cholangiocarcinoma extent and resectability comparable to that of multidetector CT with direct cholangiography.

Cholangiocarcinomas that involve the extrahepatic duct distal to the confluence are often referred to as the distal duct type. Distal duct cholangiocarcinomas are seen as strictures or intraductal polypoid masses resulting in biliary obstruction on both MRCP and ERCP. In a retrospective study of 50 patients with extrahepatic bile duct cholangiocarcinoma and 23 patients with benign strictures, MRCP was shown to have an accuracy comparable to that of ERCP in making the distinction between cholangiocarcinoma and benign strictures. Distal duct cholangiocarcinoma confined to the intrapancreatic bile duct is difficult to distinguish from pancreatic head carcinoma with either MRCP or ERCP ( Fig. 75-6 ). However, the clinical impact of this deficiency is of no consequence as the treatment of both tumors is identical and is predicated on resectability.

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm of the Pancreas

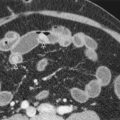

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) are categorized as main duct type and branch duct type, depending on the duct of origin, and may be benign or malignant. IPMNs are well demonstrated on MRCP because they produce mucin, which appears as high signal intensity within the ducts. MRCP can reveal the entire spectrum of IPMNs—main duct dilation, cystic dilation of the side branches, nodules, septa, and intraductal filling defects—and is able to show communication between the tumor and the pancreatic duct ( Fig. 75-7 ). A study of 34 IPMNs in 31 patients examined with MRCP and correlated with surgical and pathologic findings revealed that intraductal filling defects are indicative of malignant disease and that diffuse dilation of the main pancreatic duct of more than 15 mm in main duct–type tumors is strongly associated with malignant transformation. In branch duct–type tumors, the absence of main pancreatic duct dilation suggests a benign tumor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree