and Arumugam Rajesh2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

(2)

Department of Radiology, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Tr Leicester General Hospital, Leicester, UK

Prostate

Case 7.1

Brief Case Summary

60 year old man with elevated PSA and prior history of intravesical BCG for bladder carcinoma.

Imaging Findings

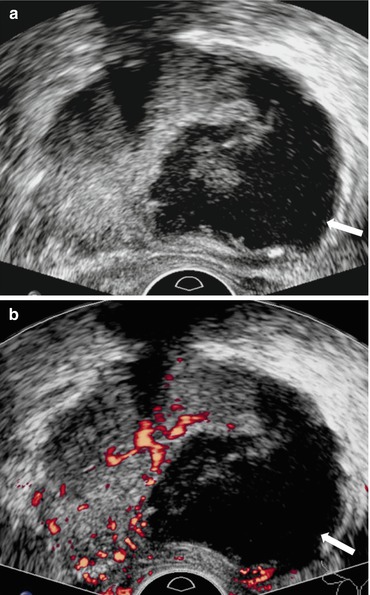

Transrectal ultrasound shows an isoechoic lesion in left lobe of the prostate gland with a contour deformity along the left posterolateral margin of prostate (Fig. 7.1). Contrast enhanced CT shows the same area to be hypo enhancing with loss of the left recto-prostatic angle (Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.1

Transrectal ultrasound shows an isoechoic lesion in left lobe of the prostate gland with a contour deformity along the left posterolateral margin of prostate

Fig. 7.2

Contrast enhanced CT shows the same area to be hypo enhancing with loss of the left recto-prostatic angle

Differential Diagnosis

Prostate carcinoma.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Granulomatous prostatitis secondary to BCG therapy.

Intravesical BCG is an accepted method of therapy for bladder cancer. About 40 % of these patient will subsequently show elevation of PSA and approximately 10 % will have clinically symptomatic prostatitis which occur due to reflux of BCG into the prostate.

Granulomatous prostatitis may be secondary to BCG or idiopathic (termed nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis, NSGP). NSGP usually demonstrates non necrotic lesions with low T2 signal and ADC values mimicking cancer. Prostatitis secondary to BCG usually demonstrates necrosis. Inflammation may spread to peri-prostatic tissues with loss of normal anatomical landmarks such as the recto-prostatic angle.

A prior history of BCG therapy with accompanying imaging findings usually allow for a confident diagnosis. The PSA in most cases returns to normal within 4–6 months of starting anti-tubercular therapy.

Imaging Pitfalls

The low T2 signal lesion in the peripheral zone and diffusion restriction may mislead the radiologist into considering malignancy as the diagnosis, however the presence of necrosis, lack of rapid wash-out, and high choline peak on MR spectroscopy assist in differentiation.

Teaching Points

Granulomatous prostatitis can occur secondary to intravesical BCG therapy for bladder carcinoma.

Prior history of BCG exposure coupled with imaging findings usually point to the correct diagnosis and biopsy is usually unnecessary.

Case 7.2

Brief Case Summary

55 year old male with rising PSA levels and abnormal digital rectal examination (DRE), past h/o tuberculosis.

Imaging Findings

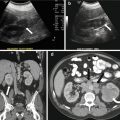

Transrectal ultrasound image demonstrates a well demarcated hypoechoic collection in the left lobe of prostate peripherally placed. It does not show vascularity like the surrounding normal gland (Fig. 7.3a, b).

Fig. 7.3

(a, b) Transrectal ultrasound image demonstrates a well demarcated hypoechoic collection in the left lobe of prostate peripherally placed. It does not show vascularity like the surrounding normal gland

Differential Diagnosis

Carcinoma prostate.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Prostatic tubercular abscess

Genito urinary tuberculosis constitutes 10–14 % of extrapulmonary tuberculosis cases. Prostatic involvement is rare. The usual mode of infection is hematogenous spread or descending infection from the upper urinary tract. Risk factors include prior history of TB, immunocompromised status or intravesical BCG therapy.

Imaging is sought once DRE is abnormal or PSA levels rise. USG is the initial modality of choice. It displays a well marginated hypoechoic collection with no internal vascularity, few internal echoes may be visible. MRI reveals T2 heterogeneity within a well marginated lesion. Diffusion restriction may be present confounding the diagnosis. However post contrast images reveal some amount of necrosis, unusual for a malignancy. Biopsy if often necessary to reach a definite conclusion. Urine PCR has shown good sensitivity and specificity in diagnosis of Genito-urinary TB in general.

Pitfalls

Tubercular abscess of the prostate may mimic a malignancy with low T2 signal and ADC values. However presence of necrosis and lack of rapid washout and choline elevation on MRS are clues that help to rule out a malignant lesion.

Teaching Point

Tubercular abscess in the prostate is rare

It may closely mimic malignancy on clinical and laboratory examination- multiparametric MRI often allows confident differentiation of these entities.

Case 7.3

Brief Case Summary

A 62 year old male with hard prostate on digital rectal examination and elevated PSA levels.

Imaging Findings

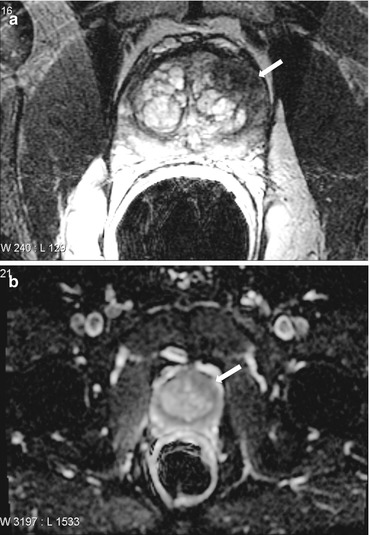

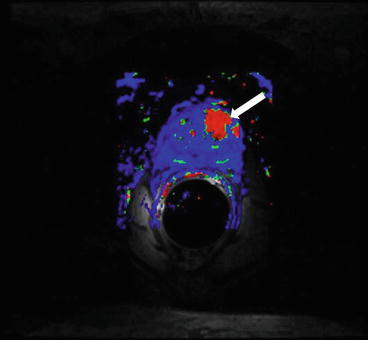

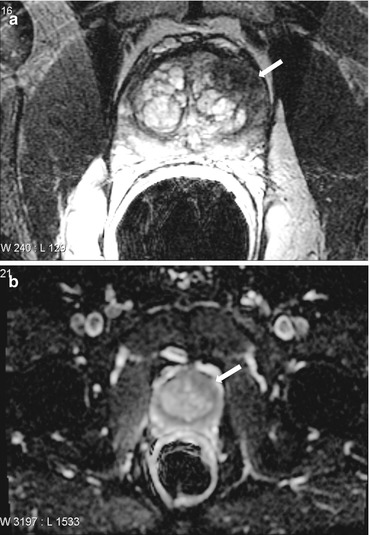

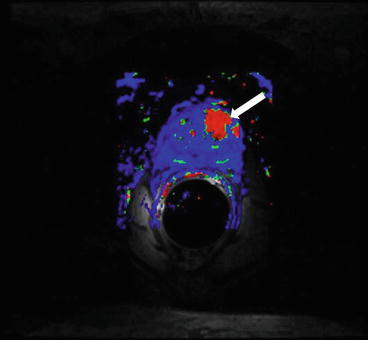

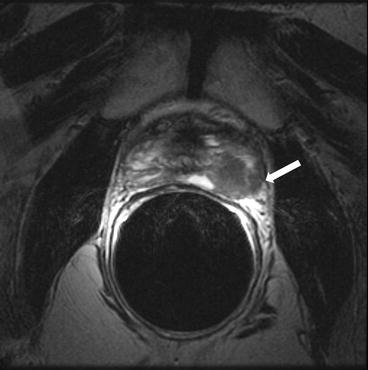

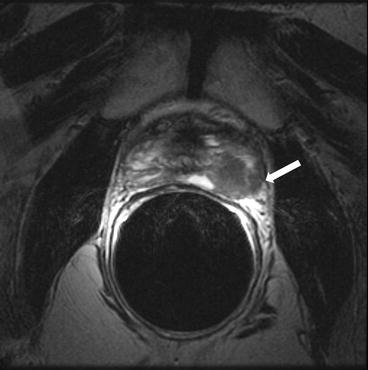

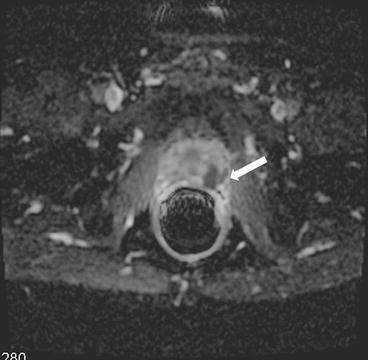

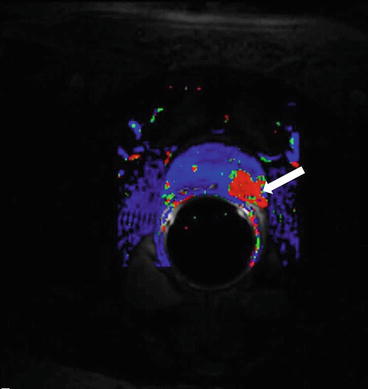

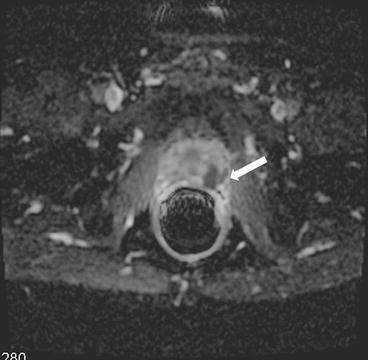

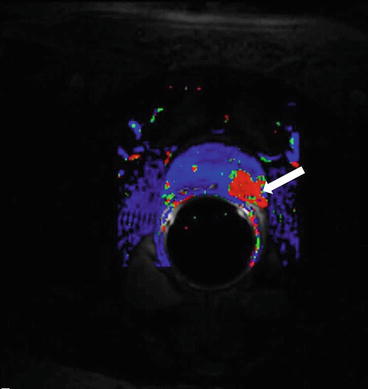

Axial T2 weighted images (Fig. 7.4a, b) reveal an ill defined hypointense nodule involving the central gland in the mid prostate on left side. There is extension into the peripheral zone as well. The corresponding ADC maps reveal a low ADC, dynamic contrast enhancement color maps show rapid washout kinetics (red) in the region of t2 signal abnormality (Fig. 7.5).

Fig. 7.4

(a, b). Axial T2 weighted images reveal an ill-defined hypointense nodule involving the central gland in the mid prostate on left side. There is extension into the peripheral zone as well

Fig. 7.5

Corresponding ADC maps reveal a low ADC, dynamic contrast enhancement color maps show rapid washout kinetics (red) in the region of t2 signal abnormality

Differential Diagnosis

benign hypertrophic nodule

post radiation changes

chronic prostatitis

Diagnosis and Discussion

Carcinoma prostate.

Prostatic cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death among American men, after lung cancer. Imaging and MRI in particular play a key role in identification of the malignancy and its management.

Central gland (transitional zone and central zone combined) tumors pose a unique challenge as the normal T2 hyperintense background of the peripheral zone is absent, moreover there is significant overlap in T2 signals of normal central gland tissue and tumor nodules. Hence imaging multi-parametric MRI (MP-MRI) is paramount. Tumors in this location often present with ill-defined margins and a uniform low T2 signal. Since these tumors are highly cellular they display low ADC values and restricted diffusion. Neovascularity within their substance manifests as rapid wash-in and subsequent wash-out of gadolinium on dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) scans. These generally appear as red areas on post processed color maps (provided there is at least >20 % washout).

Other features of a central gland tumor are lenticular shape, absence of a discernable capsule and invasion of the anterior fibromuscular stroma, asymmetric rapid wash-in/wash-out kinetics and elevated choline on MRS also suggest the diagnosis although no single feature is pathognomonic.

Pitfalls

Chronic prostatitis may mimic cancer with a low T2 signal and mild diffusion restriction. However it usually doesn’t produce mass effect or a contour deformity of the gland. Furthermore the degree of diffusion restriction on DWI and wash-out on DCE are less than that of prostate cancer.

Hypertrophic nodule – usually arise in central gland, they can be differentiated from cancer by their well defined capsulated margins, they rarely reach the capsule and normal tissue is seen interposed between them and the capsular margin. The MRS generally reveals a normal spectrum. Symmetric contrast enhancement kinetics are usually seen.

Post radiation changes may also demonstrate a low t2 signal secondary to fibrosis – these foci do not show diffusion restriction, rapid washout or choline peaks on MP-MRI.

Teaching Point

Interpretation of MP-MRI relies on sound knowledge of normal prostatic zonal anatomy, typical findings of cancer and that its mimics.

No single imaging finding is pathognomonic for prostatic cancer.

Case 7.4

Brief Case Summary

A 70 year old male with rising PSA levels and normal clinical examination.

Imaging Findings

Axial T2 weighted image demonstrates a well marginated uniformly hypointense lesion in the mid gland located within the normal T2 hyperintense stroma of the peripheral zone (PZ) (Fig. 7.6).

Fig. 7.6

Axial T2 weighted image demonstrates a well marginated uniformly hypointense lesion in the mid gland located within the normal T2 hyperintense stroma of the peripheral zone (PZ)

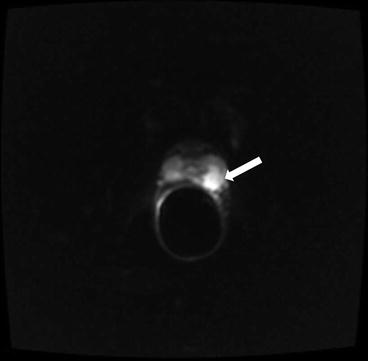

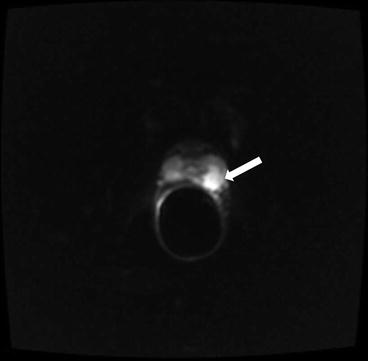

It is seen to extend up to and beyond the capsular margin into the periprostatic fat. The recto-prostatic angle is obliterated and ipsilateral neurovascular bundle is invaded. Restricted diffusion with is seen with high signal on DWI and corresponding low signal on ADC maps (Figs. 7.7 and 7.8). Color perfusion maps obtained from DCE MRI shows rapid wash-out in the lesion (red) (Fig. 7.9).

Fig. 7.7

Lesion is seen to extend up to and beyond the capsular margin into the periprostatic fat. The recto-prostatic angle is obliterated and ipsilateral neurovascular bundle is invaded

Fig. 7.8

Restricted diffusion which is seen with high signal on DWI and corresponding low signal on ADC maps

Fig. 7.9

Color perfusion maps obtained from DCE MRI shows rapid wash-out in the lesion (red)

Differential Diagnosis

Benign hypertrophic nodule in PZ.

Displaced central zone

Post radiation changes

Pseudolesion in the midline of PZ

Diagnosis and Discussion

Carcinoma prostate in peripheral zone of left lobe mid gland with Extracapsular extension (ECE).

The normal peripheral zone displays a relatively high signal on T2 images owing to fluid filled ducal and acinar components. This has the advantage of providing excellent contrast resolution for detection of the T2 hypointense tumours.

Carcinoma appears uniformly low in T2 signal compared to bright surrounding PZ. Hence T2 images are useful for initial localization of the abnormality. But given the myriad mimics of carcinoma, multiparametric imaging is used for further characterization.

Carcinoma usually (in addition to a low T2 signal) demonstrates ill defined margins, low ADC values and rapid wash-out of contrast on DCE scans. They also show raised choline peaks on MRS. Once each of these features are present, the diagnosis can be made with reasonable certainty.

The normal gland capsule is a low signal intensity rim (of about 1 mm thickness) surrounding the gland. Breach of this margin constitutes ECE, this upstages the tumor from one that is localized to the prostate (T2) to one that is locally advanced (T3), in addition to conferring a poorer prognosis. Extracapsular extension is common and exquisitely demonstrated by high resolution t2 images. The primary imaging signs of ECE are:

(a)

Asymmetric capsular bulge with irregular margins

(b)

Obliteration of normal recto-prostatic angle

(c)

Asymmetry or non visualization of the neurovascular bundle

(d)

Encasement of the neurovascular bundle

(e)

Seminal vesicle invasion.

The implications of detecting ECE on MRI are myriad. Patients with ECE have a higher rate of local recurrence, invasion of neurovascular bundles may alter surgical approach. Some patients may refuse surgery given that it may not be possible to salvage the neurovascular bundles.

Pitfalls

Post biopsy haemorrhage may appear as a low T2 signal focus, a prior history of biopsy coupled with a hyperintense focus on T1 images avoids an erroneous diagnosis.

Benign nodule in PZ – usually shows a well defined border, rarely reaches capsule and shows bilateral symmetric wash-out kinetics. The T2 signal of these nodules matches that of the central gland.

Displaced central zone – may mimic a PZ cancer when it gets displaced by a hypertrophied TZ, it is also of low T2 signal. Typical location at base of prostate and bilateral symmetry help differentiate this entity from malignancy.

Post radiation changes – result in fibrosis and uniformly low t2 signal in the gland, hence t2 imaging cannot be relied upon. Radiation changes however do not display restricted diffusion, rapid wash-out or elevated choline as malignancies do.

Pseudolesion in midline of PZ – a focus of low T2 signal and low ADC can often be found in the midline, it is thought to be the point of fusion of the prostatic capsule with the adjacent fascia. Lack of rapid enhancement, concave contour and midline location should aid in differentiation from its sinister counterpart.

Teaching Point

Carcinoma appears as an ill defined lesion of low T2 signal in a normally hyperintense PZ.

Detection of ECE, neurovascular invasion and seminal vehicle invasion are essential as they significantly alter patient management and confer a poor prognosis.

Seminal Vesicle and Vas deferens

Case 7.5

Brief Case Summary:

24 year old male with abdominal pain

Imaging Findings

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis without intravenous contrast demonstrates an absent left seminal vesicle. A normal right seminal vesicle is noted (Fig. 7.10, arrow).

Fig. 7.10

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis without intravenous contrast demonstrates an absent left seminal vesicle. A normal right seminal vesicle is noted (arrow)

Differential Diagnosis

Seminal vesicle agenesis, seminal vesicle hypoplasia

Diagnosis and Discussion

Seminal vesicle agenesis (in patient with cystic fibrosis).

Seminal vesicle agenesis can occur in two distinct settings. The first setting involves an embryological insult to the mesonephric duct while the second is seen in the setting of mutations involving the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR). Both settings may have corresponding abnormalities of the vas deferens (typically agenesis), with associated renal abnormalities only seen with the former, particularly if the insult takes place before ureteral budding (which occurs at approximately 7 weeks gestation). Seminal vesicle agenesis associated with mutations of the CFTR is thought to occur secondary to intraluminal obstruction by thick and tenacious secretions.

Asymptomatic patients require no treatment. Symptomatic patients typically complain of infertility. On occasion, an ectopic vas deferens may insert into a Mullerian duct remnant resulting in cystic dilatation leading to pain, hematospermia and/or epididymitis. A variety of surgical options may be considered for symptomatic patients including vasoepididymostomy and transuretheral resection of the ejaculatory duct.

Pitfalls

Absence of the seminal vesicle is diagnostic for seminal vesicle agenesis. A small seminal vesicle with fewer septa suggests the presence of seminal vesicle hypoplasia, though no diagnostic criteria have been established.

Teaching Points

1.

Absence of the seminal vesicle should prompt an evaluation for associated upper urinary tract abnormalities and/or evidence for cystic fibrosis.

2.

Absence of the ipsilateral kidney suggests an embryological insult before 7 weeks gestation.

3.

The most common symptom is infertility for which a variety of surgical options may be considered.

Case 7.6

Brief Case Summary

42 year old male with abdominal pain

Imaging Findings

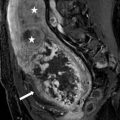

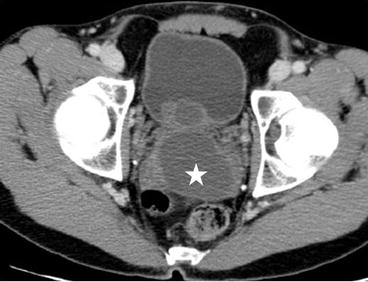

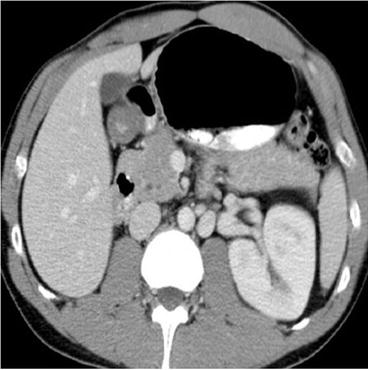

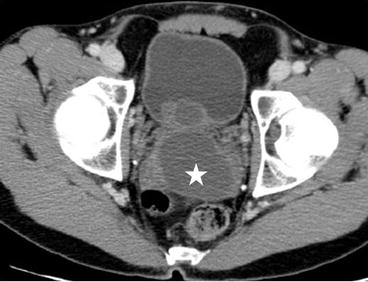

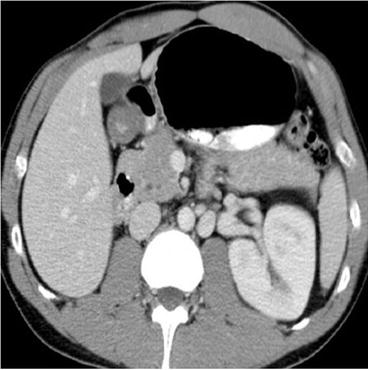

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrates an off-midline oval fluid-attenuation mass posterior to the bladder (asterisk, Fig. 7.11). Note is made of an absent right kidney (Fig. 7.12).

Fig. 7.11

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrates an off-midline oval fluid-attenuation mass posterior to the bladder (asterisk)

Fig. 7.12

Axial CT demonstrates an absent right kidney

Differential Diagnosis

Bladder diverticulum, seminal vesicle cyst, cyst of the vas deferens, prostatic utricle cyst, tortuous hydroureter.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Seminal vesicle cyst (with agenesis of the right kidney).

Cysts of the seminal vesicle may congenital or acquired. They are usually discovered between the second and third decades of life and may be related to the onset of sexual activity. Congenital cysts may be isolated findings or may be associated with upper urinary tract abnormalities (such as renal agenesis) or autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (particularly with the presence of bilateral cysts). Clinical presentation is variable, ranging from incidental lesions in asymptomatic patients, to pelvic discomfort, recurrent infections (prostatitis, urinary tract infection and/or epididymitis) as well as hematospermia.

CT imaging demonstrates the presence of a well-defined fluid density retrovesicular mass arising in the expected region of the seminal vesicle, above the level of the prostate gland. The majority of the lesion is less than 5 cm in maximal diameter. Seminal vesicle cysts have variable signal intensity on T1 weighted MR images (due to the presence of hemorrhagic and/or proteinacious debris) but typically demonstrate high signal on T2 weighted imaging. No enhancing components are observed after the administration of contrast medium. Sonography demonstrates the presence of a cystic mass, although minimal complexity may be observed due to intraluminal debris.

Asymptomatic lesions require no diagnostic or therapeutic intervention. Excision may be performed for symptomatic lesions, particularly if they present with bowel or bladder obstruction.

Pitfalls

There are a number of cystic masses that may arise in a similar location, which can be potentially differentiated by their location and relationship to adjacent structures. Intraprostatic cysts include utricle and Mullerian duct cysts (both of which are midline) as well as ejaculatory duct cysts (off-midline or paramedian) and prostatic retention cysts (lateral location). Extraprostatic cysts include cysts of the vas deferens and Cowper duct cysts, with the latter occurring at the level of the posterior urethra. Bladder diverticulae demonstrate a connection to the bladder lumen while multiplanar imaging can allow differentiation of seminal vesicle cysts from a tortuous hydroureter.

Teaching Points

1.

Seminal vesicle cysts are benign findings that are often asymptomatic for which no diagnostic or therapeutic intervention is needed. Excision may be considered if symptoms are present, particularly with the presence of bladder outlet obstruction.

2.

Seminal vesicle cysts are commonly associated with upper urinary tract abnormalities such as renal agenesis. The presence of bilateral seminal vesicle cysts should prompt an evaluation for underlying autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

3.

There are a number of potential mimickers of this lesion in the pelvis. Categorizing lesions first by their relationship to the prostate gland (intra or extraprostatic) and then their location with respect to the midline (median, paramedian and lateral) allows for an algorithmic approach to the radiologic interpretation.

Case 7.7

Brief Case Summary:

77 year old male with abdominal pain.

Imaging Findings

Frontal radiograph of the pelvis demonstrates bilateral, symmetric, and tubular calcifications (Fig. 7.13).

Fig. 7.13

Frontal radiograph of the pelvis demonstrates bilateral, symmetric, and tubular calcifications

Differential Diagnosis

Vas deferens calcifications, bladder calculi, calcified pelvic neoplasm, phleboliths.

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Vas deferens calcifications

Vas deferens calcifications are benign findings, most often seen in diabetic patients. Other reported associations include secondary hyperparathyroidism as well as chronic infections such as tuberculosis or schistosomiasis. Idiopathic cases are exceedingly rare.

Imaging finding are fairly characteristic with calcifications seen lining the wall of the vas deferens, often bilateral and symmetric. Chronic inflammation from tuberculosis may lead to the deposition of intraluminal or intramural calcifications. As opposed to the more common diabetes related calcifications, findings in tuberculosis tend to be unilateral and segmental in distribution.

Unless there is a strong clinical suspicion for tuberculosis or other inflammatory conditions, no treatment is required. In all other cases, the presence of seminal vesicle calcifications gives insight into concurrent endocrine or metabolic derangements that the patient may have.

Pitfalls

Seminal vesicle calcifications have a characteristic pattern allowing for easy differentiation from other causes of pelvic calcifications. A phlebolith is a small calcification found within a vein. On radiographs they often demonstrate a radiolucent center (distinguishing them from ureteral stones) and CT imaging may demonstrate the “comet tail” sign, representing the parent vein.

Teaching Point

1.

Seminal vesicle calcifications are benign findings with a characteristic imaging appearance, most often seen in patients with diabetes.

2.

Other uncommon causes include secondary hyperparathyroidism as well as tuberculosis. Calcifications associated with chronic inflammation tend to unilateral and segmental.

3.

The presence of seminal vesicle calcifications gives insight into concurrent endocrine or metabolic derangements that the patient may have. Unless there is a strong clinical suspicion for tuberculosis or other inflammatory conditions, no treatment is required.

Case 7.8

Brief Case Summary

None.

Imaging Findings

Axial T2 (Fig. 7.14) and T1 without (Fig. 7.15) and with gadolinium (Fig. 7.16) images show enlargement and thickening of the left seminal vesicles (arrows) with associated enhancement.

Fig. 7.14

Axial T2 image shows enlargement and thickening of the left seminal vesicles (arrows)

Fig. 7.15

Axial T1, without gadolinium, image shows enlargement and thickening of the left seminal vesicles (arrows)

Fig. 7.16

Axial T1, with gadolinium, image shows enlargement and thickening of the left seminal vesicles (arrows) with associated enhancement

Differential Diagnosis

Invasion from adjacent prostatic or rectal carcinoma

Diagnosis and Discussion

Seminal vesicle amyloidosis

Seminal vesicle amyloidosis is a common finding seen on autopsy and is related to aging. The incidence increases with age and is about 21 % in patients above 75 years of age. It may occur as a localized finding or may be associated with systemic amyloidosis, the former being more common. When localized, this condition is bilaterally symmetrical with subepithelial amyloid deposits in lamina propria. When related to systemic amyloidosis, the amyloid deposits are seen in blood vessel walls or in muscles.

Patients are generally asymptomatic but rare symptoms include hematospermia and enlargement of seminal vesicles.

Ultrasound may show enlargement of the seminal vesicles. Focal lesions, seen as hypoechoic foci are otherwise indistinguishable from other seminal vesicle masses. CT shows focal or diffuse bilateral enlargement of the gland but is limited in assessing the internal architecture. MRI shows diffuse wall thickening of the seminal vesicle. The amyloid foci are seen as hypointense deposits on T2 and there may be associated areas of hemorrhage which appear hyperintense on T1. The imaging features may simulate tumor deposits, however, contrast enhanced MRI may be able to differentiate the two entities by showing enhancement in latter.

Pitfalls

Seminal vesicle amyloidosis is easily confused with primary tumor or tumor invasion from adjacent structures and has been seen to be responsible for upstaging of various adjacent tumors. Normal PSA levels will exclude the possibility of extension of prostatic carcinoma into seminal vesicles. But even in high PSA levels, a diagnosis of amyloidosis cannot be ruled out as it is frequently seen coexisting with prostate and bladder cancer. Though imaging may help ascertain the origin of focal lesion to some extent, the definitive diagnosis is made on histopathological studies.

Teaching Point

Due to the considerable overlap between imaging features of seminal vesicle amyloidosis and of primary tumor/tumor invasion into the gland, TRUS guided biopsy should be considered in all masses involving the seminal vesicles wherein there is uncertainty about the origin and nature of mass.

Case 7.9

Brief Case Summary

34-year-old man with history of seminoma status post right orchiectomy.

Imaging Findings

Axial CT scan (Fig. 7.17) demonstrates a focal lesion in the right seminal vesicle with central hypodensity (arrow) and right inguinal lymph nodes with surrounding fat stranding in the right inguinal area (arrowhead). Biopsy of the right inguinal lymph node revealed metastasis from the testicular primary.

Fig. 7.17

Axial CT scan demonstrates a focal lesion in the right seminal vesicle with central hypodensity (arrow) and right inguinal lymph nodes with surrounding fat stranding in the right inguinal area (arrowhead). Biopsy of the right inguinal lymph node revealed metastasis from the testicular primary

Differential Diagnosis

Infiltrating carcinoma from adjacent organs like prostate, rectum and urinary bladder; seminal vesicle amyloidosis

Diagnosis and Discussion

Seminal Vesicle Neoplasms

Primary tumors of seminal vesicles are an extremely rare entity and metastasis are commoner than primary tumors. Reported benign tumors include cystadenoma, papillary adenoma, leiomyoma, epithelial stromal tumors, neurilemmoma and teratoma. Malignant tumors include adenocarcinoma (most common), leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, mullerian adeosarcoma like tumor, carcinoid, seminoma and cystosarcoma phylloides. There is no specific age limit with cases occurring in patients ranging from 19 to 90 years of age.

Clinical symptoms vary and can include hematuria, hemospermia, dysuria, difficult defecation and general pelvic pain.

Diagnosing seminal vesicle neoplasms is difficult as it may simulate a mass arising from adjacent pelvic structures such as the rectum, bladder and prostate with infiltration into the seminal vesicles. Tumor markers including prostatic specific antigen (PSA), prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP) and carcinogenic embryonic antigen (CEA) should be negative and can help exclude colorectal and prostatic tumors. Recently CA-125 and cytokeratin 7 positivity have been reported to assist in diagnosis with the former being used to assess response to therapy.

Dalgaard and Giertson proposed the following criteria for primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles:

(a)

The tumor should be a microscopically verified carcinoma, localized exclusively or mainly to the seminal vesicle.

(b)

The presence of other simultaneous primary carcinoma should be excluded.

(c)

The tumor should preferably resemble the architecture of the non-neoplastic seminal vesicle.

Diagnosis is based on clinical, radiological, and histological findings. On imaging, seminal vesicle masses are seen either as retrovesical masses with or without prostatic or urethral obstruction or as infiltrating seminal vesicle lesions with an enhancement pattern similar to advanced prostatic carcinoma.

Rectal ultrasound helps localize the tumor with the added benefit of obtaining biopsy specimens. On US, a cystadenoma may appear as a unilateral multiseptate cystic mass in a characteristic retrovesical location. Solid focal masses may appear mildly echogenic as compared to the rest of the normal parenchyma. Metastasis to seminal vesicles is seen as nonspecific soft tissue masses.

Cross sectional imaging with CT and MRI, in addition to localizing the tumor, also allows for exclusion of carcinoma of adjacent organs in early stages by demonstrating the epicenter of the mass. Also, CT and MR can accurate characterize lesions such as a teratoma which contains cystic and fatty components which can be readily characterized on both CT and MR. Primary adenocarcinoma of the seminal vesicles manifest as solid heterogeneous masses of intermediate signal intensity on T1 and hyperintense on T2. Few helpful imaging features point towards invasion of seminal vesicle rather than a primary tumor including obliteration of the angle between the seminal vesicle and prostate gland and loss of internal architecture of the gland. Rarely the only imaging features visualized may be focal enlargement or wall thickening of seminal vesicles. Metastasis to seminal vesicles are also seen as focal enlargement of the gland or as nonspecific a T2 hypointense soft tissue mass which cannot be differentiated from hemorrhage or radiation changes or senile amyloidosis and thus require a biopsy for definitive diagnosis.

Pitfalls

Primary tumors of seminal vesicle are difficult to differentiate from carcinoma originating in adjacent structures with secondary involvement of the seminal vesicles based only on imaging. Tumors of seminal vesicle origin are PSA, PAP and CEA negative whereas these markers are positive in prostatic and colorectal cancers. Primary tumors of seminal vesicle may show cytokeratin 7 and CA-125 positivity which is generally not seen in prostatic, bladder and rectal carcinomas. CK 20 positivity, seen in most rectal tumors, is not a feature of seminal vesicle tumor. A fair degree of overlap and inconsistencies in tumor markers may however still be seen. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of seminal vesicle may be indistinguishable from poorly differentiated prostate carcinoma and certain adenocarcinomas of urinary bladder.

The distinction from amyloidosis cannot be made on imaging alone in cases of localized masses and thus requires biopsy.

Teaching Points

Tumors of seminal vesicle are extremely rare with only about 50 cases reported in literature.

Immunohistochemistry may help in an otherwise difficult diagnostic dilemma with certain negative parameters helping in distinguishing carcinomas from adjacent structures.

Testis

Case 7.10

Brief Case Summary

38 year old male with absent left testicle on physical exam.

Imaging Findings

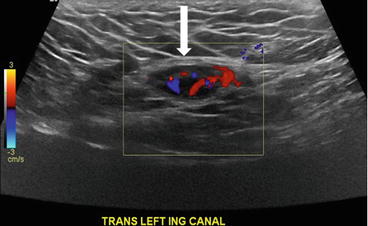

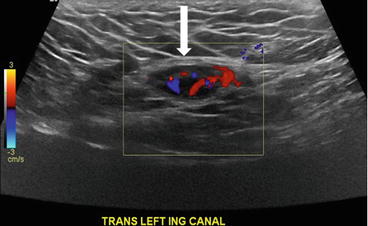

Gray scale transverse midline image of the scrotum demonstrates a normal right testicle (arrow, Fig. 7.18) with absence of the left testicle. Gray scale and color Doppler images of the left inguinal canal demonstrate the presence of an ovoid hypoechoic structure with internal vascularity, compatible with an undescended testicle (arrow, Figs. 7.19 and 7.20).

Fig. 7.18

Gray scale transverse midline image of the scrotum demonstrates a normal right testicle (arrow) with absence of the left testicle

Fig. 7.19

Gray scale image of the left inguinal canal demonstrate the presence of an ovoid hypoechoic structure with internal vascularity, compatible with an undescended testicle (arrow)

Fig. 7.20

Color Doppler image of the left inguinal canal demonstrate the presence of an ovoid hypoechoic structure with internal vascularity, compatible with an undescended testicle (arrow)

Differential Diagnosis

Left sided cryptorchidism, left inguinal canal lymph node

Diagnosis and Discussion

Left sided cryptorchidism

Cryptorchidism refers to an absence of testes within the scrotum which may be related to an absent testicle from agenesis or atrophy or may be related to failure of embryological descent from an intra-abdominal location. In addition, the terms retractile testes and ascending testes have been coined to refer to entities in which the normal testicle has been either pulled cephalad by the cremesteric reflex but remains reducible (retractile) or has ascended after a normal location in childhood without the ability to reduce into the scrotum (ascending).

Undescended testicles has higher incidence in premature infants and is most often unilateral with a predilection for the right side in approximately 70 % of cases. The etiology is likely multifactorial, although the most common cause is thought to be a defect in prenatal androgen secretion. The final diagnosis should not be made until at least 6 months of age as a small percentage of patients demonstrate gradual testicular descent during the first few months of life.

Imaging may be useful in locating the undescended testicle, though many feel that imaging studies should be bypassed in lieu of laparoscopic or inguinal exploration due to insufficient sensitivity. The most common location is within 2 cm of the internal inguinal ring. On ultrasound, the undescended testicle manifests as a round or oval hypoechoic structure between 7 and 15 mm in diameter. The detection of the mediastinum testis allows specific characterization of the mass as an undescended testicle. CT imaging has limited use in the evaluation of cryptorchidism and may demonstrate the presence of the spermatic cord leading to a mass in the inguinal canal. Despite the improved soft tissue contrast, MR imaging also has a limited role, with non-specific characteristics with the undescended testicle manifesting as an enhancing T1 hypointense mass with variable hyperintense T2 signal depending on the degree of atrophy.

Cryptorchidism is associated with infertility and a 4–7 fold increase in the risk for testicular cancer, with seminoma being the most common tumor. Other complications include an increased risk of torsion, trauma and inguinal hernia. Surgical treatment is the mainstay of therapy with orchiopexy as the treatment of choice for viable testes. If the testicle is non-viable, an orchiectomy is performed. Ascending testes are treated with orchiopexy while retractile testes require close clinical follow up.

Pitfalls

Lymph nodes may be impossible to differentiate from an atrophic testicle, though detection of the mediastinum testes confers more specificity. Overall, imaging plays a limited role, particularly in the setting of a non-palpable testicle. Laparoscopic or inguinal exploration is often the diagnostic and subsequent therapeutic treatment of choice.

Teaching Points

1.

Cryptorchidism refers to the absence of testes within the scrotum, one cause of which may be an undescended testicle. The most common location is within 2 cm of the internal inguinal ring.

2.

The role of imaging is limited in the evaluation of the undescended testicle, with laparoscopic or inguinal exploration usually preferred. US is the imaging modality of choice with the demonstration of the mediastinum testes specific for testicular tissue.

3.

Patients with undescended testicles are at an increased risk for infertility and neoplasm. Surgical treatment is the mainstay of therapy with orchiopexy as the treatment of choice for viable testes. If the testicle is non-viable, an orchiectomy is performed.

Case 7.11

Brief Case Summary

A 70 year old male with right sided testicular pain.

Imaging Findings

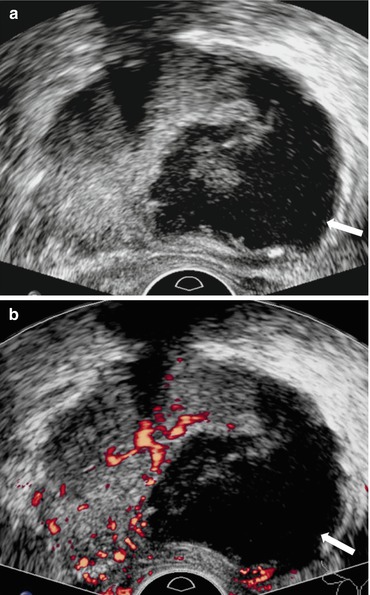

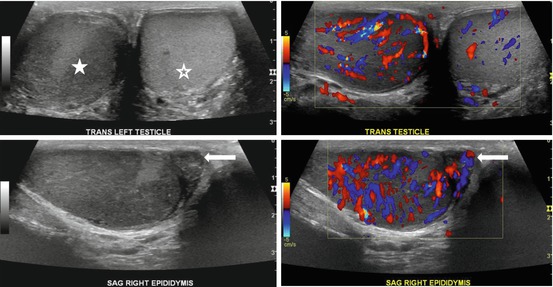

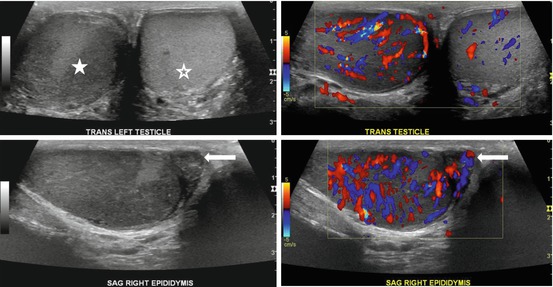

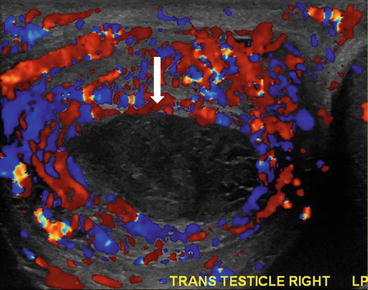

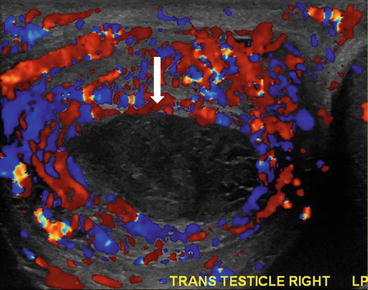

Gray scale image of the scrotum demonstrates an abnormal appearance of the right testicular parenchyma which is hypoechic (asterisk, Fig. 7.21a) with respect to the normal appearing left testicle (hollow asterisk, Fig. 7.21a). Color Doppler image demonstrates the presence of increased flow in the right testicle (Fig. 7.21b). Gray scale and color Doppler interrogation of the right epididymis demonstrates the presence of a heterogeneous and hypoechoic epididymis (arrow, Fig. 7.21c) with the presence of increased flow (arrow, Fig. 7.21d).

Fig. 7.21

Gray scale image of the scrotum demonstrates an abnormal appearance of the right testicular parenchyma which is hypoechoic (asterisk, a) with respect to the normal appearing left testicle (hollow asterisk, a). (b) Color Doppler image demonstrates the presence of increased flow in the right testicle. Gray scale and color Doppler interrogation of the right epididymis demonstrates the presence of a heterogeneous and hypoechoic epididymis (arrow, c) with the presence of increased flow (arrow, d)

Differential Diagnosis

Testicular torsion, orchitis, seminoma

Diagnosis and Discussion

Epididymo-orchitis

Epididymitis is the most common cause of acute scrotal pain in adolescents and men over the age of 35 years. The pathophysiology typically involves inflammation related to an ascending infection from the prostatic urethra and/or seminal vesicles, through hematogenous spread of infection has been reported. Spread to the testicle is commonly seen (referred to as epididymo-orchitis) occurring in 20–40 % of patients with epididymitis. The causative organism is typically bacterial with Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis occurring in sexually active males and Escherichia coli affecting young boys and elderly males. Cryptococcosis, tuberculosis and parasitic infections are infrequent etiologies. Non-infectious etiologies include sarcoidosis, Behcets disease and medications (such as amiodarone), though these are exceedingly rare. Patients typically present with fever and scrotal pain.

Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice, commonly demonstrating the presence of an enlarged, heterogeneous but predominately hypoechoic epididymis. The retrograde transmission of infection from the urinary tract results in initial involvement of the tail prior to the body and head of the epididymis. Spread to the testicle demonstrates similar findings on gray scale imaging. A reactive hydrocele is often present. Color evaluation demonstrates diffuse hyperemia of the inflamed tissue. If left untreated, epididymo-orchitis may be complicated by a pyocele or testicular abscess which manifests as an avascular hypo to anechoic mass with increased peripheral flow on color imaging.

Prognosis for both epididymitis and epididymo-orchitis is generally good, with most cases resolving with antibiotic therapy alone. The presence of an abscess may require surgical drainage.

Pitfalls

Epididymo-orchitis needs to be differentiated from testicular torsion as the latter requires prompt surgical treatment. On imaging testicular torsion demonstrates no flow, while hyperemia is present with epididymo-orchitis. Cases of torsion-detorsion may present with increased flow, although patients are typically pain free at the time of detorsion as opposed to epididymo-orchitis where the hyperemic testicle is associated with persistent scrotal pain. Isolated orchitis without involvement of the epididymis is not common, though can be seen in the clinical setting of mumps or HIV infection. On imaging, testicular neoplasms may present as vascular regions of decreased echogenicity, although clinically, they typically present as a painless, palpable mass.

Teaching Points

1.

Epididymitis is a common cause of testicular pain. In up to 40 % of patients the testicle may also be involved (epididymo-orchitis). Both conditions are conservatively managed with antibiotics and the presence of an abscess may require drainage.

2.

Retrograde transmission of a bacterial urinary tract infection is the most common cause. Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis are common organisms in sexually active males, while Escherichia coli is seen in young boys and elderly males.

3.

Sonography is the imaging modality of choice with findings demonstrating the presence of a heterogeneous, but predominately hypoechoic epididymis (and testicle in cases of epididymo-orchitis) associated with hyperemia.

4.

Torsion-detorsion or a testicular neoplasm may have a similar imaging appearance though patients are pain free at the time of hyperemia in the case of the former, while neoplasms typically present as a painless, palpable mass.

Case 7.12

Brief Case Summary

62 year old male with right testicular pain.

Imaging Findings

Ultrasound shows hypoechoic collection (arrow, Fig. 7.22) in the right scrotum inferior to the testis with scrotal thickening and hyperemia (Fig. 7.23) which could represent an abscess.

Fig. 7.22

Ultrasound shows hypoechoic collection (arrow) in the right scrotum inferior to the testis

Fig. 7.23

Image shows scrotal thickening and hyperemia, which could represent an abscess

Differential Diagnosis

Epididymo-ochitis, intratesticular/epididymal simple cysts, intratesticular spermatocele, tubular ectasia, epidermoid cyst, tunica albuginea cyst, intratesticular varicocele.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Testicular or epididymal abscess is an uncommon manifestation of severe or untreated epididymoorchitis and hence occurs typically in sexually active young adults. Rare causes include secondary bacterial infection of a hematoma or an intratesticular infarct.

The causative organisms are either sexually transmitted from Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis or from other sources like the urinary tract from Enterococcus spp., coliforms. Tuberculous etiology can be considered in endemic countries.

The patient presents with pain and swelling of the involved testis, with fever, often lasting for days. Tuberculous abscesses can be indolent. Examination may reveal a red, enlarged and tender hemiscrotum.

Grayscale and Doppler ultrasound is often the first and last modality to confirm the diagnosis. The abscess itself may be identified as are secondary findings including scrotal thickening and hyperemia. The abscess may be hypoechoic and well defined or an area of heterogeneously altered echotexture in the evolving stage. The abscess is avascular and can be intratesticular or epididymal. The surrounding inflammation or typical imaging signs of epididymo-orchitis including surrounding zone of increased vascularity, diffusely altered echotexture with increased vascularity in the testis and the epididymis, hydrocele/ pyocele and scrotal wall edema help to differentiate this lesion from its differential diagnoses.

CT or MRI do not have a role in the contemporary management of acute scrotum. In a rare instance of a complex abscess with perineal or pelvic extension, MRI may be useful for treatment planning. On MRI, the liquefied portion is hyperintense on T2 and hypointense on T1 with avid enhancement of the surrounding tissues and restricted diffusion.

The presence of long-term scrotal swelling without tenderness and a lower degree of blood flow in the peripheral portion of a large abscess are suggestive of tuberculous abscess.

Treatment of testicular/ epididymal abscess consists of appropriate antibiotics alone or with surgical drainage if necessary. Uncommonly, severe cases may necessitate orchiectomy. If medically managed, the abscess can be followed up on ultrasound for resolution.

Pitfalls

An evolving abscess can be difficult to differentiate from isolated epididymo-ochitis. Absence of vascularity in the index area may provide a clue; a follow up ultrasound may be performed in case of a doubt.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree