Chapter 2 Mammogram Interpretation

Breast Cancer Risk Factors

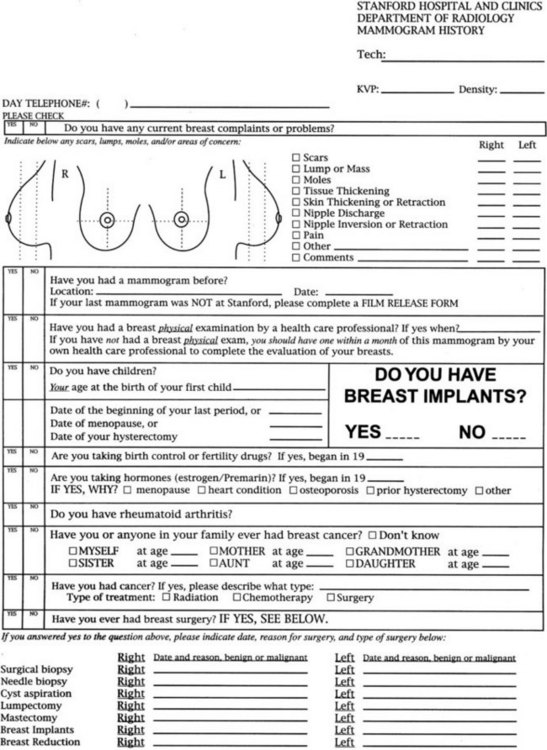

Risk factors for breast cancer are important to consider when reading mammograms, because they indicate a pretest probability of breast cancer. Compiling risk information on the breast history sheet provides the interpreting radiologist quick and easy-to-use access to this information (Fig. 2-1). Breast cancer risk factors are listed in Box 2-1. The most important risk factors are older age and female gender; U.S. statistics indicate that breast cancer will develop in one in eight women, if the women have a 90-year life span. Men also develop breast cancer, but only 1% of all breast cancers occur in men.

A family history of breast or ovarian cancer is a particularly important risk factor. The age, number, and cancer type in the affected relative is especially significant. Women with a first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or sister) with breast cancer have about double the risk of the general population and are at particularly high risk if that cancer was premenopausal or bilateral. If many relatives had breast or ovarian cancer, the woman may be a carrier of BRCA1 or BRCA2, the autosomal dominant breast cancer susceptibility genes. Genetic testing for these genes is possible. However, genetic testing is most appropriate when combined with the counseling, evaluation, and support provided by a genetic screening center because of the untoward social effects of positive (or negative) results. Carriers of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 on chromosome 17 have a breast cancer risk of 85% and an ovarian cancer risk of 63% by age 70. Women with BRCA2 on chromosome 15 have a high risk of breast cancer and a low risk of ovarian cancer. These genes account for 5% of all breast cancers in the United States and for 25% of breast cancers in women younger than age 30. Women of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish heritage have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer than does the general population (Box 2-2), but additional work is being done to determine whether this population has a higher rate of breast and ovarian cancer related to BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Other genetic syndromes that have a higher risk of breast cancer include the Li-Fraumeni, Cowden, and ataxia-telangiectasia syndromes.

Box 2-2 Family History Suggesting an Increased Risk of Breast Cancer

>2 relatives with breast or ovarian cancer

Breast cancer in relative age <50 years

Relatives with breast and ovarian cancer

Relatives with 2 independent breast cancers or breast plus ovarian cancer

Male relative with breast cancer

Family history of breast or ovarian cancer and Ashkenazi Jewish heritage

Signs and Symptoms of Breast Cancer

Women, or their partners, often find their own breast cancer by discovering a palpable hard breast lump. Breast lumps are a common symptom for which women seek advice (Box 2-3). Of particular concern are new, growing, or hard breast masses. Masses that are stuck to the skin or chest wall are particularly worrisome for an invasive breast cancer.

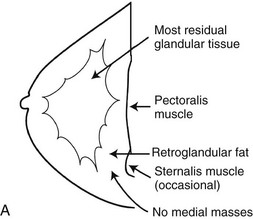

The Normal Mammogram

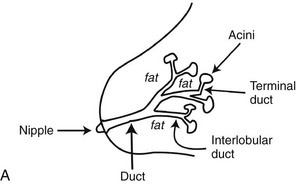

A normal breast is composed of a honeycomb supporting fibrous structure made up of Cooper ligaments that houses fatty tissue, which in turn supports the glandular elements of the breast (Fig. 2-2A). The glandular elements are composed of lactiferous ducts leading from the nipple and branching into excretory ducts, interlobular ducts, and terminal ducts leading to the acini that produce milk. The ducts are lined throughout their course by epithelium composed of an outer myoepithelial layer of cells and an inner secretory cell layer. The ducts and glandular tissue extend posteriorly in a fanlike distribution consisting of 15 to 20 lobes draining each of the lactiferous ducts, with most of the dense tissue found in the upper outer quadrant. Posterior to the glandular tissue is retroglandular fat, described by Dr. Laszlo Tabar as a “no man’s land,” in which no glandular tissue should be seen. The pectoralis muscle lies behind the fat on top of the chest wall.

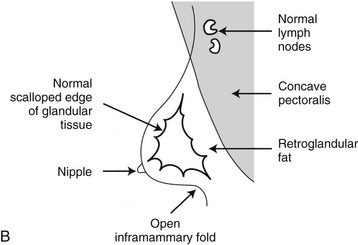

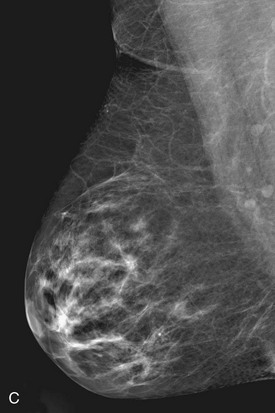

On the normal mediolateral oblique (MLO) mammogram, the pectoralis muscle is a concave structure posterior to the retroglandular fat near the chest wall. Normal lymph nodes high in the axilla overlie the pectoralis muscle (see Fig. 2-2B and C). Normal lymph nodes are sharply marginated, oval, or lobulated dense masses with a radiolucent fatty hilum. They are commonly found in the upper outer quadrant of the breast along blood vessels. Lymph nodes also occur normally within the breast and are known as normal “intramammary” lymph nodes. If the lymph node has the typical kidney bean shape and a fatty hilum, it should be left alone. If one is uncertain about whether a mass represents an intramammary lymph node, mammographic magnification views may help display the fatty hilum, or ultrasound may show the typical hypoechoic appearance of the lymph node and the echogenic fatty hilum.

Usually fibroglandular tissue occurs symmetrically in the upper outer quadrants of the breasts. The breast tissue is usually distributed fairly symmetrically from left to right. When viewing mammograms, the clinician should place the mammograms back to back so that the chest walls face each other for easy viewing of tissue symmetry (see Fig. 2-5A). Fatty tissue surrounds the glandular tissue.

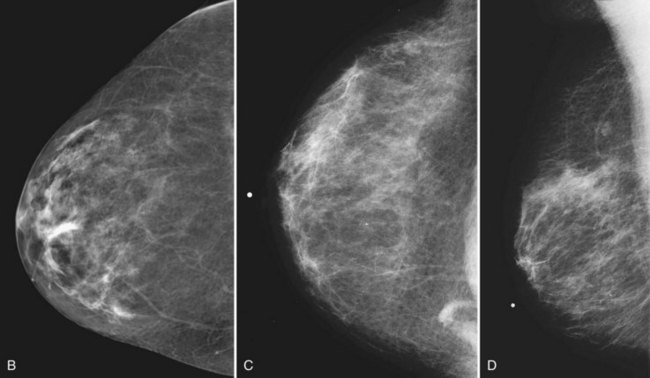

On the normal craniocaudal (CC) projection, the pectoralis muscle produces a half-moon–shaped density near the chest wall (Fig. 2-3A and B). Fat lies anterior to the muscle, and the white glandular tissue lies anterior to the fat. In older women, most of the glandular tissue in the medial breast undergoes fatty involution, and therefore most of the residual dense glandular tissue exists in the upper outer breast.

There should be only fatty tissue in the medial breast near the chest wall. The only normal exception is the sternalis muscle, a muscular density near the medial aspect of the chest wall that should not be mistaken for a mass (see Fig. 2-3C and D). If there is a question that the density is a mass instead of the sternalis muscle, a cleavage view (CV) mammogram or ultrasound can prove that the density is a muscle and a normal structure.

The American College of Radiology’s (ACR) Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) lexicon separates breast density into quartiles depending on how much glandular tissue the breast contains by volume. “Dense” contains the most white (>75% dense), “heterogeneously dense” is less white (50–75% dense), “scattered fibroglandular” is even less white (25–50%), and “fatty” is the least white (<25% dense) (Box 2-4). A “dense” breast does not mean the breast is hard to the touch. Breast density has little correlation to how hard or soft the breast feels on physical examination; that is, you cannot predict how soft a breast will feel by looking at the mammogram. Radiologists describe breast density in the mammogram report so that referring doctors will know how white the breast looks and how confident the radiologist is in excluding cancer.

Box 2-4

ACR BI-RADS® Terms for Breast Density

The breast is almost entirely fat (<25% glandular).

There are scattered fibroglandular densities (approximately 25–50% glandular).

The breast tissue is heterogeneously dense, which could obscure detection of small masses (approximately 51–75% glandular).

From American College of Radiology: ACR BI-RADS®—mammography, ed 4, In ACR Breast Imaging and Reporting and Data System, breast imaging atlas, Reston, VA, 2003, American College of Radiology.

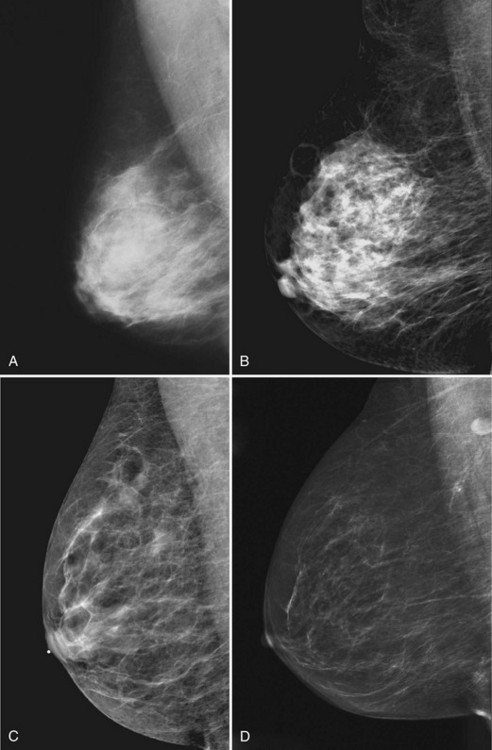

Young women have mostly glandular breasts, and their mammograms are described as “dense.” As women age, the fibroglandular tissue involutes into fat, which is black. The natural progression of the mammogram is mostly white (dense) at a young age when the breasts are filled with glandular tissue, becoming progressively darker as the woman ages and her glandular tissue turns into fat. The amount of remaining glandular tissue varies from woman to woman. Some older women have surprisingly large amounts of dense white tissue on the mammogram; the amount remaining depends on genetics, parity, and exogenous hormone replacement therapy. But generally as women age, the glandular tissue involutes so that there are relatively greater amounts of dense glandular tissue remaining in the upper outer quadrant of the breast and darker fatty areas in the medial and lower part of the breast. In some women, only fatty tissue is left after the menopause (Fig. 2-4).

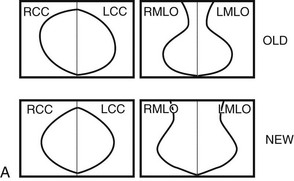

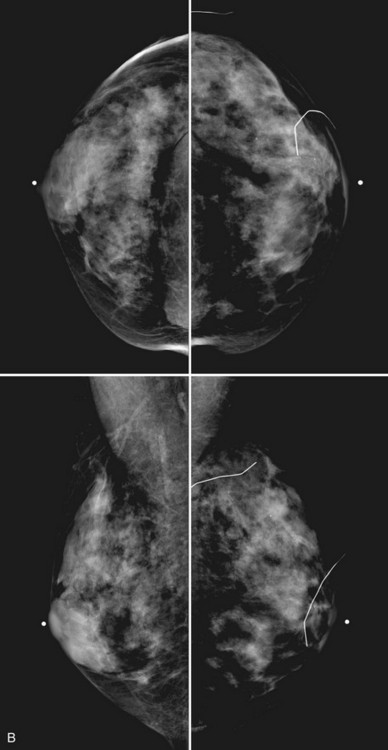

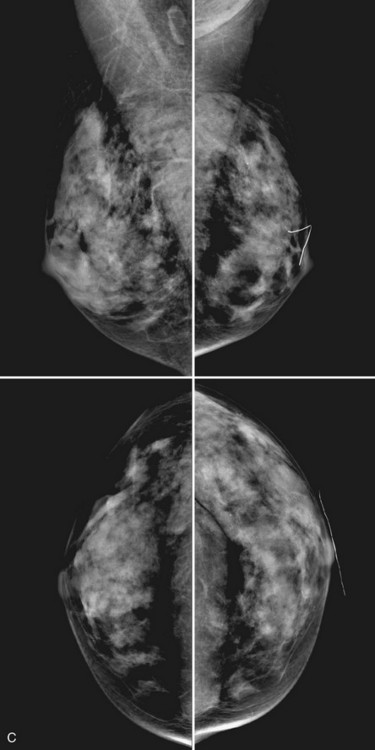

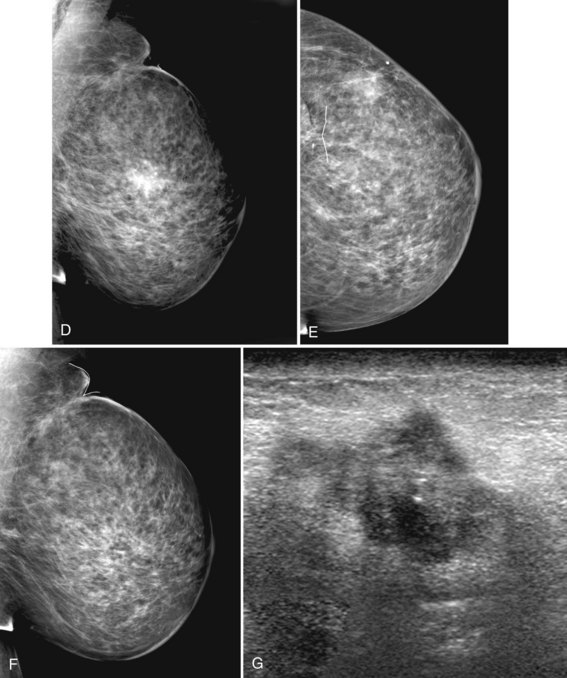

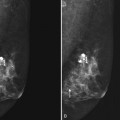

Breast tissue is usually symmetric, or “mirror image,” when comparing left to right mammograms, although 3% of women have normal asymmetric glandular tissue. Normal asymmetric glandular tissue is a larger volume of normal fibroglandular tissue in one breast than in the other, but with one breast not necessarily being larger than the other. One method of evaluating for symmetry is to view the left and right MLO mammograms back to back and the CC mammograms back to back. The glandular tissue pattern is usually fairly symmetric from side to side, and asymmetries are easily identified using this technique (Fig. 2-5A to C).

A normal mammogram does not usually change from year to year after taking into account the normal involution of glandular tissue over time. Because the mammogram stays the same from year to year, comparing old studies with current studies makes it easier to see new or developing changes. For this reason, older films of good quality are placed next to the new films to look for subtle change (see Fig 2-5D to H). Because subtle changes may take longer than a year to become evident, one should compare both last year’s films and films more than 2 years old (or the oldest films of comparable quality) to the new ones. If the mammograms are screen-film studies, the images are viewed on a high-intensity view box with the light parts of the films masked to block extraneous light. For full-field digital mammograms (FFDMs) viewed on soft copy, the images are displayed on high-resolution bright monitors in a dark room with little to no ambient light, comparing old mammograms to new ones in the display protocol.

Mammographic Findings of Breast Cancer

Mammographic detection of breast cancer depends on the sensitivity of the test, the experience of the radiologist, the morphologic appearance of the tumor, and the background on which it is displayed. Cause for a “missed” breast cancer can usually be traced to one of these factors (Table 2-1).

Table 2-1 Reasons for Missed Cancers

| Errors in technique | |

| Errors in detection | |

| Errors in interpretation | Radiologist sees and perceives finding, incorrectly interprets finding as nonactionable |

| Tumor morphology | Tumor shape similar to background fibroglandular tissue displayed on the mammogram |

| True negative study | Tumor cannot be seen even in retrospect |

Radiologists see breast cancers on screening mammography because they see pleomorphic calcifications or spiculations produced by the tumor. Radiologists also may see architectural distortion, asymmetric density, a developing density, a round mass, breast edema, lymphadenopathy, or a single dilated duct, which are the other mammographic signs of breast cancer. The radiologist has to not only see the finding, but to also recognize that the finding is abnormal and correctly interpret the study as needing further action (i.e., is “actionable”) (Box 2-5).

The mammographic signs of breast cancer listed in Table 2-2 are discussed in further detail in Chapter 3 on breast calcifications, Chapter 4 on breast masses, and Chapter 10 on clinical problems. The trick is to see the cancer, perceive it and have it register in one’s mind, then interpret the findings correctly and act on the finding.

Table 2-2 Mammographic Findings of Breast Cancer

| Finding | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Pleomorphic calcifications | Cancer (most common), benign disease, fat necrosis |

| Spiculated mass | Cancer, postsurgical scar, radial scar, fat necrosis |

| Round mass | Cyst, fibroadenoma, cancer, papilloma, metastasis |

| Architectural distortion | Postsurgical scarring, cancer |

| Developing density | Cancer, hormone effect, focal fibrosis |

| Asymmetry: focal or global | Normal asymmetric tissue (3%), cancer (suspicious: new, palpable, a mass containing suspicious calcifications or spiculation) |

| Breast edema | |

| Lymphadenopathy | |

| Single dilated duct | Normal variant, papilloma, cancer |

| Mass with calcifications | Cancer, fibroadenoma, papilloma; exclude calcifying oil cyst |

| Nothing | 10% of all cancers are false-negative on mammography |

An Approach to the Mammogram

Many tools are available to help the radiologist correctly interpret mammograms (Table 2-3). The first is the breast history and physical findings. The breast history sheet alerts the radiologist to the patient’s risk factors for cancer and the patient’s pretest probability of cancer (see Fig. 2-1). The history sheet includes the patient’s clinical history of breast biopsies and a schematic diagram of their location so that old scars are not misinterpreted as cancer.

Table 2-3 Tools Used for Interpretation of Mammograms

| Tool | Use |

|---|---|

| Breast history, risk factors | Evaluate patient’s complaint and risks |

| Technologist’s marks | Show skin lesions, scars, problem areas |

| Putting images back to back | |

| Bright light (SFM) | View skin, dark parts of film |

| Window/level (FFDM) | Contrast for masses, calcifications |

| Magnifying lens or magnifier | Visualize mass borders, calcifications |

| Old films | Compare for changes |

| CAD (if available) | Look for CAD marks after initial interpretation |

CAD, computer-aided detection; FFDM, full-field digital mammogram; SFM, screen-film mammogram.

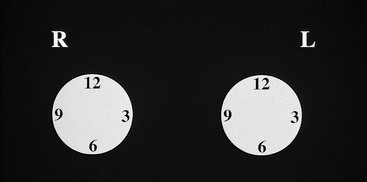

A technologist or aide usually interviews the patient, marking the location of any palpable finding on a diagram on the history sheet. Positions of findings in the breast are described in breast quadrants, with the upper outer quadrant representing the breast quadrant nearest the axilla. Another way to describe a breast location is by using the “clock face” method, in which the location of breast findings is described as though a clock were superimposed on each breast as the woman faces the examiner (Fig. 2-6). This means that the upper outer quadrant in the right breast is between the 9- and 12-o’clock positions, but the upper outer quadrant in the left breast is between the 12- and 3-o’clock positions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree