Chapter 4 Mammographic and Ultrasound Analysis of Breast Masses

Mammographic Technique and Analysis

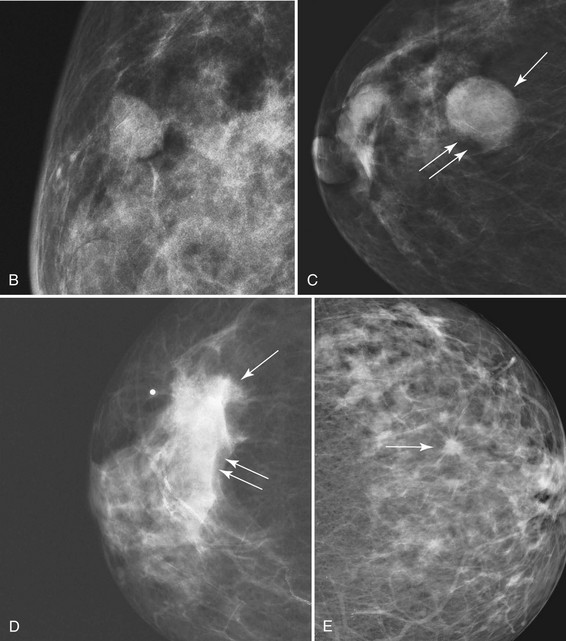

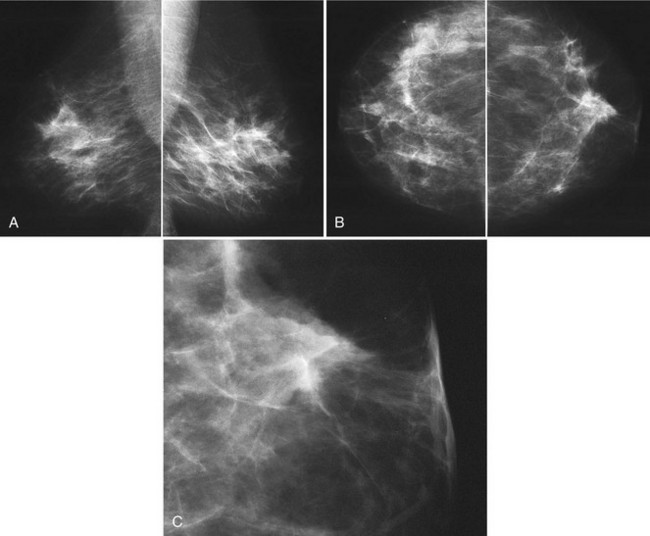

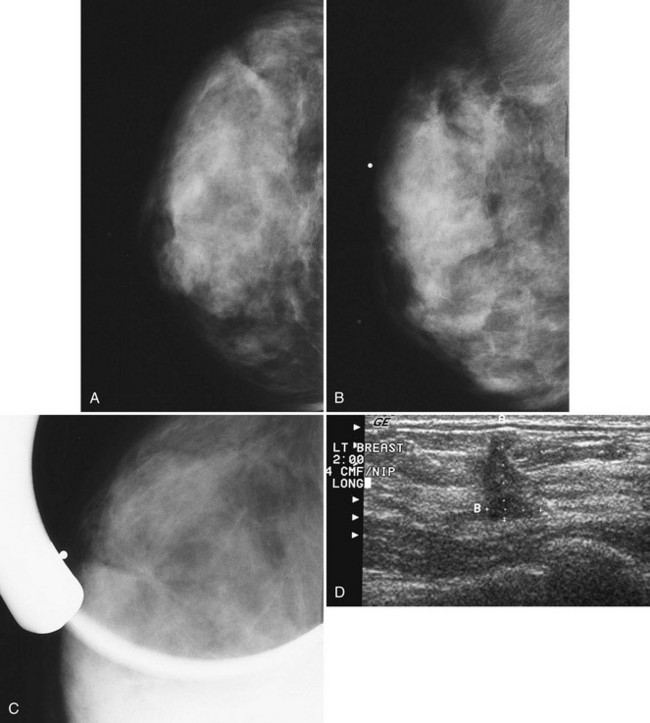

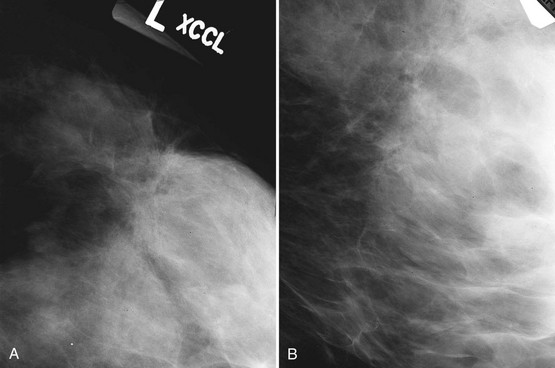

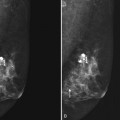

The ACR BI-RADS® lexicon (Table 4-1) defines mass shapes as round, oval, lobular, or irregular. As the mass shape becomes more irregular, the probability of cancer increases (Fig. 4-1A).

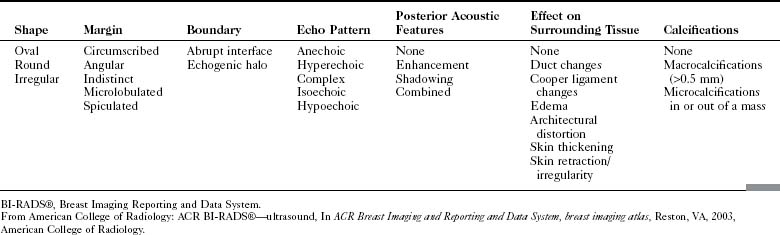

Table 4-1 American College of Radiology BI-RADS® Mass Descriptors

| Shape | Margin | Density |

|---|---|---|

BI-RADS®, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System.

From American College of Radiology: ACR BI-RADS®—mammography, ed 4, In ACR Breast Imaging and Reporting and Data System, breast imaging atlas, Reston, VA, 2003, American College of Radiology.

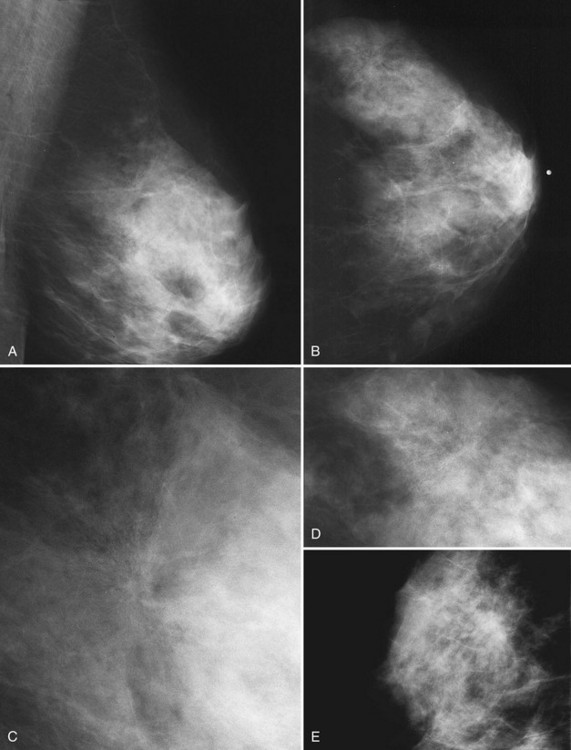

The ACR BI-RADS® lexicon describes mass margins as circumscribed (well-defined or sharply defined), microlobulated, obscured by surrounding glandular tissue, indistinct, or spiculated (see Fig. 4-1B to E). As with mass shape, as the mass margin becomes more spiculated the probability of cancer increases. Masses with well-circumscribed borders are likely to be benign, and less than 10% of cancers are smooth. Microlobulated masses have small undulations, like petals on a flower, and are more worrisome for cancer than are smooth masses. An obscured mass has a border hidden by overlapping adjacent fibroglandular tissue; as a result, that border cannot be assessed. An indistinct mass is worrisome for carcinoma because it suggests that the surrounding glandular tissue is infiltrated by malignancy. Finally, spiculated masses are characterized by thin lines radiating from the central portion of the mass and are especially worrisome for cancer. When caused by cancer, spiculations are due to productive tumor fibrosis or growth of tumor into the surrounding glandular tissue.

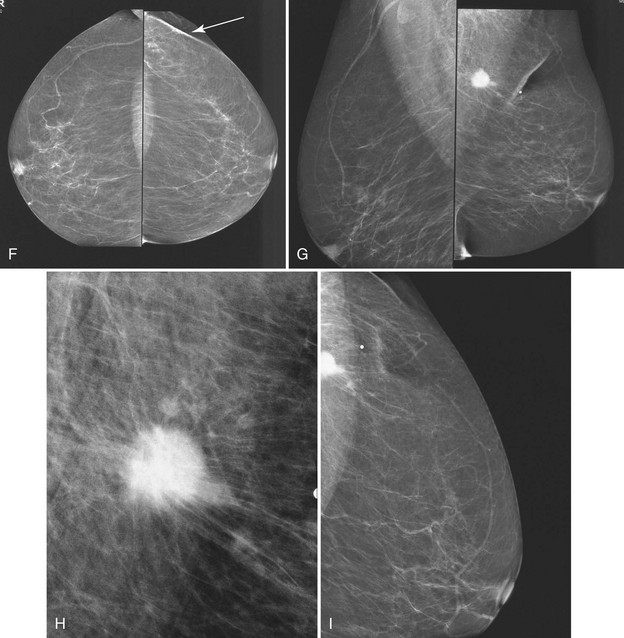

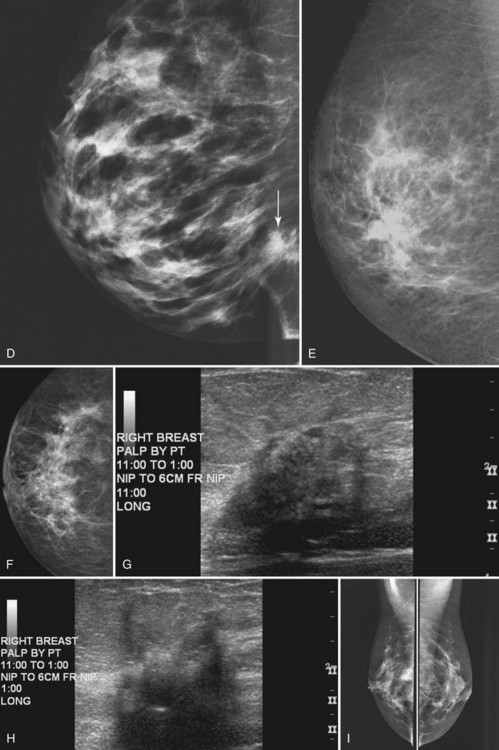

Masses can have associated findings that can indicate cancer (listed in Box 4-1). Associated findings worrisome for cancer include skin or nipple retraction, skin or trabecular thickening, axillary adenopathy, architectural distortion, and calcifications (see Fig. 4-1F to I).

Box 4-1

American College of Radiology BI-RADS® Associated Findings

BI-RADS®, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System.

From American College of Radiology: ACR BI-RADS®—mammography, ed 4, In ACR Breast Imaging and Reporting and Data System, breast imaging atlas, Reston, VA, 2003, American College of Radiology.

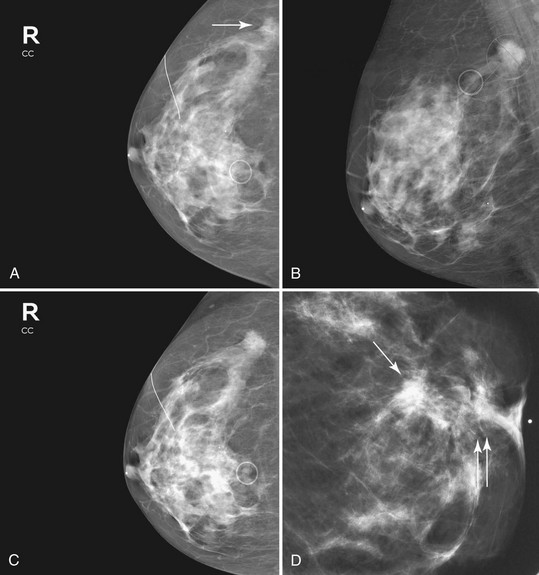

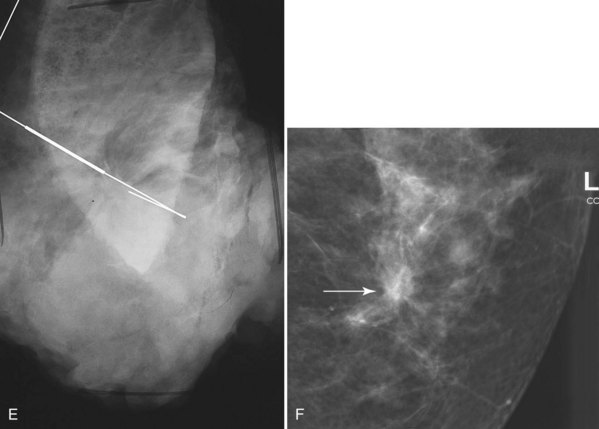

Associated calcifications in or around a suspicious mass are important for two reasons. If the mass is cancer, calcifications around it may represent ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Subsequent excisional biopsy must remove both the mass and all surrounding suspicious calcifications to excise the entire malignancy (Box 4-2). Knowing the extent of the suspicious calcifications helps the surgeon plan the excision (Fig. 4-2). Second, suspicious calcifications inside a mass may be the only clue that the mass is a cancer.

Ultrasound Technique and Analysis of Masses

The ACR BI-RADS® ultrasound lexicon describes terms and features of breast masses that are key for the diagnosis of cancer (Table 4-2). Stavros and colleagues established another set of terms that are often used in evaluating breast masses (Box 4-3). Illustrations of these features are shown in Chapter 5.

Box 4-3

Ultrasound Features of Solid Breast Masses

From Stavros AT, Thickman D, Rapp CL, et al: Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions, Radiology 196:123–134, 1995.

After scanning, the technologist takes representative pictures of the mass and labels the images to clarify the mass’s location in the breast. This makes the mass easier to find on repeat ultrasound examinations. Ultrasound labeling includes which breast was scanned (left or right), position of the mass in terms of breast clock face or quadrant, location in centimeters from the nipple, scan angle (radial or antiradial, transverse or longitudinal), and the technologist’s initials. The technologist captures the image without and with measuring calipers on the muscle (Box 4-4). It is also helpful to indicate whether the mass is palpable or nonpalpable.

Correlating Palpable and Nonpalpable Masses on Mammography and Ultrasound

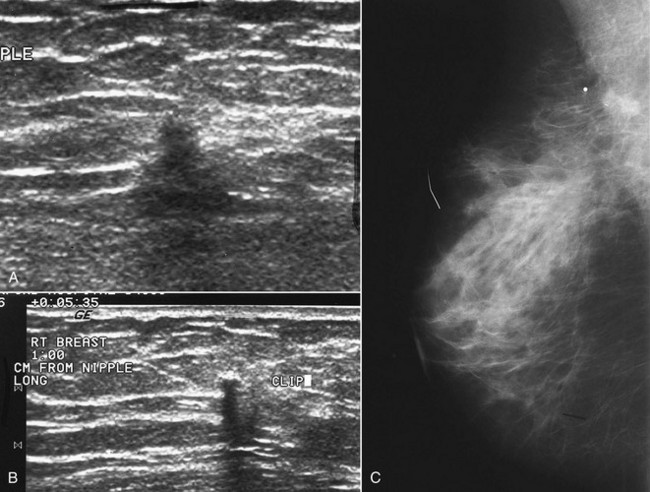

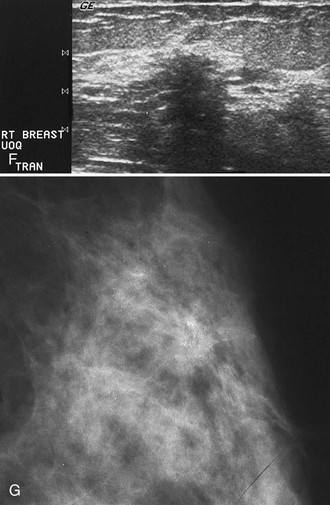

Sometimes it is still uncertain whether an ultrasound and mammographic finding are one and the same. If the patient agrees to a biopsy of the ultrasound finding, the radiologist places a metallic marker into the mass using an ultrasound-guided, percutaneously placed needle after the biopsy (Fig. 4-3). Repeat mammograms should show the marker in the mass if the two findings are the same. Alternatively, a retractable hookwire may be placed in the mass. A mammogram with the wire in place will show that the ultrasound finding and the mammographic finding represent the same mass. The radiologist can subsequently remove the retractable hookwire.

The mammography and ultrasound report for a breast mass should describe if the mass is palpable; the size, shape, margin, and density of the mass; its location and associated findings; and any change from previous examinations, if known. The report should also include ultrasound finding descriptors and whether it correlates with the mammographic finding. Finally, each report that includes a mammogram should be assigned an ACR BI-RADS® final assessment code indicating the level of suspicion for cancer and follow-up management recommendations (Box 4-5).

Box 4-5

American College of Radiology BI-RADS® Mass Reporting

BI-RADS®, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System.

From American College of Radiology: ACR BI-RADS®—mammography, ed 4, In ACR Breast Imaging and Reporting and Data System, breast imaging atlas, Reston, VA, 2003, American College of Radiology.

Masses with Spiculated Borders and Sclerosing Features (Box 4-6)

Cancer

Invasive Ductal Cancer

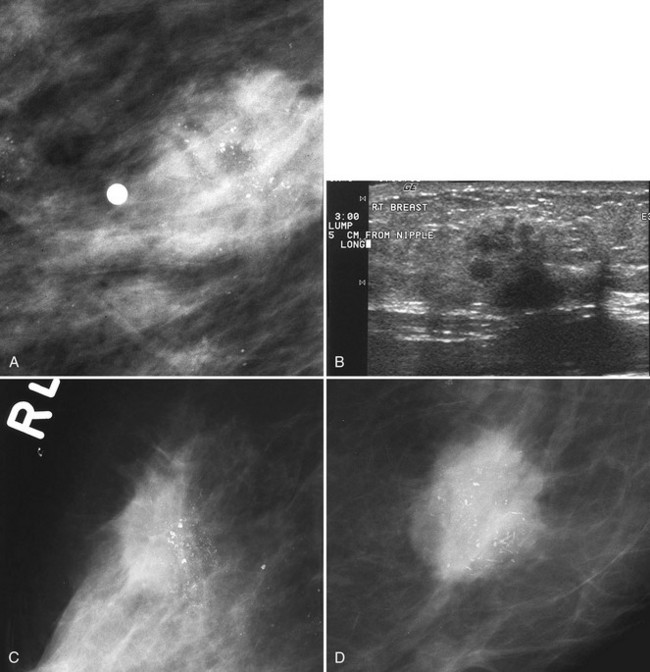

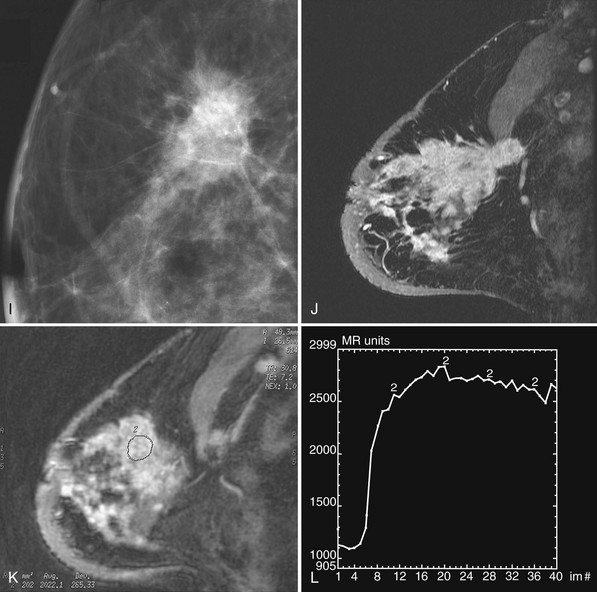

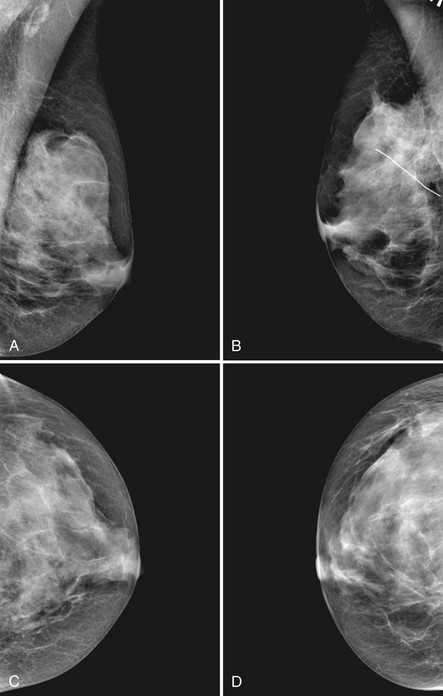

Invasive ductal carcinoma is the most common breast cancer and accounts for approximately 90% of all cancers. Also known as invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), invasive ductal cancer usually grows as a hard irregular mass in the breast (Fig. 4-4). The classic appearance of invasive ductal cancer is a dense irregular or spiculated mass, occasionally containing pleomorphic calcifications or having adjacent pleomorphic calcifications representing DCIS. On the mammogram, the mass should be about the same size and density on two orthogonal mammographic views. Spot compression magnification views may show unsuspected calcifications in or around the mass or unsuspected irregular borders.

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma

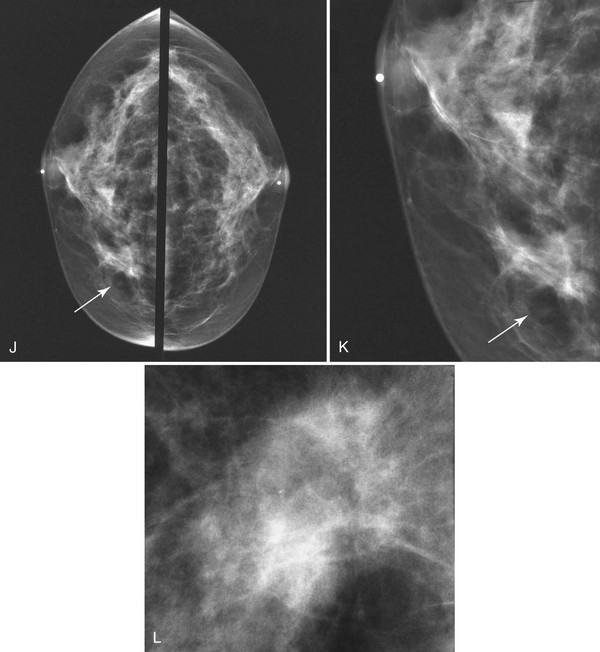

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is most commonly seen as an equal- or high-density noncalcified mass, occasionally showing spiculations or ill-defined borders. ILC has a higher rate of bilaterality and multifocality than does invasive ductal cancer. ILC accounts for less than 10% of all invasive cancers, but historically is the most difficult breast cancer to see on mammograms (Box 4-7). ILC is the cancer that gives radiologists a bad name because it can be missed by mammography, at a rate reported by Brem and colleagues to be as high as 21%. This failure can be partly explained by the growth pattern of the carcinoma. Classically, ILC grows in single lines of tumor cells infiltrating the surrounding glandular tissue and may not produce a mass, making it difficult to see by mammography and difficult to feel by physical examination. ILC usually does not contain microcalcifications. It infiltrates the breast, is often seen on only one view, and may cause subtle distortion of the surrounding glandular tissue. When actually seen on the mammogram, ILC masses are often of equal or higher density than fibroglandular tissue and are seen because of the mass itself or its effect on surrounding tissue, such as architectural distortion and straightening of Cooper ligaments. As with any mass, distortion and tenting of glandular tissue caused by ILC are most easily seen in locations where Cooper ligaments extend out into surrounding fat, such as in the retroglandular fat or along the edge of the normal, scalloped fibroglandular tissue (Fig. 4-5).

Tubular Cancer

Tubular carcinoma is a generally slow-growing tumor with a bilateral incidence of 12% to 40%. On mammography, tubular cancer is a dense or equal-density spiculated mass with occasional microcalcifications. On occasion it may be apparent on the previous mammogram because of its slow growth. Although controversial, some pathologists believe that radial scars may be a precursor to tubular carcinoma. In general, tubular carcinoma has a good prognosis and a lower incidence of metastases than does invasive ductal cancer. On ultrasound, tubular cancers are hypoechoic, irregular masses that occasionally produce acoustic shadowing (Fig. 4-6).

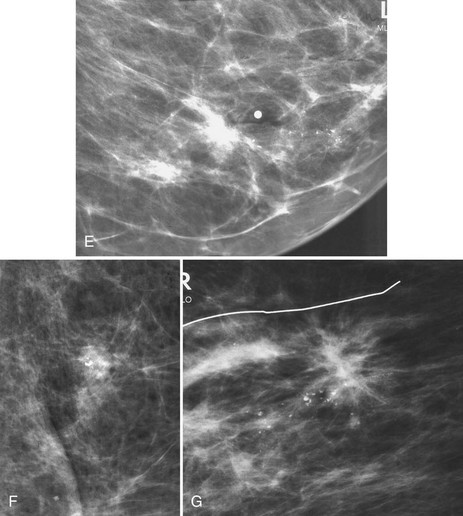

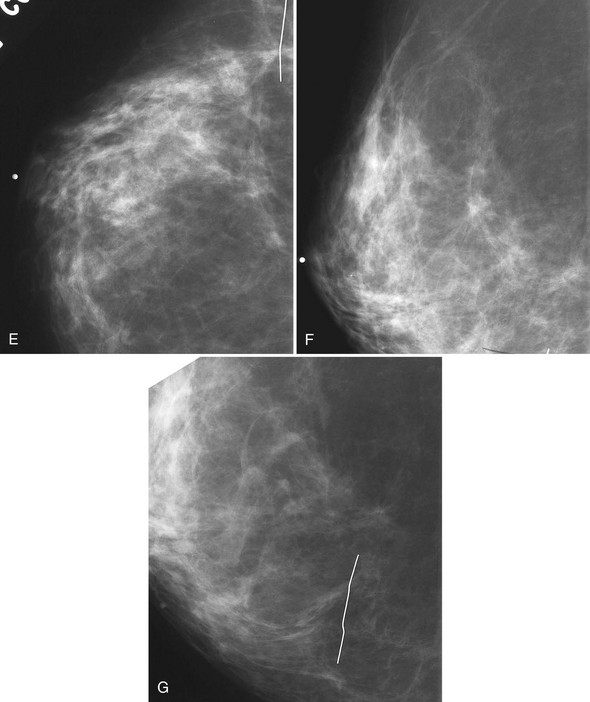

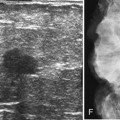

Postbiopsy Scar

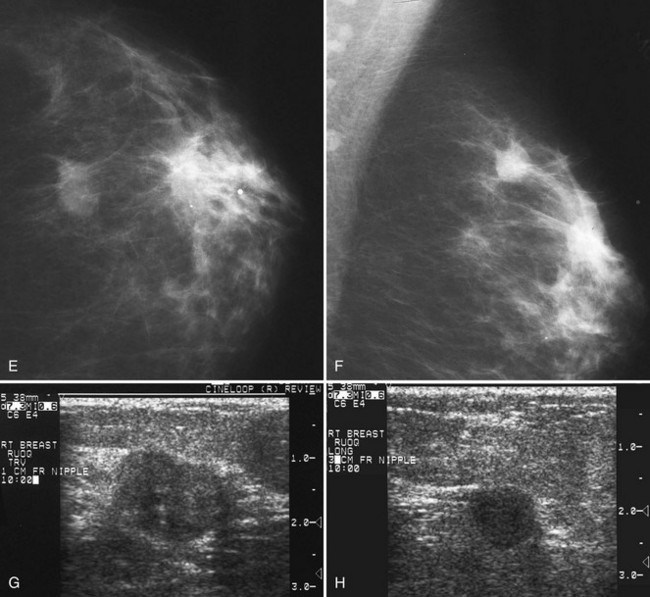

The scar is not of concern for cancer if it occupies a surgical site (Box 4-8). To distinguish postbiopsy scars from cancer, the radiologist looks at the previous biopsy locations on the breast history form and reviews older films to see if the “scar” is at the same location. Some facilities place a radiopaque linear metallic scar marker on the patient’s skin scar to show the location on the mammogram (Fig. 4-7A to D). The metallic linear scar marker should be on top of the “scar” (see Fig. 4-7E and F). If the “scar” does not correspond to a postbiopsy site, it is not a scar. Because spiculated masses may represent cancer, they should be considered suspicious and should undergo biopsy.

Fat Necrosis, Sclerosing Adenosis, and Other Benign Breast Disease

Both sclerosing adenosis and proliferative fibrocystic change may have a slightly spiculated appearance on mammography; they occasionally also contain calcifications and can simulate cancer. When spiculated and associated with calcifications, fat necrosis, sclerosing adenosis and proliferative fibrocystic disease undergo biopsy and are a cause of false-positive biopsies (Fig. 4-8).

Radial Scar

On mammography, a radial scar appears as a spiculated mass with either a dark or white central area that may or may not have associated microcalcifications (Fig. 4-9). It is a myth that radial scars have dark centers in the mass on mammography (Fig. 4-10) and can be distinguished from breast cancers, which have white-centered masses. Scientific studies have shown that radial scars and breast cancer can both have either white or dark centers on mammograms. This means that all spiculated masses not representing a postbiopsy scar should be sampled histologically (Box 4-9). On ultrasound, a radial scar is a hypoechoic mass, with or without acoustic shadowing.