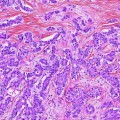

Fig. 1

Five-year survival for gallbladder cancer generated from surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) database [4]

Gallstones and chronic gallbladder inflammation are two important risk factors for development of GB cancer. Cholelithiasis is an associated finding in the majority of cases, but less than 1 % of patients with cholelithiasis develop cancer. Stones larger than 3 cm are associated with a tenfold increased risk of cancer [5]. Porcelain GB was once suspected to be a risk factor for development of GB cancer, but recently this relationship has been questioned. Towfigh et al. [6] evaluated the pathology of 10,741 GB specimens between the years 1955 and 1998 and identified fifteen porcelain GB, and none had cancer. Similarly, Khan et al. analyzed 1,200 cholecystectomies and identified 13 patients with porcelain GB, and all were benign. They concluded that prophylactic cholecystectomy is not indicated for porcelain GB for risk of development of later cancer.

The most common symptoms caused by GB cancer are jaundice, pain, and fever. These symptoms are common for both benign and malignant diseases and that is a key reason for delay in diagnosis. Any GB mass or polyp found on imaging should lead to a high degree of suspicion for early cancer. Ninety percentage of primary GB cancers are adenocarcinomas, and they originate from the fundus (60 %), body (30 %) and neck (10 %). Among the morphological types, the papillary growth pattern seems to have better prognosis as this subtype tends to have little invasion. In contrast, the infiltrative pattern seems to invade early and grow along the subserosal plane (plane of dissection during simple cholecystectomy). The third morphological pattern is the nodular type, which shows early invasion, but the margins seem to be well defined; hence, they tend to have a better prognosis.

2.1 History of Biliary Surgery

Early part of the eighteenth century was the beginning of surgery for biliary diseases. In 1743, Jean Louis Petit, Paris, coined the term “biliary colic” (“colique hepatique”). He presented his seminal paper at the Paris Surgical Academy entitled “Considerations Concerning Tumors Produced by Retained Bile in the Gallbladder….” [7]. In the United States, John Bobbs [8] is credited with the first cholecystostomy in Indianapolis in 1867. A decade later in 1878, Theodore Kocher in Berne, Switzerland, who was trained under Billroth and Langenbuch did his cholecystostomy in two stages [9]. The Kocher maneuver named was first used for gastric surgery, and only later utilized for biliary surgery by Vautrin. Kocher also pioneered internal choledochoduodenostomy to remove common bile duct calculi. Along with Dr. Matti, he wrote the book Hundert Operationen an den Gallenwegen (A hundred operations on the bile ducts). Carl Langenbuch of Germany is credited with performing the first cholecystectomy at the Lazarus Hospital in Berlin in July, 1882 [10]. George Pack in 1955 was the first to report 3 cases, where radical liver resection (right hepatic lobectomy) along with portal lymph node dissection was performed for the treatment of gallbladder cancer [11].

Toward the end of the twentieth century in 1985, Prof Dr Med Erich Muhe of Böblingen, Germany, did the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy [12]. Since then it has become the gold standard for removal of gallbladder for benign disease. At present, surgeons use other minimally invasive techniques to remove the gallbladder [13, 14]. Biliary surgery continues to evolve with the help of advancements in imaging with ultrasound in liver and biliary surgery [15], computerized tomography (CT) scan of the liver [16] and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging [17]. After popularization of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, there is a new presentation of gallbladder cancer, namely after minimally invasive cholecystectomy. The number of incidental cancers detected in the pathology specimen is approximately one for every hundred gallbladders that are removed for a presumed benign etiology [7].

2.2 Surgical Anatomy

Anatomically, the gallbladder lies in the subhepatic area close to Couinaud’s liver segments 4b and 5. The GB wall is composed of an innermost layer of mucosa which is lined by simple columnar epithelium; beneath this is a layer of lamina propria. The GB wall lacks submucosa. A layer of muscular tissue (smooth muscle) is present beneath the lamina propria. The outermost layer is made up of thick connective tissue called adventitia which is present in the area where GB is attached to the liver tissue (GB bed). In the unattached area, facing the free peritoneal cavity, there is an outer layer of mesothelium and loose connective tissue called serosa. The subserosal plane is the least bloody plane of dissection during routine cholecystectomy. The cystic plate is the gallbladder serosa on the liver which is usually left behind after dissection in the subserosal plane. According to American Joint Committee on Cancer staging, the lymph nodal station N1 is defined as regional (hepatic hilus) which corresponds to nodes around cystic duct, common hepatic duct, portal vein and hepatic artery. N2 station refers to metastases nodes around celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery, periduodenal and peripancreatic nodes.

GB cancers spread by direct extension to contiguous structures or via veins draining segments IV and V to the liver. GB cancer can also spread to regional lymph nodes and to the peritoneal cavity by direct extension or after bile spillage. In addition, GB cancer has a propensity to seed and grow along needle track sites, including port sites. GB cancers very rarely metastasize via blood stream.

3 Presentation

There are three common presentations of GB cancer. The most common is a presentation as incidental gallbladder cancer. As such, it may be (a) detected during surgery (cholecystectomy) or (b) detected on postoperative pathology review of the resected gallbladder specimen. Gallbladder cancer can also be detected as a large invasive mass in GB fossa detected on imaging. Finally, it may be detected as a small mass or polyp in the GB found on preoperative imaging. These presentations will be discussed separately.

1.

Management of incidental gallbladder cancer (IGBC)

IGBC refers to GB cancer discovered incidentally at the time of surgery (cholecystectomy) or detected postoperatively in the GB specimen removed for a presumed benign pathology.

a.

Intraoperative detection

Since the liberal use of laparoscopic technology for cholecystectomies in the early 1990s, there is increased detection of GB cancers. In a study by [18], almost 50 % of the cancers were discovered incidentally. If suspicion of gallbladder cancer arises during initial laparoscopic surgery for presumed gallstone disease or cholecystitis, intraoperative staging should be done. Metastatic disease should be ruled out by sending frozen section on any suspected lesion or lymph node. A thorough laparoscopic examination of the abdominal cavity should be done. The exploration should include inspection of the liver, including intraoperative ultrasound, gastrohepatic ligament, porta hepatis, pelvis and peritoneal cavity. Additionally, frozen section of the gallbladder should be sent when the diagnosis is in doubt, after resection, and to confirm negative margins. In one study, frozen section biopsy had an accuracy of 88 % [19] and sensitivity and specificity of over 90 and 100 %, respectively [20]. However, the accuracy of T stage which is critical for management though is less than 100 % [20].

If frozen section confirms GB malignancy and the lesion is resectable, then an extended cholecystectomy should be performed after conversion to an open procedure [21]. If expertise is not available, then surgery should be deferred. The patient should then be transferred to an experienced center. Such approach is reasonable and does not affect the prognosis [22, 23].

b.

Cancer discovered incidentally in postoperative pathology specimen

The most common presentation of early GB cancer is incidental discovery after unsuspected cholecystectomy in the pathology specimen. In a study by Duffy et al., 47 % of the GB cancers were detected after laparoscopic cholecystectomy [24, 25]. In those patients, a careful review of the GB specimen for the level of invasion (T staging), assessment of resected margins and search for malignancy in the nodes if any retrieved is important. Also, these patients need to be worked up carefully to rule out any metastatic disease. Documentation of spillage of bile or gall stones during the initial surgery must be done, as GB cancer is notorious to spread and recur at port sites and peritoneal surfaces. Further management after cholecystectomy is based on staging and surgical margins.

3.1 Management Based on T Staging

For carcinoma in situ (Cis) and T1a lesions (i.e., lesion confined to the mucosa), the treatment recommendation is simple cholecystectomy. Most often, these lesions are identified after cholecystectomy as incidental cancers found in the specimens. A high degree of suspicion is required to identify GB cancer by preoperative imaging. In a study of 27 patients with T1a lesions, eight of whom underwent lymph nodal dissection; none had lymph nodal metastasis [26]. A careful review of the pathology for the level of invasion and negative margins is important. There is no need for additional surgical procedures or re-exploration in these patients if the staging workup is negative. The five-year survival rate for Cis and T1a lesions ranges from 85 to 100 % [27–29].

3.2 Tumors Confined to Muscularis Propria (T1b)

According to the AJCC staging system, 7th edition, T1b lesion is one which invades the muscularis propria but does not involve the perimuscular connective tissue. Many studies show T1b lesion treated by laparoscopic cholecystectomy alone had a 5-year survival rate of around 90 % and in some others as high as 100 % [19, 27–29]. However, whether an operation beyond a simple cholecystectomy is needed remains controversial.

Otero et al. [30] concluded that for T1b lesions, additional procedures are needed after cholecystectomy, which was a recommendation shared by Principe et al. [31] and in the review by Miller et al. [23]. Most data, however, argue against radical resection. The occurrence of lymph nodal metastasis was only 3.8 % in the study by You et al. [26]. Similarly, in a study in 1996 by Tsukada et al. [32], all 15 patients with T1 lesions had no lymph nodal metastasis. De Aretxabala et al. concluded after their study in 46 patients that lesions with invasion of muscle layer do not need additional procedures following cholecystectomy.

It must be stated that the 2009 NCCN guidelines mention additional hepatic resection and lymphadenectomy for T1b lesion [33]. We do not routinely perform such radical resection except in cases with clinically positive lymph node metastases. Our reasoning is since lymphatics are only present in the subserosal layer; those tumors that have not yet fully penetrated the muscularis layer have a minimal risk of lymph nodal involvement. Hence, nodal dissection is not required for T1b lesions. However, an open discussion with the patient is worthwhile. There is convincing enough data to demonstrate that early-stage cancers that have not penetrated through the entire muscularis layer can be adequately treated by cholecystectomy alone [34, 35].

In those patients where diagnosis of T1 GB cancer is made after initial cholecystectomy, a careful review of the specimen for level of invasion and margins must be done. Patients will need an additional procedure only if the margins or lymph nodes are positive or the depth of invasion is higher than T1. Postoperatively if CT and CEA levels are normal, they will need routine follow-up as shown in algorithm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Algorithm of management of gallbladder cancer

3.3 Tumors Penetrating Full Thickness of the Muscularis Propria into Subserosa: T2 (stage 2)

Tumors that penetrate through the entire thickness of the muscularis layer but do not involve the serosa are defined as T2 lesions and have been grouped as stage 2 per the AJCC staging (Table 1). The subserosa (avascular) is the space between the muscle layer and the outer serosal layer. Lymphatics are present immediately outside of the muscle layer in the subserosa. Hence, T2 lesions have a high incidence of lymph nodal metastasis ranging from 20 to 40 % (Table 2). While performing a simple cholecystectomy, this is the plane where the gallbladder is dissected off the GB fossa from the liver. The serosa on the GB fossa that is present on the liver surface and which is left behind after dissecting the GB along the avascular subserosal plane in a simple cholecystectomy is called the cystic plate. Therefore, a conventional cholecystectomy in a T2 lesion will result in high likelihood of positive margins as the tumor plane may be violated. Hence, these patients have to be subjected to additional exploration if R0 resection needs to be achieved.

Table 1

Seventh edition of AJCC staging

AJCC staging 7th edition |

|---|

Primary Tumor (T) |

TX—primary tumor cannot be assessed T0—no evidence of primary tumor Tis—carcinoma in situ T1—tumor invades lamina propria or muscular layer T1a—tumor invades lamina propria T1b—tumor invades muscular layer T2—tumor invades perimuscular connective tissue; no extension beyond serosa or into liver T3—tumor perforates the serosa (visceral peritoneum) and/or directly invades the liver and/or one other adjacent organ or structure such as the stomach, duodenum, colon, pancreas, omentum or extrahepatic bile ducts T4—tumor invades main portal vein or hepatic artery or invades two or more extrahepatic organs or structures Regional Lymph Nodes (N) N0—no regional lymph node metastases N1—metastases to nodes along the cystic duct, common bile duct, hepatic artery and/or portal vein |

N2—metastases to periaortic, pericaval, superior mesenteric artery and/or celiac artery lymph nodes Distant Metastasis (M) M0—no distant metastasis M1—distant metastasis |

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIB | T1-3 | N1 | MO |

Stage IVA | T4 | N0-1 | MO |

Stage IVB | Any T Any T | N2 Any N | M0 M1 |

Table 2

Results of cholecystectomy alone versus additional re-exploration and resection for T2 lesions

Author, year, country | N | Only cholecystectomy 5-year survival (%) | Re-exploration and additional radical resection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N | Nodal disease (%) | Positive margins (%) | 5-year survival (%) | |||

Shirai, 1992 [28], Japan | 35 | 40 | 10 | 30 | 20 | 90 |

Fong, 2000 [22], USA | 16 | 19 | 37 | 33 | NR | 61 |

Chijiwa, 2001 [55], Japan | NR | 17 | 28 | 39 | 21 | 59 |

Wakai, 2002 [56], Japan | 6 | 50 | 7 | 28 | 0 | 100 |

Toyonaga, 2003 [57], Japan | 25 | 65 | 18 | 20 | 63 | 38 |

Foster, 2007 [58], USA | 10 | 38 | 19 | 33 | NR | 78 |

Hence, for a T2 lesion, the recommendation is a cholecystectomy, along with resection of sufficient liver to achieve a negative margin, and a regional lymph node dissection. Such an operation is known as an extended or radical cholecystectomy. The incidence of nodal disease in T2 lesion has been reported from 23 % in a series by Konstantinidis [36] to as high as 61 % by Duffy et al. [24]. This group of patients benefit from re-exploration and additional radical or extended resection to achieve negative margins. Similarly, Ogura et al. [35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree