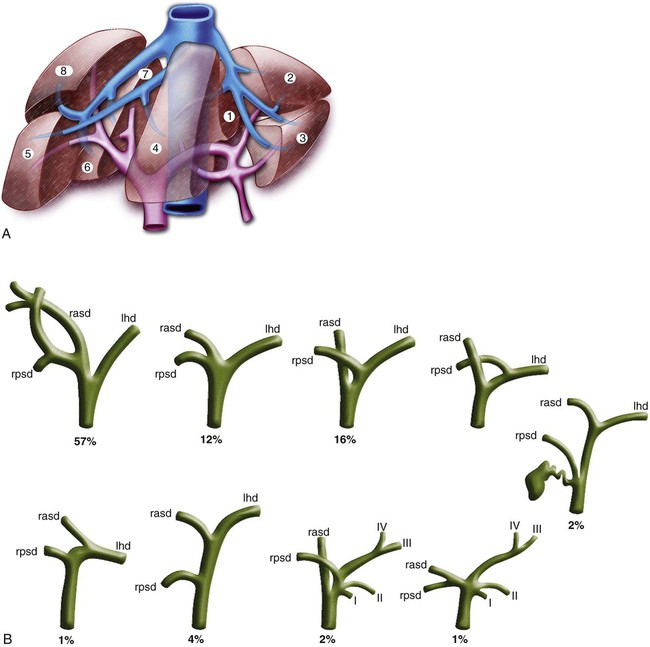

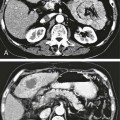

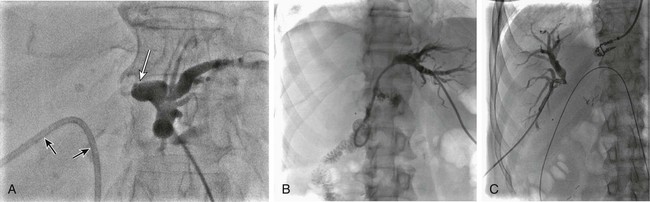

In the presence of MBDO when ERBD cannot be performed, PTBD is indicated: • For treatment of cholangitis. Hydration and antibiotic therapy are successful initial interventions for 80% to 85% of patients with cholangitis.1 Those with ongoing sepsis despite these therapies require urgent biliary decompression, and those who do respond to initial medical therapies frequently require subsequent biliary drainage. • To relieve pruritus. Medical therapies including the bile acid–binding resins cholestyramine and colestipol, antihistamines, naloxone, and rifampin are variably effective treatments for pruritus related to cholestasis. Biliary drainage is an effective treatment2,3 when results of these medications are suboptimal, even when only one or two segments of the liver can be effectively drained. Following biliary drainage for this indication, symptomatic improvement is often observed within 24 hours. • To relieve symptoms of jaundice. Symptoms such as nausea and anorexia may improve with delivery of bile salts to the intestine. • To reduce serum bilirubin to facilitate administration of chemotherapy. Some chemotherapeutic agents require intact mechanisms of bile excretion for safe use, and others require dose modification when the serum bilirubin is elevated. To receive optimal chemotherapy at full dose, some patients may require biliary drainage to lower serum bilirubin.4 • Prior to surgery. Preoperative biliary drainage is highly controversial; many studies have shown it increases complication rates.5–8 One meta-analysis suggested neither positive nor negative outcomes in association with preoperative biliary drainage.9 Others have suggested improved postoperative results following internal drainage.10–12 • In association with other percutaneous biliary procedures such as bile duct biopsy and placement of biliary stents or brachytherapy catheters Relative contraindications include: • Coagulopathy. Every effort should be made to correct or improve coagulopathy prior to biliary drainage procedures. • Allergy to iodinated contrast agents. Patients with history of allergy to iodinated contrast material should be appropriately premedicated because contrast material may be introduced into the vascular system or absorbed during biliary drainage. Typical premedication regimens include administration of both an antihistamine and a corticosteroid. • Ascites. Large ascites may complicate transhepatic biliary access and intervention, and leakage of ascites around biliary catheters may occur. Consider paracentesis in such instances. Left-side biliary access may provide an access window away from ascites. • All contraindications to PTBD • Sepsis. PTBD with minimal manipulation is indicated for patients with sepsis and bile duct obstruction. If appropriate, stent placement can be considered after sepsis has resolved. • Potential surgical candidate. Because determination of resectability presupposes knowledge of the diagnosis, metallic stents are not placed when the diagnosis is not known. Historically, biliary drainage catheters rather than biliary stents have been placed for preoperative patients. There is a trend in recent literature to suggest that stents can be safely used in preoperative patients with low bile duct obstruction.13–16 Because this represents a substantial change in approach, local surgical preferences should be sought and considered. • Benign disease. Metallic stents are generally not used for treatment of benign causes of biliary obstruction. Example equipment needs include: • Water-soluble, nonionic radiographic contrast material • #11 blade or other suitable blade for dermatotomy creation • 21-gauge needle with stylet, capable of accepting a 0.018-inch guidewire • A coaxial introducer system including an innermost component tapered to accept a 0.018-inch guidewire and an outer 4F or 5F sheath. Examples include the Neff Percutaneous Access Set (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Ind.) and the GrebSet (Vascular Solutions, Minneapolis, Minn. ). • 4F or 5F catheters (e.g., Berenstein, C2) • Guidewires, including a torquable 0.035-inch hydrophilic wire and a 0.035-inch Amplatz Super Stiff guidewire (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass.) • 6- to 10-mm inflatable balloon catheters Understanding the segmental anatomy of the liver is essential for interventional radiologists who perform biliary interventions. The Couinaud classification of liver anatomy (Fig. 134-1, A) is most useful in this regard. The liver is divided right from left by the plane that includes the middle hepatic vein and gallbladder fossa. Important common variants of biliary anatomy must be understood (Fig. 134-1, B). Several of these involve variant insertions of the right-sided sectoral ducts. One common example occurs when the right posterior sectoral duct drains to the left hepatic duct instead of joining the right anterior duct. In certain hilar occlusions where this anatomic variant is present, drainage of the right posterior sector may confer drainage of 6 liver segments (segments 1-4, 6, and 7), whereas drainage of the anterior sector would accomplish drainage of only 2 segments (segments 5 and 8) in such instances. Therefore, careful study of preprocedure imaging and real-time scrutiny of the procedural cholangiogram for the presence of variant biliary anatomy is essential. Biliary obstruction may cause one part of the biliary tree to be separated from another part, and this separation is termed isolation. The extent or degree of isolation may be characterized as complete or incomplete. In complete isolation, there is no obvious remaining connection between the segments of biliary tree that have been separated by the obstruction (Fig. 134-2). Contrast material injected into the bile duct during cholangiography stops at the point of obstruction, and catheter-guidewire manipulations are required to find the obliterated connection between completely isolated segments of bile duct. Incomplete isolation, on the other hand, occurs when disease has pathologically narrowed segments of bile duct that still remain in communication. This is depicted by passage of injected contrast material through areas of bile duct narrowing into other portions of the biliary tree (Fig. 134-3). Some refer to incomplete isolation as impending isolation to convey the likelihood that with time, disease progression will transform incomplete isolation into complete isolation (Fig. 134-4). Clinically, incomplete isolation is important because it is functionally equivalent to partial obstruction; when it is present, there are poorly drained segments of the biliary tree that are substrates for infection. Instrumentation or injection can contaminate such ducts with bacteria, leading to cholangitis.

Management of Malignant Biliary Tract Obstruction

Indications

Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage

Contraindications

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography

Biliary Stent Placement

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Right Hepatic Lobe

Pathologic Anatomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Management of Malignant Biliary Tract Obstruction