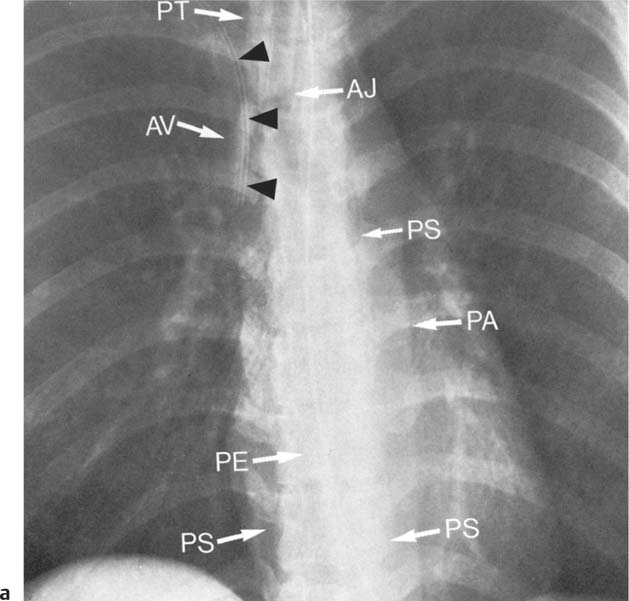

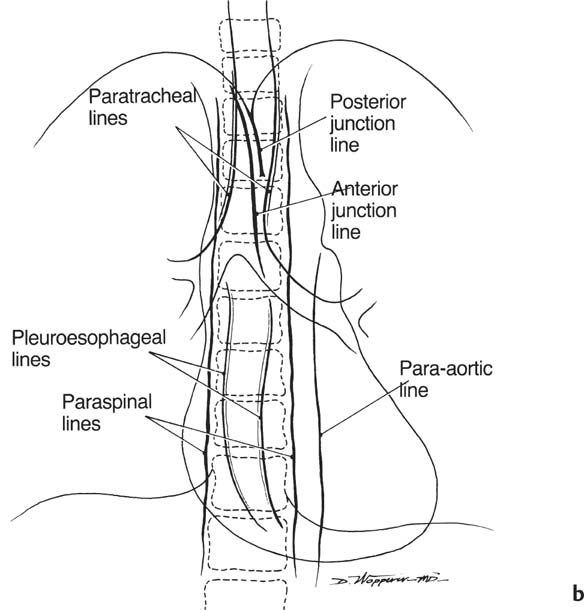

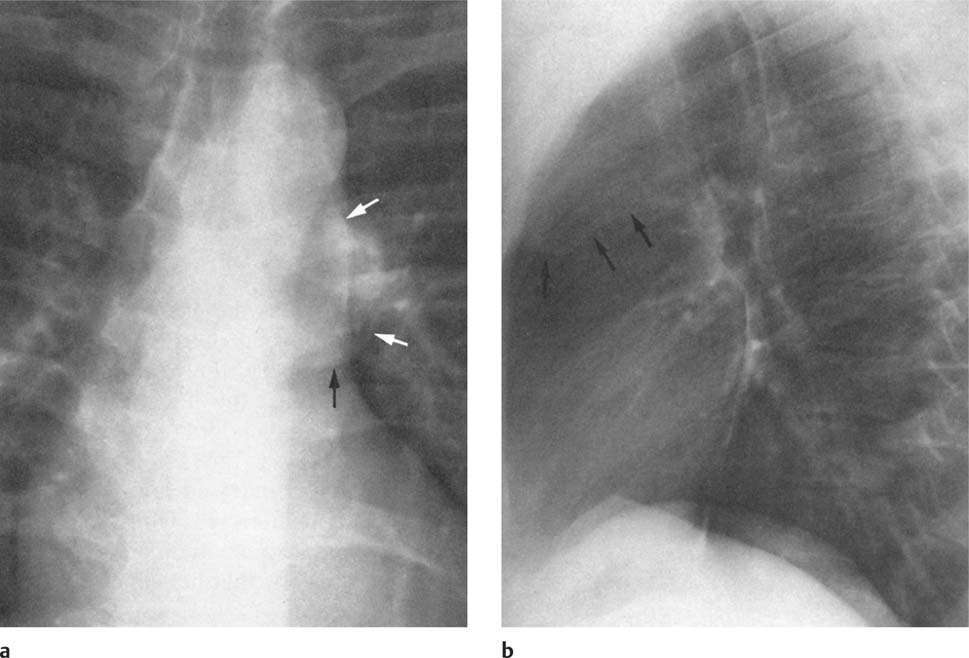

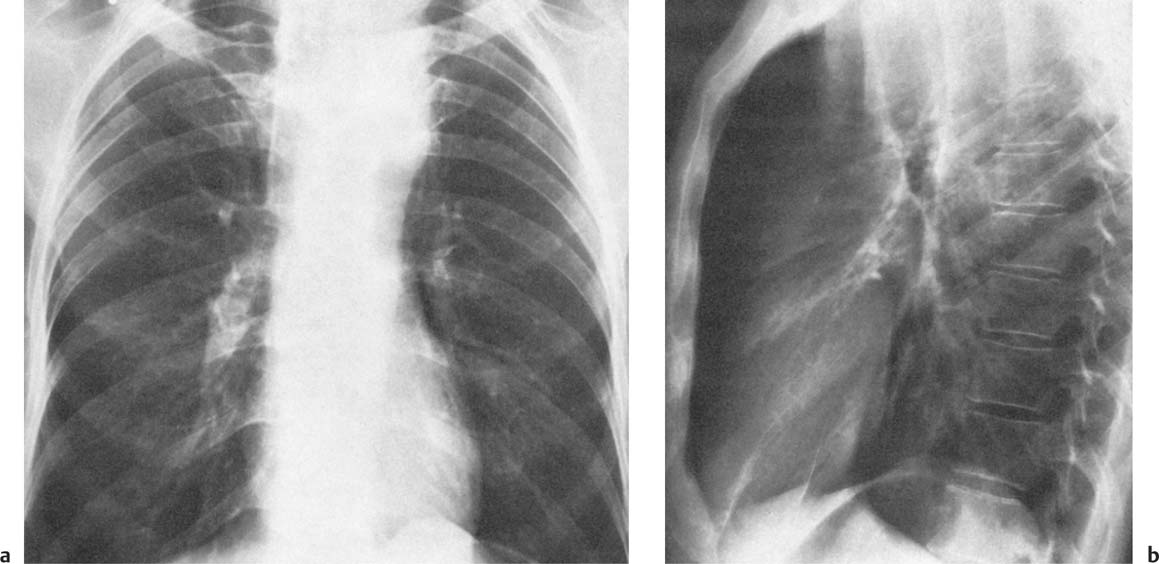

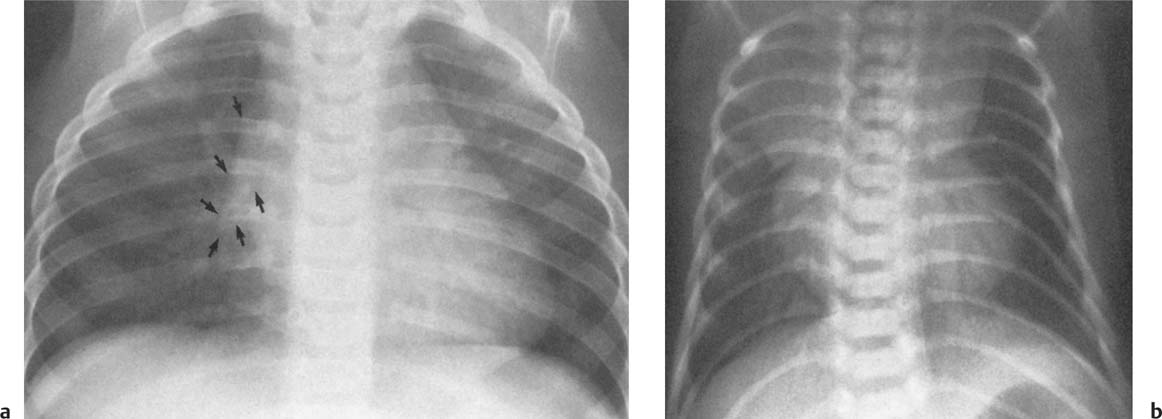

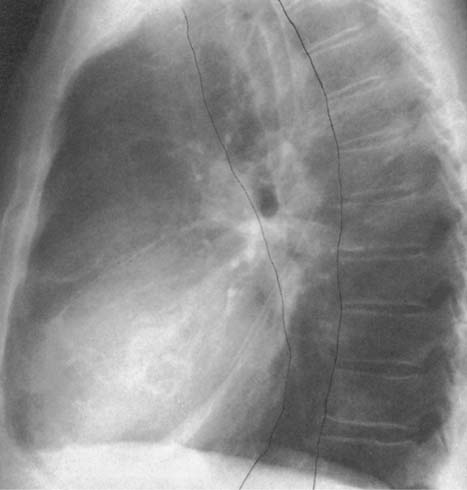

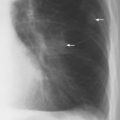

2 Mediastinal or Hilar Enlargement The mediastinum is defined as the extrapleural space within the thorax lying between the lungs. The soft-tissue structures that compose the margins of the mediastinum and abut against the lungs usually cast discernible shadows on roentgenograms. These lung-mediastinal interfaces are keys to the radiologic analysis of the mediastinum. Well-penetrated high kVp films are essential to visualize the interfaces lying behind the lateral margins of the mediastinum and heart. Opacification of the esophagus may further help in delineating the suspected lesion. Although careful analysis of the mediastinum on plain films is not a replacement for computed tomography of known or suspected mass lesions, it is important in detecting early or unsuspected lesions from routine chest roentgenograms. Differentiation of mediastinal disease from cardiac, pericardial, pleural, and pulmonary lesions is better done with CT. Useful lines and signs in anteroposterior projection; Fig. 2.1: The paraspinal line may be displaced by pleural fluid, a paravertebral abscess, hemorrhage from a dorsal spine fracture, or extravertebral extension of a neoplasm. The more prominent the aorta, the wider the space between the left paraspinal line and the spine. Visualization of normal paraesophageal and posterior junction lines are due to the lack of interposed soft-tissue or esophageal distention. The paratracheal and parabronchial lines become wider (over 2 to 3 mm) with pleural thickening or fluid, mediastinitis, and hemorrhages. An uneven outline is likely due to paratracheal lymphadenopathy or tumor. The normal azygos vein is seen as a spindle shaped dense widening of the right paratracheobronchial line at the level of the tracheal bifurcation, and its transverse diameter may vary with posture and Valsalva maneuver, which can be used to differentiate the azygos vein from an enlarged lymph node. In upright position it is normally less than one centimeter wide. Increased systemic venous pressure (congestive heart failure, acute pulmonary hypertension due to embolism, constrictive pericarditis), portal thrombosis, ascending thrombosis of the vena cava, or absence of the subhepatic portion of the vena cava, may cause dilatation of the azygos vein. The anterior borders of the upper lobes join immediately behind the manubrium to form the anterior junction line slightly to the left of midline. It is not seen in infants and young children because of the presence of the thymus. Enlargement of the aorta, hemorrhage, adenopathy, or tumor may interpose between the lungs at this point. On the left side the paraesophageal line is not consistently visualized, but the para-aortic line is continuous with the profile of the aortic arch. This line is often curved due to elongation of the aorta. A discontinuity may represent coarctation of the aorta (Fig. 1.40). Coarctation may also cause convexity of the profile of the left subclavian artery above the aortic knob. The angles between the aorta and the subclavian artery as well as the indentation between the aorta and the superior surface of the pulmonary artery may be obliterated by lymphadenopathy or tumor. A double profile of the main pulmonary artery segment, if not explained by the left main artery, is likely due to a neoplasm, usually anterior to the pulmonary artery (hilum overlay sign, Fig. 2.2). Fig. 2.1a Mediastinal lines as seen in anteroposterior projection. The location of superior vena cava, trachea, and esophagus are demonstrated by a CVP line and tracheal and esophageal tubes. PT = paratracheal line, AV azygos vein, AJ anterior junction line, PS = paraspinal line, PA para-aortic line, PE paraesophageal line. Central venous catheter (arrow heads). Fig. 2.1b Graphic presentation of the mediastinal lines. Fig. 2.2a, b Hilum overlay sign, a A double profile of the main pulmonary artery segment, which appears enlarged (arrows), b Lateral film shows that there is a mass (lymphoma) in the anterior mediastinum (arrow), which projects over the left hilum in posteroanterior projection. Widening of the whole mediastinum in anteroposterior projection and disappearance of the normal mediastinopulmonary interfaces occurs especially in hemorrhage and in postoperative bleeding, but it may occur with extensive infiltrating neoplasm, mediastinal amyloidosis, mediastinal fibrosis, and inflammation. Since the cephalic border of the anterior portion of the mediastinum ends at the level of the clavicles while that of the posterior portion extends much higher, a lesion clearly visible above the clavicles on the frontal view must lie entirely within the thorax. The more cephalad an upper mediastinal mass extends while still remaining visible, the more posteriorly it lies. A thoracic lesion in anatomic contact with the neck or extending into it will be obliterated along its upper lateral borders by the cervical soft tissues (cervicothoracic sign, Fig. 2.3). Thoracoabdominal mass lesions may be visible through the diaphragm, since they are in contact with the posterior lower lobes. Lack of downward convergence of the lower border of such a lesion (iceberg sign, Fig. 2.4) indicates that a considerable portion of the mass is in the abdomen. An iceberg sign is common in thoracoabdominal aneurysms, esophagogastric lesions, and azygos continuations of the inferior vena cava. Also, a retroperitoneal tumor may extend into the thorax and widen the inferior paravertebral shadow. In about 9% of infants and young children the normal thymus may produce a sail shadow projecting from the upper mediastinum on the frontal film (Fig. 2.5). The sail shadow is differentiated from right upper lobe consolidation by its well defined vertical lateral border, and from encapsulated pleural effusion by its sharp inferior angle. The lateral borders of the normal thymus may be indented by adjacent ribs, causing a subtle wavy margin on the frontal projection that is not seen in thymic tumors or in other anterior mediastinal masses. In an infant, pneumomediastinum may dissect the thymus from the rest of the mediastinum and elevate it like a ‘spinnaker sail.’ If a thymus in the neonate less than 4 days of age is not visible in anteroposterior or lateral radiographs of the chest (the retrosternal area is lucent, the anterior borders of the heart and great vessels are clearly defined, and in the frontal projection the mediastinum is narrow), thymic aplasia should be suspected. Absence of the thymus and parathyroids (immunologic deficiency and tetany) is called DiGeorge syndrome (Fig. 2.6). Hypoplastic mandible, deformities of the ear and anomalies of the aortic arch may be associated. Thymic aplasia or hypoplasia may be seen also in severe, combined immunodeficiency syndromes. In lateral view, the mediastinum also has significant profiles (Fig. 2.7). Effacement of the aortic arch and tracheal wall profiles indicates interposed soft tissue. The posterior tracheal band is a 3-mm-wide band extending from the upper mediastinum to the lower lobe bronchi. It is well visualized in patients who have a sizable azygoesophageal recess filled by the right lung. Carcinoma of the esophagus, other mediastinal neoplasms, bleeding, or infection may obliterate a previously well-visualized posterior tracheal band or cause its general or localized widening (Fig. 2.8). The posterior margin of the inferior vena cava is always seen in good-quality lateral films. Its absence is rare (Fig. 2.9). Differentiation of enlarged hilar blood vessels from hilar lymph adenopathy may be easier if one remembers that blood vessels tend to be parallel with bronchi, whereas lymph nodes actually surround them and may produce accentuated cross-sectional shadows of main bronchi in the lateral view. Mediastinal contrast enhanced CT greatly helps differentiation of blood vessels from other structures. The lines and signs presented above are helpful in localizing a lesion. Division of the mediastinum into anterior, middle, and posterior mediastina is more useful than strictly anatomical subdivision. This artificial division of the mediastinum into anterior, middle, and posterior portions varies among different authors. The division used in this presentation is shown in Fig. 2.10. The shape, size, and radiographic structure of mediastinal mass lesions in conventional films often provide insufficient information for definitive diagnosis and computed tomography is required for better anatomical definition. Different types of lesions tend to occur at different anteroposterior subdivisions of the mediastinum. Associated pulmonary or pleural changes provide further information for differential diagnosis. Fig. 2.3a, b Cervicothoracic sign, a In frontal projection, the upper mediastinal mass extends over the clavicles and joins into the soft tissues of the neck, indicating posterior position of the mass, as shown also in b by the lateral film. Carcinoma of the esophagus. Fig. 2.4 Iceberg sign. Nodular widening of the paraver tebral soft tissues (arrows), more so on the left. Para-aortic metastases of a testicular carcinoma extending beyond the diaphragm. Fig. 2.5a, b Thymic sail shadow, a A small “sail” that has a well-defined border and sharp inferior angle (arrows), b Thymus presenting as an upper mediastinal mass with a sharp inferior angle on the right side. The most common lesions which cause mediastinal widening are summarized in Table 2.1 according to their usual location. Enlarged lymph nodes in this context refer to masses which are recognizable on plain radiographs, on which normal-sized lymph nodes are not seen unless they are calcified. The question of how to define the boundary between normal and enlarged individual lymph nodes, commonly encountered in CT or more resently in PET-CT, will therefore not be discussed. In Table 2.2, diseases which cause hilar and/or mediastinal lymph node enlargement are discussed, while diseases causing diffuse mediastinal widening are presented in Table 2.3.

Anterior Mediastinum | Middle Mediastinum | Posterior Mediastinum |

Aneurysm of ascending aorta Lymphoma (most common) Pericardial cyst Retrosternal thyroid Teratoid lesion Thymic lesion | Aneurysm of aortic arch Azygos vein enlargement Bronchogenic cyst Esophageal lesions Hiatal hernia Lymph node enlargement (most common) Thyroid tumor (Hilar vascular dilatation) | Aneurysm or tortuosity of descending aorta (most common) Lymph node enlargement Neurogenic tumor Paraspinal manifestations of spinal lesions |

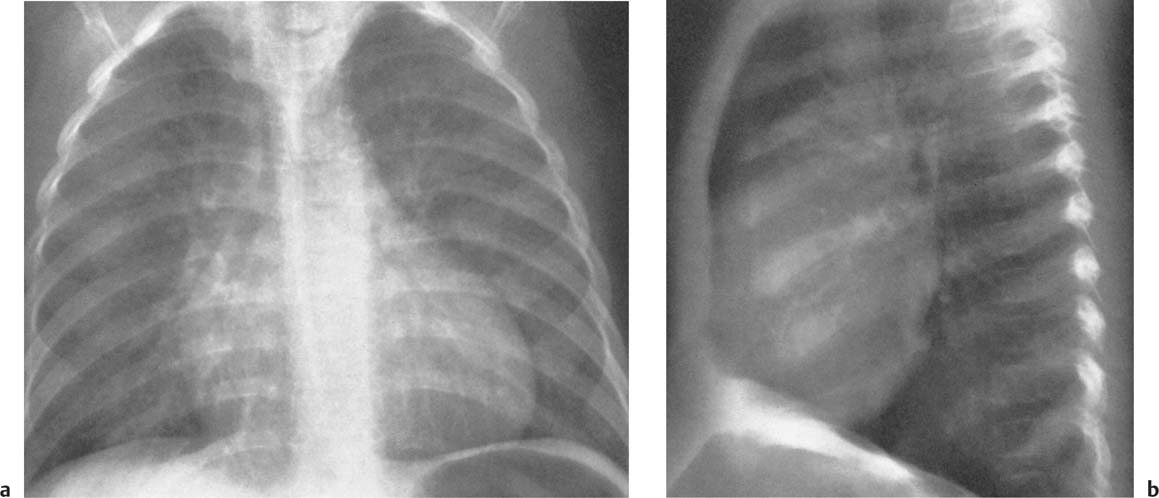

Fig. 2.6a, b DiGeorge syndrome. Absence of thymus is suggested a by the narrow upper mediastinum, presence of the anterior junction line in a small child, and b radiolucency of the retrosternal space in the lateral view.

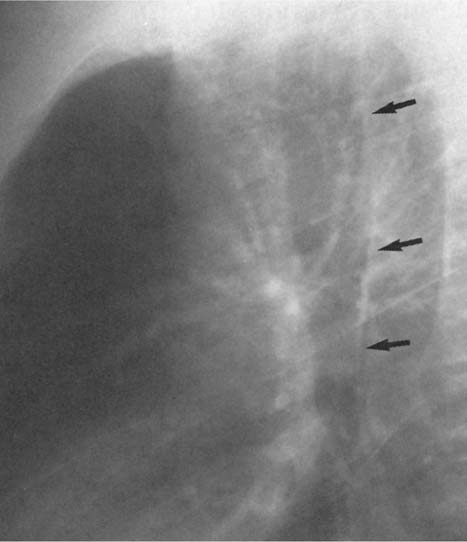

Fig. 2.7 Normal posterior tracheal band (arrows)

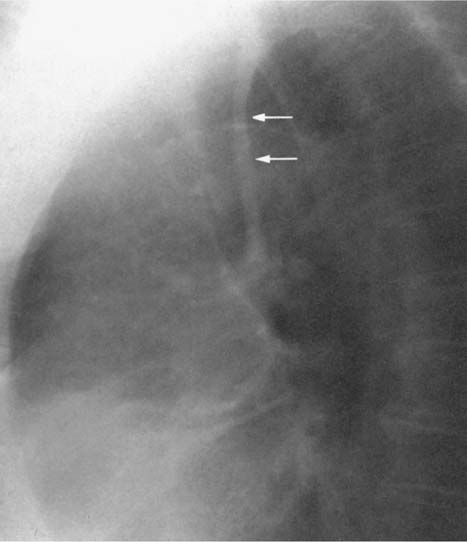

Fig. 2.8 Thickening of the posterior tracheal band (arrows).

Fig. 2.9 Congenital absence of the proximal IVC. The silhouette of the inferior vena cava, normally present in the lateral film, is lacking. Blood is conducted via the azygos vein.

Fig. 2.10 Division of the mediastinum into three (artificial) compartments. “Anterior mediastinum” refers to front of the trachea or of the posterior cardiac silhouette. “Posterior mediastinum” refers to area posterior to the anterior paraspinal line. “Middle mediastinum” refers to the compartment between these two artificial lines.

Disease | Radiographic Findings | Comments |

Neoplastic diseases (malignant or benign) |

|

|

Bronchogenic carcinoma (Fig. 2.11) | Unilateral hilar node enlargement involving bronchopulmonary and tracheobronchial nodes, in some cases paratracheal and posterior mediastinal nodes. | Influence of cell type: 1 A hilar mass as the sole roentgenographic abnormality is characteristic of an undifferentiated small-cell carcinoma; 2 Generalized mediastinal widening almost certainly indicates spread from an undifferentiated carcinoma; 3 Hilar or mediastinal lymph node enlargement is rare in alveolar cell (bronchiolar) carcinoma. |

Hodgkin’s disease (Fig. 2.12) | Bilateral but asymmetric enlargement, especially of paratracheal and tracheobronchial nodes, frequently also anterior mediastinal and retrosternal nodes. Bronchopulmonary nodes are less frequently enlarged than the more central ones. Unilateral involvement is very rare. | Mediastinal lymph node enlargement is seen on the initial chest roentgenogram in approximately 50% of patients. May be associated with pulmonary involvement or pleural effusion in advanced cases. |

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Bilateral, asymmetric node enlargement similar to Hodgkin’s disease. | May occasionally present as parenchymal consolidation without associated lymph node enlargement. |

Leukemia | Usually symmetric enlargement of mediastinal and bronchopulmonary nodes. | Occurs in 25% of patients, more commonly in lymphocytic than in myelocytic leukemia. Pleural effusion and parenchymal involvement may be associated. |

Immunoblastic lymphadenopathy (a hyperimmune disorder of B lymphocytes) | Bilateral, asymmetric node enlargement similar to Hodgkin’s disease. | Lungs are occasionally affected in a pattern similar to Hodgkin’s disease. |

Heavy-chain disease (a plasma cell dyscrasia) | Symmetric enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes. | Hepatosplenomegaly is common, lung involvement rare. |

Bronchopulmonary amyloidosis (a plasma cell dyscrasia) (Fig. 2.13) | Symmetric hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement. Enlarged nodes may be densely calcified. | Sometimes associated with diffuse pulmonary involvement. |

Lymph node metastases (Fig. 2.14) | Unilateral or bilateral enlargement of either hilar or mediastinal nodes or both. | May be associated with lymphangitic changes in the lungs (see Table 2.3). |

Castleman’s disease (giant lymph node hyperplasia) | hilar or mediastinal nodes or both. Large circumscribed mediastinal mass is the most common presentation. | lymphangitic changes in the lungs (see Table 2.3). This rare benign condition may be associated with fever, anemia and gammaglobulinemia. Two types can be differentiated. Type 1: the hyaline vascular type (90%), almost always local, with no systemic symptoms; Type 2 the plasma-cell type, which may be multicentric and associated with systemic symptoms. |

Bacterial and mycoplasma infections |

|

|

Primary tuberculosis (Fig. 2.15) | Mostly unilateral hilar (60%) or hilar and paratracheal (40%) lymph node enlargement. Bilateral node enlargement is a rare presentation. | Hilar node enlargement differentiates primary tuberculosis from secondary (reunification) tuberculosis. In the latter, there is no observable lymphadenopathy. |

Tularemia (Francisella tularensis) | Unilateral hilar node enlargement with characteristically oval pneumonic consolidations and pleural effusion. | Ipsilateral hilar node enlargement occurs in 25–50% oftularemic pneumonias. Is a potential bioterrorism agent. |

Pertussis (whooping cough) | Unilateral hilar node enlargement. | Often associated with ipsilateral segmental pneumonia and atelectasis. |

Anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) | Symmetric enlargement of all lymph nodes or generalized mediastinal widening. |