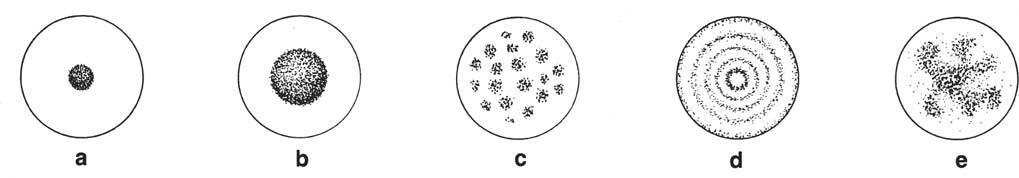

4 Intrathoracic Calcifications Calcifications in chest roentgenograms appear commonly. They are most frequently found in asymptomatic individuals as signs of “burned-out” disease or as the result of physiological calcification, such as calcification of the cartilagenous portions of the ribs or calcifications of the tracheobronchial tree. The causes of calcification of the soft tissues surrounding the thoracic cage are the same as those causing generalized calcification of periarticular soft tissues, and the reader should consult Chapter 7, Table 7.3. Calcification of the aorta and other arteries is a common feature of old age in western countries and may have little diagnostic significance unless associated with other changes such as aneurysmatic dilatation of the artery. Atherosclerotic calcifications also commonly occur in the mitral and aortic annuli of the heart. Arteriosclerotic calcification of the coronary arteries is likewise common, but due to its high kVp, the routine chest radiograph rarely reveals such small calcifications in the heart or elsewhere. Multidetector CT is used for better visualization of cardiac calcifications. The lung is the most frequent visceral site of metastatic calcifications, which are most commonly associated with renal failure. Metastatic calcifications of the lungs are, however, rarely demonstrated radiographically. Granulomatous calcifications (Fig. 4.1) of the pulmonary parenchyma are common and diagnostically important, since demonstration of a calcified central nidus or laminated calcification in a pulmonary nodule is the most reliable sign of benignancy. Diffuse or miliary calcification of the pulmonary parenchyma may be caused by several conditions but is less common than nodular calcification. Miliary calcifications of healed disseminated infections, mitral stenosis, or alveolar microlithiasis usually have distinctive features. Calcification of pulmonary metastases is uncommon. The most common primary neoplasm with calcified pulmonary metastases is osteosarcoma, but calcification may rarely occur in metastases of any mucinous adenocarcinoma. An eccentric calcification in a pulmonary mass can occasionally be found in a bronchogenic carcinoma engulfing a pre-existing granulomatous calcification. Calcifications occur frequently in the thyroid, and may present as an upper mediastinal mass. Unfortunately, calcification of the thyroid mass is not a reliable sign of benignancy of the lesion. Other mediastinal tumors often have distinctive calcifications, e.g., demonstration of a bone or a tooth within a mass lesion is diagnostic for a dermoid cyst. Calcification of the pleura may have the form of continuous sheets or multiple calcified plaques. The former type is usually unilateral and secondary to an old pleural infection (especially empyema or tuberculosis), or hemothorax. In such a case, calcium is usually deposited on the thickened visceral pleura and there is a thick layer of soft-tissue density between the calcification and the thoracic wall. Calcified or noncalcified plaques of the parietal pleura are typical of asbestosis, and the changes are usually bilateral. Associated pulmonary fibrosis is often lacking. If distinct calcification of apparently thickened pleura is lacking, nonpleural masses abutting the pleura should be considered. Such a finding may also be caused by intercostal fat or unusually prominent chest musculature. The latter is most common in the region from the 5th to 9th ribs in adults with inwardly concave lateral chest walls. Hilar calcifications most commonly represent healed granulomatous infection of lymph nodes. They are usually stippled or amorphous and are irregularly distributed throughout the node. Ring calcification of the periphery of the lymph nodes (“eggshell” calcification) is unusual and characteristic of silicosis, but may very rarely also be found in sarcoidosis and in irradiated Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Fig. 4.1 Diagram of benign calcifications occurring in peripheral pul monary nodules: a central nidus, b target lesion, c multiple punctate foci, d laminated, e conglomerate or “popcorn.” Types a and c occur in granulomas or hamartomas. Type b is characteristic of histoplasmosis. Type d occurs only in granulomas and type e is characteristic of hamartomas.

Location of the calcification | Causes or associated condition | Comments |

Atherosclerosis Aneurysm Aortitis | Increased diameter of the aorta indicates an aneurysm. Increased distance between intimal calcification and the outer wall of the aorta suggests dissecting aneurysm. Heavy calcification of the dilated ascending aorta is characteristic of syphilitic aortitis. | |

Sinus of Valsalva (usually best seen in the lateral view) (Fig. 4.2) | Aneurysm of the sinus of Valsalva or, rarely, arteriosclerosis | Calcification may occur in the wall of the sinus and in the adjacent aorta. Heavy in syphilitic aneurysms. A thrombus in the aneurysm may calcify. |

Coronary arteries (Fig. 4.4) | Arteriosclerosis of the coronary arteries (common) Coronary artery aneurysm (very rare) | The most common site of visible calcification is the proximal left circumflex artery. Easier to recognize in the lateral view as parallel linear or tubular calcifications. |

Aortic annulus or aortic valves (Fig. 4.5) | Calcified annulus only: arteriosclerosis Valves with or without calcified annulus: Rheumatic aortic valve disease Arteriosclerosis Endocarditis Congenital defect of valve Hypercalcemia | Calcification of the annulus is usually heavy and distinct, whereas valvular calcifications are stippled and often superimposed by annulus, and not seen on plain films. If aortic valve disease appears before the age of 50 it is likely to be of rheumatic origin. |

Mitral annulus (Fig. 4.6) | Arteriosclerosis | A dense curved or annular calcified band around the mitral valve. Usually insignificant, but rigid annulus may cause functional insufficiency of the mitral valve. |

Mitral valve | Rheumatic mitral valve disease | Calcification may be indistinct and easily missed. The amount of calcification does not reflect the degree of functional disturbance. |

Myocardium (Fig. 4.7) | Myocardial infarct Myocardial aneurysms due to infarct or rarely other causes such as syphilis Myocardial damage such as trauma, myocarditis, rheumatic fever (rare) Congenital (rare) Hyperparathyroidism (rare) Vitamin D overdosage (rare) | Calcification is usually smaller than the infarct. Most common at the apex with or without aneurysm. |

Left atrium (rare) (wall or intra-atrial) | Rheumatoid mitral valve disease. Left atrial myxoma or thrombus | Calcification of the wall of the left atrium is seen as a thin, ring-like density in the frontal view. If the left atrial appendage is calcified, it is always due to a calcified thrombus. A calcified wall and a calcified thrombus may be difficult to differentiate from each other on the lateral view. |