Bronchiolitis, reactive airway disease (RAD), viral infections of the lower airways

Fig. 1.146a, b |

Minimal interstitial prominence, peribronchial thickening, hyperinflation (especially in viral infections). The hilar lymph nodes are increased in size rather than density; the outline is hazy. |

Episodes of coughing, possibly febrile, signs of infection.

Seasonal occurrence of RSV infections, mainly in autumn and winter. |

Measles |

Hila are dense, with prominent bronchovascular markings. In the exanthematous phase of measles pneumonia, the hila are widened and more dense, and lung markings are increased; miliary nodules are also present adjacent to the hila. |

Nowadays rare as a result of vaccination programs. |

Pertussis |

The increased dense hilar markings and perihilar signs (“shaggy heart”) reflect bronchitis in the cartarrhal stage. Increased pulmonary density occurs mainly in the basal segments. |

Diagnosed by the typical episodes of coughing in the convulsive stage, previously known as “catarrhal bronchitis.” |

CF

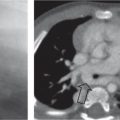

Fig. 1.147 |

Densely enlarged hila, initially moderate and increasing over ensuing years. Increasing pulmonary involvement with chronic infilitrative changes. Secondary hyperinflation and barrel chest deformity. Late findings resemble bronchiectasis. |

Onset in infancy, increasing and progressing in childhood. All signs of chronic infection with dyspnea and cough. |

Malignant lymphoma/leukemia

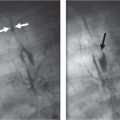

Fig. 1.148a–c

Fig. 1.149a–c, p. 86

Fig. 1.150, p. 86 |

Neoplastic mediastinal enlargement is mostly due to bilateral lymph node enlargement, particularly the paratracheal nodes. |

Diagnosed on bone marrow biopsy. Hematologic changes. Peripheral lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly. Bruises. Hilar involvement in Hodgkin disease in 50%, more common than in NHL. |

Mycoplasma infection |

Hilar enlargement accompanied by segmental pneumonia, particularly in the lower lobes (may even be unilateral). Radiographic appearance commonly resembles TB. |

Mild leucocytosis or normal white cell count. Organism must be positively proven. Bronchoalveolar lavage. |

LCH, malignant histiocytosis |

Mild, rarely marked hilar enlargement with sharp outlines. Evolves into interstitial pulmonary changes with small patches and confluent densities mainly in the bases. Emphysematous blebs, honeycomb lungs. |

|

Chronic aspiration |

Combination of bilateral hilar enlargement with multiple disseminated small patchy pulmonary densities. |

|

Fungal infection |

May be unilateral. Perihilar and occasional mediastinal lymph node involvement. Caution: air-space disease. |

|

TB

Fig. 1.151, p. 86 |

Nodular density to increasing hilar width. Primary complex in the lungs. Loss of the mediastinal contour. |

Small children to young school age. Gradual onset, with or without cough. Rarely febrile. Purified protein derivative (PPD) positive. May also be asymptomatic.

Increasingly seen in the western world after a period of relevant low incidence. |

Bacterial pneumonia |

In association with bilateral air space disease. Unlikely under 18–24 mo as mother’s antibodies still present. |

Clinical signs of pneumonia. |

Castlemann disease |

May involve single or multiple mediastinal compartments, including the hila. |

A group of rare lymphoproliferative disorders that are more common in adults. |

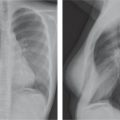

Sarcoidosis

Fig. 1.152a, b, p. 87 |

Characteristically symmetric lobulated lymph nodes; no pulmonary changes in stage 1, later (stage 2) there are small patchy densities in the lungs. Other lymph nodes can also become involved (tracheobronchial, paratracheal). |

This classic adult presentation is extremely rare in preteenaged children. |

Vascular causes: increased hilar and pulmonary vascular markings—active: left-to-right shunt |

Enlarged hila with enlarged vessel caliber. |

(see Table 1.75 ) |

Specific type: pulmonary hypertension |

Pulmonary arteries are significantly enlarged close to the hilum, and constricted peripherally (“arterial pruning”). |

|

Vascular causes: increased hilar and pulmonary vascular mark-ings—passive: cardiac failure |

Enlarged hila and increased caliber of the vessels that are hazy in outline. |

|

Vascular causes: increased hilar and pulmonary vascular mark-ings—pulmonary valve failure |

Massively enlarged hila, with decreased peripheral pulmonary vascular markings. |

Rare, most commonly in tetralogy of Fallot (see Table 1.78 ). |

Metastases |

Neoplastic in nature, lobulated or egg-shaped lymph nodes. |

|

Granulomatous infections |

More usually unilateral. |

TB, histoplasmosis. |

Other infections |

Milder hilar enlargement can occur in many acute and chronic pulmonary infections. |

Examples include RSV (often more right-sided), pertussis (now rare), chicken pox, measles, myco-plasma, bacterial pneumonia. |