Clinical Presentation

The patient is an 85-year-old man who presented with numbness of the hands. He describes losing his balance 4 months ago and injuring his knee. He was told he had torn some ligaments in his knee; however, his balance problems have continued to progress. Over the last several weeks, he has developed a numb sensation in both hands, as if he were wearing cotton gloves. This particularly involves the fingers and includes the dorsal and palmer aspects of the hands and forearms. The numbness has leveled off and is no longer getting any worse. However, it has reached a point where he is no longer able to write or fasten his buttons. He does not have numbness in his feet. He must use a walker to maintain his balance or he will fall, particularly if he turns toward the left. There has been no incontinence. During neurologic examination, it was noted he has a severely ataxic, weaving, and lurching gait. He can barely stand independently. He needs assistance to reach the examination table and to walk. When he attempts to touch his nose with his left hand, he can barely get his finger to his face. There is prominent ataxia in the left hand and foot. There is weakness throughout the left upper extremity and also some weakness of the right hand and left foot. There is severe loss of proprioception in the left hand and left foot. There is a radicular band of absent pinprick sensation on the right following a C6 pattern.

Imaging Presentation

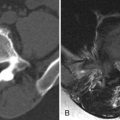

Sagittal T1 pre-contrast and post-contrast images of the cervical spine were obtained and reveal an ovoid intraspinal mass in the upper cervical region displaying intermediate T1 signal intensity and homogeneous enhancement. Axial imaging (not pictured) demonstrated the mass to be intradural and extramedullary and most compatible with a meningioma ( Fig. 47-1 ) .

Discussion

Spinal tumors are uncommon lesions. Spinal tumors can be classified as extradural, intradural/extramedullary, or intramedullary. Extradural lesions are most common, representing 60% of all spinal tumors, followed by intradural/extramedullary tumors (30%), and intramedullary tumors (10%). The majority of extradural lesions arise from the vertebrae and are most frequently metastases. Nerve sheath tumors, meningiomas, and drop metastases are the most common intradural/extramedullary masses, with nerve sheath tumors and meningiomas comprising 90% of all intradural/extramedullary tumors. Ependymomas and astrocytomas are the most common intramedullary neoplasms.

Meningiomas are the second most common intradural extramedullary neoplasm, second to nerve sheath tumors. Spinal meningiomas represent 12% of all meningiomas and 25% to 46% of primary spinal neoplasms. The annual incidence of primary intraspinal neoplasms is about five per one million in females and three per one million in males. Spinal meningiomas can affect people of all ages; however, they are most prevalent between the fifth and seventh decades of life. Seventy percent of spinal meningiomas are found in females. In women, spinal meningiomas are found with the highest frequency in the posterior, posterolateral (most common), or lateral thoracic region (80%), anterior cervical region (15%), and lumbosacral region (5%). In men, the distribution of spinal meningiomas is 50% thoracic and 40% cervical. Cervical meningiomas can be particularly problematic because they can adhere to the vertebral artery near its intradural entry and proximal intracranial course.

Embryologically, meningiomas arise from persistent arachnoid cap cells and not from the dura. The arachnoid cap cells form the outer layer of the arachnoid mater and villi. The most common histopathologic subtypes are psammomatous, meningothelial, fibrous, and transitional. The psammomatous subtype is the most common histology of spinal meningioma, followed by meningothelial and transitional. The psammomatous type contains numerous deposits of calcium. The etiology of meningiomas is uncertain; however, there are associations with exposure to ionizing radiation, hormonal influences, chemical exposure (lead), viral infection, and family history.

Spinal meningiomas are usually benign, slow-growing tumors with lateral expansion into the subarachnoid space. Patients often have a long clinical history prior to diagnosis because of the slow growth of the tumor. The mean duration of symptoms reported in the literature ranges from 12 to 24 months. However, given the smaller space in the spinal canal, meningiomas can cause neurologic symptoms when they are quite small as opposed to intracranial meningiomas. Spinal meningiomas are typically well-circumscribed lesions that do not invade into normal tissue and generally do not seed other locations. They are usually solitary; however, when multiple, raise the suspicion of neurofibromatosis type II. The incidence of multiple spinal meningiomas is 1% to 2%. Malignant degeneration of a spinal meningioma is rare.

Focal pain is the most common manifesting symptom in patients with spinal meningiomas. Radiating pain is less commonly seen. The pain is typically constant and described as burning or aching in quality. Loss of strength, paresthesias, gait abnormalities, and bowel and bladder dysfunction can occur, although less frequently. Although slow growing, spinal meningiomas can lead to chronic compressive myelopathy leading to spinal cord ischemia, either from direct compression or from alteration in blood supply. This can lead to permanent neurologic deficit even after successful surgery.

Imaging Features

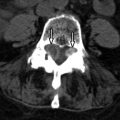

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice. The mass is readily identified, as well as its location and proximity to the spinal cord, other nervous tissue, and vasculature. The typical meningioma demonstrates iso- to hypointensity to the spinal cord on T1-weighted images and iso- to slight hyperintensity on T2-weighted acquisitions ( Fig. 47-2 ) . Calcifications in the mass are identified as regions of T1- and T2-weighted hypointensity ( Fig. 47-3 ) . Aside from regions of calcification, there is robust, homogeneous enhancement of meningiomas (see Fig. 47-2 ). One may see enhancement of the adjacent dura (“dural tail”), which is commonly seen as with intracranial meningiomas but is similarly not specific for meningioma. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrates spinal meningiomas as an iso- to mildly hyperdense mass with homogeneous enhancement. Calcification can be readily identified on noncontrast CT as focal regions of hyperdensity ( Fig. 47-4 ) . Myelography does not identify the mass but demonstrates the effect of the mass on the dural sac and spinal cord. When viewed in a plane parallel to the mass and spinal cord, an intradural extramedullary mass will appear as a negative defect in the spinal column with widening of the contrast-filled space immediately cephalad and caudad to the mass, between the dural sac and the negative defect from the spinal cord ( Fig. 47-5 ) . The addition of CT to myelography gives only marginally more benefit than CT alone ( Fig. 47-6 ) .