The knee has unique anatomy regarding the relationship between the synovial and capsular layers, with interposed fat pads at certain locations. The extrasynovial impingement and inflammation syndromes about the knee are underdiagnosed and should be included in the differential diagnosis of anterior knee pain. MR imaging is the best imaging modality for evaluation of the anatomy and disorders of these extrasynovial compartments.

Key points

- •

The knee has unique anatomy regarding the relationship between the synovial and capsular layers, with interposed fat pads at certain locations.

- •

The extrasynovial impingement and inflammation syndromes about the knee are underdiagnosed and should be included in the differential diagnosis of anterior knee pain.

- •

MR imaging is the best imaging modality for evaluation of the anatomy and disorders of these extrasynovial compartments.

Introduction

The knee demonstrates unique anatomy with regard to the capsular-synovial relationship and in particular contains several interposed fat pads. The 3 intracapsular fat pads are present within the anterior portion of the knee and include the infrapatellar (Hoffa) fat pad, the anterior suprapatellar (quadriceps) fat pad, and the posterior suprapatellar or prefemoral fat pad (PFP). In 1953, MacConaill proposed that fat pads not only occupy dead space in the joint but also help maintain the joint cavity and promote efficient lubrication by helping to distribute synovial fluid. This theory may explain the presence of fat pads in areas of the body exposed to mechanical stresses, such as the knee.

The capsule of the knee is a complex structure with up to 3 different layers. The most internal layer is located just superficial and parallel to the synovial membrane for most of its course. The capsule at the anterior portion of the knee is thinner compared with the capsule at the posterior portion of the knee and the extensor mechanism serves as its anterior and outer margin. At the inferior aspect of the extensor mechanism, the proximal part of patellar tendon partially replaces the capsule, composed of only a thin expansion attached to the patellar margins and patellar tendon. The boundaries of the synovial membrane are more familiar to radiologists and orthopedic surgeons because they are outlined by joint distention during arthrography and arthroscopic surgery. The extrasynovial cruciate ligaments are incompletely surrounded by synovium, however, with the region posterior to the posterior cruciate ligament devoid of synovium.

Understanding the unique anatomy of the knee is essential toward the goal of understanding extrasynovial disorders and impingement syndromes ( Fig. 1 ). Anterior knee disease includes many conditions whose nosologic framework is still not fully standardized. Extrasynovial inflammation and impingement syndromes about the knee are certainly underdiagnosed and should be in the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with anterior knee pain. This article reviews the inflammation and impingement syndromes affecting the superior fat pad, inferior fat pad, pericruciate fat pad, and PFP in the knee, including Hoffa disease, iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome, and adhesive capsulitis (AC).

Introduction

The knee demonstrates unique anatomy with regard to the capsular-synovial relationship and in particular contains several interposed fat pads. The 3 intracapsular fat pads are present within the anterior portion of the knee and include the infrapatellar (Hoffa) fat pad, the anterior suprapatellar (quadriceps) fat pad, and the posterior suprapatellar or prefemoral fat pad (PFP). In 1953, MacConaill proposed that fat pads not only occupy dead space in the joint but also help maintain the joint cavity and promote efficient lubrication by helping to distribute synovial fluid. This theory may explain the presence of fat pads in areas of the body exposed to mechanical stresses, such as the knee.

The capsule of the knee is a complex structure with up to 3 different layers. The most internal layer is located just superficial and parallel to the synovial membrane for most of its course. The capsule at the anterior portion of the knee is thinner compared with the capsule at the posterior portion of the knee and the extensor mechanism serves as its anterior and outer margin. At the inferior aspect of the extensor mechanism, the proximal part of patellar tendon partially replaces the capsule, composed of only a thin expansion attached to the patellar margins and patellar tendon. The boundaries of the synovial membrane are more familiar to radiologists and orthopedic surgeons because they are outlined by joint distention during arthrography and arthroscopic surgery. The extrasynovial cruciate ligaments are incompletely surrounded by synovium, however, with the region posterior to the posterior cruciate ligament devoid of synovium.

Understanding the unique anatomy of the knee is essential toward the goal of understanding extrasynovial disorders and impingement syndromes ( Fig. 1 ). Anterior knee disease includes many conditions whose nosologic framework is still not fully standardized. Extrasynovial inflammation and impingement syndromes about the knee are certainly underdiagnosed and should be in the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with anterior knee pain. This article reviews the inflammation and impingement syndromes affecting the superior fat pad, inferior fat pad, pericruciate fat pad, and PFP in the knee, including Hoffa disease, iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome, and adhesive capsulitis (AC).

Hoffa disease

Introduction

The infrapatellar fat pad (IFP), or Hoffa fat pad, composed of large conglomerates of adipose tissue with a surrounding net of fibrous connective tissue and vascularization, is the site of Hoffa disease.

First described in 1904, acute or repetitive trauma to the fat pad causes internal hemorrhage leading to an inflammatory cascade with edema and hypertrophy of the fat pad. This morphologic change in the fat pad results in mechanical impingement between the femur and the tibia. A vicious cycle of inflammation and pain ensues with subsequent deposition of fibrin and hemosiderin, with fibrous tissue, leukocytes, perivascular cells, and fibrin-occluded blood vessels seen on histologic examination. At the end stage of disease, scarring, fibrosis, and calcification may occur. Ogilvie-Harris and Giddens found Hoffa disease present in 1% of patients undergoing knee arthroscopy, suggesting that this entity may be underdiagnosed by imaging.

Several mechanical abnormalities can occur in the IFP, including acute injury or microtrauma due to blunt impact, shear injury with anterior cruciate ligament tearing, patellar dislocation, torsion, or impingement, each showing different MR imaging patterns.

Similar imaging findings have been reported in patients with HIV ( Fig. 2 ), characterized by global homogeneous increase in signal intensity throughout the IFP on fluid-sensitive sequences. In this subset of patients, the quadriceps and PFPs may also be involved and show signal alteration. Structures adjacent to the IFP can be affected by synovial processes and mimic symptoms of IFP impingement. The deep infrapatellar bursa is located immediately posterior to the distal portion of the patellar tendon and can be affected by inflammatory bursitis with or without an associated Hoffitis or other disorders.

Clinical

Clinical features consist of pain around the patellar tendon, close to the femorotibial joint line with loss of normal hyperextension. Hoffa reported that affected patients feel pain when pressure was applied to both sides of the patellar tendon during passive extension of the knee.

Most IFP pathologies are successfully managed with the combination of antiinflammatory drugs, physical therapy, taping, muscle training, gait training, and injections of local anesthetic and corticosteroids to decrease pain and inflammation. For patients who fail conservative therapy, arthroscopic resection of the impinging fat pad produces sustained relief of symptoms with low rates of morbidity and complications.

Imaging

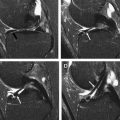

Sagittal and axial images on T1-weighted and T2-weighted fat-suppressed sequences provide optimal evaluation of the IFP. The acute phase of the disease demonstrates high T2 and low T1 signal in the IFP ( Fig. 3 ). The IFP may be enlarged with accompanying mass effect on the patellar tendon. Enhancement may be present in the fat pad after intravenous gadolinium administration. Chronic cases can demonstrate fibrosis, hemorrhagic deposition, and rarely calcification, characterized by hypointense signal on T1- and T2-weighted images.

Deep infrapatellar bursitis is another cause of anterior knee pain and has a different pathophysiology from Hoffa disease but may result in reactive changes in the IFP given its contiguity with the anterior surface of the fat pad. The imaging findings include a focal collection of high signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences confined between the distal portion of the patellar tendon and the anterior aspect of the IFP. The adjacent fat pad can show signs of inflammation with signal abnormality ( Fig. 4 ).

Patellofemoral friction syndrome

Introduction

Patellofemoral pain and patellar instability are the 2 main symptoms in patellofemoral disease that includes many conditions.

The Lyon School of Knee Surgery classified patellofemoral disease into 3 distinct entities :

- 1.

Objective patellar instability (OPI), which is defined by the presence of at least 1 episode of true patellar dislocation or radiologic sequelae and at least 1 anatomic abnormality confirmed by imaging: trochlear dysplasia, patella alta, patellar tilt, or tibial tuberosity (TT)–trochlear groove (TG) distance abnormality

- 2.

Potential patellar instability (PPI), which is characterized by the presence of subjective patellar pain and/or instability (reflex) with no history of true patellar dislocation and the same anatomic abnormalities as in OPI

- 3.

Patellar pain syndrome (PPS) without a major morphologic abnormality on radiographs.

The symptoms include a combination of patellar pain, reflex buckling, and occasional pseudolocking. The 2 first topics (OPI and PPI) are necessarily related with anatomic abnormalities. Patients presenting with anterior knee pain in the infrapatellar region related to a friction syndrome often fall into the spectrum of PPS but eventually can also have patellofemoral malalignment and fall into the spectrum of PPI or OPI.

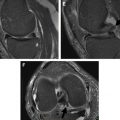

Brukner and colleagues first used the term, infrapatellar fat pad impingement , in 1999 and Chung and colleagues introduced the term, patellofemoral friction syndrome , in a study of 42 patients. These patients with chronic anterior and lateral knee pain showed edema within the anterolateral fat of the anterior compartment of the knee ( Fig. 5 ). The edema described may be the result of impingement between the lateral femoral condyle and the posterior aspect of the patellar tendon.

The IFP contains adipocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, and granulocytes as well as nociceptive nerve fibers that could in part be responsible for anterior pain. It plays a role in stabilizing the patella in extremes of flexion and extension.

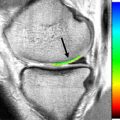

Clinical

Clinically, the patellafemoral friction syndrome is characterized by anterior pain and tenderness, typically at the lower lateral pole of the patella. This is more common in young patients who engage in routine physical activities. Similar to a majority of other fat pad impingement syndromes, this friction syndrome occurs with flexion, extension, and mechanical maltracking of the patella. These movements result in remodeling of the morphology of the fat pad, adjusting its shape to the space between the joint ( Fig. 6 ). Knee pain can be exacerbated by hyperextension, and physical examination can demonstrate focal point tenderness at the inferior pole of the patella. IFP pathology, including friction syndrome, is usually successfully managed with conservative therapy, including physical therapy targeted at restoring the biomechanics of patellar tracking and taping with the attempt to unload the inferior fat pad.

Imaging

Sagittal and axial imaging planes best demonstrate the patellar tendon and its relationship with the lateral femoral condyle.

Focal increased signal intensity on fluid-sensitive MR images of the superolateral portion of the IFP between the patellar tendon and the lateral femoral condyle has been described as edema related to the friction syndrome ( Fig. 7 ). Enhancement can be seen after intravenous contrast administration.

Anatomic abnormalities of the extensor mechanism, including patellofemoral malalignment, may be related to patellar tendon lateral femoral condyle friction syndrome. Patella alta and an increased TT-TG distance are 2 associated findings observed in patients with edema of the superolateral portion of the IFP.

Values for patella alta and patella baja were described for radiographs; however, minor adjustments for CT and MR imaging show excellent reproducibility for the 3 classic methods described. The Insall-Salvati (ISI) index uses the ratio of patellar tendon length divided by patellar length (TL/PL). Prior investigators have defined patella alta as TL/PL greater than 1.2 and patella baja as TL/PL less than 0.8. The modified ISI ratio is based on the distance between the distal end of the articular surface of the patella and the patellar tendon insertion on the tibia (PT) and the length of the articular surface of the patella (P). The original publication only defined the patela alta value with a PT/P ratio greater than 2. The Caton-Deschamps method measures the distance between the distal point of the patellar articular surface and the anterior-superior border of the tibia divided by P. The values determined by Caton were greater than or equal to 1.2 and less than or equal to 0.6 for patella alta and patella baja, respectively.

The TT-TG distance was first described for CT but has been shown to be reproducible for MR imaging. Measurements are made on axial images. The TG point represents the deepest cartilaginous point of the most superior image that depicts the complete cartilaginous trochlea. The TT point represents the center of the patellar tendon insertion onto the TT. To obtain the TT-TG measurement, a tangent line to the cartilaginous border of the posterior condyles is drawn with a perpendicular line to the previously determined TG point. These 2 lines are transferred to the level of the TT point, where a perpendicular line is also drawn to the epicondylar tangent. The distance between the TG line and the TT line is the TT-TG value. Pandit and colleagues suggested a value of 10 ± 1 mm in the normal control group, using the MR imaging technique. In one of the most cited articles regarding TT-TG, using CT, Dejour and colleagues found that the TT-TG was 12.7 ± 3.4 mm in their control group and that a value of greater than 20 mm was pathologic.

Patella alta may allow the patellar tendon to lie in front of the lateral trochlear facet. The increased TT-TG distance in patients with edema of the superolateral IFP could lead to a lateral displacement of the patellar tendon such that it is opposed to the lateral femoral condyle, facilitating an impingement between these 2 structures. A reduced distance of the patellar ligament to the lateral trochlear facet is directly related to the presence of edema at the lateral portion of the IPFP. Patellar tendon abnormalities are also associated with this friction syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree