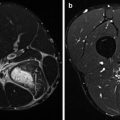

Fig. 43.1

(a) ‘Demi pointe’, (b) ‘en pointe’, (c) ‘turnout’, (d) ‘fifth position’

Treatment consists of ice application, anti-inflammatory medication in the acute phase, physical therapy and limiting ‘turnout’ (Fig. 43.1) and working ‘en pointe’ during the recovery period. Furthermore, the dance technique should be improved, especially the ‘jumps’ and ‘turnout’. During physical therapy, ice massaging, stretching and strengthening of the FHL tendon could be beneficial. Insoles can be effective in the dancer who has a naturally pronated foot. A steroid injection can be given, but weakness and rupture of the tendon may occur. Relapse after corticoid infiltrations is common (Hamilton et al. 1996). Explorative surgery and a release of the tendon sheath may be required if conservative treatment fails (Sammarco and Cooper 1998).

The most common fracture among dancers is the dancer’s fracture. This is a spiral fracture of the shaft of the distal fifth metatarsal. It usually occurs secondary to an inversion sprain from the ‘demi-pointe’ position where a maximal dorsiflexion of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) and an ankle plantarflexion is required (Garrick and Lewis 2001). The dancer will complain of immediate pain and swelling. A radiograph confirms the diagnosis. In displaced or malrotated fractures, surgery is indicated and in other cases management consists of immobilization of the fracture. During 4–6 weeks, a rocker-bottom shoe is essential, followed by 4–6 weeks of rehabilitation. The physical therapy consists of proprioception training, strengthening exercises and mobilization of the ankle.

Because of repetitive movements, dancers are vulnerable to stress reactions and stress fractures. The second metatarsal is the most common site for occurrence of stress fractures in dancers (Garrick and Lewis 2001). The onset is often insidious and gradually worsens until dancing is almost impossible. Risk factors specific to ballet are a faulty dance technique, gender (female > male), irregular or absent menses and malnutrition. Early diagnosis with a bone scan or MRI is possible before radiographs demonstrate the problem. Treatment is the same as in the general population.

Hallux valgus is a deviation of the great toe towards the lateral side of the foot. This is frequently seen in dancers as a result of forcing ‘turning out’, where excessive pronation increases valgus stress of the hallux (Quirk 1994). In early phases it is often asymptomatic, but when a deformity develops, pain and restriction of movement of the first MTP joint may occur. Radiographs reveal the severity of the pathology. Bony exostoses and a bursitis develop around the first MTP joint. Bunion means an area of swelling and refers to the prominent medial portion of the first metatarsal head. This can be the bursa or osteophyte. Footwear to reduce friction over the bunion is necessary. Correction of the valgus position of the first MTP joint by surgery is the final option of treatment.

Hallux rigidus is a term for restricted mobility of the big toe due to exostoses or osteoarthritis of the MTP joint. Symptoms are pain and restriction of dorsiflexion during demi pointe (Fig. 43.1). In an early stage, it is called hallux limitus and in young dancers the term juvenile hallux rigidus is used. It is more frequently seen in female dancers. The degree of degeneration is shown on radiographs. Initial treatment involves relative rest, NSAIDs, cortisone injection, physiotherapy and a correction of biomechanical factors with insoles. Arthrodesis is not performed in this population because surgical fixation of the MTP joint will end their career. If conservative treatment fails, cheilectomy (Roukis 2010; Wagenmann et al. 2011; Rietveld and van de Wiel 2011) or arthroplasty of the first MTP joint can be required.

Morton’s interdigital neuroma is usually located between the third and fourth metatarsals (third web space). It is a swelling of the nerve and scar tissue and can be palpable in some cases (Kennedy and Baxter 2008). During compression typical pain radiating into the toes with paresthesia will be noted. Ultrasound may confirm the diagnosis. Ice application in acute phases, insoles to spread the load over the metatarsals and intrinsic foot muscle strengthening exercises are all part of the initial treatment. A corticosteroid injection can be given and in chronic cases surgical excision is indicated. Ultrasound-guided alcoholization is recently developed as an alternative to surgery.

Pain and tenderness in the metatarsal region is called metatarsalgia. If the second metatarsal is longer than the first, metatarsalgia is more frequent (Rietveld and van de Wiel 2011). In the ideal dance, foot metatarsal one and two are of equal length. Custom-made insoles in ballet shoes are a good solution and if this fails an osteotomy of the second metatarsal may be indicated.

The plantar fascia or the thick connective tissue which supports the arch of the foot. The inflammation tendinopathy of the plantar fascia (PF) is mostly due to repetitive microtrauma. Improper footwear, plantar fascia laxity or tightness, excessive pronation of the foot, pes planus and pes cavus are also risk factors. Plantar fasciitis (fasciopathy) gives pain at the medial calcaneal tuberosity and is aggravated with the toes dorsiflexed to tighten the PF (Woolnough 1954). Ultrasound confirms the diagnosis. Radiographs may show a calcaneal spur that is not related to the fasciitis, this in contradistinction with common thoughts. Pathology resembles that of tendinosis and it is also treated this way. Dancers may dance ‘en pointe’ (Fig. 43.1) but must avoid the ‘demi-pointe’ (Fig. 43.1) position.

Sesamoids are isolated intratendinous bones. In general, there are two sesamoids at the first MTP joint located in the flexor hallucis brevis tendon under the first metatarsal head. During ‘en pointe’, stress increases on the sesamoids. Injuries usually occur at the medial sesamoid.

Numerous pathological processes can occur: (stress) fracture, osteoarthritis, osteochondritis, sprain of a sesamoid, sprain of the sesamoid-metatarsal articulation, tendinopathy of the flexor hallucis brevis and ganglion cyst between the sesamoids (Mellado et al. 2003). Clinical features are pain during forefoot weight bearing and tenderness and swelling at the sesamoid. Testing the functional range of motion of the first MTP joint is usually painful and often restricted. Radiographs may rule out a fracture. However, radiographs in a stress fracture can be negative for several weeks and an isotopic bone scan or MRI is needed to clarify the diagnosis. Without treatment sesamoid problems can lead to chronic pain and disability. The initial treatment of sesamoid inflammation involves rest, ice, compression and elevation (RICE), NSAIDs and avoidance of flexion of the MTP joint as well as contraction of the flexor hallucis brevis. A sesamoid pad (padding) can distribute weight away from the sesamoid bones, and insoles are required if foot mechanics are abnormal. Corticosteroid injections may be effective. Sesamoid stress fractures are treated with 6 weeks of non-weight-bearing and are prone to non-union. Sesamoid problems should be treated non-surgically, as sesamoidectomy can create imbalance especially during ‘en pointe’ and may cause a hallux abducto valgus deformity. Rehabilitation can take a long time and gradual increase in weight bearing after resolving of symptoms is necessary.

43.1.3 Injuries of the Ankle

Common overuse injuries of the ankle are a posterior and anterior impingement syndrome. Posterior impingement syndrome is also known as dancer’s heel. During movement of ‘demi pointe’ or ‘en pointe’, the dancers note pain at the posterior ankle. In full ankle plantarflexion, there is compression between the posterior tibia and posterior talus. On radiographs an enlarged posterior tubercle of the talus or an os trigonum may be present (Moser 2011; Russell et al. 2010).

Athletes with anterior impingement syndrome usually have pain at the anterior side of the ankle during movements of dorsiflexion such as ‘plié’. This is most often seen in dancers with pes cavus and an anteromedial osteophyte or in dancers with an exostose secondary to a traction injury of the joint capsule of the ankle. This injury occurs whenever the foot is repeatedly forced into extreme plantarflexion. Radiographs may show exostoses and abnormal tibiotalar contact.

If further information is required, an MRI (or bone scan) may be useful in both cases. Early management with physical therapy, relative rest and NSAIDs can be very useful. A corticoid infiltration can be given when improvement is insufficient. In anterior impingement syndrome, a heel lift to minimize the impingement can also be helpful. Surgery may be necessary if conservative treatment fails and this can be performed arthroscopically or by an open procedure.

Ankle sprains and especially sprains of the lateral ligaments are frequently seen in dancers. The anterior talofibular ligament is most commonly involved. Diagnosis and treatment are similar to those of the general population. Immediate care should include RICE. A radiograph to exclude a fracture should be done. Most of the time, sprains can be treated symptomatically with an ankle brace followed by rehabilitation involving physiotherapy during 4–6 weeks. In recurrence of ankle sprains and ankle instability, formerly radiographs in valgus and varus stress were indicated; these are now replaced by ultrasound or MRI. In chronic ankle instability, surgical stabilization could be necessary.

Achilles tendinopathy is a common injury among the general population and dancers alike. Posterior tendon irritation is secondary to the repetitive dorsiflexion and plantar flexion motions. ‘Demi pointe’ (Fig. 43.1a) places more stress on the Achilles tendon than ‘en pointe’ (Fig. 43.1b). Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment are the same as in other patients.

43.1.4 Injuries of the Lower Leg and Knee

Stress fractures of the tibia can be located at the posteromedial side of the tibia or at the anterior edge of the tibia. The last one is more resistant to treatment and is more at risk to develop non-union. The focal pain gradually increases and is provoked by movements. With palpation there is tenderness along the tibia. Bone scan or MRI is the golden standard to establish the diagnosis.

Treatment is equivalent to the ‘ordinary’ patient. It is necessary to identify which factors precipitated the stress fracture.

Periostitis, medial tibial stress syndrome or medial tibial traction periostitis gives diffuse pain at the medial border of the tibia. Dancing is possible, but pain gradually increases after dance and is worse the following morning. Radiographs are routinely negative and an isotopic bone scan may show diffuse areas of increased uptake along the cortical bone of the tibia. This is in contrast to stress fractures, which should show focal uptake. Treatment is based on symptom relief, identification of risk factors and treating the underlying pathology.

Patellofemoral pain is the preferred term used to describe pain in and around the patella. Knee problems are most often caused by patellar problems (>50 %). Overuse, abnormal Q-angle, laxity, increased range of motion of the knee and neighbouring joints (Steinberg et al. 2012), poor technique and variations in anatomic alignment of the lower extremities can give patellar problems in dancers. Dancers with excessive femoral anteversion can have compensatory faulty technique with the knee and the ankle when there is lack of turnout at the hip. Tight iliotibial bands (ITB) are also associated with patellofemoral pain in dancers (Winslow and Yoder 1995). The symptoms are diffuse anterior knee pain that is exacerbated by dance activities such as plié, knee bends, stairs or prolonged sitting (movie sign). Quadriceps or vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) hypotrophy gives the feeling of ‘giving way’. Weak external rotator muscles of the hip and quadriceps, tightness in the ITB and pronated feet may be found and have to be treated. Strengthening of VMO, stretching TFL and correcting a faulty technique are indicated. Taping or bracing can be associated. Radiographs are routinely negative and surgery is rarely needed.

Subluxating and dislocating patellae occurs more in adolescent dancers with shallow trochlear grooves, abnormal Q-angles, excessive ligamentous laxity, abnormal lateral patellar movements and hyperextended knees. Subluxation can occur without any damage. Severe acute pain and hydrops is due to patella dislocation. Extension of the knee along with the quadriceps muscles pulls the patella back into position. Treatment consists of RICE. Radiography to exclude a fracture is necessary; MRI can diagnose fracture fragments and a tear of the medial patellofemoral ligament or retinaculum. Knee immobilization for a few weeks is indicated. Rehabilitation consists of strengthening the vastus medialis obliquus, which is the key to patellar control (Pattyn et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2008). Stretching the lateral structures (mainly the ITB) should be added if tight lateral retinacular structures are present. Hamstring strengthening is recommended to prevent hyperextension. Wearing a brace during class is helpful but cannot be used during performance most of the time. In case of relapse, surgery to restore the medial patellofemoral ligament is indicated.

Patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee) is like other tendinopathies an overuse injury. Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment are in accordance with the classical protocol of tendinopathy.

Hyperextension of the knee or improper landing of a jump can cause ligament injury (MCL, LCL or ACL). In dance these injuries are not frequently seen; they more occur often during contact sports and unexpected movements. Dance movements are choreographed and therefore predictable. Symptoms, physical examination, diagnostics and treatment are the same as in the standard young and active population. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is recommended to stabilize the knee. Rehabilitation with strengthening the hamstrings and quadriceps and proprioceptive exercise to practice turning and changing direction are necessary before returning to dance.

Medial meniscal tears are caused by increased turnout; lateral meniscus is at risk during ‘plié’. In meniscus injuries symptoms, physical examination, diagnosis and treatment are according to a meniscal tear in the general population. If the knee locks or pain and effusion persist, arthroscopy is necessary. Quadriceps setting exercises are recommended to avoid atrophy. A faulty technique has to be corrected. Exercises to encourage the use of short hip external rotators for turnout and abdominal muscle strengthening and stretching of the hip flexors to control the pelvis are useful to decrease torsion of the knee.

43.1.5 Injuries of the Hip

M. piriformis is responsible for external rotation and flexion of the hip and stabilization of the pelvic girdle. Different piriformis conditions are seen in athletes, but the diagnosis remains controversial. Piriformis muscle strain gives deep buttock pain that is exacerbated by sitting, prolonged standing and movement that requires external rotation and abduction of the hip. Clinical factors are chronic muscle shortening, tenderness and reduction of passive internal hip rotation. In both cases conservative stretching and strengthening of the piriformis and surrounding muscle groups or trigger point injections can be helpful.

‘Snapping’ hip is seen in 91 % of the dancers and in 80 % on both sides (Winston et al. 2007). It is also named coxa saltans and is divided into external (lateral) and internal snapping hip. External snapping hip is due to the posterior iliotibial band or anterior edge of the gluteus maximus muscle sliding across the greater trochanter. Internal snapping hip is described as rubbing of the iliopsoas tendon over the anterior ridge on the femoral head, the iliopectineal ridge or a portion of the iliacus muscle belly; the latter is probably the most prominent cause (Wahl et al. 2004). The iliopsoas is the most frequently involved anatomical structure in snapping hip (Winston et al. 2007). Most of the time, this snapping is asymptomatic. If pain occurs bursitis or tendinopathy should be excluded. Physical examination can show local tenderness. Moving the flexed and internally rotated hip passively to an extension and externally rotated hip may provoke ‘snapping’. Ultrasonography is used to confirm the diagnosis and can show tendinosis or bursitis. Initial treatment consists of relative rest, NSAIDs for a short period, physiotherapy and attention to ballet technique. Peripelvic stretching and strengthening exercises particularly of the iliopsoas are indicated. Occasionally surgical release may be required.

43.1.6 Injuries of the Back

Due to repetitive or acute hyperextension of the spine dancers are at risk for back injury. The majority of back injuries in dancers involve the lumbar region.

Spondylolysis refers to a defect in the pars interarticularis of the vertebra without displacement of the vertebra. It is more common in the adolescent dancer and is due to repetitive extension of the lower back. The pain increases by lumbar hyperextension and the dancer notices pain with movements such as ‘cambré backwards’ (Fig. 43.2). The dancer will note lumbar spine stiffness, gradually worsening dull back pain that radiates into the buttock. Physical examination shows hyperlordosis and tightness of the hamstrings. Radiographs may confirm the diagnosis. Bone scan is more sensitive and indicated if radiographs are negative. The athlete with early-stage defects is best treated with a hard brace in the acute situation (Rietveld and van de Wiel 2011; Sairyo et al. 2012). Decreased activity and an anti-lordotic rehabilitation programme are necessary in acute and chronic conditions.

Fig. 43.2

‘Cambré backwards’

Spondylolisthesis is defined as the forward slippage of a vertebra in relationship to an adjacent vertebra and may be due to bilateral spondylolysis. Management is conservative and consists of lumbar bracing, avoiding lumbar hyperextension and physical therapy. Surgery could be necessary if there is severe pain, neurologic findings or in stage three (>50 %) and four (>75 %) spondylolisthesis.

Scoliosis is a sideways curvature of the spine. Scoliosis is significantly more common in dancers than in the general population. During physical examination children bend forward to 90° at the hips with the knees straight. An asymmetric prominence of one side of the thoracic or lumbar region compared to the other side is an early sign of scoliosis. Other signs such as asymmetry of shoulder height or scapular prominence, unequal arm height and waistline or lower limb length can be noted. Radiographs of the spine have to be taken to assess the severity of the curve and for follow-up. In most cases specific treatment is unnecessary but observation until completion of growth is required. A well-balanced scoliosis, even if large, does not necessarily exclude a successful dancing career.

Facet joint osteoarthritis is seen in the older dancers. Repetitive lumbar hyperextension (Fig. 43.3) causes stress on the facet joints and may result in degenerative changes. This progress occurs over years, but the symptoms can appear in a relatively short period of time. Radiographs shows facet joint osteoarthritis and a bone scan may show an area of increased activity.

Fig. 43.3

Lumbar hyperextension causes stress on the facet joints. Injuries of the upper limbs occur more often in male dancers

Relative rest, anti-inflammatory drugs and most importantly anti-lordotic exercises are the treatment of choice. Facet infiltration or facet denervation can decrease the pain. Rarely, surgery may be considered if non-operative treatment fails.

Disc herniation is more often seen in male dancers because of lifting the partner (Fig. 43.4). Lifting with hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine and a poor lifting technique with outstretched arms away from the body may increase herniation risk. Symptoms, clinical research, diagnosis and treatment are similar as in the general population.

Fig. 43.4

Lifting technique is important to avoid injuries

43.1.7 Injuries of the Upper Back, Neck and Shoulder

Injuries to the bone and discs at the upper back and neck are unusual. Most of the time, it consists of muscle strains, tendinopathy or ligament sprains. They may occur during lifting as a result of muscle weakness or being off balance. These problems are more common in male than in female dancers (Figs. 43.3 and 43.4).

43.1.8 Conclusion

Musculoskeletal injuries are frequently seen in dancing, especially overuse injuries of the lower extremity. Older age, fatigue, higher intensity and frequency of training, menstrual dysfunction and psychological factors like stress and anxiety make the dancer prone to injury.

Specific injuries occur due to dancing and treatment differs from the general population. Taking a mandatory break for recovery or treatment is frustrating for many dancers and this ‘taboo’ is often enhanced by the expectations of the entourage. Finding alternative methods to keep an injured dancer active and preventing deconditioning are important. Taping and bracing are most of the time not possible during performance, not only because of the fact that full range of motion is mandatory but also because of aesthetics. Prevention is the key to decrease the incidence of injuries (Ojofeitimi and Bronner 2011). Stabilization exercises, neuromuscular control training, improving technique, a healthy diet, proper footwear, aerobic training and respecting physiologic and psychological limits play an important role in this prevention (Kiefer et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2012; Zulawa and Pilch 2012; Pearson and Whitaker 2012).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree